It was a muggy Manhattan afternoon when I spotted him: Ol’ Dirty Bastard, standing alone on a Broadway sidewalk, with one trouser leg rolled up and a Big Mac in his left hand.

My first day in New York had been spent plodding between the usual tourist attractions, gawping at the sharp-angled skyline, trying to keep pace with the city’s hustling intensity. Then, just as it felt like time to retreat from it all, the sight of a familiar face startled me.

Over the four years leading up to that moment, in June 1999, Dirty occupied a mythical status in my life. Amid a genre known for taking itself too seriously, Ol’ Dirty Bastard spent his career expressing things that other rappers wouldn’t dream of saying on record – whether it was living on welfare, catching gonorrhoea or living with his mother.

His music felt so unapologetically eccentric, so brazenly unself-conscious, that some of that exuberance rubbed off on you just by listening. The man seemed fearless: immune to criticism, impervious to judgement. As a teenager growing up in Ireland, floundering for an identity of my own, the weird world of Dirty felt like a perfect fit.

So when our paths happened to cross that afternoon, I didn’t stop to think the situation through. Instead some primitive impulse took over, compelling me to stride up to the man and exclaim: "Dirty… I fuckin’ love you!"

The words just blurted out, tumbling to an awkward halt. I could feel myself trembling, so unsure of what was happening that I said it again. Dirty paused for a beat, gazing at me intently, before replying: "Well, I love you too!"

All these years later, I still can’t imagine a better response. He indulged me graciously, laughing when I tried to persuade him to visit Ireland, filling me in on his plans for a new album. Dirty’s demeanour seems all the more remarkable now, looking back, considering the difficulties he was struggling with. He’d been in jail, shot at several times and was under surveillance by the FBI.

I didn’t realise any of that at the time. Streaming updates about artists and their antics had yet to become all-pervasive. Apart from the occasional sliver of information that slipped through, all I had to go on was the music.

As that began to change, Dirty’s life turned into headline material. Long before he passed away from an accidental overdose in 2004, two days short of his 36th birthday, his merits as an artist became increasingly overshadowed by his reputation for erratic behaviour.

I can’t pretend there was no sign of it that day. Maybe it was the way he drifted off on a tangent too difficult to follow. Maybe it was the curtain of bloodshot pink that hung halfway over his right eye, so thick that you couldn’t see through it. Maybe it was the way that, shortly after we shook hands and said goodbye, he marched into traffic – with cars honking and swerving all around him – and disappeared into the blare of rush-hour.

Even as a naive teenager, that encounter felt like a glimpse into a world of which I had no real understanding or experience. But as his legal troubles spiralled into a sideshow, I could tell that there was much more to Dirty than the buffoonish caricature he was often portrayed as.

There are enough stories about his brushes with controversy. You can find them almost anywhere his name is mentioned. But they add little, if anything, to the music. Somewhere along the line, the qualities that made him special and the esteem he’s held in by other artists have become overlooked.

George Clinton, for instance, believes that Ol’ Dirty Bastard introduced a new cadence to music. Kanye West said he’d cut a piece of his finger off just to have that voice. Questlove credited ‘Brooklyn Zoo’ as being so radical that it changed the way he thought about rap music; that it felt as if Screamin’ Jay Hawkins had somehow made the best single in hip hop history. Ali Shaheed Muhammad of A Tribe Called Quest said that if you listen to Dirty’s lyrics, there’s no question that the person behind them is a mastermind.

"People are always going to talk about his personality," says Wu-Tang’s Raekwon. "But, to me, he’s no less than a Jimi Hendrix or any other great artist who had a nutty way of thinkin’. More importantly, I think he left a legacy behind. Part of that is us, the Wu. Part of that his son, Young Dirty Bastard. And then there’s all the things he did that nobody had seen before."

In 1993, the Wu-Tang Clan altered the shape of hip hop with their seminal debut, Enter The 36 Chambers. Their idiosyncratic sound – gritty, dark, aggressive – was built around snippets of the kung-fu films and soul music they’d grown up with.

Yet even among a super-group of nine MCs with distinct styles and mysterious monikers, Dirty’s half-sung/half-rapped delivery stood out. He combined rock star charisma with an unorthodox sensibility, introducing himself with lines like: "I come with that ol’ loco style from my vocal/Couldn’t peep it with a pair of bifocals." Each appearance seemed to jolt first-time listeners into the same reaction: "Who the hell is that?"

"Dirty was popular right from the door," says fellow Wu member Cappadonna. "He came out with that original energy. His style, his aura, even his hair – nobody did it like him. We the mighty, mighty Wu-Tang but Dirty was the one who put the Wu in the Tang, man. He was like a shooting star leaving a trail of colourful dust behind for everyone to bear witness."

