Once inaccurately described by The Guardian as the definitive ‘gentleman monomaniac’ of the British counterculture, genius savant Billy Childish is in fact distinguished by his omnivorous, multifaceted approach to his work. It’s an oeuvre which, to date, has produced hundreds of records of punk, rock & roll,blues, spoken word, nursery rhymes and garage rock via his litany of bands and musical projects (including the Pop Rivets, The Milkshakes, Thee Mighty Caesars, Thee Headcoats, The Buff Medways and Wild Billy Childish And The Musicians Of The British Empire – latterly morphed into CTMF), thousands of paintings, sketches and woodcuts, collections of poetry, artistic treatises and a slew of autobiographical and experimental novels (including My Fault, Notebooks Of A Naked Youth and Sex Crimes Of The Futcher). Childish is also responsible for of countless incarnations of esoterica, including the Short Sunderland door-knocker, the Dazzlelac guitar and home-made guns discussed in our interview below.

Childish has forayed too into the realm of experimental film, and collided repeatedly with the high-end art world represented in part by (now-not-so) ‘Young British Artists’ with increasing penetration, success and recognition – Childish arguably now has a better reputation among the more critically astute. Beleaguered throughout his career by dubious summations and categorisations advanced by bewildered critics, Childish has remained defiantly obtuse and uncategorisable.

Childish has chosen 10 artefacts from his long and hugely eclectic career as a way in to familiarity with what may appear to be an intimidating corpus. He is a true raconteur – very funny, very sharp, and eloquent about the connections and contexts which have informed his work for more than 40 years. It’s intriguing, impressive stuff, and it maps out the contours of a life lived with unusual fire, perspicacity and innovation.

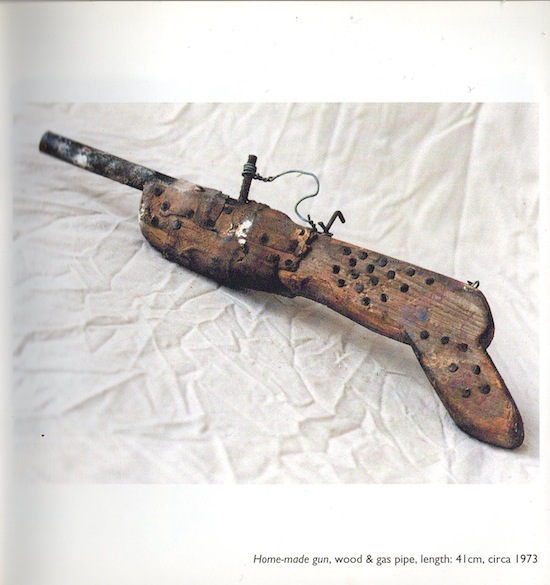

1. Home-Made Gun (1973)

My schoolfriend Goldfish and I used to make these guns. I’d known Goldfish since I was about four, and we became thick when I was about 13. He was really into making weapons. He’d read up about all sorts of strange ideas – nitroglycerine and all sorts of more dangerous stuff which involved him trying to get hold of sulphuric acid.

We had a strange thing going on at the time: we formed this military research group – called the ‘Medway Military Research Group’ [MMRG] – and we used to go round studying and surveying the local forts around Chatham. We published a little guidebook. We’d go and break into the local forts – the Napoleonic and the Palmerston’s Folly forts around here [Medway]. We also had a more ‘active’ wing [of the MMRG] called ‘The Walderslade Liberation Army’ [WLA], which was basically formed with one goal in mind – to stop people building on the woods that we played in.

The WLA dug an underground bunker in the woods, where we kept our armaments: we had a sten-gun that we’d dug up in a field and 303 Lee Enfield rifles adapted to take 410 cartridges – you used to be able to buy them from Exchange & Mart. Then we would make these guns by bending a metal pipe, drilling a hole in them and then using red matches and a screw as a firing pin. We used to go to the local Boots in Chatham, and buy the ingredients to make black powder – before restrictions brought in because of the IRA, buying these ingredients was easier than it would have been 10 years later. But there used to be some difficulty in buying the saltpetre. We had the reason why we were buying this stuff ready for the chemist, and that was that we were dusting our mothers’ dahlias – it used to be used for that – so the people in Boots used to ask why I was buying saltpetre, and I’d say, "It’s to dust my mother’s dahlias."

