Times may change but it’s the changes that happen to people that count the most and this is certainly something that holds true for the four original members of Black Sabbath. Formed in Aston, Birmingham, in 1968, Black Sabbath – singer Ozzy Osbourne, guitarist Tony Iommi, bassist Geezer Butler and drummer Bill Ward – unwittingly tapped into the ennui and anxiety that ran through the lives of young urban rock fans during a time period of televised war, civil unrest and down-turning economic fortunes to paint a picture sharply at odds with the perceived peace and love ethos of the day.

Forged in the industrial heartland of the Midlands, Black Sabbath endured more than their fare share of hardship as they honed their sound to evolve from heavy blues rock into something quite unique while slogging it out on the British and European live circuits. All of which makes their rise from a then derided outfit to lionised originators then to international musical institution all the more remarkable.

But with huge success comes even bigger pitfalls. The band’s excesses throughout its imperial period of the 1970s has been well documented but it’s the band’s recent contractual disputes with Bill Ward that have kept the Black Sabbath name in the headlines. With all this hullabaloo, one can’t help but think that what should be a triumphant end to one of rock music’s most original bands is really a full stop mired by arguments among those four lads from Aston who managed to break out of their humble surroundings to become a planet-shagging monster.

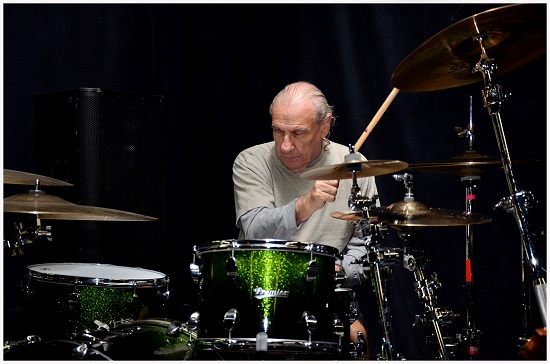

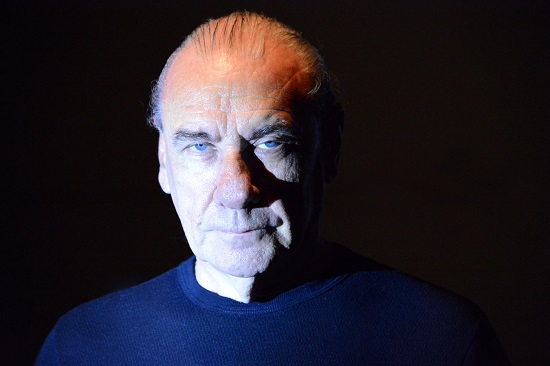

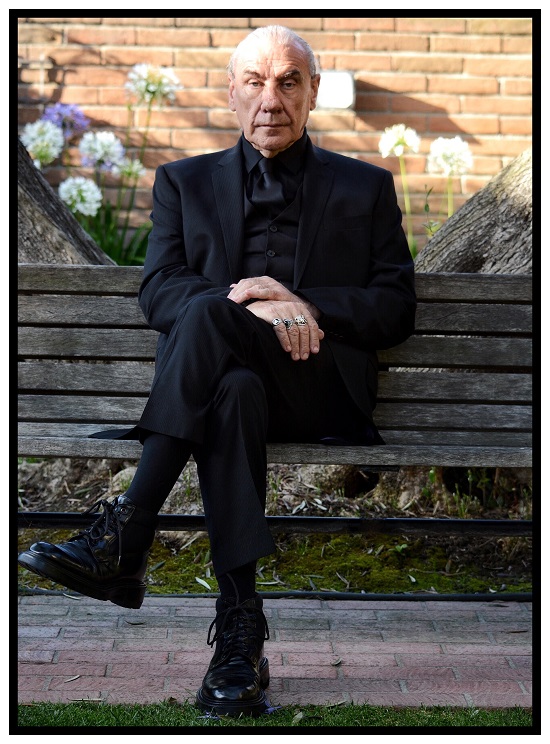

Speaking to Bill Ward via telephone from L.A. tQ is struck by the drummer’s colossal pride at what the band achieved, his candour concerning his addictions and his desire and determination to secure a measure of dignity by having the importance of his role in the band recognised by the kind of contract that he feels would reflect this.

Good morning, Bill. It’s 9am in LA – I guess that once upon a time this must’ve been bedtime for you?

Bill Ward: A long, long time ago! Y’know, when I was about 20 and that was 47 years ago. Bedtime these days is about 11 o’clock at night.

