This is Andy Gill, the music critic rather than the Gang of Four guitarist, writing in the NME on 23 April 1977: "It is completely utterly unlike any other album you’re likely to come across. Ever."

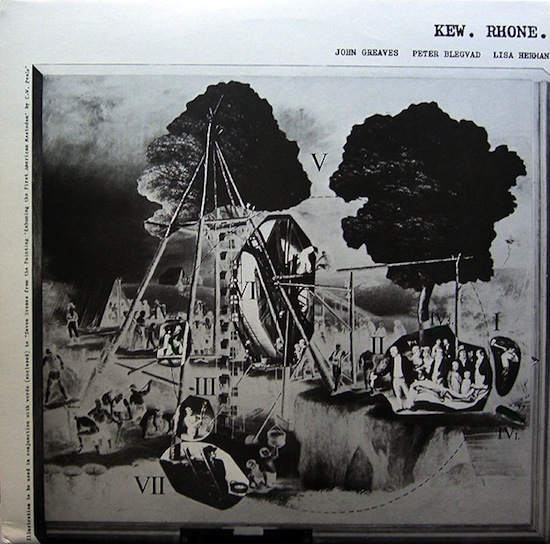

He’s talking about Kew. Rhone. And he’s right. The album didn’t exactly establish a year zero; it didn’t try to. But in terms of wiping clean the musical slate, it knocks spots off Never Mind The Bollocks. And yet Kew. Rhone. is not punk at all. It’s closer to an avant-garde musical. "The music is intricate, unpredictable, like show music from a parallel world," says Peter Blegvad, the man responsible for the lyrics and the cover art. Yes, cover art: integral to the album in a way that is only half-possible to grasp. But more on that later.

First, the words: densely allusive, playful, puzzling. "The lyrics concern unlikely subjects and unlikelier objects," explains Blegvad. "They refer to diagrams or function as footnotes, or are based on anagrams and palindromes." American poet Andrew Joron calls Kew. Rhone. one of the few rock albums that is genuinely surrealist in spirit and composition. Robert Wyatt liked it so much, upon its release, that he bought two copies.

Most albums don’t feature a track called ‘Gegenstand’, nor a list of deconstructed proverbs, nor a line like: "I am your quarry, you’re mine", which – to me, at least – becomes more appealing with every listening. Kew. Rhone. even contains what is surely the longest grammatically correct palindrome in popular music: "Peel’s foe, not a set animal, laminates a tone of sleep." Blegvad shrugs off the fact that some of the lyrical complexity will be lost on many listeners. Are there lyrical games no-one has spotted? "Probably. I’ve missed some of them too, I’m sure."

While Blegvad contributed these lyrical labyrinths, the music is by John Greaves, formerly bassist with Marxist art rockers Henry Cow. Enormously sophisticated and endlessly surprising, it was influenced by both Kurt Weill and Soft Machine – hence the sense of show music from a parallel world. One track, Pipeline, is described by Greaves as "a phenomenological bossa nova in 7/4".

Tasked with performing this stuff were vocalist Lisa Herman and a trio of avant-garde jazz luminaries: Carla Bley, Mike Mantler and Andrew Cyrille. If such names seem a long way from lyrical palindromes, well, that was the point. "John and I felt stressing the gap between the words and the music would be interesting," states Blegvad. "We made it as incongruous a marriage as possible."

That might sound willfully obscure; frustrating, even. But somehow it works. Because I wrote a book about Robert Wyatt, some people assume I like prog. But I don’t, particularly. Even some releases by groups of the so-called Canterbury scene, a sub-section or offshoot of prog and/or jazz-rock, don’t do much for me. But I’d happily stand up for the record Greaves and Blegvad created almost forty years ago in rural Woodstock. Part of the reason is that Blegvad and Greaves failed: the music and lyrics pull against one another, yet the whole thing is so deeply coherent; even catchy. As novelist Jonathan Coe asks, "How in the name of God could anyone take lyrics so oblique, so obscure, so cerebral and fashion such a memorable tune out of them?"

Certainly, Kew. Rhone. is extraordinary – right from those two dots, from today’s perspective reminiscent of a URL but in 1977 intended to represent the distance between the music and the words or, perhaps, a more general lack of certainties. "If conventional punctuation is used to disambiguate," says Blegvad, "punctuation like this might be intended to boost ambiguity, to raise questions, encourage guesswork".

