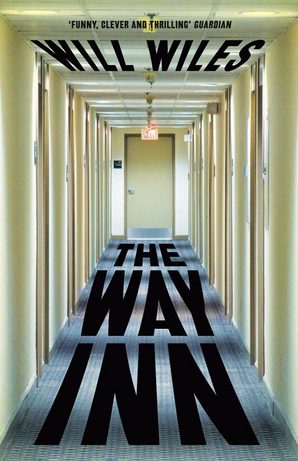

Will Wiles’ The Way Inn is a novel about professional conference-goer Neil Double – a man whose line of work is attending conferences on behalf of other people. Neil always stays at The Way Inn chain of hotels; he takes pleasure in his anonymised, atomised lifestyle, having turned his professional life into a toxic personal philosophy. However, after meeting the mysterious Dee in the hotel one day, Double slowly discovers the darker, brutal heart of the hotel chain, and tries to find the truth behind its sinister mechanisms.

Lee Rourke: The hotel, Will argues, the experience of being in a hotel, is entirely individual and personal. Nobody else exists but you. The hotel is always designed for somebody else. He talks about this relentlessly in the first third of the book (it’s broken up into three sections): about the construct of what a hotel is and how it functions, for the individual and within society, but also architecturally. Will writes quite frequently on architecture, he used to be the deputy editor of Icon magazine, so he knows his stuff. What he is posing in The Way Inn is a death of architecture, symbolised through ‘non-spaces’.

There are two spaces within this novel. There’s the ‘non-space’: tied in with the supermodernity of Mark Augé and people like that. Then there’s the ‘junkspace’ – proposed by Rem Koolhaas, in his famous essay from 2001 – the idea being that junkspace is a style of architecture of the non-space. What Will argues is that this junkspace is the materialisation of the death of architecture. All architecture is becoming homogenised: identifiable by its glassy, smooth exterior. Which is funny, as it’s not about the exteriors anymore, it’s about the interiors; the personal interaction within the architectural space. Koolhaas argues that these new architectures of the non-space are in fact the same building, and they are infinite, and every architect is working on the same building, over and over again. This echoes, directly, what happens in the novel.

Kit Caless: I went to see an exhibition at the Royal Academy last year called Sensing Spaces (curated by Kate Godwin). It was all about the architecture of the interior. Using the Royal Academy rooms, architects and artists were allowed to experiment and try to find new ways of existing inside a space. There was one room, designed by Pezo von Ellrichshausen and Mauricio Pezo, in which, upon entering, you are confronted by four imposing classical columns. Only as you get close, you realise you can enter into the columns. Then the space becomes circular and you can climb up inside the columns and view the room from the top. The whole point was that architecture is no longer about the outside, but this exhibit argued that it was unchallenged and homogenised on the inside too, and they were trying to counteract that.

Godwin seemed to be arguing that we no longer strive to make new interiors either, let alone exteriors. My approach to this, in the super modern world, is that a good deal of our lived interiors are now online. Space, the physical space of the interior, no longer matters as much. You live your personal life digitally.

LR: You live your personal interior in a re-imagined space of what already is. All our spaces, those which surround us, are basically blueprints that we already know, and they function in this way psychologically. For example, in a lift, where time is supposedly suspended, the space within, behind the closed, sliding doors is invariably mirrored. As Will points out in his novel, the lift is a non-space where time seems to stand still, and you don’t want that to happen. You don’t want the occupier of the space to spiral into a loss of self, so the mirror reflects the self, and gives a mirror to the self endlessly in the non-space.

KC: It allows you a distraction from the echoes of nothingness, of boredom or fear, or crisis?

LR: Exactly. Will speaks – through his narrator – of the corridors and non-spaces of the hotel. He writes of how in these worldwide, chain hotels, by each lift door, there might be a little sofa that nobody sits on. It gives the impression of comfort, of soft surroundings within a hardened, geometrical architecture, which is basically what hotels are. Hotels are boxes stuffed with data, stuffed with ourselves. They require these soft edges in order for us to function properly, or for us to feel that it’s real, that we aren’t too far from home. There’s corporate art that lines the walls, there’s a beautifully manicured olive tree in a beautiful pot, there’s soft furniture.