Let’s go back to the beginning. What was the first music you remember having an impact on you, and who inspired you to move behind a kit?

BW: The first music that I listened to was American jazz. My mother and father, during World War II, had a lot of American jazz records; the ones that the G.I.s had brought over. So as a child in 1952 – I was born in 1948 – I was listening to a lot of these jazz records. Every day I’d put them on the gramophone and it was the big band American jazz. That was my first impression and I loved all that. Then, of course, a huge dent happened upon me when I was about eight or nine years old and that was rock & roll: Elvis Presley. Up until that point I’d loved The Platters, The Ink Spots and I loved the R&B that was coming out of America, and then it was Buddy Holly and Little Richard and so I was brought up on all that kind of music.

And in England there was The Shadows. They were a huge fucking influence. They were a great band; Tony Meehan on drums and Jet Harris on bass; really great.

Is it true you were trained as a jazz drummer?

BW: Not really. When I was about 12 I did go to a music shop in Birmingham called Jones & Crossland and there was a jazz drummer there called Lionel Rubin, I think, and he played jazz and I’d watch him play. I’d just sit there in awe of him and go, ‘This is fantastic!’ When I was a young teenager I also had these opportunities that turned up; not because of any virtuosity but I’d be able to play with much older guys that were playing jazz. There were saxophone players, brass players and trumpet players and they were just jamming and they’d say, ‘Hey! Come and sit behind the kit.’ So I’d just join in.

When I was about six, my mother and father would always have parties on a Saturday night and they’d play all the popular songs from the war. And there was a drummer who’d come over and get very drunk so he’d always leave what were called his ‘traps’. And on a Sunday morning I’d sneak downstairs and that was when I first started fiddling around with drums. I was amazed by them.

I listened to the Boys’ Brigade as well. They used to come down our street on Sunday mornings and they were just brilliant; y’know, all the cornets were so shiny and I saw all the insignias on the drums and I was drawn to them like a moth to a flame. I so looked forward to seeing the Boys’ Brigade on a Sunday.

The essential ingredient to any successful band is the musical chemistry that exists between the players. Can you remember the moment when it clicked for you as far as Black Sabbath were concerned?

BW: I’d played with Tony Iommi since we were young; from, I think, when I’d just turned 16. He and I had longevity already and we’d been playing together in other bands and so we were somewhat used to each other.

I had a strange fascination towards Geezer Butler even though we hadn’t played together. I was just amazed by his appearance and there was something really odd about him. He was unusual, so different; he stood out a mile. I was very attracted to that and I remember thinking, ‘Wow, I wish I could talk to that guy.’ Eventually I did. When he was in another band called The Rare Breed, we used to play in a nightclub in Birmingham together – I was in a band called The Rest with Tony – and it went on until 8 o’clock in the morning and that’s when I met him. I’d get high after we’d played – or maybe I was high when we played – and the first time I said any words to Geezer was when he came into what was called the dressing room and he tried to climb up the wall. I was watching him and I was pretty loaded and kicking back on this couch and going, ‘Man, just look at him trying to climb up that wall!’ And he turned round to me as if he recognized me and said, ‘Try and try again!’ And I went, ‘Wow! That’s profound!’ And of course, he was loaded as well. I think he was on some major speed like Preludin and that was my first meeting with him and I thought, ‘I really like this guy!’

When I first met Ozzy, his appearance was a little bit different. I had really long hair, Geezer had really long hair and so did Tony but actually, Oz was a skinhead. Back then there was always trouble between long-haired people and skinheads and lot of people got hurt. And I thought, this isn’t going to work, but we went and we jammed and out came this incredible voice. I’d listened to enough blues by this point – I was 18 or 19 – and when Oz sang I thought, ‘Oh my God!’ What attracted me to him wasn’t his appearance but his voice. I thought, we’ve really got something here.

I felt the rawness of everything. Geezer, at the time, was playing rhythm guitar but there was something about the four of us that felt incredibly comfortable. I measured the way – and I still do it today – about how comfortable I felt in my surroundings and with people that I’m with and I felt completely normal and completely comfortable with those guys. The signals were that it felt good.

We all recognised at the same time that we had something good there and that was when we played at the Aston Community Centre. It was 1968 and we were so excited to play and we’d show up at 9am in the morning [for rehearsal] – because the only hours we could get were 9 ’til 12 – and utilise that time and make it all count. I didn’t know what we had but I knew that it felt really good.

