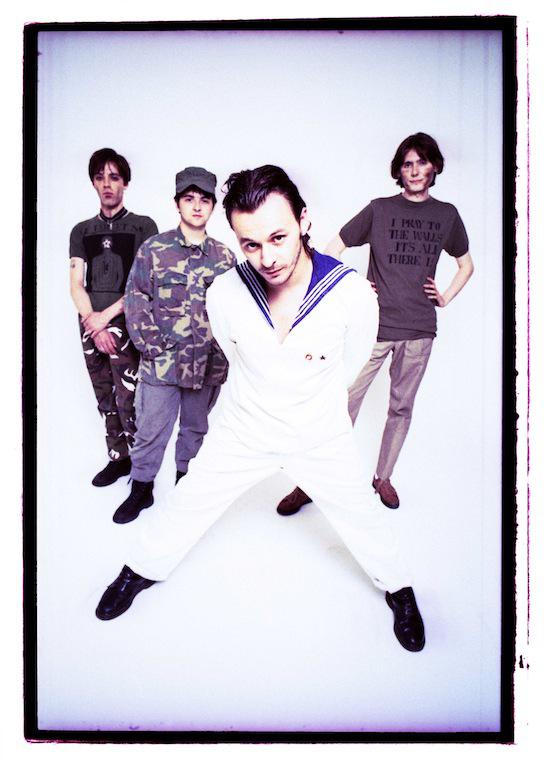

Next month, the Manic Street Preachers start their 20th anniversary tour for The Holy Bible, an album that had a great effect on me, a young music journalist, and on so many others – a record of burning rage, cold fury and self-directed violence that took the basics of a rock band but also felt like the careening post-Bomb Squad hip-hop that they loved. The Manics have performed irregularly in the US over the years, but this will be the first time they’ve toured that album here. In 1995, all that happened was a short promo tour for the American release (in its US mix, since made available via 2004’s deluxe reissue). James Dean Bradfield and Richey Edwards were to do the trip together, but Edwards checked out from the Embassy Hotel early in the morning of the American flight, on 1 February 1995, and went missing. Bradfield assumed he’d be in touch soon after and carried out some initial interviews before it became clear that Richey had disappeared. Bradfield returned to the UK, and both the US release of the album and any further plans for a US tour were called off.

I was one of the journalists he spoke to before he flew back. I was living, then as now, in Orange County, south of Los Angeles. Thanks to a friend who worked in Sony’s college radio department, I had a chance to talk by phone with Bradfield. I’d only received a promo tape half an hour before the call and hadn’t had chance to listen to the whole album.

I believe I pieced together something from the interview for a fairly new LA-area alternative rock magazine which as far as I know barely lasted a couple more issues. To my knowledge the interview has never resurfaced in any collection of articles online or elsewhere about the band. I myself don’t have a copy of the first article, though I half-remember reading it in print. The interview published here has been written up for The Quietus from the original tape of the interview; I hope he doesn’t mind this long-forgotten moment from his past re-emerging now.

I was just got the album about half an hour ago, and I’m halfway through – I got up to ‘4st 7lb’. I was trying to distinguish the difference between this album and previous ones. It’s almost exuberant, and it’s almost unfriendly.

James Dean Bradfield: I think we’ve just gone back to our old indie days, or at least the first couple of singles we released, ‘Motown Junk’ and ‘You Love Us’, on Heavenly. The first version of ‘You Love Us’ was much more punk-based. Right at the start we got compared to The Clash quite a lot. And I think we’ve gone back, we’ve focussed on why we started the band, on all the bands that we loved – Joy Division, The Clash, the Pistols, Gang Of Four, stuff like that. It’s almost like we went away and recorded this album outside of the record industry. We went and recorded it without telling the record company, in a demo studio. We did it really quick. It’s more direct. I don’t think it makes concessions to the listener at all. It’s really honest, and it just goes for it.

So it’s more of a return to what you started with, rather than a change from it?

JDB: We looked at the last album and… bits of it I like, but I do regret certain things about it. I think we lost sight of what we originally were.

The last album did seem… too polished, maybe?

JDB: There wasn’t enough aggression on it, basically. I think I ignored my old record collection. I went back home before I did this album. I went through my old records, and it was Wire, Pistols, Clash, and I was thinking, This is why I was into music, and these are the bands that I wanted to sound like when I was young. Fucking get back into why you were into music in the first place.

And so you just recorded this album without telling the record company?

JDB: We went and did it in a demo studio, without a producer. We just recorded the songs. As far as we’re concerned it’s not produced, it’s just performed and engineered. It’s just down, you know?

