All photography by Al Overdrive

“Which one of my records is coming out?”, asks Jock Scot, the Leith-born poet laureate of the binge-drinker, connoisseur of the legendary Willie McGonagall and renowned supplier of ‘good vibes’ to the likes of Ian Dury, Dr. Feelgood and Vivian Stanshall. We’re sat in Jock’s north London living room with the artist and filmmaker Robert Rubbish who is making a documentary film about Jock; also present is Lias Saoudi, the genial frontman of the Fat White Family. Both Lias and Jock share a discordant muse and today the discordance is fuelled by Jock’s array of whiskeys and ciders and all manner of alcoholic devilment; the power of positive drinking.

Before we get a chance to steam in, Jock answers his own question. “Is it My Personal Culloden, the one with Davey? Well, that’s fucking great because that’s the best one!” Originally recorded and released back in 1997, My Personal Culloden is a collaboration between Jock and Nectarine No. 9 man Davey Henderson and is being re-released by Heavenly Records. Jock is a funny, sour, savage writer and the album stings with an atmosphere of gnarling paranoia, imprisoned minimalism and disenchantment with love and the capital punishments of London town. Most of Jock’s characters wage an internal war with their limited circumstances but, of course, there is a thin line that separates laughter and pain and comedy and tragedy and he fearlessly straddles these extremities of emotion. “It’s even better that the album is being re-released,” continues Jock. “Because I’ve not got a copy.”

The songs on My Personal Culloden are startling in their rampant, marauding acerbity. “Eyes bulging from your throat… with a rope round your neck and your raping penis erect, stopping short of the deck, it’s a fatal effect. Swinging. Dodgy.” That’s a quote from ‘Norma Vaughan Blues’, one of the most brutal and effective songs on the album and one which also serves as Scot’s personal plea to bring back hanging for sexual offenders. Even the song titles betray a dark and depraved nomenclature: ‘There’s A Hole In My Daddy’s Arm’, ‘Just Another Fucked Up Little Druggy’. Davey Henderson’s musical backing ranges from the borderline industrial to the sparse and indeed, it is within the latter atmosphere where My Personal Culloden truly shines as this leaves Scot’s heavily accented reading voice room to breathe. Almost twenty years on from the recording of the album, Jock’s voice is still insouciant and insinuating with every single utterance.

“Here’s to the Little White Family [sic]”, cheers Jock in the direction of Lias. The latter has just returned to the UK this very morning following a Fat White Family gig in Sicily; however, Robert Rubbish expresses some surprise at the relatively fresh state of mind which Lias appears to be in – no discernible traces of a hangover or comedown whatsoever. “Yeah, we’re the junkie band – I get that a lot,” Lias responds. “People down in Peckham, they don’t talk to me anymore, they don’t trust me.” “But that’s nothing to do with the band,” counters Rubbish. “That’s just because of your personality.”

Indeed, the personalities on display this afternoon are quite striking in their differences. The Jersey-born Robert Rubbish is suave, flamboyantly suited – “I bought this tie from a junkie on the Kingsland Road for a pound at three o’clock in the morning,” he proudly exclaims – and has celluloid form with both gentlemen; two years ago, he made a quite demented psychogeographical, hard-boiled detective film called A One Eyed Man In The Kingdom Of The Blind with Saoudi in the starring roll. Today, the famously provocative Fat White Family frontman is effusive in both his cigarette smoking and evocations of his wandering childhood through various parts of Northern Ireland, Scotland and Yorkshire. Dressed all in black, ignoring Rubbish’s muttered jibes of ‘fucking hipster’, Saoudi is eager to engage in political debate, having just joined the Labour party on the back of Jeremy Corbyn’s ascension and adamant in his suggestion that we should all "just move up north". When I announce that I am familiar with A One Eyed Man, Saoudi tartly responds, “You must be one of the three people who’ve actually seen it then…”

Meanwhile, Jock is insistent on sitting on his own chair, directly in front of his television set which he’s become suddenly indignant about: "I’ve not got a copy of that bloody documentary either! But it doesn’t matter because I’ve not got any [technology] that works. The ceiling fell and it broke the DVD machine. I’m bad with modern technology; I just have to look at it and it stops working.”