Can you talk me through the composition and recording of the track ‘Black Sabbath’?

BW: It was actually at the Aston Community Centre and Tony came up with the famous three notes. It came out of the blue and it was like, ‘Woah!’ We were all just sitting around and we all just played it pretty much how it is on the record today. I don’t remember that we did a lot of stuff to it; it just kind of came out!

It’s quite strange, really, because a lot of Black Sabbath’s recordings – especially in the early days – just kind of came out. See, this was a band that was jamming together all of the time. When you’re jamming together you tend to have an inner frequency that suggests that you will intuitively know where the guys are going to go next. That’s what happens when you jam all the time and we jammed all the time: every single day we jammed and we always played together.

I always felt at that point in the early days, especially during the making of ‘Black Sabbath’, it was almost like we had a fifth partner, something that was invisible and untouchable that you couldn’t see. The songs weren’t coming out of fresh air because everyone was working hard but it almost had that feeling that the songs were before us and we had to grab them. As a songwriter today I still have that intuitiveness; I never know what’s going to show up on the breakfast table in the morning but then a song will be there before me. My job is to get that song which is a whole different set of thinking. It’s about knowing how to pluck them and how to get them.

Black Sabbath played the Star Club in Hamburg. Did the legacy of The Beatles have any impact on the band?

BW: I was very excited to be in Hamburg and I was very excited to be at the Star Club. I consider those days of our lives to be really, really good days. They were full of hardship and they were full of all different kinds of problems every day. The biggest problem we had every day was eating food because there wasn’t anything available and we would share one plate full of rice – and that was including our road manager.

They were very hard times but in hindsight I’ve reflected upon those days and I have very good and proud memories of them. We were so fortuitous because we always showed up on time, we played eight shows a day in the Star Club and we were playing on hallowed ground. Not only had The Beatles performed there but a lot of the Liverpool bands had gone there and everyone was going there. This was a historic place and it was like an apprenticeship school and that’s where we graduated. If you could survive Hamburg, then you could do well pretty much anywhere else. Those were remarkable days and now, at my age, I embrace them. Just wonderful, warm feelings and I think, my God, they were absolutely fantastic.

There are, to my mind, a couple of things that seem to get overlooked when it comes to Black Sabbath: you’re widely credited with inventing heavy metal but it seems like the funky side of the band tends to get ignored – I’m thinking of the breakdown in ‘Supernaut’ and tracks like ‘A National Acrobat’. Where did that come from? Where you listening to much funk back then?

BW: Tony is quite versed in jazz and I think that’s become more spoken about these days. When people look at our stuff in hindsight, they now realise how much jazz was being played in Black Sabbath. And I think it comes back from the childhood things that we learned and the influences of stuff that we picked up at the ages of around 13 and 14 through to our 20s like the blues. And R&B, of course, was really strong.

Also, we came from a city that had reggae. That’s often forgotten and especially for drumming because in reggae the one [beat], or the actual bass drum sound in reggae, sounds a little bit kind of off; it passes the rhythm. If you listen to Liverpool music [of the 60s] it had a 2/1 drumbeat, but in Birmingham people like [Led Zeppelin’s] John Bonham and myself and Micky Kellie from Spooky Tooth and others, we were playing in a different way. The ‘one’ beat was different and we were putting it in a different place. That’s almost like a jazz augmentation – just listen to Bonham on ‘Immigrant Song’ or ‘Kashmir’ and you’ll hear that the bass drum is just that little bit different and you’d have to say that it’s coming from an area of R&B/jazz. It’s not on top of the beat; it’s behind the beat. It’s different.

A lot of the drumming with Black Sabbath is behind the beat. It’s nice, especially when we played really slow because when you’re playing slow and the guitars are tuned down it gives this huge, erroneous, demonic sound and we fucking loved that! It was like apple pie and custard to us. At the same time, when you’re playing behind the beat, it holds it all down. I think I learned all those things listening to jazz and music that was that little bit different.

I can remember a time when Ozzy and I were about 21 and one of our favourite artists that we listened to at the time was Moondog. Moondog was out of New York and he played this marvellous saxophone and we didn’t listen to anything else. And were totally freaked out by it going, ‘Wow, this is fucking great, man!’ We were grooving on that.

Why do you think that a track like ‘Rat Salad’ doesn’t have people hitting the fast forward button, which is something of a rarity when it comes to recorded rock drum solos?