Despite appearing on just a third of the Wu’s debut, Dirty had a solo deal lined up before the album was released. A 1993 appearance on the Stretch Armstrong and Bobbito Show made such an impression on Dante Ross, an A&R at Elektra records, that he took a cab straight to the radio station. Ross immediately envisioned signing Dirty and Method Man as a duo in the style of Run DMC but Rza, the Wu’s producer and de facto leader, had a different plan.

The Wu had orchestrated a deal with Loud records that gave the group full creative control. That strategy freed up every Clan member to sign solo deals with other labels, allowing their individual profiles to benefit from the maximum resources possible. It also enabled the Wu and its circle of affiliated acts to infiltrate hip hop on an unprecedented scale.

Dirty’s contribution would be unmistakably his own. Return To The 36 Chambers: The Dirty Version may not be the most celebrated Wu-Tang release – Gza’s Liquid Swords and Raekwon’s Only Built 4 Cuban Linx…, also released in 1995, are both considered cinematic masterpieces – but Rza has since described it as the freest moment of expression within the group’s music. Twenty-five years after its release, the album still feels like an anomaly worth celebrating.

"The styles they were bringing [together] were studied and developed through a process of constant challenge," says Ethan Ryman, who worked as an engineer on Dirty’s solo album as well as the Wu’s debut. He remembers the entire Clan being present for the sessions, with heads battling each other incessantly and outsiders occasionally turning up to try their luck.

"With all their records, creatively, Rza seemed to have things mapped out with some precision. He brought everything he needed and when there was a gap that needed filling, he was good with coming up with something quickly. For me, there was a freedom in the idea that this record was not going to sound like other records of the time and the group was totally good with that. I think we all knew we were in some kind of uncharted territory. It was exciting."

The process took so long, however, that Method Man’s Tical ended up becoming the Wu’s first solo outing, released on Def Jam in 1994. Buddha Monk – ODB’s hype man, collaborator and close friend since childhood – explains that this was partly because Dirty could be a stickler for detail.

"Most people don’t realise that Dirty was a perfectionist," says Buddha, who mixed the album in addition to performing on it. "He understood himself as an artist and that gave him the kind of critical ear that’s extremely rare."

There were times, Buddha recalls, when he’d be working on the album late into the night and Dirty would call from a nearby hotel, asking for playbacks over the phone to see how it was all coming together.

"Sometimes he’d pick up on something that wasn’t supposed to be there and I wouldn’t know what he was talking about," says Buddha. "He’d say, ‘G, I want you to stay on this phone and mute every sound until we find it.’ And we would. It was so amazing to me that he could hear that shit, even on the phone, when I couldn’t hear it standing there in the room."

Dirty’s mercurial nature could be a nightmare to schedule around. Whenever someone wanted to find the rapper, whenever they needed him to show up somewhere, Buddha was usually the first point of contact. He likens their dynamic to Batman and Robin – so much so that when he was incarcerated for violating parole in 1993, he believes it had a knock-on effect on the album’s progress.

"Dirty waited for me," says Buddha, who recently published The Dirty Version, an ODB biography he co-authored with Mickey Hess for HarperCollins. "He took care of me while I was in jail and when I got out, there was a limo to pick me up. He took me clothes shopping, put money in my pocket and we went straight to a video shoot for ‘Da Mystery of Chessboxin’, ‘Wu-Tang Clan Ain’t Nuthin’ Ta Fuck Wit’ and ‘Method Man’ – all in one day."

Return To The 36 Chambers retains trademark elements of those Wu-Tang classics, but at a looser pace that leaves room for Dirty’s unhinged flow and filthy humour. Its supporting cast includes a formidable Wu line-up (Rza, Gza, Raekwon, Ghostface Killah, Method Man and Masta Killa) as well as Dirty’s own crew, the Brooklyn Zu (Merdoc, Buddha Monk, Raison the Zoo Keeper, 12 O’Clock and Shorty Shitstain).

The album opens with an ad-libbed monologue where Dirty, speaking as Russell Jones (his birth name), introduces proceedings as something "nobody in the history of rap ever set theyself to do." By any standard, this rambling passage would be considered cavalier to the point of absurdity. But it wasn’t all clowning around. By comparing himself to James Brown, then interpolating Blowfly’s ‘Taurus (The First Time Ever You Sucked My Dick)’ and sampling Richard Pryor’s ‘Have Your Ass Home by 11:00’ – all within the first five minutes – Dirty offered listeners a frame of reference for his outsized personality.