Saltpetre is the oxygeniser of black powder, so that was the one that raised the eyebrows. Of course the thing to do was not to go into one shop and ask for all three ingredients – we’d go to different chemists. So then we used to grind up the black powder and fill the gun with it (and we never had a big disaster with that, luckily). We’d put old split-shot [fishing weights] in one end – on top, with a plug of clay – and then drill a touch-hole and put a screw in the top, before hitting it with a hammer.

The guns did fire, although it was difficult and there was a lot of misfiring. You had to put them against a surface and then whack them. You can’t load them up quick or anything; it’s actually quite a painstaking process getting them to work, and then they don’t! My brother nearly came a cropper – we had one gun that wouldn’t work, my brother whacked it and the thing exploded. Later on we were walking down to the shop and we found the screw that’d flown off and gone past his ear – like a bullet – a couple of hundred yards down the road. It was all blackened.

I’ve still got one of the guns. I think it’s legal: although you can actually fire it, it’s ultimately just a piece of metal with a hole drilled in it. But I don’t actually have any black powder anymore – just so anyone out there knows.

As well as being in the MMRG and the WLA, I was also part of the Upchurch Archaeological Group [UAG]. We used to go out digging on the mudflats, on the old Roman kilns. My friend Ian was in charge of the UAG – we were both fascinated with history, particularly the story of the Belgicks, a Gaulish tribe who came over to Kent and were displaced by the Romans. The Belgicks were very good at decoration and art. And Ian said there was a big correlation between tribes with high levels of warrior-like tendencies and the quality of their art. I was excited by that.

I was around 13 or 14 years old when we made the guns. I didn’t think of them as pieces of art at the time; if they ‘look like’ a piece of art, it’s because I’m an aesthetic type of person – it’s in my nature to be like that. I would be much more famous – and richer – if I declared that things like my homemade gun are ‘art’. People like that: they like the idea that the declaration is the thing that defines what something is. I disagree with that quite strongly – I refuse to go down that road. I don’t call my poetry ‘art’. I don’t call my photography ‘art’. I like things to have their normal name.

I’ve always made things – ever since I was a young boy I have made things. And there’s lots of things I didn’t keep, but I kept some, and I liked fetishising those things. That’s a term I never would have known about before, but I understand now that that’s the truth of what I get up to, with objects.

Like I said – we used to build underground camps in the woods that you could just about get into. A bulldozer actually fell into one of our bunkers – we weren’t in it at the time – and ended up with one track sunk into the ground and the other one spinning free. This was one part of the focus of our campaign – we were against the developers. That campaign was quite sustained and a little bit illegal. What they called vandalism we called resistance. We were sugaring the engines of their bulldozers, destroying their stake-outs, daubing ‘WLA’ in green paint over their vehicles and then we’d go out there in the morning and none of their stuff would start. The workmen would say to us: "Do you know what WLA stands for?" And we’d say, "‘ I dunno – Woman’s Land Army?"

Not all kids were like us, we were quite strange. Goldfish and I were the oddest of the kids around because we would do these kind of things. They weren’t the normal things to do. We didn’t go to football or things like that.

