When I mentioned to other journalists that I had this interview with Kim Gordon coming up, a lot of them told me she was a tough gig. Even those who hadn’t spoken to her themselves relayed accounts: Kim Gordon is famously reticent; she hates being asked anything; she’ll tell you how little she wants to be there. As a Sonic Youth fan – let alone as someone who’d have to write up whatever happened – I was nervous.

So let me set the record straight, for future writers: Kim Gordon is not tough to interview. I have interviewed difficult subjects – people who are outright hostile to being questioned, or become angry if you ask them something they feel is outside the interview’s purview. (Incidentally, no-one warned me about these writers, who are men.) True, Gordon is obviously an introvert who takes no pleasure in doing publicity, accepting the extroversion of her job only as a necessary tax on being an artist. But she is all the things that make working with someone enjoyable: kind, polite, funny and very, very smart. Reticent as she is when talking about her own life and motivations, she opens up when the subject shifts to art – a far preferable state of affairs to the reverse. At one point in our interview, we sat in silence for some minutes while she looked up the date of a particular ballet on her phone.

Kim Gordon has her priorities in order.

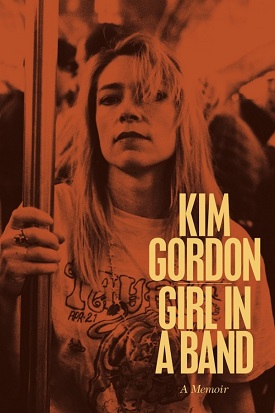

Since the release of her memoir Girl In A Band, she’s done a lot of interviews. Gordon appeared on Women’s Hour on BBC Radio 4 with Caitlin Moran, where she was asked about her current music taste (and was forced to admit she doesn’t keep up with mainstream music). She invited the New Yorker into her home – Alex Halberstadt also seemed not to mind her uncompromising manner. Sometimes, it feels like every media outlet has asked her about Thurston Moore.

I can’t understand why. Actually, that’s a lie; I understand good copy as well as anyone else. But if you have Kim Gordon in front of you, it seems remiss to ask about her private life when you could be asking about her artistic process. (For the record, the pedal she likes the most right now is a kind of Hendrix optic fuzz, although she’s not played bass for a while.) In the London Review Of Books, Kristen Dombek ends her Girl In A Band review by vocalising a question she intuits unspoken in the text: “if you wanted this book to be about a life destroyed, why?”. As I left the Foyles office where I met Gordon, I found myself silently asking the press who have complained about her a similar question: “if you find Kim Gordon frustrating to deal with, why?”

I love that you start with this moment headed “the end” – what made you decide this is the moment to write it?

Kim Gordon: Um, well, other people were starting to ask. I… yeah, it was just sort of looking back over my life, it seemed like a good time to figure out how I got to where I am. Writing is a good way for me to figure out how I’m feeling, or thinking about something.

It was hard to find a way to talk about Sonic Youth because there’s so much there to talk about, and I didn’t want to write a book about Sonic Youth; so I tried to make little essays around certain songs, and then pitch it around different things going on.

It’s weird doing an autobiography, of course, because you go on living after…

KG: Right! I don’t know. It’s weird, because one of the things that helped me be able to write about it was to not actually have to think about… doing interviews [laughs]. It’s more about a process: it’s something creative to do. I don’t really want to deal with talking about it.

You work across so many different mediums – I guess the autobiography is a separate thing. More generally, what’s your creative process like? Is it free-flowing, intuitive?

KG: It’s pretty structured. I mean, if I’m in my arts studio I’m thinking about artwork. It’s not as free-flowing as, say, one thing leading me in one direction, or one thing leading me to another; it’s more like certain ideas are part of something. But you know, occasionally ideas will enter into something else – lyrics that I’m thinking about will end up in other work.

Sometimes I will start writing as a process of thinking about ideas for an art show. And, yeah, I can sometimes only think if I’m writing. I mean, not entirely, but… I’ll write and go: “Oh, who is that!”

How do you know when something’s finished? In a way the hardest bit is giving something away.

KG: I don’t know – it’s different for each thing. Sometimes you get ideas as you’re installing something; the installation is another aspect to the work. Or you get sick of working on it.

With the book, I didn’t want to overthink it, or become overly precious about it, about what is or isn’t in it. I kind of wanted to just do it. And it’s not the “stamp” of my whole life; it’s a story.

Were there any stories that didn’t fit the narrative that you wish you could have fitted in?

KG: No, I mean, there’s certain things I wish I could have articulated better… I didn’t want to think of more things to put in. Although, actually, that happened: I was talking to a friend and he was like “did you put in that story about Henry Rollins?” and I was like oh, shoot. I had to go back and put it in again.

