Seeing homeless people is not unusual in cities. A self-built homeless shelter on a busy main road is. Over recent years it has become more commonplace to see people camped out in tents in urban spaces. In 2011 the Occupy Movement camped outside St Paul’s Cathedral in London as a protest against capitalism. Since April 2015 people have been sleeping in tents at various sites in Manchester city centre and in August 2015 Manchester City Council (MCC) successfully applied for an injunction to forbid the setting up of homeless camps. They deemed the act of people sleeping in tents an act of protest against the Council’s homeless policies – an act which was illegalised through the injunction. Their reasons for this injunction are trespass, infractions against highway and planning laws and alleged public disturbance. The penalty for breaking the injunction? Two years in prison or a £5,000 fine. This is clearly criminalisation of those at the extreme margins of society and does nothing to address the issue at hand.

A Public Space Protection Order (PSPO) introduced by Hackney Council in April 2015 allowed the council to fine rough sleepers £100. A petition opposing this, which had support from the likes of Ellie Goulding, leading to Hackney Council amending the order. In May 2015 arrests in Birmingham for begging rose by 60 per cent. In Glasgow, homeless people were subjected to excessive stop and search by the police in March of this year. I wanted to find out how we had ended up in this position, with homelessness becoming a crime and people setting up camp on the streets.

Recently I interviewed Jen Wu of The Ark to find out more about the project. She explained: “It’s basically a safe zone and it was built by someone who is homeless but was enabled to grow with public support. For me it’s a zone that represents protection from aggression and attack by the very same government which intervenes in peoples’ daily lives – especially the people that it has made homeless and abandoned. All the protections and rights that you are given as a taxpayer, as a member of the public, are taken away when you’re deprived of an address and then you’re aggressed, attacked, terrorised and left vulnerable. So in this protection zone it’s been an exchange amongst the people which is pretty extraordinary."

Safety is a key issue here and the desire to feel safe is especially important when people are at risk. It is common sense that there is safety in numbers, yet homeless people are rarely talked about (in the media at least) as being vulnerable or at risk. They are more likely to be represented as being a potential danger and a risk to others’ safety.

I asked what sort of people come to the Ark: “Because we have things like food, clothing, we get, well, homeless people. And by homeless we mean straight homeless and also hostel people who are going through a rough time. People are affected by the system in very detrimental ways."

One of the common arguments against homeless people is that they are "not really" homeless and no doubt this is maybe true of some beggars. Jen is not homeless herself, but has been living at the Ark for the past months to offer her support for the camp. I asked if she saw herself as a campaigner and she replied no, saying she saw herself as someone providing health and emotional support and "definitely not a protester". She described her actions as "emergency humanitarian aid".

The issue of addiction to alcohol or drugs is often associated with homeless populations, whether it is addiction that led to them ending up homeless or vice versa. At The Ark whilst it is appreciated that people do drink, drinking openly during the day is not encouraged, but is permitted in the evening, as this is generally culturally commonplace. There is also an expectation that residents of The Ark are making an effort to get off the street. You can read more about the founder of the Ark, Ryan McPhee, here in this Vice UK feature.

Continuing on the theme of safety, she says: "It’s about giving people a chance to have a life, so for that reason if we can see people endangering themselves, we try and intervene… When you talk to people on the street, yes, of course we want to get them housed but it’s not just about that, we need help to get them through these things, which [just] throwing someone into detox for 8 weeks or something is not going to actually solve the problem."

More recently the Ark have seen a different type of resident requiring their help. Jen explained: "It’s not [just] to do with people being highly addicted to something and unable to cope you know; it’s not really happening that way [currently]. It’s all about bureaucracy. People are being sent out into the streets. I’ve been hearing about people being sent out into the streets and it’s not their fault." The bureaucracy she is talking about includes the bedroom tax and other sanctions on those on benefits or in occupying social housing – such as those who fail to turn up for an appointment often having their benefits stopped for six weeks. A period easily long enough for someone to be made homeless for not paying their rent. The modern make-up of the homeless is changing, for example, there are many more ex-servicemen living on the streets now than in recent memory with one in ten homeless people having a military background. Homelessness has risen six-fold since 2010 in Manchester. This is not a statistical aberration. The homelessness crisis in London and the lack of emergency hostels has led to the charity New Horizon Youth Centre giving young homeless people bus tickets so they can stay safe on public transport instead of remaining at risk on the streets.