This ties back to a book called The Poetics of Space by Gaston Bachelard. He argues that our interior spaces, i.e. our architectures, are intrinsically linked to our imaginations. He uses the analogy of the home as the centre of our imagination. It’s similar to what Borges says – the house is the same size as the world – or rather, it is the world. For Bachelard, like Borges, the spaces we create around us are in fact our universe. It’s why we soften the edges of our interiors. Bachelard uses the analogy of the bird’s nest: outside the nest there’s all these thorns, twigs; hard edges that are sharp and cause injury, but inside it’s beautifully smooth. That’s what we’re doing when we open decor catalogues and interior design magazines: we are softening the edges of our interior architecture.

KC: After reading The Way Inn, I went to a wedding in Frankfurt and we stayed at a midrange hotel, like the one in the book. It absolutely changed the way I saw how the interior of a hotel functions. What I found interesting was how the borders and boundaries of each functioning section of the hotel almost blurred into each other. There were chairs to sit around in reception, soft and inviting, a TV on the wall opposite the lifts with a screen of a fish bowl, and then underneath, some posh ergonomic chairs no one sat on because they were near the toilets and looked more like art installations. Then a good number of steps into the space was the reception desk. As I looked beyond the desk it morphed into a bar, which lead down to a restaurant area at the back. Even the hoteliers, the assistants on reception doubled up as barmen in the evening! I was confused where the delineation of space was. In the same way that you go to a conference or a department store and the boundaries of each brand, or section are fuzzy. Move through it and the Ralph Lauren brand clothes are almost touching the rival Hugo Boss clothes, but there’s no wall, or physical barrier; you can walk between them. In the same way that in Westfield Stratford food court you can buy Thai food from the Thai kitchen but sit on the tables outside the Italian restaurant because the seating is fluid, there seem to be no obvious borders. You have a large rectangular open space but you can’t break up the open space, but somehow you still have to create a demarcation of space.

LR: It’s all mapped. It’s a form of circuitry. The homogenised neoliberal architecture of conferences and the arteries that are connected to the conference – the restaurants, the hotel – they all have to interconnect, in order to keep a form of circuitry going, a form of momentum that allows a) the business to be done and b) the products to be consumed. That’s basically what is happening in this novel.

Will likes to throw in lots of glitches, though. Like the sky walkway from the hotel to the conference centre still being built. It’s unfinished. It doesn’t connect. There’s a short in the circuit. He presents a barrier to that sort of interconnectivity. He uses this as a warning for global neoliberal consumerism – it is easily broken. It highlights the fake smoothness of it. How it has to be modern, yet comforting and familiar, but not too personalised. This is the key to supermodernity, junk spaces and non-space, it all keeps us moving, keeps us consuming … as long as there isn’t a glitch.

KC: It also reflects the smoothness of the flow of money. Particularly if you think of global transactions and productions of wealth. Money gets washed very quickly in our current economic system. It moves around rapidly and gets tidied up, cleaned, and rehoused. The way Will writes about how the bed in a hotel is always remade, everyday, even if you are staying in the room for more than a night. There is no trace of the last person who used the bed, even if it was yourself! Each day is a new day that brings a completely fresh start. There are no pubes on the bed, there are no stains in the sink or toilet bowl. I read that to be a metaphor for the way money works in these systems.

LR: That’s a great point. The book is basically about the lie that neoliberalism gives us. It’s not clean and comforting. Consumerism is dirty, like money, that’s why they have to keep cleaning the beds. Money, literally in its physical form, is dirty. If you pick up any random note, it’s filthy. The business of making money – chrematology – is dirty, both metaphorically and literally. Shakespeare taught us this, as did Joyce. So all the way down, from the matter of money, to the re-imagined space that money creates, it’s dirt, dirt, dirt. This world is tied in with the spending and making of money, it’s a dirty business.

I think it’s brilliant that Will emphasises the idea that each day the beds are made clean, pristine, echoing the idea that we can re-evaluate, rethink and re-spend, cleanly each day. But really we’re not. It’s wonderful that one of the cogs in the hotel’s machine, Dee – who sees the patterns of the corporate art for what they are, and what they hide – says, ‘I don’t like making beds’. She realises all this. She sees into the dark heart of this homogenised living, of this cleanliness. And it’s at that point that the novel shifts gear toward this speculative, almost science-fiction-like last third, the clean edges of literary fiction are purposely sullied.