So one day they were asking, "What are you going to do next?" And you were like, "Well, as it happens, we have this album here."

JDB: No, but it was almost like that. It was like, "We’ve got this album, it’s nearly finished. Do you want to come and hear it?" And of course we needed to mix it. But once the record company knew we’d gone and taken control of the situation, and they heard what we were doing, and they heard the directness, the energy and the attitude, they just went for it. They thought, Ah well, that’s okay. We took charge of their own destiny and I think they were almost thankful for that. It takes a lot of work off their hands.

Are you still writing the music with Sean Moore?

JDB: Yeah.

Have you written any lyrics for this album? I know you haven’t for previous ones.

JDB: I’m still the voyeur. I write the music and sing other people’s lyrics.

I take it you’re just very comfortable with the lyrics that Nicky and Richey come up with.

JDB: Well, you know, my dictum, my rule, is that I never, ever write the music without the lyrics. I get the lyrics, then I sit down and I write the music. Other bands, they’ll get lyrics and they’ll go, "I’ve got a song that fits that." They’ll have a couple of tunes hanging around, which they’ve just written sitting around the house, and they’ll just put it to the lyrics when the lyrics come to them. I don’t do that. I get the lyrics and I sit down and I interpret it. I only ever write around the lyrics. That’s one of my rules. The other rule is that before I start writing a tune for a song, I’ve got to take the lyrics for the song to a level of my understanding. There’s no point in sitting down if you don’t know what the lyrics infer; there’s no point trying to write to it. I take what I do on a very interpretive basis.

Does that always agree with what Nicky and Richey are thinking about when they write the lyrics?

JDB: Yeah, I’ve got another rule. I have all these rules, which I have to understand they’re not necessarily going to accept. This may sound a bit pretentious, but it’s very voyeuristic – it’s almost like an acting role. Somebody who acts doesn’t necessarily have to agree with it, he’s just got to try to understand but he doesn’t have to accept it. But we’ve all grown up with each other, in the same environment, with similar socioeconomic things, and there’s hardly anything we disagree about. So many things we’ve been through are shared that I feel a natural affinity with the lyrics anyway, just by default because we all grew up with each other.

https://open.spotify.com/album/7FiPNXyrCGGWFqO4btxPEe

Do you have any desire to write lyrics of your own?

JDB: I like the way we do things. I think I see a very complete picture of what we do. I think there should be more interpretation in pop music. I like doing it, I’m completely satisfied.

Most of what I’ve learned about you, apart from through listening to the albums, is from the British press – mainly from Simon Price at Melody Maker. I’m interested in how, especially when you first signed to Sony, you had this dichotomy between your independent message and this major-label, corporate structure. There was a sense of, “No matter what happens, we’re part of the machine." Isn’t it almost too easy to say that?

JDB: I’ve always thought that we validated our existence by having so much commentary in our songs, you know? I think our lyrics are brilliant and I think what we say in our lyrics is brilliant. I’m full-on very pompous about that, and I don’t even fucking write the things. To get wrapped up in arguments about setting up this new independent state for groups and stuff would completely obliterate any chance we’ve got of just putting our point across. It’s just a very, very simple argument. If you’re worried about bands, worried about them getting caught in a corporate machine and prostituting themselves, then you might as well just wipe off your Billboard Top 40, because all those bands are doing it through major distribution. They’re doing it through the corporates. They are at the mercy of the corporates. The one thing we’re all doing is, we’re actually keeping independent language. We’re keeping our own dialogue, and that’s all you can do. I think it takes a fucking genius to get in the Top 10 and not have some kind of corporation help. It’s a fact of life. My father’s got a job and he’s a good man; he believes a lot of things I believe. I really admire him. But I know his limitations, and I know our limitations. If you think you can take an independent label and make it big worldwide without the help of a corporation, then you’re a genius. We’re coming to terms with it. There’s a lot of things we care about, and there’s a lot of things you’re right about. We devote ourselves to our songs, basically. That’s one issue I’m not going to put myself on a rack about, because I know we’ve thought about it, we’ve been on an indie, and the mere existence of independent labels… they’re cool, you know. They gave us a break. But one thing you realise when you move from an independent label to a corporation label is that independent labels can be corrupt too – there’s corruption on a smaller scale. There’s good and there’s bad things about independents and corporates. If you really care about what you say in your songs, you’ll come to terms with it and just try and get your point across.

Is there a danger that the lyrics can get completely lost in the music, that people won’t pick them up? Do you feel that you can only get across to so many people?

