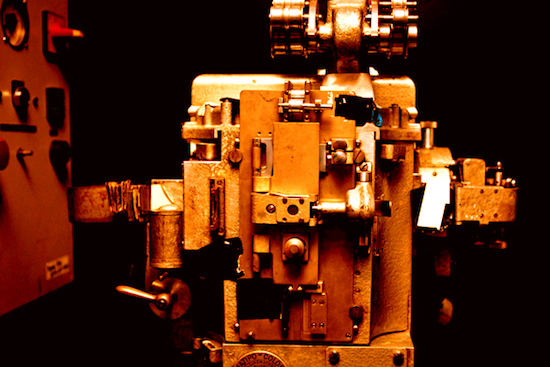

no.w.here’s 16mm contact printer

"The thing about film," Karen Mirza says to me, "is that it’s actually a really durable medium – even though it has this fragility." She immediately corrects herself: "– it feels like it should be fragile."

We’re sitting round cups of coffee at No.w.here, the project space and production studio Mirza set up with artistic collaborator Brad Butler, eleven years ago. The room is filled with hulking mechanical beasts – an optical printer, telecine, processor, contact printer. The shelves heave under the weight of stacked film canisters. A ‘washing line’ on which to dry strips of film bisects the room, presenting a potential garotte for anyone very, very tall walking carelessly.

For over a decade, No.w.here has been more than just a processing lab, work studio, and exhibition space; it’s been the centre for a community of artists, and a source of continuity for a radical creative practice dating back to the London Film-makers’ Co-op set up by Bob Cobbing, Jeff Keen and Stephen Dwoskin in 1966. But it nearly didn’t happen in London at all.

"When we went to set up No.w.here we had to look outside the UK because everything had been collapsed here," Mirza explains "There was a lot of activity at that time that had been structurally defunded or transformed into this new shiny model: the service model. We were looking at the more self-organised [models]. We looked to Paris and to New York."

Mirza and Butler first established the name No.w.here for a programme they curated of British artists’ film and video work at the Robert Beck Memorial Cinema on New York’s Lower East Side, back in July 1999. They were not long out of art school at the time. The screening was packed."That energy is what gave us the impetus to come back."

They had met at the Royal College of Art between 1995 and 1997 and decided to collaborate. "We made one short film together," Mirza says, "and that was supposed to be it. But then it just went on to be twenty years of praxis." Butler and Mirza’s work together is at once poetic, experimental, and trenchantly critical. Their recent film, Deep State, co-written with China Miéville, feels at times like an Adam Curtis documentary recut and remixed by Chris Marker, referencing psychoanalysis, Occupy, William Burroughs, and Zimbabwean poet Bambudzo Marechera – all in the first ten minutes. An earlier piece, 2003’s two-channel installation Where a Straight Line Meets a Curve, is more meditative. Shot within a single room, it explores the way light and sound conspire to form – and are in turn formed by – architectural spaces.

A workshop taking place within the lab

Following their success in New York, Mirza and Butler returned to the UK and began a roving programme of events combining new work and old, avant garde film and more performative expanded cinema works, in free spaces around London. Meanwhile, Mirza volunteered at the Lux Centre in order to gain access and training with their film processing equipment. With its roots in the radical artists’ coops of the 1960s, the Lux Centre for Film, Video and New Media had opened on Hoxton Square in September 1997 with its own dedicated gallery, cinema, and production facilities. It was the result of the merger of the London Film-makers’ Coop (itself a child of the 60s underground scene around the Better Books shop on the Charing Cross Road) and London Electronic Arts.

"It’s hard to imagine this new centre failing," artist and curator Sarah Turner had written in Vertigo magazine as the Lux prepared to open its doors for the first time. Everything about it was purpose-built and state of the art. Unfortunately, the Lux never owned its own building. By 2002 the rapid gentrification of surrounding area would send local rents skyrocketing, forcing the Lux out. Lux continues to this day as a registered charity with an office but no cinema or production suite of its own. Its focus, today, is on preserving its important archive of historical artists’ film and video. The former site on Hoxton Square is today occupied by an indie rock venue with a trendy bar attached which, according to Time Out, "attracts a friendly mix of creatives, tourists and City boys."

The closure of the Lux had left London’s moving image artists without a centre. All the equipment that had once belonged to the Film-makers’ Coop ended up dismantled and shoved into a lock-up in Hackney. Suddenly there was this gaping hole, one that – almost without knowing it – Mirza and Butler had been preparing themselves to fill for the past three years.

Some of their earliest work together had been screened at the Lux Centre. While working there, Mirza had repeatedly petitioned her employers to curate a programme on the dormant Monday evening, say "as a younger generation, can we have access to the collection, come in, screen stuff, talk about ideas, talk about production." The suggestion was always met with interest, but never came to fruition. "There was always a split in the argument between Brad and I," Mirza tells me. Butler favoured striking out and doing their own thing; Mirza was more cautious. "I was more like, I don’t want to set up another faction. This is the centre for this practice and the history of these works is in this centre." But the Centre could not hold.

No.w.here’s first physical space was a split-level garage in Kilburn. There they housed the equipment that once belonged to the London Film-makers’ Coop, providing access and training, and also produced public events and screenings. Three years later they moved to their current location, above a shop on the Bethnal Green Road. Now it is No.w.here itself that is threatened by the march of gentrification.

"We were celebrating our tenth anniversary when we got the notice of eviction," Mirza tells me. They had always got on well with their landlord. He came along to the events, insisted they think of him as a friend. They had been just on the verge of signing a new nine year lease when suddenly everything went quiet. "And then the election happened," Mirza says, "and it was literally two weeks after the election, we had this horrible phone call to say the lease is off and don’t worry about this but can we just show some people around. We’re just going through an exercise but we’re looking into selling the building." As The Guardian reported in May, the Tory election victory had triggered a renewed tidal of property speculation in the capital. Suddenly the thriving community Mirza and Butler had spent years building up was under threat.

Artist filmmaker James Holcombe surveys film drying in the lab

An unlikely glimmer of hope came in the form of a piece of Conservative legislation. Coming into force in September 2012, the third chapter of the Localism Act provided for the preservation of "assets of community value" where a place’s current use, "furthers the social wellbeing of social interests of the local community." Mirza and Butler applied, and were finally granted the status just a few weeks ago. "What it does is that it puts us at the same table as the landlord and the developers," Mirza says. "It means they can’t shut us out of the conversation." The landlord is now in the process of challenging the council’s decision. There is an online petition intended to help persuade him otherwise.

"These things keep getting disbanded" Mirza sighs. "Each time something gets disbanded, it doesn’t get put back in the same way. It can’t. You’re always at risk of fragmentation and disillusion. It takes years to build a community. It takes years to build a constituency around practices that aren’t commercial. There’s nothing commercial about what we do. For me, No.w.here has been about building a safe space in which to take risks. I think we really are asking different questions that when we set out in 2004. Questions about how we live and how we organise. We want to be part of a whole other constitution, where these materials and ideas and this communal knowledge that’s been accrued can actually have a new social and aesthetic and political form."

No.w.hereis currently located at 316–318 Bethnal Green Road, London. Sign the petition to help keep them there