Nobody has ever made an album like this.

By which I do not mean, nobody other than Joni Mitchell, although that is also true. Rather that, between the times I listen to it, it ceases to be what it is when I play it – as if it were one of those quantum particles whose state is defined only when observed. I can never remember exactly what it’s like, between those plays. I have a sense of it. I think I know it. But I hear it again and realise I don’t, until it’s in the room with me.

In that, and many other ways, it’s qualitatively different from the folk-pop records which made Mitchell’s name. Most of those are brilliant, so far the best thing of their kind that it is apt they are also the progenitors of most things of their kind. Their shape is clear and their substance certain. Like figurative art, which is what they are, they are still there when you turn away. It is on this album that Mitchell becomes truly and sublimely elusive – a kind of protean fire sprite flickering like hungry light through her own music. Nobody has ever made an album like this; although plenty must have tried and no doubt some of them have done remarkable yet different things in the attempt.

It doesn’t really matter whether The Hissing Of Summer Lawns is Mitchell’s best album. What does matter is that anyone who thrills to, say, Blue, as well they might, may find this even more thrilling if they’ve yet to hear it. Mitchell is unusual among major artists in that little of her very finest work is among her most famous, with the possible exception of this album’s predecessor, Court And Spark. Hejira, the magnificent record that followed it, is stranger, more exotic, more thickly draped in mysteries. There are those – I’ve met one or two – who most adore Mingus, her daring 1979 collaboration with the great double bassist. Then again, “daring” is tautological when cited in tandem with Joni Mitchell, whose career is one of unparalleled audacity. People think Bowie, or Prince, were daring. People are right. But Mitchell risked everything, and lost much of it, and a fuck she did not give. No great star has ever been so fearless in the face of their waning stardom. There’s no Let’s Dance in her catalogue, no Batman soundtrack. (Nothing wrong with those records, either; the point is only they were constructed with at least one eye on the main chance.) In pop, history is written not by the winners, but about them. If history had it right, history would put the Joni Mitchell of the mid-to-late 70s not merely close to the pinnacle, where her earlier folkie incarnation resides, but right atop it with the very best of them.

Everything Mitchell did between 1974 and 1979 is sui generis other than within her own catalogue; certainly so in the wider pop canon. The common thread to it is jazz, and I am unsure what to make of the fact Mitchell is regarded in retrospect not as a jazz artist, despite her greatest music drawing upon it heavily, but almost invariably as a folk artist. I see three possible explanations. One is that so original was her use of jazz in the singer-songwriter mode, she wasn’t recognised principally as an exponent of the form (rather as, say, Massive Attack weren’t acknowledged as a rap band.) The second: simply, because her “hits” are found almost entirely among her earlier, folkier songs. The third: so limited are the roles for women in jazz – vocalist, and that’s usually it; the exceptions are just that: exceptional – that the notion of a female auteur redefining its possibilities just doesn’t compute. I suspect there’s some truth to all three. (I wrote about this particular question at greater length here for Intelligent Life.)

When I do play The Hissing Of Summer Lawns – I had it on just now, as you’d expect, but I switched it off to write because I can no more hear it and find words of my own than I can taste chicory through a double espresso – I am, ever and again, softly dazzled by its very existence. If I’d never heard another Joni Mitchell record, I’d find it remarkable enough as a piece in itself. In the context of her oeuvre, it’s less an astonishing leap, more a dizzy ascent along the same path that Court And Spark had set her upon. It was on that album that she began her transformation from diarist/memoirist (the part her acolytes always found easiest to copy, although few would ever attain anything close to her insight and lucidity) to a composer of imaginative short fiction or portraiture in song. On The Hissing Of Summer Lawns she perfected it. Whatever callowness had lingered in her from those deceptive days as a wide-eyed hippie ingenue – one always gifted with hawk-like observation and glowing talent – was gone. No longer were her peers navel-gazing strummers of guitars. (Mitchell somehow saw the human soul in that navel, where many of her contemporaries found fluff.) They were the first rank of musicians, novelists, film-makers, and visual artists (among whose number she also belonged) who were taking their scalpels to a wearied America.