KC: Throughout the book there is a real sense of a power behind everything, of control. Without giving away the plot too much, there’s an obsession, in the heart of the hotel, with control. There’s a sense of the guests internalising the power the hotel has over them; of willingly submitting to the hotel’s wishes; you want the hotel to wake you up, you want the menu to be chosen for you…

LR: You buy into the lifestyle of the hotel as its guest. As the novel progresses, suits become very prominent, and when you succumb to the dark fall in the novel, or if you chose to follow that path, you are empowered by the suit that you wear. I don’t want to say any spoilers either, but when you buy into the lifestyle of hotel living, you buy into neoliberalism. If you look at adverts now, even when we are savvy to them, we are still influenced by them. From a basic cookery advert to a Levi’s jeans advert, they sell a lifestyle that is believable enough that you think you can buy into it. Whereas all you’re really buying is the product.

KC: Did you see that advert a luxury development company made that went viral recently? Where, essentially, Patrick Bateman tries to sell you his lifestyle, and thus his apartment, in this swanky new development in Tower Hamlets. The advert is first person narrative – a chiseled white guy who works in the city, who shows his life on the way to acquiring this flat. There’s late hours at the office, a break up with his girlfriend, nights out with the lads, a promotion, corporate accolades and the eventually, at the end, he suggests, ‘it’s all worth it’ because he has a flat with this view of the city that ‘could have swallowed him whole’. It’s promoting this idea of sacrificing everything just to own a view.

LR: And it’s a view governed by architecture. So it won’t be any old building, or built space, it’ll be a certain type of architecture that ties in with this consumerist project. It’s funny isn’t it: the real process of the individuations of the self are now tied in, not with spirituality, but with consumerism, which seems to be a modern form of spiritual gain. In order for the self to renew, you have to buy into a new idea of the self, which is an architectural and moneyed construction that you think exists, but it doesn’t exist. Like the hotel chain, the conference chain and the world around it, it is believably real, but unreal.

KC: The gap between work and pleasure has completely contracted. To the point where, in that luxury flat video, the man’s flat looked like an office, and now offices look like a flat – kitchens, lounge sofas, TVs, games etc.

LR: The new clocking in card is in the palm of our hands; it’s mobile technology. That’s the reason why lifestyle and work have merged. The reason why Google offices look like a cool apartment is because you do most of your work in the palm of your hand or a laptop, which is mobile, which you can do anywhere – so why set the aesthetic, the interior architecture differently? The shared box, once we step inside, becomes a re-imagining of our own desired homes. A lifestyle can be created around the concept of the home. These new spaces in the city are 24-hour businesses, consumerism, a 24-hour digitised mirror of ourselves, or what we’d like ourselves to be.

KC: And that’s why hotels enable work so well – as the hotel individualises you and serves all your comforts, what else are you going to do apart from work?

LR: You’re taken away from real creature comfort, to another form, which is designed to keep you logged into the network. That’s why Will makes the point in this book that you don’t really need these conferences, they don’t need to happen, but the reason they do happen is because they are necessary to keep us consuming, to keep us logged into the network. We need to feel like we are participating in the network, when essentially, we already are. You don’t need the conferences, you could do all this from home, or you could meet in a coffee shop and do business there. But the whole infrastructure and space to do business, is to make you feel like you are ‘doing business’.

KC: I think the architecture in the novel, and not just the buildings, but the development around the buildings is fascinating. The Way Inn hotel in the beginning of the book is a kind of out of town hotel, like a hotel version of Lakeside. You drive to it, all that exists is the hotel and the conference centre, nothing else is there. The hotel exists for the conference and the conference exists for the hotel.

LR: You see these spaces, particularly in America, which was at the forefront of the rise of supermodernity and consumerism. In order to consume you have to create the space to consume. The high street doesn’t work in the same way as these big open spaces do. Because the high street limits the ease in which you can spend. It’s too small, there are too many people. You can easily walk past a shop. But these new spaces, brought in by consumerist wealth, have evolved for us not to miss. In the USA the car takes you to consume; it takes you to the cinema where you see the lifestyles you aspire to, and next to these cinemas are the shopping centers where you can buy whatever it is that you were inspired by, that you saw on the big screen. Culturally it varies across the globe, but what you always need is the mechanism, the circuitry, the conveyor belt to bring you out of the self, out of the high street, out of the familiar and into the kind of space where the familiar is re-imagined and made easier for you to spend money

Kit Caless: I found that each different character in the novel – from the narrator, Neil Double, to the journalist, Maurice, to Dee – as we mentioned before, all approach the hotel in different ways. They all have a different relationship with the building and its mechanisms.