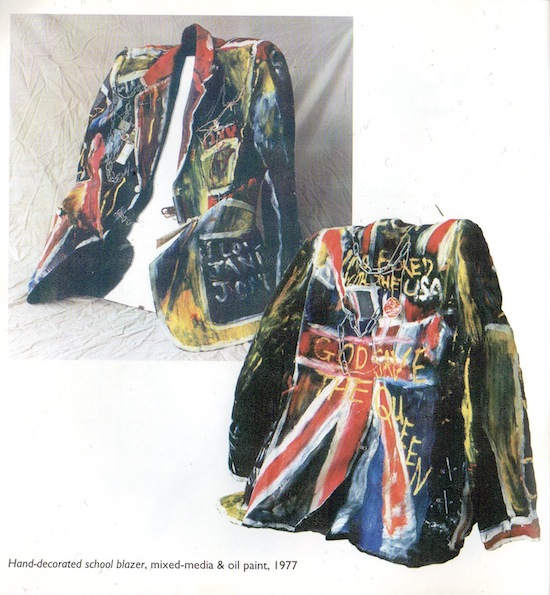

2. School Blazer (1977)

That was my brother’s blazer, but I was using it because I needed a jacket to paint and my brother hadn’t been wearing it for seven years. It’s not a ‘homage’ to punk – It was made in 1977 so it IS punk! In the spring of ’77 I was wholesale for punk. For six months, I though it was the most fantastic thing – punk rock was the great liberation of my life. I was someone who wasn’t allowed to sing in school because I’m tone-deaf – so all this music was just permission to do everything. It was the same as reading Bukowski when I was 21 – it was permission to do everything. Punk rock meant I was allowed, it said, "You’re included" where everyone else said, "You’re excluded." The only reason I used to sing in a punk rock group was that I was one of the only punk rockers in town.

I used to go out in this. I’m not sure if I ever wore it at our gigs but I’ve still got some other stuff that goes with it, trousers and shirts. It was done in the summer of 1977 – it’s not these new romantic Brit artists looking back at something, this is frontline troops! This is the British Expeditionary Force 1914, this is the real thing! I was a punk rocker!

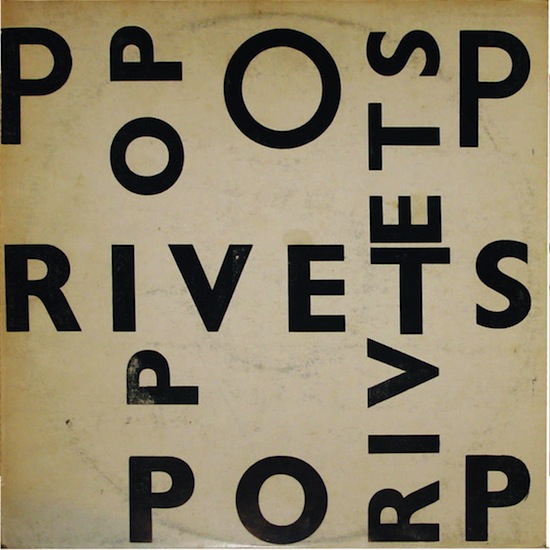

3. Pop Rivets Home-Made Sleeves (1977)

This was the artwork for the first album of my first band – we did the sleeves ourselves and with real style. The Pop Rivets weren’t ‘rejecting’ punk rock, that isn’t quite right. We largely gave up on it by the end of 1977, but we WERE a punk rock group. We gave up because of Sham 69 and it getting a bit funny and violent at the gigs. The skinhead thing was a factor. I saw The Clash at The Rainbow I think at the end of 1977. Sham 69 were the support, and it was all a bit unpleasant. The skinheads started turning up and then it was only six months later that you had identikit punks turning up – skinheads, mohawks, leather jackets, that kind of thing. The Pop Rivets were still punk rockers but we were old-school – we were Oxfam punk. By that time we were dressing more like mods anyway because that’s what they had in the Oxfam shop and that’s what we liked!

My theory is that punk really lived in the suburbs, the provinces. We believed the lie pedalled by Malcolm McLaren – that you could do it yourself – so it became real. We did do it ourselves and we made it happen. It became real because you believed the propaganda.

This is the strange thing about where punk rock comes from. My pre-punk listening originated from a totally different background from the other punks. They were secret glam fans, but we were rock & roll fans. I was brought up listening to rock & roll. My interest was The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. The reason why punk rock went bad really fast is because they were all really glam rockers. They were all fans of that glam music. I thought punk rock was a rock & roll revival of rock & roll, not just about the style.