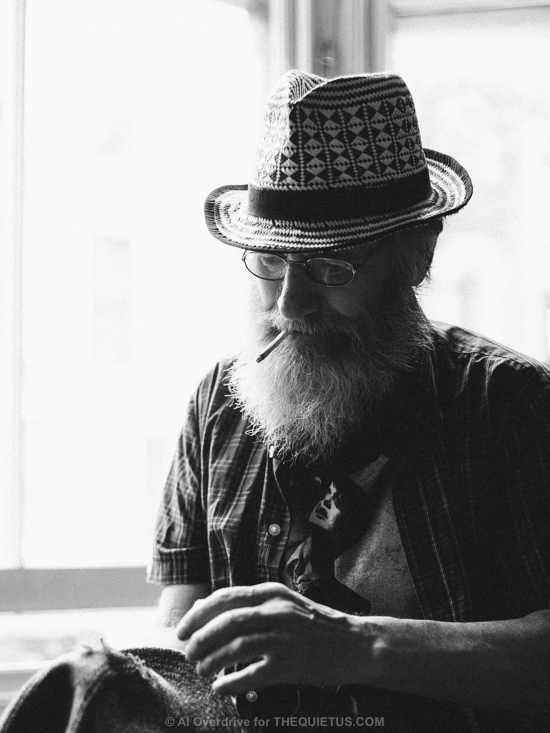

The walls of Jock’s house are adorned with images from the glory days of Stiff Records – in the corner, Ian Dury stares menacingly at anyone daring to match his glare. Dury was a major influence on Jock’s ascendance into the music industry; after a chance meeting at a gig in the late 1970s, Jock became Ian’s right-hand man, always sporting a skinhead, kilt and Doc Martens. While the attire may have changed somewhat over the years – today he is elegantly dressed in tweed suit, a hand-knitted trilby and matching scarf – Jock still maintains a brooding, forceful presence, keenly surveying the drinking and the conversation with an air of wizened perceptiveness – a true street poet, perhaps.

There’s an air of easy familiarity between Jock and Robert Rubbish. This is because Rubbish has spent the last eighteen months with Jock making a documentary on his quite astonishing life and, at the moment, is attempting to round up some funding to finish the film. Rubbish is expansive in his descriptions of the making of the film as it coincided with some catastrophic developments in Jock’s existence. “Aye, he started to come up to film me because he thought I was going to be dead in a few months,” says Jock. Lias is incredulous at the severity of this statement. “Why did he think you were gonna be dead in a few months?”, he innocently enquires.

“I got diagnosed with cancer [in 2014],” replies Jock. “I remember thinking I’d hopefully live long enough to see the World Cup. They were very funny about giving me any definites. I said ‘Look, put your cards on the table. What’s the story here? How long are you giving me?’ They gave me three months.”

Rubbish takes up the story. “Before the diagnosis, we had just gotten some funding for the film. But after this news, we started shooting straight away and it all became a bit of a rush. We seemed to do an awful lot of stuff in a short space of time. We interviewed Humphrey Ocean, from Kilburn And The High Roads, who also painted a portrait of Jock. And then there’s people like Shane MacGowan, Pete Doherty, Neneh Cherry, Baxter Dury, Murray Lachlan Young, Salena Godden, British Sea Power…”

The experience of the outsider in London, so beautifully detailed by MacGowan in his early Pogues lyrics, is one which resonates with all concerned and immediately ignites the attentions of Lias. “I grew up in Ireland,” he says, “and when I came first to London at the age of eighteen, in a desperate bid to forge some sort of identity for myself, I decided I was going to be really Irish, I had this phase of drinking really strong cider and listening to the Pogues at an aggravatingly loud volume to anyone else in the vicinity.”

“I used to drink in a pub off Tottenham Court Road called the Spanish Bar,” Jock breaks in to inform us. “At the time, I used to collect records and there was a record shop on that street and Shane used to work there. He was the Saturday boy. And I used to go in to get records and I’d go for a pint and I’d get Shane to come with me. This was before the Nipple Erectors. But I went to see them a lot, he used to have a girl playing bass [Shanne Bradley], she was good fun. They had a little skinny guy who wore a suit and Nazi helmet. Shane used to take his strides off like Angus Young, at the end of the set. And then later, I was going to Pogues gigs. That’s when it all came to a head and everything exploded. They were playing mainly in pubs, when they started. Good night out.”

The realm of the pub is never far from our conversation. Jock, Robert and Lias all met – separately – amid the infamous world of the Soho drinking den, albeit one that is now a far cry from the louche and languid heartland of Jeffrey Barnard, Peter O’Toole and their jaundiced ilk. All three are effusive in their praise of the power of the local pub as community and the positive effect this can have for any struggling artist.

“I met Jock in the Colony Room in Soho probably about ten years ago,” says Rubbish. “And then I met Lias through his younger brother, a Northern Irish, Algerian, alcoholic, rent boy fashionista. I used to basically to take him with me and I would get the gay men to buy us drinks. He was so handsome but also rough but beautiful and dangerous. He’s like something you’d find at the Port of Marseille hanging around the toilet. And then I met Lias through him.”

Jock: “But Soho was always a mixed up place. People say ‘Soho isn’t what it used to be’ but someone else said ‘Well, it never was’. I remember being in the French House, just having a drink, just sitting, five o’clock of an evening and this girl came in with her handbag from her office. She was quite noisy, giggling, probably bloody sober, and she said ‘What is Soho coming to? They’ll only serve half pints at the bar.’ Well they only ever served half pints in the French House. She reckoned that was part of the downfall. Anyway, I think binge drinking has come back into fashion which is a good thing!”