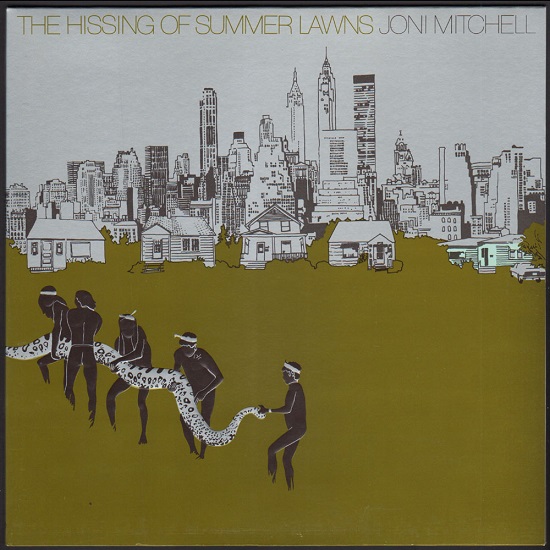

That’s her picture on the cover; a foreshortened coast-to-coast landscape in which the New York skyline looms behind the Beverley Hills suburbs where Mitchell herself lived – her house is on the right – while in the verdant foreground naked tribesmen carry a trapped giant snake. Hissing, lawns… geddit? It took me a while. As in, years. It looks to me now like a depiction of America’s id; the manifest portrayal of everything primal that hovers half-glimpsed behind the (also hissing) sprinklers – and of the way the civilised life of its moment curtailed all that had wildness in it. What David Lynch would later render as extravagantly gothic, Mitchell picked out with a truer sense of its peril. The fiends are not violence, depravity and abuse; they are ennui, banality, claustrophobia, despondency, the erosion of joy and beauty – and their quarry is female. Women in song who for once are not merely the objects or proponents of ardour. Although “merely” is the wrong word. Love is pop music’s great subject; but it need not be pop music’s only subject. The newness of what Mitchell did is underscored by the thought that it would be unusual even 45 years on.

But first, there is the joy and beauty of ‘In France They Kiss On Main Street’. Which is not about France, but about Main Street, Everyville. France is a dream, an ideal: Liberté, vivacité, électricité. ‘In France They Kiss On Main Street’ is an overture of sorts, an exuberant affirmation of everything in life and youth that stands to be lost in time and boondocks mundanity: “Under neon signs/A girl was in bloom/And a woman was fading/In a suburban room.” Right there is a precis of the album to follow, which will radiate out from that centre in iridescent waves. Rock & roll is the battle hymn in a “War of Independence” a fight waged by the young against those forces that determine their destiny is to fade in the suburbs, against elders who have “been broken in churches and schools/And molded to middle-class circumstances.” It is hard not to quote the entire lyric, so sweetly and exultantly does it conduct those livewire moments when everything crackles with possibility. The song itself echoes its own refrain, rolling, rolling, rock n’ rolling from its first rousing strum to its final tiny whoop. It is the calling card of fulfilled genius.

‘In France They Kiss On Main Street’ stands as a stepping stone between what Mitchell had been and what she was about to become. It would not have been notably out of place on Court And Spark. But ‘The Jungle Line’, with its thudding tribal drums and beat poetry incantations, certainly would. Now, there are, let’s say, issues with Mitchell and race. Not just the sleeve of Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter (1977), which one might generously explain away as theatricality in art, but her subsequent, jaw-dropping remarks about it. And to invoke the jungle, and Rousseau – whether he of the noble savages, or he of the Primitivist art; it proves to be the latter – on “Safaris to the heart of all that Jazz” in Harlem is, in today’s wince-inducing word, problematic. And yet. So evocative is its sorcery, so piercing of history’s sweep the lyric, that if one cares to justify it, one could say it is descriptive of the products of an attitude rather than an example of that attitude. And if one doesn’t, one may simply acknowledge both its uncomfortable stereotyping and its singular redolence and atmosphere, and accept that chipping away at the clay feet of great art for the purpose of bringing it down altogether is a kind of spiritual vandalism – as if the entire past must be slung out for failing to come up to code in the present.