This is why that stuff could re-emerge so easily out of punk rock – it became new romanticism. Prior to punk rock I was listening to Bill Haley, Gene Vincent, The Rolling Stones and The Beatles live at the Hollywood Bowl. I wanted elemental rock & roll music. I did NOT want Ziggy Stardust. Most of [the punks] were really closet Bowie fans. And while I don’t have anything against Bowie, he really wasn’t for me – I just didn’t like the glam thing. I saw some of those groups when I was 12 or 13, like Slade and Roy Wood, but I used to go to the rock & roll revival shows mainly – which were really useless because I wanted The Beatles in ’62 or the Stones in ’64. I wanted everything pre-rock. And that’s what I’m interested in now. I don’t like rock music. I used to get in trouble at school because I didn’t like music. For me, it was a rock & roll question, and it’s always remained that. The thing is, David Bowie when he was with Mick Ronson, he would do an impersonation of rock & roll, and he’s got an alright voice, and he was alright at ripping off R&B, but he’s still not as good as the real thing. And it never was the real thing because David Bowie wanted one thing more than anything else on this planet – which he got – and that was to be famous. I watched a BBC documentary about him a few years ago, it was fascinating. David Bowie was someone who wanted to be famous! He was talented and charismatic but that’s beside the point: there are lots of people who are talented and charismatic but who don’t have such an obvious desire for fame.

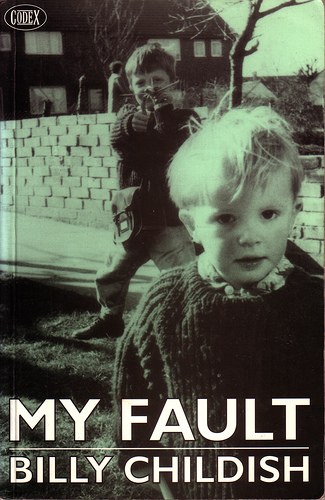

4. My Fault (1996)

It took me something like 15 years to write My Fault. In a lot of art and literature there’s this idea that the artist ‘deals with’ things that have happened to them, when mostly they really don’t. But in terms of My Fault, it was kind of like that. I had a lot of demons to deal with from my past. I think I’d almost been led to believe that my life didn’t happen, that these things never happened. And because I was talking about sexual abuse and all that – if I’d whined at the right pitch, or played the victim, I would have probably earned a lot of accolades. But because it’s not my style to whine in the manner that earns people money, it wasn’t a financial venture. It was a way for me to try and put stuff behind me – a lot of anger and resentment – and yeah, to ‘move on’, for sure.

[Billy used a photo of the man responsible for the abuse documented in My Fault on the cover of Thee Headcoats’ 1992 record ‘Pedophile’] I’ve no idea if that guy is still alive. You know, I did try to track him down, I tried to make some enquiries at the time [of publication], and was told, "There’s no point." I was interested in having a word with him.

People are very keen on historical sex abuse now. There’s obviously some very nasty serial sex abusers out there, who were or are in the public domain, and maybe now it will catch up with them and bite them. Generally, I think the reason that there’s so much furore around paedophiles is that it’s usually a family affair but people want to make it to do with ‘the man outside’. Of course, when you’ve got people in high government involved with this kind of thing, they should be called to account. But generally if you’re going to be sexually abused, it’ll be someone you know; if you’re going to be raped, it’ll be someone you know; if you’re gonna get murdered… And I think – dare I say it – people have such a fear of who we actually are. How do you go about saying these things? How do you say that sexual abuse is far more prevalent, far more commonplace than we think? How do you say that it’s that ‘commonplace-ness’ which makes it far more likely that people will look for the bogeyman outside. Because otherwise society would have to look at itself, and of course that would not be tolerable.