“Pubs were the centre of a lot of scenes Jock was in,” says Rubbish. “But now you have to be a pretty well off person to be a regular in a pub. London appears to be: if you can’t afford it, get out.”

Gesticulating at Lias and Rubbish, Jock is suddenly indignant. “They want to squeeze all you lot out,” he insists. “They just want it to be a money-makers place. And half of them are fucking Russians. Russians are notoriously behind the times – except when they’re having a revolution once a century.”

One of Jock’s most favoured haunts was the legendary north London boozer Filthy McNasty’s, famous for its Guinness, twenty four variations of whisky and rather famous clientele. “Pete Doherty lived upstairs in Filthy McNasty’s,” remembers Jock. “Shane [MacGowan] stayed there too. The funny thing about that room was that Tommy, the banjo player in Shane’s band, also lived there but he moved out and eventually found a flat and the room was empty. But also [at this time] the pub changed management. And one evening, we all turned up, [mimes heavy drinking: scoop, scoop, scoop] and the new manager is there and the entire bloody celling fell in. At half nine on a Friday night. Because [the new manager] put in different speakers and it was the opening night of the new regime. And everyone’s pint was full of lumps of plaster. So it was a definite line drawn in the sand. I never went back there again.”

Of course, Jock Scot has spent the vast majority of his adult life living in London. He explains his birth in Leith as a mere coincidence (“My mother just happened to be up there doing the shopping”) and he is no supporter of Scottish home rule. “Nicola Sturgeon? I never liked her anyway,” he reveals. “ The SNP are Tartan Tories. Kinnock was the one who sold the whole thing down the river. I wouldn’t have voted for independence: crazy idea. I thought we were all Europeans, I was just getting used to the idea. But apparently, we’re not. It’d be crazy if we go for home rule, they’ll have to change all the road signs to Gaelic. And no one speaks fucking Gaelic.”

At this juncture, Jock temporarily leaves to procure more cider for the thirsty Lias. Back in the 1990s, our host appeared on MTV, reciting ‘The Mod Poem’ under the Jock Scot Experience moniker. In his absence, Robert Rubbish wonders aloud whether Jock should now return to our television screens: “He should have his own Hootenanny-style show.” Lias is suddenly incensed. “That poisonous imp,” he seethes. “We should all get T-shirts saying ‘Jools Holland Is A Cunt’. He’s a rancid little penguin man.”

The returning Jock is concurrent with the sudden upsurge in vicious diatribes. “Anything can be better than Jools Holland,” he says. “Because there’s something very evil lurking behind Jools Holland.” Lias is still openly fuming at the mention of the Squeeze man. “Wait a minute,” interrupts Rubbish. “Did he not let the Fat White Family on his show or something?”

"’Course he fucking didn’t.”

It’s rather appropriate that Jock’s album is entitled My Personal Culloden – everyone here is immersed in their own vicious battles: Robert in attempting to get the funding to complete his documentary about Jock and Lias suffering the indignity of a Jools Holland snub. As for Jock himself? “Well,” he begins, “when we were making the album I was on the phone to Davey the musical director and he said we need a title. The conversation developed and I said ‘Did you see that film about the Battle Of Culloden? And so we were yapping away about that and then I was yapping away about this girl who had been giving me the runaround and Davey says, ‘Oh so, it’s sorta like you’ve had your own personal Culloden going on’ and that was it. So Davey came up with it.“

“Did you have any actual music input on this album or was it just pure poetry?”, asks Lias.

“I had no influence on the music side,” he says. “I came up two afternoons and did the voices. The band were there for two weeks and made the record and it developed as they went along with it. Although I did find this instrument – it was a little wooden log that I found on a street with little bits of tin that you ping, about three feet long and there were big fuckin’ spiders and everything crawling out of it when I gave it to the drummer. We did use that on the album. But on the whole, I had nothing to do with it the first time it came out. I never signed anything, I never got paid for it. It appeared the first time and now it’s appearing again. Davey McIntyre [who appears on the album] are Creeping Bent and they work full time doing what they do. They seem to do all the backstage machinations. And I agree with whatever they say. But they did pay me. The first release never paid me but I didn’t care.”

As for Scot himself and his current condition, he has point blank refused chemotherapy and describes his status as ‘stable’. The man has no computer, no phone, no e-mail address, has not had a ‘proper’ job for the last thirty years and disapproves of most other poets bar maybe John Cooper Clarke and Mark E. Smith. It might be easy to dismiss the man as existing in some sort of arcane, hermetically-sealed vacuum but this is a misnomer; his sheer perseverance and existence on these fringes has massively influenced a dazzling array of artists ranging from the punk era to the modern day purveyors of raucous, anger-fuelled debasement such as Lias and his Fat White Family. Also, it makes perfect sense that Robert Rubbish is making a documentary about Jock. Accordingly, the simple fact of Heavenly re-issuing My Personal Culloden – for so long a lost, near apocryphal record – is a victory for brilliant and utterly profound (and often profoundly unutterable) outsider art.

My Personal Culloden is out now on Heavenly