Imagine a record label that turned down Joy Division. Imagine if that record label had already turned down The Cramps. Now imagine a feature-length documentary charting the wayward history of Scottish indie music that doesn’t mention Glasgow until some thirty-eight minutes in.

Such expectation-confounding contradictions are the driving forces behind Big Gold Dream: Scottish Post Punk and Infiltrating the Mainstream 1977-82, Grant McPhee’s new meticulously sourced filmic dissection of Edinburgh’s world-changing post-punk scene which has its world première this weekend at Edinburgh International Film Festival.

Ten years in the making, Big Gold Dream charts the legacy of Bob Last and Hilary Morrison’s short-lived Fast Product label, which put out the first records by The Mekons, Gang of Four, The Human League and The Dead Kennedys, as well as Edinburgh’s original post-punks, Scars. With only occasional diversions to Glasgow, where Alan Horne founded Postcard Records to release singles by Orange Juice, Aztec Camera, The Go-Betweens and Edinburgh’s Josef K, McPhee’s film provides the missing links in Scotland’s much mythologised pop history.

“Every city seemed to have important record labels,” McPhee says, “but I think it’s unfair that Edinburgh and Fast Product never seems to get the attention it deserves. I think it’s a shame if people have never heard the music the label put out, but I think Fast probably got a bit of a hard time because of the way they did things. Up until then most records came out in plain covers, but the way they packaged their records and played with consumerism, I think people were probably a bit scared of them. Also, Indie music as we know it didn’t exist at that time,” McPhee points out. “It wasn’t a genre. It was a means of releasing a record. ”

Inspired by the Buzzcocks EP, Spiral Scratch, released on the Manchester-based New Hormones label, Last and Morrison founded Fast Product as a concept as much as a record label. They made crucial play of each release’s packaging, so every record was effectively several works of art in one. This was especially noticeable on the label’s trio of Earcom compilations, with three or four bands donating a couple of tracks apiece in a way that was designed to be heard as an audio magazine.

While marrying ideas, image and audio is commonplace now, then such a conceit was a radical post-modern gesture that was a huge influence on labels that followed, including Alan Horne’s Glasgow-based Postcard Records, and especially on Tony Wilson’s Factory Records. As Last says in the film, Fast only put twelve records out, but if there had been a Fast 13 it would be Factory.

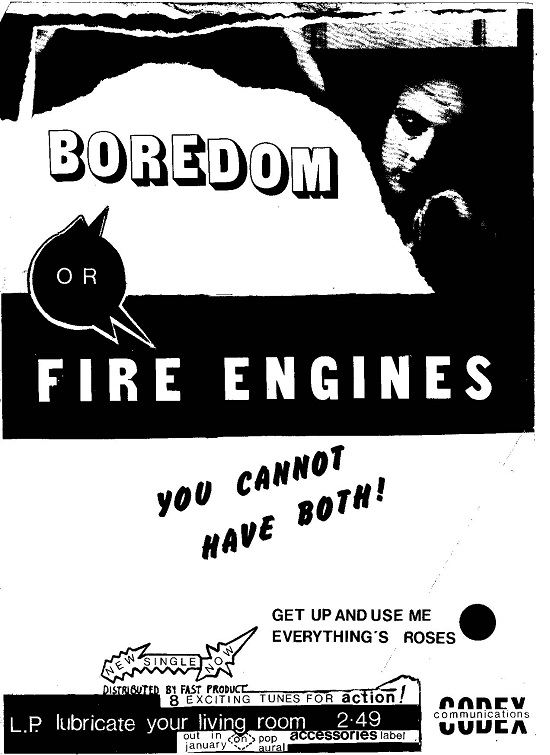

Last and Morrison followed Fast Product with the infinitely glossier Pop Aural label, releasing two singles by Morrison’s band The Flowers as well as other Scottish acts including Boots For Dancing, Restricted Code and former Rezillos guitarist Jo Callis. Pop Aural also released two singles by Fire Engines, ‘Candyskin’ and the label’s swansong which gives Big Gold Dream its title.