In any case, as with My Fault, I’ve always used whatever is going through me – or what’s going on around me – as the subject matter of my art, my music, my poetry, which are all really one lump. But I do like to discern between things and call writing ‘writing’, poetry ‘poetry’, fiction ‘fiction’, painting ‘painting’, etc. Although I’m active in lots of artistic areas, I don’t feel it necessary to label it ‘art’, because I’m not trying to impress the powers that be in the art world. I don’t seek any validity from those people in order to feel that what I do is sacrosanct. This is why we, in terms of my bands, have never signed contracts or done what other people required of us.

I’m actually currently working on things that feature in small sections of My Fault; I’m writing a book about the month or two that I was a ward porter in a mental asylum after walking out of art school the first time. It’s a time described in My Fault, but I’m now exploring it in more depth. My job as ward porter was mostly cleaning toilets, but I got into a bit of trouble because I was telling the doctors how they should be treating the patients, giving advice [even though] I was a shit-shoveller really. I was only there for a short spell but I used to go back there and draw pretty regularly for two or three years after I worked there, before it was closed down.

You know in those days it was quite strange; it used to be the ‘Kent Asylum’. You could just drive in, park, walk through the main gate, walk up to the patients’ canteen, get a cup of tea, sit down with everyone and draw. And no one would ask you a thing. There was no security or anything. That’s how the world was, just a little while ago.

A fellow called Larry Clark got me to write a screenplay for My Fault (I also wrote one for Notebooks Of A Naked Youth) and I was meant to direct it, but I’ve been fending that off for about 13 years! The last thing I need to do is be a film director. That’s organising lots of people, which is a nightmare for someone like me. People can’t believe I’m not champing at the bit to do it. I’ve been in films a little bit, amateur films in the 1980s. Tracey [Emin] was in one or two of them, Eugene [Doyen] used to make them, and Trace was my girlfriend so she got to be in a couple, but honestly, just doing those was enough. The only reason I was in those films is that I was the only person Eugene could find who had the patience to wait around while he made a film. Anyone who’s seen them can corroborate that it wasn’t to do with any innate ability on my part. Eugene didn’t know any actors. He did all the photography for a lot of our LPs, and he was a pal of mine, so it was payback time.

5. Thee Headcoats – The Messerschmitt Pilot’s Severed Hand (1998)

That was just a bit of fun. We were meant to go into the studio to record an album, and that would usually take us a day. We used to record at Red Rodders’ studio in his parents’ garden, but that morning his wife had gone into labour so he couldn’t come and record. Bruce and Johnny had already arrived, so I just set the half-track up in the cellar room where we used to record a lot of the backing tracks for the [Thee Mighty] Caesars on a G36 half-track tape machine. We recorded it live with the guitar turned down so we could hear the vocals – and that’s why the guitars are so weak – you have to make a compromise. I like the fact that it was recorded in that way because of the fellow’s wife going into labour.

With [album track] ‘We Hate The Fucking NME’, I just thought we were stating what everyone felt! I thought were on the side of anyone who worked there as well – but it turns out some people are easily upset! There’s a fellow called Johnny Cigarettes who had kittens about it. He said we should become gravediggers for our own self-integrity. He really took it really badly. He tried to get into a show we did at the St John’s Tavern, and I told Slim Chance who was on the door – he’s like a no-nonsense dustbin man, he worked the bins during the day, a streetfighter – and Slim said, "There’s this guy on the door who says he’s from the NME, wants to come in on the guest list." I said, "He can come in – we’ve written a song for him!" So we played ‘We Hate The Fucking NME’ and he walked out. Some of the NME lot got it – turns out some of them put it on their answerphones! They’re smart, you know? I mean if you write for the NME, you must hate the NME surely?! Otherwise there’d be something wrong with you! The thing I like about it is the lyrics: "NME owned by IPC, me and Madonna hate the NME." Me and Madonna were on there, we joined forces. And then it mentions some of our friends, who were in groups – all the riot grrrls, they used to come and see us, and yeah, they were some of our biggest fans! So you know, I thought it was all just fun. I guess some people are just easily upset.