I asked what sorts of changes Jen would like to see made to the infrastructure and she said that more professionals, particularly mental health professionals, need to be provided. The Ark provides protection, shelter, community, food and clothing where it can but support services are necessary as well. When asked about the project’s goals, her response was: “We’d like everyone who wants to be under a roof in a safe place to be able to realise this desire. There are enough empty properties for this to happen (…) I think for people, especially people who need to be in a safe place, that’s not too much to ask for and that is entirely possible."

MCC have reported, via the Manchester Evening News and the BBC, that residents of The Ark are not actually homeless but protesters who have been offered accommodation and refused it. But, according to Jen, the council have not visited The Ark regularly to check on anyone’s welfare or to canvass their opinion. They have, however, visited the encampment, with police back-up to serve an injunction on its residents.

One member of the group of officials in the clip does mention the surgery at the Booth Centre (a local charity based in Manchester Cathedral). The surgery is open five days a week (Monday to Friday, 9am-3pm) providing cooked food, shower facilities, toiletries, access to the internet, advice from trained volunteers, support for those who need to claim benefits and advice for those with health, drug and alcohol issues, not to mention help to secure accommodation and employment.

Representatives from MCC, the Urban Village Medical Practice, Shelter and other organisations are partners in this scheme. Additionally, the MCC have repeatedly said that they don’t want to see people in prison. Furthermore, they have denied allegations they have not engaged regularly with the homeless. Nigel Murphy, MCC’s executive member for neighbourhoods, gave this statement on September 18: "Members of our homelessness unit were on site this morning – as they have been on a regular basis since the first camps appeared in April – to offer accommodation, help and support to anyone who needs it. I am pleased to say that five people accepted our offers and are now in accommodation this morning as a result of the homeless team’s work – some of these people are in a building we have recently been working hard to open up as a residential unit to accommodate rough sleepers. […] Like the protesters, we don’t believe anyone should be sleeping rough on the streets, and we sympathise with the plight of all genuinely homeless people, but some people connected with this camp are not homeless and have their own accommodation." The full statement can be viewed at

However, this doesn’t tally with what I was told. A report in the MEN on September 9, 2015 states the MCC have spoken to 72 people from the camps, 17 of which have refused help, but 24 have been found accommodation. This does not match with Jen’s experience. Also, it is not clear whether this is permanent accommodation or just emergency housing, usually only offered for 48 hours after which people find themselves back on the street again.

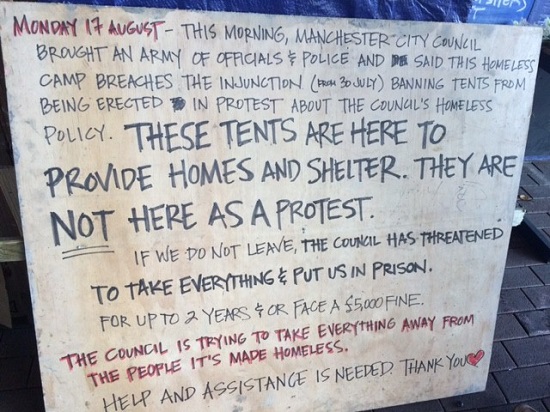

The issue of labelling The Ark as a ‘protest’ is a recurring issue in the media. Despite signs such as the one below being displayed at the site on Oxford Road, the authorities continue to talk about ‘protesters’. The introduction of the Anti-Social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Bill 2014 grants police increased dispersal powers and introduce the IPNA (Injunction to Prevent Nuisance and Annoyance) which has replaced the ASBO. (More on this wide-ranging, potentially pernicious law here.)

The 2014 bill also grants public space protection orders whereby those causing ‘nuisance’ can be removed and injunctions will be granted against anyone engaging in or threatening to engage in anti-social behaviour. It seems somewhat ironic that The Ark is facing an injunction from MCC (the court hearing takes place today, September 30), given that, from what I have observed, it appears to be operating in a completely social manner, building strength in numbers, encouraging socialising among homeless people and members of the local community, helping out those in need and trying to provide shelter and safety for the vulnerable.

In fact this seems to be exactly the kind of behaviour encouraged by David Cameron’s Big Society. In the Cabinet Office document ‘Building The Big Society’ the claim is made: “We want to give citizens, communities and local government the power and information they need to come together, solve the problems they face and build the Britain they want." You would think, in that case, that they would celebrate projects like The Ark and not allow local government to prosecute them. The Ark is making every effort to address the problems it faces voluntarily and simply needs more resources and the threat of the injunction to be lifted to carry on their work.