"Whenever we were in the studio, Dirty was always focused and knew what he was doing," says 4th Disciple, a producer whose credits appear throughout the Wu-Tang catalogue. He was present for much of the album’s creation and co-produced ‘Damage’ with Rza.

"He would give a lot of input as to how he wanted things to go. If you had a drum coming in a certain way, he might say: ‘Double up on it right there.’ Sometimes you just had to follow his lead. Meth is like that too. When you sit down with him, he’s like: ‘Put this right here, hit it like that.’ Dirty had the same work ethic. He had a lot to do with the sound of that album."

The production’s murky, inebriated quality provides the perfect atmosphere for Dirty to do his thing. Integral to this was Rza’s gift for isolating the briefest snippet of an old groove and extrapolating from it with hypnotic effect. You can hear it in his use of ‘I’ll Never Do You Wrong’ by Joe Tex on ‘Snakes’ or Otis Redding’s ‘Let Me Come On Home’ on ‘Brooklyn Zoo II (Tiger Crane)’.

For years, Dirty had been keeping track of the sounds Rza accumulated in his library, pegging certain beats – like the one in ‘Hippa To Da Hoppa’ – for himself. But he also had his own way of incorporating what could be called ‘sung samples’.

Dirty was a soul fanatic at heart, known for spontaneous renditions of favourites like Brainstorm’s ‘This Must Be Heaven’, Natalie Cole’s version of ‘Good Morning Heartache’ and ‘Everybody Needs Love’ by Gladys Knight & the Pips. Inevitably, he couldn’t help breaking into others’ songs midway through his own material.

The album is littered with vocal riffs on everything from Jim Croce’s ‘Leroy Brown’ to traditional folk ditty ‘Long Legged Sailor’. He warbles the opening line of ‘Blue Moon’ for no apparent reason at the beginning of ‘Brooklyn Zoo II (Tiger Crane)’, then mimics the guitar lick to Kool & the Gang’s ‘Hollywood Swinging’ on ‘Harlem World’. There are also nods to ‘Action’ by Orange Krush, ‘Raw’ by Big Daddy Kane as well as ‘Rapper’s Delight’ by the Sugarhill Gang among many others.

One day, during the initial stages of production at Rza’s basement studio in Staten Island, Dirty’s wife was reprimanding him elsewhere in the house. In a flash of inspiration, he invited her to repeat it on microphone while he belted out ‘Somewhere Over the Rainbow’. It’s presence in the middle of ‘Goin’ Down’ sums up the album’s scatterbrained charm.

"He had a unique mix of creativity and fearlessness that made everything he did kind of unpredictable," says Ethan Ryman, the engineer. When Dirty overheard a chintzy keyboard backing-track that Ryman was producing for another project, for example, he immediately wanted to get in the booth to sing over it. Ryman thought he was crazy, that there was no way he’d want to put something like that on the album. Instead it became ‘Drunk Game (Sweet Sugar Pie)’, a ridiculous moment of schmaltz which Ryman says was intended to parody the R&B ballads of the time.

"He didn’t want to change anything or track the music for real – he wanted it just like that," says Ryman. "Unfortunately the original version was lost and we re-recorded the vocals at Chung King [Studio] with none of the original spontaneity. He was happy with it. I wasn’t. That was a crazy track to put out on a major label! There was apparently a lot of trust going on with Elektra at the time, which I think was both excellent and rare in the old version of the music biz."

Lyrically, Dirty’s style was rooted in the old-school hip hop culture of 1980s New York – "the funky fresh music that was stereotyped," as he put it. Partly, this is because he’d built up a reserve of material which had been honed through rap battles, radio appearances and live performances going back many years. The ferocious verse on ‘Brooklyn Zoo’, for example, was something he dropped on the Stretch and Bobbito Show in 1991, while ‘Cuttin’ Headz’ was originally a Wu-Tang demo from 1992.

"A lot of the rhymes on that album was stuff I heard when Rza first introduced us back in ’90, before Wu-Tang," says producer 4th Disciple. "We used to stand out in front of my grandmother’s house, just listening to him freestyle and kick his rhymes under the moonlight for hours. I knew from the start that this was a unique individual who was going to do something special."

Not all of those rhymes were written by Dirty. ‘Damage’, ‘Don’t U Know’ and ‘Protect Ya Neck II The Zoo’ feature material that originated from his cousins Rza and Gza. All three grew up together in Brooklyn during the 1980s, performing as a group called Force of the Imperial Master, also known as the All In Together Now Crew. The lyric books the trio used to carry around, Raekwon says, were a formative influence on Wu-Tang. Sharing rhymes was just a natural part of that dynamic.