By November 1981 when the 12” single of ‘Big Gold Dream’ came out, Last had drafted Callis into The Human League, who he was now managing, and whose third album, Dare, was about to go stratospheric, while the accompanying single, ‘Don’t You Want Me’, co-written by Callis, topped the charts over Christmas 1981. Things had come a long way from the tenement flat beside Edinburgh College of Art where Last and Morrison dreamt up Fast Product.

“They did it,” says McPhee. “Bob Last and Hilary Morrison drafted this manifesto or mission statement before they’d even put out a record, and getting the Human League a number one single and a number one album was all part of the same master-plan, and they’d done all that from an Edinburgh flat. Joy Division had very much wanted to sign for Fast, and in the end they gave them two tracks which were on Earcom 2, but the quality control was so high that they turned them down, and they turned down The Cramps, who’d sent them a cassette of ‘Human Fly’.”

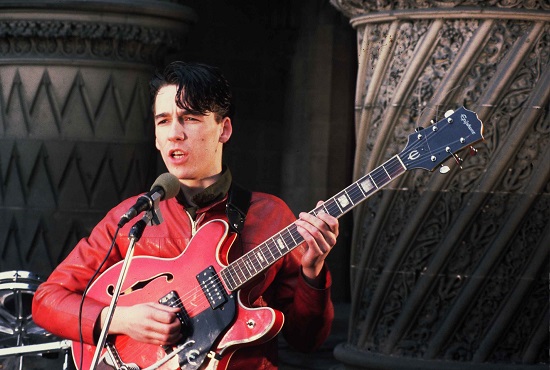

Joy Division and New Order bassist Peter Hook confirms his band’s fondness for Fast Product during his appearance in Big Gold Dream. As the film also makes clear through interviews with the likes of Fire Engines front-man Davy Henderson, Scars singer Robert King, Josef K guitarist Malcolm Ross and Last and Morrison themselves, many of the bands associated with Fast Product had been kick-started into life by The Clash’s White Riot Tour. With ‘punk’ gigs banned in Glasgow, the tour arrived at Edinburgh Playhouse on May 7th 1977. It wasn’t the head-liners, however, who provided the inspiration, but support acts The Slits and Subway Sect.

While Edinburgh’s punk-inspired live scene thrived in venues such as the Tap O’Lauriston, situated a stone’s throw from Last and Morrison’s flat which had become a kind of tenement version of Andy Warhol’s Factory, it would take until 1979 for a local band to release a record as iconoclastic as their forbears. This came in the form of Scars’ début single, ‘Adult/ery’ backed with the Clockwork Orange inspired ‘Horrorshow’, which in Big Gold Dream Douglas MacIntyre, bass player with Fire Engine Davy Henderson’s latest vehicle The Sexual Objects and head honcho of the Fast inspired Creeping Bent record label, identifies as Scotland’s equivalent of the Sex Pistols’ ‘Anarchy In The UK’.

“It was such an important record,” says McPhee of the Scars single that was later sampled by Lemon Jelly for their piece, ‘The Shouty Track’. “That seemed to change everything.”

With a background as a TV camera operator, McPhee never had any ambitions to be a film director. While doing some video production work for Mani Shoniwa, who had played with Henderson in his glossy post Fire Engines pop project, Win, McPhee was asked by Shoniwa if he could make a documentary film what would his ideal subject be.

“I said I’d make it about Postcard Records,” McPhee remembers, “and before I’d had time to think about it he rang Malcolm Ross. Then I spoke to Malcolm, and he said I should speak to Scars, who I’d never heard of at the time, and that led me to Fire Engines and Josef K and everything else. I moved to Edinburgh in 1999, and for me then, all the music in Scotland I knew about was from Glasgow, so finding out about what had gone on in Edinburgh was really interesting.”

