Hexus is a new small-run print journal placed somewhere between the boundary of experimental fiction, art writing and visual art practice, with a focus firmly on horror — bridging Hammer Horror schlock and The Shock of the New, we aim to offer a more contemporary perspective on a much-maligned genre. We’re fundamentally excited by challenges to convention, experiments in form and the subversion of the expected; to finding a place where ‘horror’ is found, perhaps, outside of the reflection of its own red-eyed, recognisably grisly face.

Our first issue, The New Black, dwells on (and in) the darkness of dissolution—of body, mind, and spirit. Within its pages you’ll find writing and artwork from an international and highly acclaimed line-up, all dealing in their own way with the loss of self — be it through mental deliquescence, the narrowing strictures of power, miasmatic bleeding out, the price of fame, spectral malevolence, Dadaistic tumbles into the void, or good old-fashioned violence.

Issue one features new writing from M. Kitchell, Gary J Shipley, Michael Cisco, Brian Evenson, Philippa Snow, and Thogdin Ripley, and artwork from Dawn Arsenaux, Angela Deane and Fran Cutler. Issue two is due for release early next year. We welcome submissions. Each issue is themed so please do contact us before submitting. —Thogdin Ripley.

It Erases the Sky

Gary J. Shipley

The sky seemed to peel back—like it was a sticker, like it was a sea receding ‘til it disappeared. But unlike the sea there was nothing there behind it, no equivalent sand or shingle, no fish, no decomposing swimmers. There was nothing and our brains weren’t made for it: we puked like babies, like those heroin addicts getting the cure at Saraburi. We puked and we collapsed and we looked at the ground and we crawled through the contents of our stomachs to get back inside. We knew that if we looked up again our temples would crack and our eyes would bleed and our brains would try to escape through our mouths. One more glimpse of that expanse of what had gone and we wouldn’t be coming back. Once had been enough to mangle our consciousnesses beyond all thought of repair; a second encounter would suck out what was left, fear and its attendant reasons, leaving behind the faint outlines of billions of stranded human shapes mirroring the sky. After we’d healed a little and our homes had begun to resemble the family-sized coffins we’d always suspected they’d become, our curiosity returned. It came like a curse, and went with every new death, only to return again. Cameras and video recorders were used in an attempt to weaken the impact, in the belief that the image viewed via something else might find itself sufficiently diluted. Unfortunately, our findings did not support this hypothesis: it got you through the screen just the same. The animals that had followed us in soon became our best hope, when at six-monthly intervals we’d send one outside on a leash. We’d remove a small panel from a window and monitor their progress. When we pulled those first ones back in, it was hazardous just to look at what was left. It was as if their bodies had been sifted through a tight mesh and then put back together again. Although they weren’t dead, they smelt like they were, like they’d been dead for a while. If the other animals caught sight of them they’d hide under furniture and wouldn’t surface for days. When the test animals did stop living they didn’t die so much as lose the ability to occupy space. They’d gutter and glitch, becoming increasingly aberrant in their movements and spatial coordinates, until as far as we could tell they weren’t there anymore. It took years but eventually they too stopped looking up. They’d cram their heads into their bellies or their faces into the concrete and would refuse to move ‘til we allowed them back in. Now nobody knows whether the sky is back or if there’s something else there in its place. Although something we’ve become sure of is that whatever replaces the sky, if anything ever does, will certainly destroy us. Our heads are full of dirty grey spacecraft the size of small countries suspended above us with intentions beyond our nascent capacity for terror. If the sky returns to us when we sleep it is white and patterned like our ceilings.

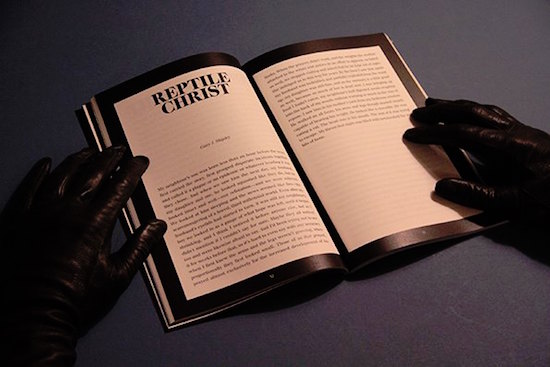

Reptile Christ

Gary J. Shipley

My neighbour’s son was born less than an hour before the news first carried the story, first grouped disparate incidents together and called it a plague or an epidemic or whatever heading it was they chose. And when we saw him the next day, my husband, my daughter and me, he looked squashed like they do, but he looked intact and well—our refutation—and we were relieved. We looked at him sleeping and the news seemed like lies—the scaremongering of a bored, third millennial world. Even after my husband’s eyelids had started to turn, it was still my neighbour’s boy we looked to as a gauge of what hope was left, until it began shrinking, and I think I noticed it before anyone else, but as I didn’t mention it I couldn’t say for sure. Maybe they all noticed too and were likewise afraid to say. And I’d been trying not to see it for weeks before that, so it’s hard to even say with any accuracy when I first knew the arms and the legs weren’t growing, when proportionally they first looked small. Those of us that prayed, prayed almost exclusively for the increased development of his limbs. When the prayers didn’t work, and the weights the mother attached to the wrists and ankles in an effort to appease us failed as well, we stopped visiting and asked that he be kept out of sight. She indulged us in this way for years. By the time I saw him again my husband was bedridden and partially exploded from the waist up; my daughter was still fine, and so the memory is a little good as well, because so much of her is dead now. I was bringing up food I hadn’t eaten, my neighbour’s half-digested meals erupting into the back of my mouth without warning or much in the way of repose. I saw him in his mother’s yard from my bedroom window. He walked on all fours, his arms and legs though stunted clearly capable of bearing his weight. He looked like a crocodile. He was eating a cat. The head was in his mouth. The rest of it was trying to escape. My throat that night was filled with tortoiseshell fur and bits of bone.