BW: I think it was real and it was done at a time when I was definitely in study. I’ve got to give credit to my peers. We used to do a lot of drum jams with a guy called Pete York from Spencer Davis Group and I used to listen to Traffic’s Jim Capaldi and I was constantly listening to John Bonham because we often used to play gigs with him before he joined Led Zeppelin. I was around all these guys.

And another guy I have to give credit to is Hughie Flint from John Mayall’s Blues Breakers who played on the Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton album. That was the most breakthrough album and Hughie’s solo, if you listen to it now, I just love where he went with it. It was out of time but it’s in time; it’s jazz. All these guys, to me, are such good rock drummers but they are all versed in some aspect and depth in jazz. They swing and they have all sorts of rudiments and they way they all put it down is marvellous. I was in contact with all those guys and I watched them constantly

The other thing that gets overlooked are some of the lyrical aspects which have a real sympathy and empathy with the working class – tracks like ‘Warpigs’, ‘Sabbath Bloody Sabbath’ and, to an extent, ‘Children Of The Grave’ spring to mind. Was that a case of, ‘You can take boy out of Birmingham…’?

BW: I think we were guys who were maturing a little bit and we were becoming more and more conscious of things that were going on around us. Maybe we were taking things much more seriously and kind of falling out of the bubble. Keep in mind that one of the most important things was that we were all, pretty much, pissed off guys. We were kind of at odds with the counter-culture. Some of those things: love and peace and serenity, that is what I crave these days! But back then, at 17 or 18 years old in Birmingham and coming from Aston, we didn’t care too much for peace, love and serenity. You had to watch your arse back then to make sure you got home safely and not get your fucking head kicked in.

I was angry about a lot of things. I’d look over the garden fence and I would see other things going on. All I know is, I went on into the blackness of where we lived and into the dark where the gas lamps still existed. The morbidity of that darkness reflected in my life, probably in some ways was a form of depression. But we were all angry young men and that really shows up in the music. Because we let our vulnerability be so pronounced in the music, it hit a chord with the people who listened to it. They were vulnerable and pissed off too.

That said, I think the counter-culture movement was very important and it was a very important aspect of youth growing up but some of the things that were attached to it, like wearing flowers in your hair, that wouldn’t have gone down very well in Aston. It might’ve worked in San Francisco but not necessarily in other parts of the world. We had that angry attitude and lyrically that’s where a lot of things began to stem from.

The leap from Master Of Reality to Vol. 4 is quite huge; it’s almost like you’ve skipped an album. How much did the change in environment and drugs of choice play a part?

BW: Yeah, you’re on the button there. Master Of Reality, I always felt, was the last album in terms of the constant touring. We went around the world multiple times and we played just about everywhere. We needed to take a break so we decided to make our next record in California and so some of the sunshine and some of the effects of that bled into Vol. 4.

And this included the aftermath of the counter-culture; there were still a lot of people still wearing flowers in their hair – and this is in 1972 – and that was still very prominent, especially in California. Geezer, Ozzy and myself even visited a lot of the hippy ranches and communes. We’d hang out there and we’d get high, man. They were all singing and banging tambourines.

A song came out of that. We went to Laguna Beach in southern California and we came back absolutely impressed. We must have looked changed to Tony but before too long ‘Laguna Sunrise’ appeared; he just wrote the song. And I thought, ‘Oh my God! That’s exactly what it was like.’ He’d just taken a musical photograph of it and he must’ve seen it in us when we got back. He’s a phenomenal songwriter; absolutely brilliant. And every time I play ‘Laguna Sunrise’, it’s smack on the money.

Things like that were a huge influence and by that time I was using cocaine and become addicted to it. I’m now in my 32nd year of being clean and sober but back then I was using a lot of cocaine on Vol. 4.

Black Sabbath recorded an incredible amount of music in a very short space of time on top of all the touring. Where the drink and drugs consumed a coping mechanism or the fruits of your labour?

BW: In hindsight, I can look back at my part of the story and see, though I didn’t realise it at the time, that I had alcoholic tendencies since I was a child. Had I played in the band or not played in the band, it would’ve been normal for me to have chosen any kind of medication or prescription drugs or alcohol, anything that I could get to numb me down and kill the pain of being alive. When you add alcohol to an alcoholic, I felt like I’d found God and a way of transporting myself across the universe.

All of that was going on and I think that it just fired the way that we were: a true rock & roll band of that time that immersed itself into a lot of drug and alcohol intake as well as playing very loud and aggressive music.