The Ark provides a safe space unlike some of the hostels and bed and breakfast accommodation offered to rough sleepers. When asked about why hostels may not be the best place for homeless people, Jen explained: “So, you might end up in a hostel but these places are really unstable, they can be very abusive, unsafe places, but your tenancy there is not secure and you don’t have an opportunity to get stable enough to progress and build yourself back up. But there’s so many people in these hostels and then people back on the streets.”

Another issue with these types of accommodation is that they very rarely have facilities such as laundries and kitchens. A pregnant woman and her partner I talked to earlier at The Ark were currently living in a bed and breakfast, not ideal given the amount of washing and drying of clothes a new-born baby creates. And it is not just the lack of facilities or safety that is a problem. When asked why people at The Ark weren’t in at least emergency council accommodation, Jen claimed there was a lack of places as the council had sold off much of its housing. This means it is usually third party providers, who are a mix of charities and private companies, who are supposed to house the homeless.

No two cases of homelessness are the same, as this example from Jen shows: “I talked to a 19-year-old and an 18-year-old who were sent to the streets. One wasn’t housed because he came from another city but he had been in a care home in Manchester for several years, so when he turned 18 they turfed him onto the street. After he went to the council housing office they claimed they no longer had a duty of care for him: ‘You’re 18, you’re schizophrenic, you have ADHD, you have depression but guess what, off you go.’ The other one, a 19-year-old, born and raised Manchester, had ‘a bit of a criminal record but not for anything serious, they didn’t want him there, that was it’. These types of stories often go unheard as homeless people are dehumanised and presented as the problem by the mainstream media."

The homeless are a group not catered for by planners and capitalists. They are ‘designed out’ of urban spaces in subtle ways, with the creation of benches which are impossible to sleep on, bus stops with slanted perches instead of seats and (in London) spikes that have been placed in doorways by developers and local authorities. This is not a new thing. As early as 1990, Mike Davis’ book City Of Quartz described "bum-proof" benches designed to prevent anyone lying horizontally on them in Los Angeles. In Manchester there is an absence of free public toilets, which has an impact on the homeless. Jen revealed: “The homeless get charged for public urination, defecation, whatever; well, what are you supposed to do and then if you don’t have the rights to be anywhere, what are you supposed to do, where are you supposed to go? You’re not allowed to shit anywhere, you’re not allowed to sleep anywhere, you’re not allowed to do anything, so what are you supposed to do?” This level of zero tolerance towards the homeless was first seen in Mayor Giuliani’s clean-up of New York. Parks in the city were closed at night to prevent homeless New Yorkers sleeping there and a zero tolerance of panhandlers – beggars – was implemented to ‘solve’ the problem of homelessness. In reality, it simply displaced homeless populations elsewhere temporarily. A United Nations report lists New York as still having the second highest homeless population (66,000) in the world in 2013.

So what sorts of solutions are there to combat homelessness in a socially and morally acceptable way? It makes sense to look at countries with low rates of homelessness. In Europe, Denmark, Luxembourg and Austria have low homelessness rates. Danish policy states that "no citizen should live life on the street". They are putting money into services and converting housing for the homeless and doing outreach work. In Finland they have a strategy to end homelessness which includes building supported housing to replace dormitories (the Finnish equivalent of hostels). Luxembourg has a national homeless strategy and is committed to a housing-led approach. Examples of good practice in Austria include advice and counselling, recreation activities, employment and training for the homeless.

In England, responsibility for the production of homeless strategies falls to local councils, so each have their own way of dealing with the problem. Nationally, the government have produced their “Vision To End Rough Sleeping: No Second Night Out Nationwide" document. And this does acknowledge the need to provide access to health care in particular for drug, alcohol and mental health issues and has employment for the homeless as one of its commitments, but nowhere does it mention building more homes or actually consulting with the homeless people themselves. And seeking to engage with, rather than criminalise, the homeless population would be the first step in the right direction.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of Manchester Metropolitan University

If you want to find out more about The Ark they have a page on Facebook where you can donate to their gofundme account. There is also a petition with 3,500 signatures and counting at <a href=”https://www.change.org/p/mmu-manchester-city-council-cease-possession-save-the-ark-manchester-s-only-emergency-homeless-shelter-4-all” target “out”>Cease Possession Save The Ark