"I think when he was making that album, nobody was denying whatever he tried to do because we knew he’d complement the material," he says. "A lot of stuff Dirty did on his own but sometimes there were other things I guess he had his eye on, like, ‘Yo, you know what? I’m takin’ that.’" He laughs. "That’s how it is when you come up in the game with so many members in one group: ‘Hey, if you love the rhyme, you can have it. You’re my brother. It don’t mean nothin’.’"

Dirty’s other strategy was simply to spit whatever words came to mind and see how they fit together. Some of his vocabulary drew from the teachings of the Five-Percent Nation, which inspired him to adopt the name Ason Unique at an early age. Some of it comprised non-verbal fills: an ability to cough up bursts of percussive gibberish and indescribable sounds.

Those jarring improvisations are central to the album’s energy. The outline of ‘Brooklyn Zoo’ may have been percolating in Dirty’s head for years but its rabid delivery was unplanned. Midway through an altercation with his crew, Dirty stormed into the recording booth and knocked the song out in one take, blending in fragments of the argument that just took place. Seeing that impulsive approach first-hand helped Buddha Monk to develop his own production style.

He learned that you didn’t always have to stay on the beat, that it didn’t matter how many words you fit into your rap, that you could abruptly stray into a different song or just pause to take a deep breath. Then there was the technique of leaving microphones running while people loosened up in the studio, gifting you extra material to pepper the songs with whenever necessary.

"I would never have thought about any of that without Dirty," says Buddha. "At times, I would be like, ‘What the fuck is wrong with this dude? He didn’t just say or do that, did he? We’re definitely not getting shit like that on the radio.’ But in reality, when the A&Rs and everybody else heard it, he could get away with things that other people couldn’t. It was like they expected that stuff from him because of this character, the Ol’ Dirty Bastard, that everybody loved."

There aren’t many artists who would consider recycling lines in different songs on the same album. Yet somehow Dirty could make it work. He had a way of switching up his tone and phrasing so that it sounded like several voices jostling for space from one moment to another. It didn’t matter if he repeated himself, if the lyrics made little sense or if he sung off-key.

Return To The 36 Chambers is the kind of album where having a full verse played backwards doesn’t feel out of place. ‘Brooklyn Zoo II’ even pauses to provide a brief recap, jumping through previous songs like a record stylus slipping across the turntable.

That there’s little attempt to contain Dirty’s swagger within traditional song structures only strengthens the album. Singles ‘Brooklyn Zoo’ and ‘Shimmy Shimmy Ya’ are essentially comprised of one verse and a looping refrain. Most other tracks eliminate the need for hooks altogether.

It makes for an organised mess that manages to be sordid but soulful, gelling together in spite of its eclecticism. Each song seems to capture Dirty in a different state of composure, whether it’s manic, perverse, disorientated or just downright silly. The one constant is his unwavering bravado.

"Listening to that album is like one whole day of hangin’ with Dirty," says Raekwon, laughing. "I think what made it so different was the fact that he wasn’t afraid to challenge himself and do what he wanted to do. Plus, the production fitted his style perfectly. A lot of people credit Rza for building the Wu but at the end of the day, in my eyes, you can’t credit Rza without crediting Ol’ Dirty Bastard because he gave Rza the spirit to be who Rza is. You can never front on that."

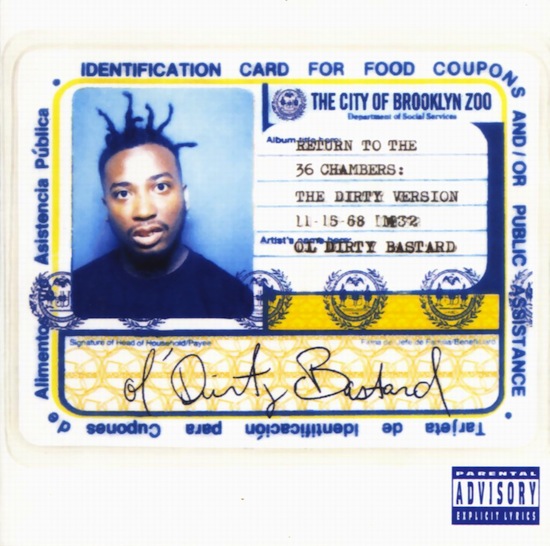

Before the album’s completion, Dirty visited the Elektra offices to broach an idea. He reached into his pocket and pulled out his ID card for food coupons and public assistance. "Yo, could we make this my album cover?" he asked Dante Ross. The art department was happy to oblige, swapping the New York Welfare Department stamp with the Wu-Tang logo while replacing the rapper’s name and address with the album title.