The safari seems a preliminary excursion, but it isn’t. It travels by an unexpected route to the same set of views, which is female life seen both from the inside and the exterior. ‘The Jungle Line’’s barmaid is sister under the skin to Edith, she of the languid, lovely ‘Edith And The Kingpin’. The Kingpin is a small-time Mr Big, a local potentate, who has fixed upon Edith as his bedmate, the latest in a line of women who “grow old too soon”, raddled by cocaine and the terrors of their incumbency. Chosen, Edith has no choice. Taken, she must take what she is given. She is woman as vassal, no more free in her American town than her equivalent falling under the eye of a feudal village’s liege lord. No more free than the lavishly kept wife in the title track – who might be Edith, years on, prisoner of the man she’s captured – pacing the barbed wire perimeter of her ranch house like the caged animal she is. Or is she? Is it that liberty is impossible, or that she imprisons herself? “He gave her his darkness to regret/And good reason to quit him… Still she stays with a love of some kind/It’s the lady’s choice."

Here she is again, or again, her subcutaneous sister, in ‘Harry’s House – Centerpiece’, yet another of the post-Impressionist wonders Mitchell daubs onto the album in loose brushstrokes that coalesce with magical precision into perfect pictures; and every last one of those pictures has its shadows and it has some source of light. Here is Mad Men, three decades early. Harry in the city, surrounded by glamour and sexual opportunity; wifey in the suburbs, surrounded by dead air. And with astounding artfulness, Mitchell places at the heart of her own song a cover version, the swing-jazz standard, ‘Centerpiece’, in which the singer’s “pretty baby” is lauded as, quite literally, a piece of furniture around which his household is to be assembled. In the gap between 1958, the year of the song’s composition, when its subject was evidently intended to feel delight at such a prospect, and 1975, Mitchell unpicks how it feels to become a trophy. Edith, Harry’s wife, the “lady” of the summer lawn: all are prized possessions who learn the hard way just what it is to be acquired, when you think it’s you who’s making the catch.

Mitchell never makes things simple. Nor needlessly complex. The music on these songs flows like water running downhill, switching this way or that not for the sake of it but because it must. Its course is unpredictable and ineluctable; once followed, it could not, you sense , have gone any other way. The same is true of the feelings and images it carries along. They are as plain and as complicated as the lives they invoke. So there is no easy dichotomy whereby women at liberty are happier than women trapped by men, or by themselves. Freedom has its own hazards. “Since I was seventeen/I’ve had no one over me,” snarls the narrator of ‘Don’t Interrupt The Sorrow’, the scene of a fierce and terse battle of the sexes in which ancient, Abrahamic patterns of domineering and resistance play out via the mores of the day. Religion clutches at everything. ‘Out of the fire like Catholic saints/Comes Scarlett and her deep complaint.” Woman as something wounded. Woman as something bloody and unbowed. Woman as something red, aflame and dangerous. This is ‘Shades of Scarlett Conquering’. A lambent piano ballad, invoking Gone With The Wind and depicting a creature of unblinking will: ‘It is not easy to be brave/Walking around in so much need… Cast iron and frail/With her impossibly gentle hands/and her blood-red fingernails.’ Mitchell unfolds the femme fatale from the inside, in the most delicate and ingenious reverse origami, and makes you quiver at the truth of it.

The Hissing Of Summer Lawns closes even more anomalously than it opens, with ‘Shadows And Light’, a breathtaking choral and synth meditation; a Gregorian chant made so modern that, after 45 years and countless hommages, it still sounds as if it is beaming in on a mainline from the future, in a steady rush of ideas and sound. Again, Mitchell pulls in and juxtaposes images, this time creating a gorgeously tempered aural collage. It is a song about meaning, about the futility of the binary, about the way meaning itself hides in shades and creases. It is among the most extraordinary four minutes in the history of popular music. You can take it as an epilogue for the album; a commentary on all that’s gone before; a guide to how to hear it. It certainly works that way. It also stands entirely alone. As, amid her hordes of disciples and imitators, does Joni Mitchell – and never in more enrapturing fashion than on this subtle marvel of an album.