I guess I wish I’d been more articulate about the Lana Del Rey stuff. The version that went out was not even in my book. I was being lazy about articulating the difference between persona and what a person is: their image, their brand, whatever.

I read that Guardian interview of hers, though, and it was definitely a thoughtless interview.

KG: Yeah… I didn’t actually read that. I saw it out of context, I saw Frances Bean Cobain reacting to it.

I was thinking, oh, she’s really taking her seriously, because she thinks that’s really who she is. She doesn’t realise that’s just Lana Del Rey’s image, she’s just saying it.

But that’s been taken out of the book by everyone: this one thing.

KG: I know. I mean, it’s so little in my book, and I didn’t even say that in the final version. And that thing about feminism: again, it was taken out of context, but her saying “doesn’t feminism mean you can do whatever you want?” – I don’t actually think that’s what feminism means. You have to have a moral boundary. You can’t kill someone! It’s not a licence to have no responsibility about what you do.

And not everything is about feminism, but I realise that celebrities get tricked into this feminist question. People get tricked into a lot of questions, or things get blown out of proportion, or plucked out of context. I shouldn’t have reacted in that way. But I felt protective of Frances; I was being reactive, in a way.

But it is kind of infuriating, the media coverage of female celebrities. And artists use “feminism” as branding, without actually changing what they’re doing.

KG: Right. Yeah. It’s just… it is really about equal rights and equal pay, regardless of what’s going on.

It’s economic.

KG: Yes! Also: why are people so excited to see women in a catfight? Still? Like that’s the most important thing.

Nobody went through your book and went, “Danny Elfman’s a big deal!”

KG: At least they weren’t talking about my marriage. But there were so many headlines. It’s annoying.

What about your latest project, Body/Head? Do Sonic Youth fans say anything about the change of direction?

KG: I don’t think most people at this point do. At least, live they didn’t – or they didn’t seem to. They were respectful. By the time the album came out, they were used to the idea.

Is it nice to get to a more pared down form?

KG: It’s nice just playing with one other person. It’s kind of like back to basics: how much you can do with two people.

The music scene today is different, too. You have that wonderful line in the book where you ask “did the 90s even really happen?”. How do you think we’ll look back on today’s scene?

KG: A lot of artists on Soundcloud, in the ether. Before people are putting out CDs, they’re putting out things on Soundcloud. I don’t really pay that much attention to the music world right now.

But the venues and cities, even, are different: London and New York have changed a lot.

KG: I guess so. I don’t really go out. Not that much, to clubs, y’know, in New York. I don’t live in New York. It seems like there’s more money in NY – real estate’s changed.

What about the arts? What’s interesting you right now?

KG: I like this artist Nick Mauss — he’s got shows at the same gallery as me in New York. I was here in London last fall doing collaboration with him on this ballet during Frieze. It was inspired by a ballet that Njinsky’s sister wrote, a gossipy salon ballet. Actually, at the time, it was considered the first avant-garde ballet.

It was deconstructed. Mauss worked with the Northern Ballet Company and this woman, a choreographer, who used to work with Michael Clarke. There was something going on all day long. Julian Huxtable also wrote a text; we both wrote a text, and played music at different times. That was really fun: we improvised, the dancers improvised, and that was great – to see the dancers improvise. I think it was… early 1920s? [She looks it up on her phone] 1924.

How does it compare to a club, or another venue where people are there to see you? Do you like those more incidental spaces?

KG: Well, that was an unusual situation, because people are just wandering in and don’t know what’s going on. I mean, it was four or five days – by the end people were more informed about it and knew what it was.

But, actually, the first day this irate booth owner, gallerist, came storming over – just, actually, as I was ending, but it seemed like she’d cut me off. She was this woman with bright red hair, and she was like: this cannot happen! I paid thousands of dollars! You’re interrupting my art sales!

But it was the Frieze people who commissioned it, so there wasn’t much she could do. It was funny timing.

You seem to be very interested in what compels female performers to perform. Do you still feel male and female performers come to rock with different motivations?

KG: I don’t know… I hate to generalise. For great and lesser degrees, they do it because they’re seeking attention. Whether or not they’re an out and out exhibitionist is another question.

I went to see the David Bowie exhibit, and it starts out with his writings, talking about how he never thought about being a performer; I thought that was really interesting because he was such a performer. I don’t know enough about him to untangle that.

And, you know, there are a lot of shy people who end up being performers. It’s not surprising to me, because I tend to be more introverted, but some people are better at being out in the world as “personalities” or something like that. They really thrive on doing interviews and things. But I don’t relate to that as much.

Have you got used to it yet?

KG: I hate it! I find that that then becomes hard to move around in the world and do different things, if people think of you as a “personality”.

You sacrifice that malleability?

KG: Yeah.

Girl In A Band is out now, published by Faber & Faber