JDB: We’ve been brash sometimes, but even we wouldn’t be so contentious or arrogant as to demand something of the audience. I go on the stage, put it out there, and it’s at the mercy of them. If somebody comes up to me and says, "I love you as a band. I love the music," and I ask them about the lyrics and they say, "Well, you know, they’re fine, but it doesn’t really have an effect on my life," I’m not going to pummel their skulls and say, "Why aren’t you part of this intelligent experience?" I’m not that didactic. I’m not that dogmatic. Not by nature, anyway. We do it for ourselves first. There’s no prerequisites for what somebody’s going to take from you.

One thing I also found out through Melody Maker was about Richey and his hospitalisation this past year. At one point, in an interview with Taylor Parkes, you and Nicky were complaining about all this highly unwelcome attention, lots of misinterpretations. It was almost like some of the British press thought, Oh, America had Kurt Cobain and now we have this – our own little homegrown tragedy. Was there a sense of that?

JDB: I won’t go into details, but when it first happened, we didn’t think, Oh my god, we’ve just finished an album. The promotional push is all fucked up. We didn’t think that. We thought, Oh, fucking hell, you know, our friend, one of our best friends, had gone completely off the fucking edge. And we just dealt with it as four friends, first of all. We realised we had to catch the unwanted attention from the spooks in the press, who get slightly morbid about it, so we wanted to keep it under wraps. We wanted to keep it a secret, we didn’t want to make a big thing out of it. And they found out about it – I’m sure somebody from the hospital there in Wales wanted to inform the press about it – so we had it on our hands and they were just breaking the story. You know the British press. We didn’t want to seem like we were going to try and use it to our advantage, but some people were going to think that. So basically, yeah. I thought there was a lot of morbid interest there. A lot of myth-makers started getting their presses out. Everybody wants a myth. Myths are so rare these days; myths are a thing of the past. And they just want to be in on it. It’s the nature of the British press. We manipulated it – it’s the nature of the beast – so we can’t really complain, but I did feel they were slightly irresponsible, especially towards Richey’s family. They didn’t consider the far-reaching effects for his family, and I don’t think they were giving his family any privacy. That was terrible. The British music press sets itself up on a higher moral ground, and I thought they were being very hypocritical at one point.

Beyond the music, how calculated is your image and your projection of yourselves, on stage and on video?

JDB: It isn’t calculated. When a band pretends to bond with an audience, when a band pretends to be so earnest on stage, and gets offstage and treats everybody like shit, that’s very calculated. We just have a very simple explanation of what we do. What we do on stage is basically us copying what we saw as kids, which a lot of people do. We were into The Clash, we were into Public Enemy. We try to project an image which is perhaps slightly larger than life, especially in Nicky’s case or Richey’s case – it’s normal for us because those are the groups we were into. You are what you admire, or you try to be. I see some groups go on stage and touch hands with the audience, and they think they’re giving the audience something, and that’s bullshit. I’ve got too much respect for the audience for that. I may not smile much but I like to have a good time. I do. It’s a licence to make a complete arsehole of yourself, and I like that.

From what I’ve heard so far, every song on this album seems to be introduced by a little sample. I was amused by the one at the start of ‘Ifwhiteamericatoldthetruthforonedayit’sworldwouldfallapart’ – was that something that you found, or did you create it? Because it sounds like a lot of the ads I hear on TV here.

JDB: It’s something we found, yeah.

Oh god, I’m sorry. It’s another example of American culture at its worst.

JDB: It’s the best country in the world too, though. That’s what our song’s about. The first time I came to America, it was the most immediate impression I ever had: "My god, it’s the best country in the world. My god, it’s the worst country in the world. My god, it’s so interesting – it’s the most ethnically diverse country in the world, and one of the most racist in the world." I loved it and I hated it at the same time. It was such a strange, contradictory experience coming here. I think I’m beginning to love it more than I hate it, to be honest.

You talked recently – in another recent issue of Melody Maker – about how Guns N’ Roses were good at one point and now they’ve collapsed. Why do you think that happens? How do you try to avoid it?

JDB: People loved Guns N’ Roses because they were like cartoon characters, like caricatures, and I don’t think they realised that. Axl Rose is like a composite myth rock & roll character and as soon as he starts taking himself seriously, you know it’s going to go seriously wrong. Also, they don’t realise that that’s how an audience bonds with a band. You see a band like Guns N’ Roses and, as corny as it is, they did seem like a gang. Then they all started splitting up, it’s obvious they’re not even friends anymore. What’s the point? That kind of naive bond you have when you’re a young kid, it’s all lost. It’s the same with The Clash. Once all the in-fighting started, you just know that the bond that gave them their music is just gone.