I gave up drinking when I was 32, which is an adolescent occupation anyway, but I’ve obviously still got adolescent elements of my personality which I can’t contain. I think I actually went more punk rock after I stopped drinking – I had to direct all this fury somewhere else, at the NME or whatever. My trouble is I get into a sort of ‘hero’ mode. I seem to think it’s my job to sort everything out, which it obviously isn’t.

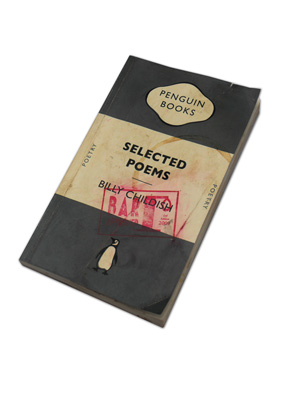

6. The Uncorrected Billy Chyldish: Selected Poems (2010)

I always liked Penguin Classics, and then the intro to DH Lawrence’s Selected Poetry really worked if you just swapped my name for his. So we thought that if we published my poems, but changed the picture and the introduction and the bio to refer to me instead of Lawrence, then that’d be nice, and I’d have a Penguin book, which wouldn’t happen otherwise. But Penguin got upset about it, and said that they wanted the books sent to them and destroyed. We said that we didn’t trust them to destroy them. It was quite funny because I was doing an interview for Libby Purves on Woman’s Hour – I’ve been on it a few times, Libby Purves she likes me, she’s quite nice and kind to me – and so she said, "What are you up to?" And I said, "We’ve been instructed by Penguin to burn some books." Which wasn’t quite true, it was stretching the truth a bit, but anyway. We weren’t allowed to use the Penguin logo or anything, so we did an official Penguin book-burning with their logo on, and did a poster for that, and then we did a limited edition publication where you would get a packet of the ashes: an official book-burning package. And Penguin did stop bothering us after that – they were on us for a while and then they gave up bullying us. They didn’t want to be affiliated with book burning, but also they realised we’d just be obtuse, we’d take it to another level, whatever they said.

We did another book; a really gorgeous hardback edition in the style of a 1950s Faber & Faber – with a foreword about me ‘by’ TS Eliot called ‘I Fucked Frida Kahlo’. It was done really beautifully, with a golden swastika on purple linen on the inside of it. And Faber didn’t even bother reacting. That book is really beautiful. It’s bound in purple linen with a golden swastika and the proper Faber & Faber dust jacket, and then the foreword by TS Eliot about me.

7. Solid Brass ‘Short Sunderland’ Door-Knocker

I live in the former house of Oswald Short of the Short Brothers, who built the Empire Flying Boat and various other flying boats. He was an all-round great guy. He was a great employer, a great free-thinker, an aeronautical engineer and pioneer of flight who treated his workforce outstandingly. For example, during the recession he turned his factories over to the building of bodies of buses to keep his people employed.

I live in the house that he lived in, which was over the factory. So I designed a door-knocker in an art deco style modelled on a Short Sunderland for the front door. I had it made and then cast. It’s a nice thing to do, to design door-knockers. It’s an area that not many modern artists go into. It’s the lesser trodden path. It’s part of my fetishisation again. Although maybe fetishising is the wrong term, because what it actually is is playing a game – a game with the energy of what the thing is. So actually ‘fetishising’ should be retracted. You work out what the game is meant to be, and you’re back at the doll’s house now. You understand what the dolls are supposed to do. And if you understand what the pieces are supposed to be doing then you understand the game you’re meant to play.

I’ve got a fascination with so many different things. It’s a constant for me (although not as much of a constant as hats). Also, you know, I’ve made a lot of wild pigs out of bronze, because I really like pigs. I’ve made some Aurochs, some prehistoric horses. Anything you go into you need to have your bullshit detector on. Anything is open to corruption, so you have to be able to discern the bullshit for yourself.