Tony Iommi once set you on fire and the rest of the band nearly killed you by covering you in gold paint. What kind of a strain does that put on relationships?

BW: I didn’t feel that there was any strain on the relationships at all until Oz left. He was having all sorts of problems, especially when his father passed away, but until then we were having a perfectly good time. I felt that everyone having a good time because I was having a good time. So through my eyes, because I was having such a good time, I wasn’t really aware that there were problems. I only noticed the first problem when Oz didn’t show up for rehearsals and he actually left the band and I’m really grey on that. He left for a short while and then he came back, thank God.

Then I recognised we had another huge problem when we finished Never Say Die and we wanted to move on to another album and of course that was when Oz was asked to leave.

Why did it fall to you to tell Ozzy he was fired?

BW: Because I usually had to clean up all the shit. I’m like the fucking janitor in that band. Most of the time I always got the shit jobs that nobody wanted to do. I don’t do that anymore. I recognised I was co-dependent as well as being an alcoholic so I don’t do shit like that anymore. But Oz was like a brother. He still is today but I don’t talk to him right now. It’s not like I don’t love him or anything.

But at the time, I thought maybe I was the best guy to do it. I kind of volunteered to do it: up went my hand and it was one of the worst things I’ve ever done in my life, to be honest with you. I didn’t want him to leave the band but I could understand the reasons why but yeah, that was a tragic day. That was the day the band imploded.

You sang lead vocals on ‘It’s Alright’. What was it like stepping behind the mic?

BW: Well, I’d done that a year before and I’d done it as a party piece. Ozzy really liked that song. When he’d have some songs he’d play them to me and say, ‘What do you think?’ I’d say, ‘That’s fucking great – we should record that!’ So he really liked ‘It’s Alright’ and he said, ‘You really need to record that.’ We were in Criteria Studio in Florida recording Technical Ecstasy and I guess we were a song down so we just threw that together.

And I asked Oz if he was OK with it and he was like, ‘Yeah, fine, no problems…’

Why did you quit the second line up with Ronnie James Dio?

BW: The alcohol was, without question, the robber of everything. Alcohol had become more important than Black Sabbath, our audience, my family, everything and that included me. I crossed the line.

We talked about it in recovery and we called it ‘The Invisible Line’ and I crossed that invisible line when I lost control in Minneapolis. I blew a gig we were supposed to be playing and I literally placed more priority on the drink than I did the gig. That’s about the worst fucking crime anybody can commit [in rock & roll]. I’ve lived in sorrowful amends about it since it happened. Part of my life today is ensuring that will never happen again. I want to lead a new life and I never want to experience anything like that again. It was absolutely terrible.

That’s one of the reasons. Also, I was absolutely missing Oz; really missing him and I wasn’t coping with my grief that well because I was so drunk. My mother had died and I wasn’t coping with the grief for my mother and I was feeling overwhelmed with loss.

Lastly, as much as I loved Ronnie James Dio, it didn’t work for me. It didn’t jive properly, especially when we were doing old Sabbath stuff. It worked when Ozzy sang it but when anybody else tried to sing old Sabbath stuff then it didn’t work. It’s exactly the same when Black Sabbath go out on the road now with other drummers: it doesn’t work. I’m not saying that to be rude or anything but it doesn’t fucking work; it doesn’t sound the same.

The original line-up reformed several times but the announcement in 2012 said that you were all ready to play and record together again but it ended up not involving you. There were all sorts of stories about your health and the nature of the contract that was offered to you. Can you talk me through what happened?

BW: It certainly wasn’t about my health. Had I signed the contract there wouldn’t have been a health problem. Ozzy made a lot of statements in 2011 saying that my health was poor and it wasn’t, and I’ve made a lot of statements about that and I’ll argue that now until the day I die or he dies so that’s going to be ongoing. It wasn’t about my health.

We started to negotiate a contract in the early part of 2011 and during that time I was in rehearsals, on time, every day, working with the band putting things together for what would be the album. I was there showing up and I did all of that kind of stuff. When I knew we were going out to play on tour, I started to train up and get into a touring readiness because there’s a difference in being fit for touring and being able to record. To have been able to tour I’d have needed to have dropped off some weight – about 25 pounds – and I do that all the time. They know that and they know that I always drop off weight before touring. So I did all my stuff [to lose weight] and put some things together that I thought might work and we continued through every single day to negotiate the contract and what they were offering me was not what I wanted.