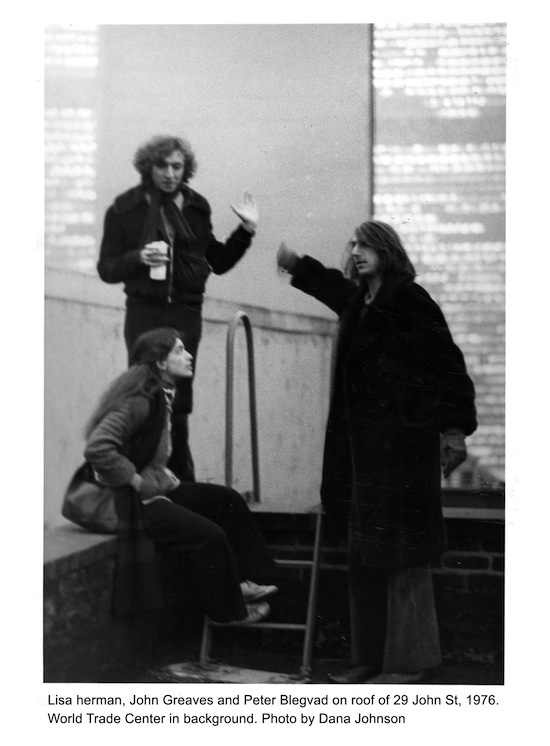

Blegvad and Greaves had met in Henry Cow, where they had sparked off one another to write ‘Bad Alchemy’ on the 1975 album Desperate Straights. Yet Blegvad – formerly one-third of the brilliant but underrated Slapp Happy – was kicked out, apparently for being "too flippant", before the pair had a chance to fully realise this collaborative potential. (Blegvad probably was too flippant, if by that we understand that he takes silliness seriously: he’s also a graphic artist, best known for his long-running Leviathan strip in the Independent on Sunday, and the president of the London Institute of ‘Pataphysics. Anyone even slightly familiar with that proto-surrealist pseudoscience, invented just over a century ago by Frenchman Alfred Jarry, will know that flippancy is not a charge that will sting.) Anyway, Blegvad and Greaves reconvened in the Catskills, at Grog Kill studios, to record Kew. Rhone. Grog Kill was owned by Carla Bley and Mike Mantler; it is indicative of the circles in which these two musicians moved that Charles Mingus dropped by one day while they were recording.

Is Kew. Rhone. an album to be "solved"? "It invites interpretation even as it resists it," replies Blegvad. "When considering the meanings of Kew. Rhone. we can only guess, we can’t know – which will put some people off. People who want definitive answers are unlikely to get whatever there is to be got from the Kew. Rhone. experience. Personally, I feel more at home with doubt than I do with certainty. What Keats called Negative Capability."

As Blegvad suggests, the album is, in some senses, unexplainable – yet, at the same time, it cries out for explanation. Hence the new book: 192 pages long and published by Colin Sackett’s Uniformbooks.

"As I wrote in 1985," says Blegvad, “’certain works by certain artists are not really complete until they have been thoroughly glossed, until commentary and exegesis, like colonies of clinging limpets, have extended the original contours and made the work of one the work of many. Kew. Rhone. is such a work. It cries out for annotation and analysis.’ No one else was gonna do it, so I did. Though it took me 30 years – and Colin Sackett’s encouragement and creative support."

"I wrote and illustrated the first half, an exegetical memoir, a track-by-track excavation," he continues. "The second half is an anthology of responses to the record by an international consortium – artists, writers, critics, musicians – who very kindly contributed texts and images to what turned out to be a very handsome volume."

As he suggests, Blegvad begins by discussing each track on the album, often diving off into footnotes. In the second half, we hear from a number of fans, including Robert Wyatt and Jonathan Coe, and such contributors as Lisa Herman, Andrew Cyrille and Carla Bley. Bley mentions a vow of secrecy during the recording as to the exact meaning or whereabouts of Kew. Rhone. (an anagram of Knowhere?). Such ambiguity is key to the record, and is happily retained in the book – which, says Blegvad, was precisely the intention: "to illuminate without dispelling the mystery of a work designed to resist interpretation even as it invites it. I think we pulled it off."

I mentioned at the start of this piece that Blegvad, as well as writing lyrics, was also responsible for the equally extraordinary imagery. The cover features a Victorian image with Roman numerals on top: like the lyrics, the image feels like a code, and one I for one have yet to fully solve. "The words were then locked in triangular tension with both audial and visual data," he says. "The songs were now, in a sense, 3D constructs. I was aiming to create a mental object with the presence and resistance of a physical thing."

This "triangular tension" between words, music and artwork hints at the fact that Blegvad as particularly well positioned to turn the album into a book. Born in New York but for some time resident in London, his career has included everything from drawing backgrounds for the Peanuts cartoon to creating ‘eartoons’ for Radio 3, from working as a lecturer to recording and performing with everyone from Faust to Andy Partridge.

Yet Kew. Rhone. – the album and now the book – somehow sums up his whole professional life (well, that and the Leviathan strip – now published in book form and the only parental guidebook you’ll ever need). The story I’ve always heard is that the album was released by Virgin on the same day that the label released Never Mind The Bollocks. In fact, the shift from progressive to punk was not quite that symbolic: Jonathan Coe says in the book that Kew. Rhone. in fact came out a good six months earlier. Still, the point remains that Kew. Rhone., with its 3D songs and 7/4 bossa novas, was progressive – but not the sort of progressive that makes you want to punch it on the nose for its smug pomposity. This was a version of prog that poked fun at itself, and at anything else, while being absolutely serious at the same time.

There are times I’d rather listen to Never Mind The Bollocks (well… Buzzcocks, maybe) than Kew. Rhone. and punk acts didn’t only sound good: Buzzcocks and their contemporaries also struck an important blow for artist entrepreneurship as a route to creative autonomy. But in musical and lyrical terms, it is Kew. Rhone. that looked forward. (Blegvad and Greaves even experimented with drilling a second hole, slightly off centre, to distort the music; although eventually abandoned, the scheme gives a sense of the scale of ambition.) It is a sign of just how far ahead of its time it was that Kew. Rhone. was re-released in 1998 as a CD-ROM. I’m not sure how many would have predicted, in the late 90s, that the CD-ROM would be the format that today looks archaic. Thankfully, however, we’ve still got paper, and publishers like Uniformbooks. Outside Bloomsbury’s often brilliant 33 1/3 series, I haven’t enjoyed a book about an individual album this much for quite some time.

More on the book Kew. Rhone. here. Different Every Time: the Authorised Biography of Robert Wyatt by Marcus O’Dair is out now from Serpent’s Tail