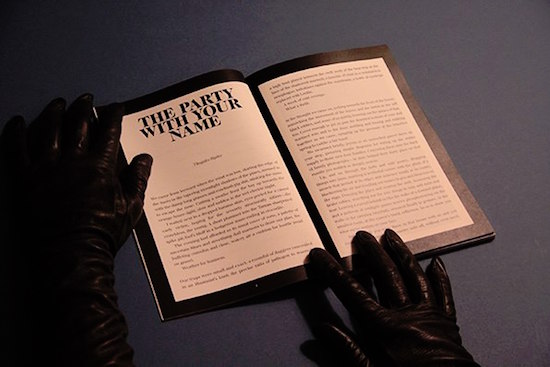

Begat

Philippa Snow

Demi Moore on laughing gas, and Kanye in Kim Kardashian’s ass; a tax check opened with the famous pelvis of the supermodel Anja Rubik, and a Twitter death hoax, brought into being by sheer bloody-minded collective longing—the kind of frenzied fever dream in which Christ, moving in His mysterious ways, manifests Himself on the government-grilled-cheese sandwich of a super-believer. Gym, Tanning, Laundry, and Eat, Pray, Love, and the unbearable smugness of being James Franco: the sixteenth-birthday nose-job, and the thirteenth-birthday blowjob; Lady Gaga Recovers From Hip Surgery In 24 Karat Wheelchair. A paparazzo masturbating to the high and exquisite zygomatic arches of Natalie Portman; to the probably-hairless preteen pudenda of Natalie Portman in Leon: The Professional; to a nipple-slip shot of the underage Kendall Jenner; to a milk-carton pageant child. The ex-Disney actress—in stainless and shroud-white Hervé Léger—explaining to Oprah Winfrey, through the crocodile tears of the brainwashed ex-addict, that normalcy is not interesting; that she has only done coke maybe ten or fifteen times; that she is aware that this is a televised execution; that she is not sorry. A trepanation in the skull of a third and less important Hilton sister, and a neon straw in the burr hole; Cannibal Cop Credits Bondage Fetish to Cameron Diaz in The Mask. Miley Cyrus on Naxalone, twerking for a cameraphone, and Macaulay Culkin, Home Alone in His Trippy, Two-Million-Dollar Drug Den. Lash LaRue and the gloryhole screw, and South Beach Wanda—the famous Whitney Houston drag impersonator—shot in the head in a Florida bedroom, and bleeding out to the sound of I Have Nothing. (Six months later, unrelated: Policeman Accused of ‘Inappropriate’ Treatment of Whitney Houston’s Corpse.) A telephone, off the receiver but ringing, somehow, the sound suggesting the screams of a dying television anchor overheard from the next room. The Air Conditioned Nightmare; the Amanda Bynes elliptical incident; Alicia Silverstone Organises Breast-Milk Swap-Meet. High school shooters scoring gory front-page psycho stories in the New York Post, and the final season of Dance Moms; the general idea of Jenny McCarthy; the sound of a rubberised replica of Farrah Abraham’s vagina, clapping, as one hand in the proverb. A magazine coupon for facial reconstruction, where “reconstruction” means the arrangement of the face in the approximate shape of Scarlett Johanssen’s; Teenage Murderer Confesses to Killing Mom and Sister (“I am pretty, I guess, evil… Whatever”). Justin Timberlake Says: “I Am America.”

Gary J. Shipley is the author of numerous books, including You With Your Memory Are Dead (Civil Coping Mechanisms, forthcoming), Gumma Homo (Blue Square), and Dreams of Amputation (Copeland Valley). His work has appeared recently in Fanzine, Sleepingfish, Vice, Hobart and others, and has been described by 3:AM Magazine as “a fearless attempt to advance the art of literature, to force us to breathe something, to drown in something, to bloody our hands… an unforgettable experience.” More details can be found at Thek Prosthetics [http://garyjshipley.blogspot.co.uk/].

Philippa Snow is the co-editor and co-founder of Hexus, the features editor of Modern Matter, and a freelance writer for a variety of other publications. She recently contributed a series of experimental fiction texts to Metallen, published by Ditto Press. Her essay collection, The Diseases of the Era: Body Horror and Modern Celebrity, is due for release next year.

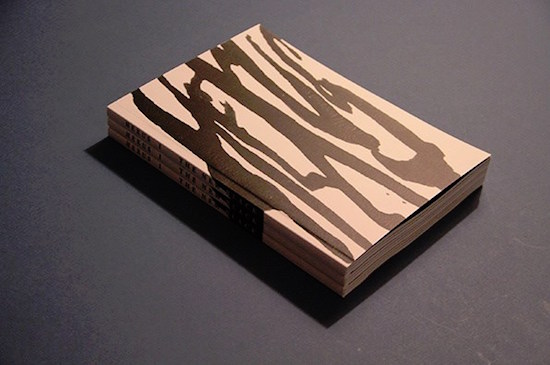

Hexus Journal: cover price: £12.00, numbered edition of 200.