With no backers behind him, McPhee interviewed people on the hoof when he could, financing filming himself before eventually hooking up with co- producers Wendy Griffin, Innes Reekie, Erik Sandberg (who also plays with Creeping Bent related band Wake The President), and Angela Slaven.

With more than seventy hours of interviews recorded, the complex web Big Gold Dream weaves could feasibly be stretched out over a ten-part TV series. As it is, Big Gold Dream is the first of two films by McPhee charting the history of Scotland’s music scenes. The second, Songs From Northern Britain: The Country That Invented Indie Music, moves further west as it charts the rise of the likes of The Pastels, The Jesus And Mary Chain, Teenage Fanclub and beyond.

As a body of work, both films provide vital documents of Scotland’s musical history in a way that previous films on the subject have not. Where previously history has been rewritten by lumping glossy chart acts in with Postcard and Fast Product progeny, Big Gold Dream reclaims a sprawling history to finally give its unsung heroes a voice.

“I was chasing people all over the country to get interviews,” says McPhee of the seventy hours of footage he has amassed. “I love music and I love finding out about music, so it was a pleasure to be able to talk with all these people and sate my geeky thirst for knowledge. A lot of people hadn’t spoken about that time and initially didn’t want to talk, but after eight years or something they eventually decided that they would.”

While most of the scene’s main players feature in new interviews, as well as words from Creation Records founder Alan McGee and former NME post-punk champion Paul Morley, there are noticeable absences. Josef K front-man Paul Haig chose to be interviewed in audio only, while Aztec Camera mainstay Roddy Frame isn’t interviewed at all, leaving bass player Campbell Owens to fill in the gaps.

Edwyn Collins was presumably and understandably too busy with The Possibilities Are Endless, James Hall and Edward Lovelace’s moving 2014 film about the former Orange Juice singer’s life and work since suffering two cerebral haemorrhages, to take part. It is the lack of new footage of Postcard svengali Alan Horne, however, that effectively makes this Last, Morrison and Fast Product’s film.

Narrated by Robert Forster of The Go-Betweens, Big Gold Dream: Scottish Post Punk and Infiltrating the Mainstream 1977-82 looks set to receive a limited cinema release later this year, with a TV screening mooted at some point. Clearly a labour of love, McPhee has pulled the film together with a similar spirit to the one that fired Fast Product. It’s significant too, perhaps that Bob Last has gone on to become a film producer of note who, alongside co-producer Roy Boulter, former drummer with Liverpool band The Farm, is currently behind Terence Davies’ forthcoming big screen adaptation of Lewis Grassic Gibbon’s novel, Sunset Song.

“There’s going to be lots of film-makers like me,” says McPhee,”who I think should start making features in the way that Bob and Hilary and Alan Horne started record labels. Things have changed radically over the last ten years in terms of cameras and technology, and things are much more accessible now.”

McPhee’s seizing of the means of production over the last decade is one thing, but much has changed too in how the era he focuses on has been reassessed. While Franz Ferdinand had started to name-check Josef K and Fire Engines as influences when they started out, going as far as covering Fire Engines’ song, ‘Get Up and Use Me’, with a briefly reformed Fire Engines sharing a single with their progeny with a version of Franz’s ‘Jacqueline’, much of Fast Product and Pop Aural’s adventures with art and commerce remain barely acknowledged. Big Gold Dream looks set to change all that.

“Fast Product and Edinburgh have been very unfairly treated in terms of its musical significance,” says McPhee. “At the time I started working on the film Domino Records hadn’t released the Fire Engines compilation, and if you read books about that time Fast Product only seemed to be a footnote before things moved onto something else, but it was much more important than that. This is stuff that should be taught in schools, and in art schools especially. Fast Product wasn’t just a record label. It was a concept. I admit I don’t completely understand it, but it was art in itself.”

Big Gold Dream is showing at the Edinburgh Film Festival tonight. For more information see the festival website here