8. Dazzlelac Guitar

My friend Fabian, who runs Fab Guitars, made me my Buff Medways Cadillac guitar, and so I suggested doing some other editions. I’m a really big fan of Norman Wilkinson, the British Railway poster artist who developed ‘dazzle’ camouflage. Dazzle camouflage was invented to confuse range fighters on submarines: a rangefinder works by having a split image joined together. A range finder is the same as they used to have on cameras – when the two images come together you have the range. Dazzle camouflage used to confuse rangefinders, so that you could no longer tell if what you were seeing was actually where it was, or whether it was going at the speed or in the direction you thought it was.

Dazzle camouflage might even predate cubism, although it looks kinda cubist. It’s more like vorticism: it’s great, this British invention by this marine artist. The thing I love about it is when they were developing this camouflage they used to make a model of each boat and each one was custom-made separately. And Wilkinson got all his mates who were artists to go along to the dockyard, because nobody was allowed to oversee the painting of it unless they were an artist. So he wouldn’t allow the designs to just be drawn up and sent along to the dockyard to be completed, he had to have a proper bona fide artist there to make sure it was done properly.

Whether it was a glorious failure or not, I just love the way Wilkinson went about it. Apparently he had great confidence that it would work, and actually if you understand how a rangefinder works, it should succeed in confusing them. Imagine if you’ve got a periscope on a submarine, right? You know they used to paint fake bow-waves (the point at which water breaks over the bow) on some of the boats. So if you’re going to torpedo a ship you need to know its speed and direction, because obviously the torpedo has to meet the boat at the right time.

Being torpedoed in the mid-Atlantic must have been one of the most terrifying things going in the north Atlantic run during the second world war, and so the development of camouflage that could prevent this was a big deal. And it did make sense. I just like the idea that this guy came up with this stuff. So I thought, let’s have some dazzle camouflage guitars.

9. CTMF Hand-Painted Boats

We hand-painted 45 model boats with a copy of our 7" acting as the keel of each one, and sent them off to their doom (and our loss of money). CTMF stands for either Chatham Forts or Cunts, Tossers and Motherfuckers. It’s meant to be a Thames estuary invasion fleet, not conceptual art. Think about the poetry book, when we decided to burn it. We didn’t start it off with the idea of burning it – it was a secondary act. In the hands of a conceptual artist – say someone like Gavin Turk – they wouldn’t be able to do it with their own poetry in it, because they don’t HAVE the poetry, they don’t have the background. Now if they wanted to do a Thames invasion fleet, they can’t put a real 7" in it, because they didn’t have a punk rock group. With us it came from a natural playfulness, with a trail of thought behind it. It’s like with the first Pop Rivets album and how we did the sleeves ourselves – that was not conceptual art, that was about how to do something with style.

It was the same when we did the book and we did the invasion fleet; these were things that I would like to exist in the world. And they’re good fun. What I liked with the Thames invasion fleet is that the 7" became the keel of the boat.

Only a few of the vessels were found in the end, and one of them was by someone with a record player, who actually played it. I really like that. We really made the boats, we really made the records, we entered into it; it was a real story. We offered a reward if people found them, and for that reward we got three returns. One person found one but wouldn’t return it – they didn’t want the reward. You see we were trying to trick them because the reward was worth less than the boat – to us, anyway.

There are two video versions of the launch, one with the song from the 7", one with Sibelius (I’m a big fan, he’s a crazy boy) as the soundtrack. I had my daughter launching them with me.

I don’t have a problem with conceptual art apart from that it’s boring. And if the CTMF invasion fleet IS conceptual art, then it’s one of the rare occasions when conceptual art hasn’t been boring! I don’t have disdain for conceptual art, I just have disdain for it when it’s boring. I’m a big fan of Kurt Schwitters, have been since I was young. I guess I just have a dislike for marketed rebellion, things done cynically or boringly, without wit and vim and vigour. Some of the early dada stuff sounds like a right laugh to me but then some of the things that I saw, when Tracey used to take me along to see things by Damien [Hirst] or Sarah [Lucas], were just boring to me.