Dirty’s outlook was the antithesis of bling. He spoke plainly about where he came from, the life he lived and the lack of reward that rapping offered. "Who the fuck wants to be an MC?" he barked on ‘Rawhide’, "if you can’t get paid to be a fuckin’ MC? I came out my mamma’s pussy, I’m on welfare. Twenty-six years old, still on welfare!"

The rapper took pride in being the same person both on and off the microphone, refusing to leave the neighbourhood he grew up in even when it put his safety at risk. The cover art was a way of letting fans know he was as real as he claimed to be. But he also thought it would be amusing to see if an image of poverty could become the face of a hit album.

Return To The 36 Chambers reached number seven in the US charts and sold over 500,000 copies within three months. The album also proved a success among critics, who hailed Dirty’s bizarre lyrical content and original vocal style, leading to a Grammy nomination for Best Rap Album.

Its release came at a critical juncture in hip hop. Wu-Tang’s rise demonstrated that underground artists could engineer success on their own terms, with Return To The 36 Chambers in particular proving that there was an appetite for the unconventional.

"ODB crosses boundaries beyond just hip hop," says Chris Manak, founder of Stones Throw Records. "He carried himself as someone who has a lot of fun and people want a piece of that."

Manak, better known as Peanut Butter Wolf, started Stones Throw a year after Return To The 36 Chambers, building it into a platform for off-kilter, innovative hip hop artists such as Madlib, Dam-Funk and J Dilla as well as other acts too leftfield for traditional music channels. Seeing Dirty strike a breakthrough without compromising himself, Manak acknowledges, felt encouraging.

"He was rowdy like the Beastie Boys when they first came on the scene yet he wasn’t afraid to make R&B records like ‘Ghetto Superstar’ with [Pras and] Mya or ‘Fantasy’ with Mariah Carey. When someone gets a taste of success like that, they usually change their own sound to get more of it, but he kept his music raw and weird."

Though Dirty would complete just one more officially released album, 1999’s Nigga Please, his influence has endured. People see it in the amorphous vocals of Nicki Minaj, the wild-eyed abrasiveness of Danny Brown and the dirt-bag humour of Action Bronson, who described Return To The 36 Chambers as "one of the illest things in life." By breaking rules, taking risks and letting loose, the album set a new standard for MCs to express themselves.

"What made it such a breath of fresh air was Dirty’s willingness to boldly go where a lot of people are afraid to go," says Cappadonna. "Even I hold back a bit, you know? But Dirty would break all the barriers of what’s allowed and what’s not. That record was saying: ‘Just be yourself. Go ahead and be ‘hood, if that’s who you are, without being ignorant about it. You don’t have to be accepted by anybody but yourself.’"

That’s exactly how it felt when I first discovered the album 25 years ago. I just didn’t realise how many others connected with his music the same way. At the time, sourcing new hip hop releases in Ireland could be tricky. Only two other people in my entire school put as much effort into that process as I did, which forced us to trade tapes and swap CDs as if they were exotic contraband.

Without any real gauge to measure Dirty’s popularity, he initially struck me as something of an outlier, even an underdog. It was only later that the reality caught up with me.

I remember listening to the radio in bed when a newsreader announced his death. I remember being amazed that I could cue up ‘Brooklyn Zoo’ in a Brighton karaoke club. I remember dancing to ‘Shimmy Shimmy Ya’ in the small hours of a wedding. I remember, not long ago, seeing a graffitied Wu-Tang logo at a train station just outside the town where I grew up. Beside it, sprawled in light blue spray-paint, were the words: Ol’ Dirty Bastard. Something tells me the person responsible is another teenager who views ODB in a legendary light.

When I share my story of meeting Dirty with his mother, Cherry Jones, she lets out a heart-warming laugh. "That’s my son!" she says. "He always had time to speak with whoever was speaking to him. He never shied away or said no and he didn’t care about no celebrity status."

People loved him for his sense of humour, she says. His flair was just something that came naturally. As a child, ‘Rusty’ was the one who’d jump right into a puddle rather than walk around it. Growing up in a household with a reputation for musical talent, he developed the kind of presence that, even at the age of 11, drew interest from record labels. Although Dirty’s mother says she never saw him excited about anything in his entire life – not even being nominated for a Grammy – his work was something he took seriously.

"That’s why it makes me feel proud that he still matters after [being gone for] 10 years," she says. "I was just at the store across the street and when I told the girl there who I was, she said she just had to give me a hug. That felt so good. I’m glad he’s still remembered because, when you think about it, many people aren’t. It means a lot when people pay tribute to his talent. He was good at what he did."