Because of the previous contract from previous tours, I had reached the point where I said, ‘I’m not going to sign into any more bad contracts’ and so we were trying to negotiate a respectable contract and we did it through the entire length of 2011. In January 2012 we received a letter from their management saying that they couldn’t negotiate any further and not to bother coming over to England to continue working with Black Sabbath. That was at the time that Tony had become quite ill and I went, ‘Well, that’s it, then.’

I still continued to try to find a way of getting on board with the band but that didn’t happen. There was a very cold response on their part for me. Ozzy kept calling me in late January saying, ‘When are you going to come over?’ and he wanted me in the band. Of course, that doesn’t reflect on his story about me being such a, y’know, and that really annoys me. He wrote a lot of stuff about what I was like in 2011 and he started the health problem story which literally has been like a fucking fire across the universe and has been really unpalatable. So he’s on the phone in January of 2012 going, ‘When are you going to come over? We need you to come over’ and I couldn’t come over. My hands were tied.

One thing that we did do: there were some concerts that had already been arranged and so what we did was that we sent a letter to Sabbath’s legal department saying, ‘Can you please delete my name and likeness from the [gig] posters that you are advertising for those gigs?’ The reason we asked for that was because we didn’t want the fans to think that I was going to be playing because I knew that the contract had fallen to pieces. The outcome of that request, by the way, is that they’ve deleted all of my pictures from all of the photographs that ever existed which I think is one of the shittiest, most vindictive actions that’s ever happened in rock & roll. I think I’m still on the albums but that surprises me that I’m still on albums, but they’ve deleted my name and likeness from every press photo about Black Sabbath. And that still continues to go on today. I’d only asked for my name and likeness to be deleted from the advertising of those concerts and not the entire back catalogue. And the whole world believes I requested that because that’s what they told them.

Someone in their camp, a spokeswoman, said, ‘Well, Bill requested that we take down his name and likeness’ but she didn’t say that that was pertinent to three concerts only. The said it was Bill’s fault and we’re only doing what Bill asked. And I hate the way they turn things around to be in their favour and make me look like the bad guy, and it’s created a huge, huge amount of animosity.

You all recently got together at the Ivor Novello awards. At the risk of sounding naïve or like Jeremy Kyle, is there no way those four lads who jammed together in the Aston Community Centre can sit in a room and sort this out among themselves?

BW: I’ve been really clear and I’ve made press statements about what I need. I love the guys and I really miss playing in Black Sabbath but I’m really clear about what I need. I need Ozzy to amend the statements that he made about me, which were completely untrue, and I need a respectable, signable contract, which is what we were working for in 2011. If we can achieve those things then yours truly will hopefully be back in Black Sabbath.

Am I correct in assuming that you’re looking for a four-way split?

BW: No, I’m not even looking for that; nothing like that. I’m just looking for my name and likeness to be considered. I’d like for some publishing to be considered and I’d like to have a decent fee for playing live on stage. I can’t go into numbers but what they were offering me was very, very low. When I’m onstage, I’m a member of the band and I expect just the same. I’ve put in the same amount of work but this has been going on for several tours prior to this.

Playing Devil’s advocate here, Colonel Tom Parker once said words to the effect that a percentage split of something is better than a percentage split of nothing.

BW: Well, I wouldn’t want to disagree with the Colonel but when you know that your self-esteem is becoming more and more healthier and you recognise what you’re playing for and what you’re being given, knowing what you’ve done in the band and what you are historically to the band then all that has to be considered.

The kind of fees that I was picking up were, on some occasions, slightly less than what some of the road managers were getting. And that’s nothing to do with me saying that road managers are unworthy – I fucking love the roadies; they’re the salt of the earth – but those were some of the figures I was picking up and it was becoming intolerable and it was like, fuck! I was coming home broke after those tours.

One last question: what do you think is the biggest misconception about Bill Ward?

BW: Right now, everybody thinks I ought to stop squabbling and just go out and play and get it on. But behind that there’s a person, a real human being who bottomed out at the end of 2005 on the last tour that I did with Sabbath saying, ‘I can’t go on like this anymore. It’s killing me.’ If the people who find criticism in me had to walk one mile in my shoes then they’d turn round and say, ‘Holy fucking shit, man!’

I’m just trying to stand up for myself and get what I ought to have and deserve.

Accountable Beasts by Bill Ward is out now on Aston Cross Records