Lee Rourke: They are all nodes within a process of information sharing. Will Wiles calls the hotel a ‘grey labyrinth’. But he also describes it as a kind of ‘hall within a hall’, a box of data that both hides and reveals. He likens it to a shipping container. He sees the hotel as a hub of human data, from transactions to business meetings, to one-night stands and porn channels – there’s a buffering of information. Neil Double is intuitively tuned into the patterns that are created in this space, and experiences a joy of being amongst it that he doesn’t quite understand.

KC: I feel with Neil – like with what we were saying about being aware of advertising, but choosing not to see beneath it – experiences what Žižek calls ‘fetishist disavowal’: that we know something, but we chose not to know it. Neil Double knows how the hotel works, but he chooses not to know how it works at the same time.

LR: There’s a vanity to him, too. He loves being incognito but he also tells everybody his real name. His incognito email address becomes his real email address because all of the good stuff gets sent to the incognito address. His real email address becomes obsolete, voided. ‘Voided’ is actually a word that is used a lot in the novel: when Neil gets blocked from going to the conference centre, he is ‘voided’, and there are processes that the hotel claims they can’t ‘devoid’ or ‘unvoid’.

Neil understands, in that Nietzschean way, that he is staring into the abyss and the abyss is consuming him as he is staring into it. Neil is a voyeur who allows us to enjoy, at first, the consumerism and all forms of the spectacle, all forms of boredom. For us, Neil reflects our fascination with consumption. Then there’s Maurice, who seems to always turn up at the right time, who widens the leakages of the darker, inner sanctum of the hotel. And then there’s Hibbert who is this omniscient, all seeing brain who orchestrates the functions the hotel, who is the hotel.

KC: He’s very much the O’Brien figure isn’t he?

LR: Precisely. They work on a three-fold level, representing different approaches to consumption and the spectacle. And of course there’s Dee, who is the spanner in the works, pointing out that the reason why everything interconnects, is because you are stepping into a very dark world. It has to interconnect in the way it does, in order to keep us moving through it, because if we stop we will see it for what it is.

Lee Rourke: That’s the analogy within The Way Inn: this interconnected world of corridors and rooms and a continuous hotel that goes on and on. It has to go on or we see it for what it is. It ties in with the hyperreal, supermodernity, all these things that make us the way we are. And if we do stop, if the acceleration of modernity does stop – which it can’t – then you will see it for what it is. People like Heidegger were saying this in 1929. Heidegger uses the phrase, ‘standing in reserve’. We are used by technology, by modernity. He uses the idea of the power station and the damn: the free flowing water is us, the damn allows us to be used by the power station, then be churned back out again.

Kit Caless: It’s interesting now though, that catastrophe and a crisis of confidence in capitalism and our economic models is no longer a problem for those models. It’s ‘disaster capitalism’ at its most powerful. The idea that this economic model needs to bust, must bust, in order to grow.

I feel like in this novel, with the breaking of the hotel and the break down of the hotel, it isn’t a problem for the hotel, because it is infinite. If, say, we had a sequel to the book – the hotel would have come back bigger and better and stronger, principally because it broke down in the first place.

LR: The new forms of catastrophe are, as you say, not real. Things still go on. The banking system carries on as it has done, it’s just that we’ve seen some of the dodgy dealings that go on in order for the business to do what it does. The spectacle doesn’t stop, what stops is us. The catastrophe allows us to stop and stare longer than we normally do; we get to observe the spectacle for a while. But not for long. Things change. Maybe a CEO gets sacked or an MP voted out, and we come out of the economic slump and we stop looking, so we start consuming again.

KC: In the way that Neil Double steps out, away from the spectacle, or more like ‘inside’ the spectacle, and sees the inner workings of the hotel. But he can’t seem to change it.

LR: He knows the way in, but he doesn’t know the way out. The only thing that can show him the way out is the very thing itself.

KC: It relates back to what we were saying about the details at the beginning of the book. The first third is so heavy on the intricate set up of the hotel, of the little, well-thought touches – a picture of a cucumber on the menu to express freshness, the references to sleep and comfort everywhere. To me, this is designed to distract us while we are reading. These are methods of distraction that stop the reader from seeing the bigger picture at work. It provides the spectacle that hides the ugly truth. It’s similar to when I fly: I don’t mind flying, but if I spend more than a minute thinking about it, thinking how I’m miles above the ground in a metal box going at a ludicrous speed, I have to put a movie on, or read a book, or eat!