I’m not asking you to predict the future, but do you think that if that happened in your band – and I’m not saying it will – would you split up?

JDB: The only that would make me feel like splitting up is if we didn’t get on anymore, because that would be a disaster. We’ve all been best friends since we were born. If we felt like we weren’t best friends anymore, I’d be beside myself. That’s never going to happen, I don’t think, but that’s what would make me feel like, This is not worth it. It’s something I enjoy with my friends, being near them, and if it ceased to be like that then I’d call it a day.

I forget which one of you said this, in an interview I read somewhere, you were talking about how you felt you’d read everything, listened to everything, you were almost like, "Well, now what do we do?" How would you answer that?

JDB: I think it was Richey who said that, but I think he was talking about being a fan – he wasn’t talking about Richey the artiste or anything. He was talking about being a consumer, somebody wanting to find things he could like and be a fan of, and I think what me and Richey were talking about there – and he articulated it a bit clearer to me, and I kind of understand – we just realised at one point that we’re in love with failure. Everything we love just completely failed, whether it be an ideology, even religion… all religions have failed. Well, our religion has failed, Christianity, if you’re brought up in quite a Christian background. But all our favourite philosophy or ideology, it’s all glorious failure. Our idea of us was packed with much more excitement than reality. It was much more idealistic than the reality. We failed on our own terms, too. I think that’s all he meant, really. When you’re young, you believe in so many of these things, and you think you can make them work. You think you can take an old idea from an author or something and make it work. But then you realise it’s this whole composite of failure – modern life is failure. I think that’s what he meant. There’s nothing you can really, really, really believe in. There’s nothing you know that can’t be tarnished by failure. It didn’t stop me trying to find something. But you do get the realisation that you can’t expect anything to really succeed on its own terms.

If you’ve reached the point where it seems everything has failed, and yet you’re still keeping your eyes open and seeing what might happen, then what do you do – not as a musician but just as a person? You gave me some sense of that, but is there anything more you can say?

JDB: No, to be honest. I really have just come to terms with it. It’s like, you just shop around for little bits. You become a magpie and you steal a lot of bits and you take what you need. Almost like we’re a lot of thieves, really. We just realise that there’s no point taking the whole deal so we just take a little bit and use what we need.

What do you think you’ve been able to do, with your three albums – or if that has failed, then how has it failed?

JDB: I think, at the start, we established a language. I’ve always thought the band had an exclusive language, in our lyrics, the way we presented them with the music. I always thought there was something really illogical about us – you could never apply any kind of logic to us. I always thought it was quite religious, that we spoke in tongues. And we did lose it there for a while on the second album but I was quite invigorated by that in a way, because we recognised this ourselves and we got ourselves back on track. We proved to ourselves that we could go and record an album outside of the record industry. We had the strength to do that. We established our own dialogue again, and didn’t worry about the consequences. So it’s good – we started out with so much arrogance and we started out so blase about what we thought was our own intelligence. We realised that we made a mistake there, but we addressed the situation ourselves. Nobody had to do it for us. For me, that’s the biggest achievement on this album.

What do you think is the function of art, of your art? Is it to portray something? Is it to force a decision on the viewer, to leave options open?

JDB: The only way I can answer that is by talking in reference to where I came from. I have a very working-class background on that stuff. When we were just getting into music, the miners’ strike was going on and I realised one thing. That strike lasted a whole year, and it completely failed. Everybody lost out on that deal. They lost their jobs, they lost the fight, they lost everything. But I realised in the community, people were almost in love with this martyr kind of thing. They’d all become martyrs. They’d all fought to the end. At least they had that, even though they were left with nothing and they lost, they were almost partying on it. They had a big party, like, "Yeah, we showed our spirit." I understand that, but I think it’s one of the sicknesses of the working classes, that they still want their martyrs. Almost like I said before, they’re still in love with failure. That’s perhaps why we seem a bit nihilistic or a bit unemotional in some of our songs. I think that’s because of where we come from; it’s quite a sickness, really, to be in love with being a failure, to want to be a martyr to your own community. That’s the only thing we’ve managed to do for ourselves, to take ourselves to a different plane. Even though I love where I come from, and I love all the people where I come from, I think that’s our biggest achievement: we realised we don’t want to be in love with failure all our lives, and we want to do something about it.

Read more about Manic Street Preachers’ North American Holy Bible tour here