It was similar to the whole Stuckism thing. Co-founder Charles Thomson was a sworn enemy of mine, but he suggested doing it and came up with the title from one of my poems. I was still on talking terms with Tracey at the time. She didn’t really get totally angry with me until she got nominated for the Turner Prize. I didn’t change my views, it’s just that Tracey had changed hers, and she wanted me to endorse things that I wouldn’t, and she got a bit upset. I like manifestoes, and so we did The Stuckists and wrote some, and then the first exhibition came up and I saw what was in it, and I knew I needed to leave the group immediately. It was less than a year after it started. And then Charles said to me, "Well, can you pretend to still be in the Stuckists?" So I said, "Oh, yeah, sure, I don’t mind pretending to be in the group."

I get very annoyed because people go on about me "attending demonstrations" and I certainly never attended a demonstration in my life. That’s beneath me. I didn’t attend any Rock Against Racism or any Right To Work marches in the punk rock days. I went to the Damned anniversary at the Marquee in ’77, when they released ‘Stretcher Case’ as a free 7" to celebrate. There were these kids there who said to me and my mate Steve, "Are you going to go on the Right To Work march?" And I said, "Is there a Right Not To Work March?" We didn’t go, and in the end we were really pissed off because the Sex Pistols played it.

I’m an ideas man. The reality is something I can’t deal with. I’m an armchair Stuckist. I like drawing up plans. Everything for me is like ‘miniature world’. It’s hard to explain to people. It’s like when I talk about the doll’s house. If you had a doll’s house when you were a kid, the dolls would do what you wanted. And that’s what I like. If you’re an ideas man or a doll’s house man, it’s all about a miniature world. The railways run the way you want them to run. They crash when you want them to crash. And maybe this is why people like making records, or writing things, or painting.

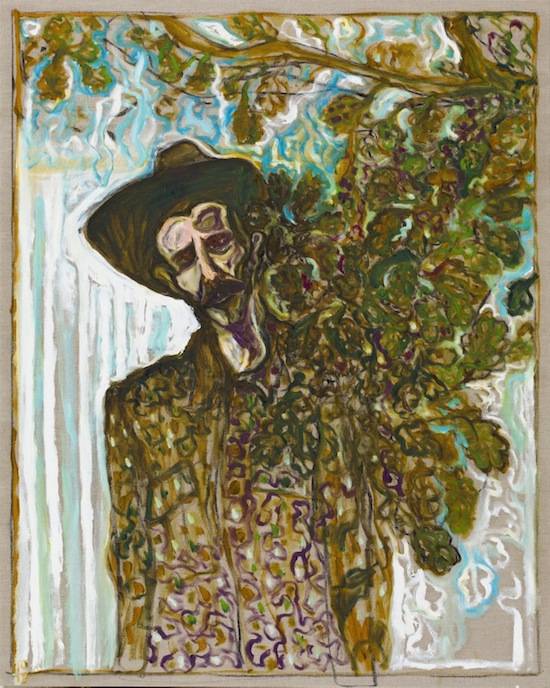

10. ‘Edge Of The Forest’ (2013)

Camouflage features in this painting too. I’m big on camouflage. I like the recognition that things aren’t really nailable, even though everyone wants to nail them. I like being camouflaged. I guess it’s similar to the way in which I’ve gone under so many different names, and worked in so many different areas and have so many different interests. And yet people are so definitely sure of what I am, without actually having the first idea of who I am or what I do or what I care about at all! I like animals who are camouflaged. I wrote a poem about it, actually. It was kind of about Picasso, because he tried to lay claim to the dazzle camouflage idea. He saw dazzle camouflage being used in 1914 and said, "We cubists thought of that." And I said, "This is how we know that Picasso is full of himself."

There’s more than one way of cooking a goose. Camouflage can be based in confusion rather than concealment. I really like things that confuse people from focussing on their target. I’ve always believed that the important thing is to be an ever-moving target. If you’re an ever-moving target, they can’t shoot you.

Acorn Man by Wild Billy Childish And CMTF is available from all reputable music outlets now