LR: You know the second most expensive thing (behind the engines) for airlines while building a plane is the in-flight entertainment system? The entertainment system is integral to the non-space, because it eliminates time, and waiting, in the Heideggerian sense. He says that when you are waiting for a train, the worst thing you can do is look at the clock, because that is when you observe the very thing that underpins everything – the passing of time and the slip into nothingness. To alleviate the terror of waiting in aircraft flight, they provide all these things that comfort us. The distractions; being served wine like in a pub back home, or reclining your seat like a bed and turning out the lights. These things take your imaginative space away from what is actually happening.

I’ve just read Tom McCarthy’s Satin Island, and the books are very similar, in different ways – if that makes sense. They are both about a buffer zone of information. So much information heads our way on a daily basis, it loses its meaning. But when you stop to look at it, there’s a pattern to all this information. Both books are about navigating and finding meaning in the patterns. In The Way Inn, Dee sees the patterns of the art work on the walls, and she imagines this conveyor belt of the same art work chopped up into different sizes, she sees that it’s just one art work, the same piece, throughout the 500 hotels in The Way Inn chain.

Both of the protagonists in these novels stop and observe the patterns of consumerism, of us consuming, and make sense of things through these patterns. They see an un-pattern, a hidden pattern that we don’t see when we’re caught up in the spectacle of it. As Debord pointed out, we’re so blinded by the spectacle that we don’t see what goes on behind it. Only there are these fractures in things that allow us glimpses, sneaky peeks into the things that lurk underneath.

KC: You’ll see all sorts of new ways the spectacle manifests too. In The Way Inn you have these video screens showing the sorts of people who come to the hotel, having fun or relaxing in the hotel, which you watch while you are actually inside the hotel performing those very acts you are watching. Much like in high street clothes shops, there are video screens of models posing and presenting a lifestyle, wearing clothes that you are about to buy, or you can buy in that space, in that moment. It’s the hyperreal Baudrillard banged on about.

LR: Yes exactly. Baudrillard is right when he says that the simulacrum, when you step into it, becomes real. He uses the analogy of Disney World – it’s fake, but once you step into it, past the barriers, it is real. That’s basically what modernity is, an unreality that is real.

Jonathan Lethem sees Manhattan as an unreality that is real. It’s based on the mythology of itself. Brooklyn and Dalston too, forget about the wide ranging cultures that live there or have lived there for generations, what really matters is the new form of ‘creativity’ that is happening in these places. That is what sells. You know, poor immigrants are not a lifestyle to sell, but the white-collar middle class professional creative is. And that’s why these places become hubs, they generate their own mythology and people flock to it.

KC: David Graeber wrote this article for Strike! Magazine called ‘Bullshit Jobs’. It explores how modern capitalism produces jobs of no worth, but pays a lot of money for that production. Let’s take marketing as an example – or some forms of ‘content marketing’, something I’ve done a bit of before. You are asked to create ‘content’ that isn’t directly selling a product, or isn’t directly about the brand itself, or what it produces. You write an opinion piece, or a how-to-guide, that is designed to draw people’s attention to the company, or the brand, but not necessarily sell the reader something. It functions only to ‘raise awareness’ of the brand, in the way that people raise awareness of a charitable cause or tough political situation. It’s unquantifiable, essentially. There are no direct sales from these pieces, only ‘visitor numbers’ to that particular page and how much ‘engagement’ there was with the site and some of the other ‘content’ on it. You have to write it because other people are writing similar things, or using similar methods. It’s banal and insidious, an almost hyperreal form of work.

I think ‘content’ is such an interesting word because the word itself is so bland and non-descriptive. Content is a perfect word to describe what ‘content’ is. So Graeber is saying that the people who have jobs that are actually beneficial to other human beings, nurses, teachers, rubbish collectors, you know, they are less well paid, highly stressed and often go unheard. Where as the marketers and the brand management gurus and the content strategists, are lauded and get huge awards for their work. The advert has become the product itself, in a way.

LR: This is why books like The Way Inn are important. They lift the veil of distraction for a minute and let us see beyond the circus into its darkened heart.

The Way Inn is out now in paperback, published by 4th Estate

Kit Caless is editor at independent publishing house, Influx Press.

Lee Rourke is the author of two novels, The Canal and Vulgar Things a poetry collection, Varroa Destructor and a short story collection, Everyday.