Like the man said: "Listen."

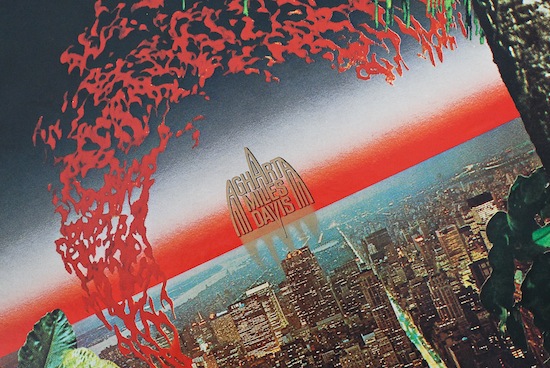

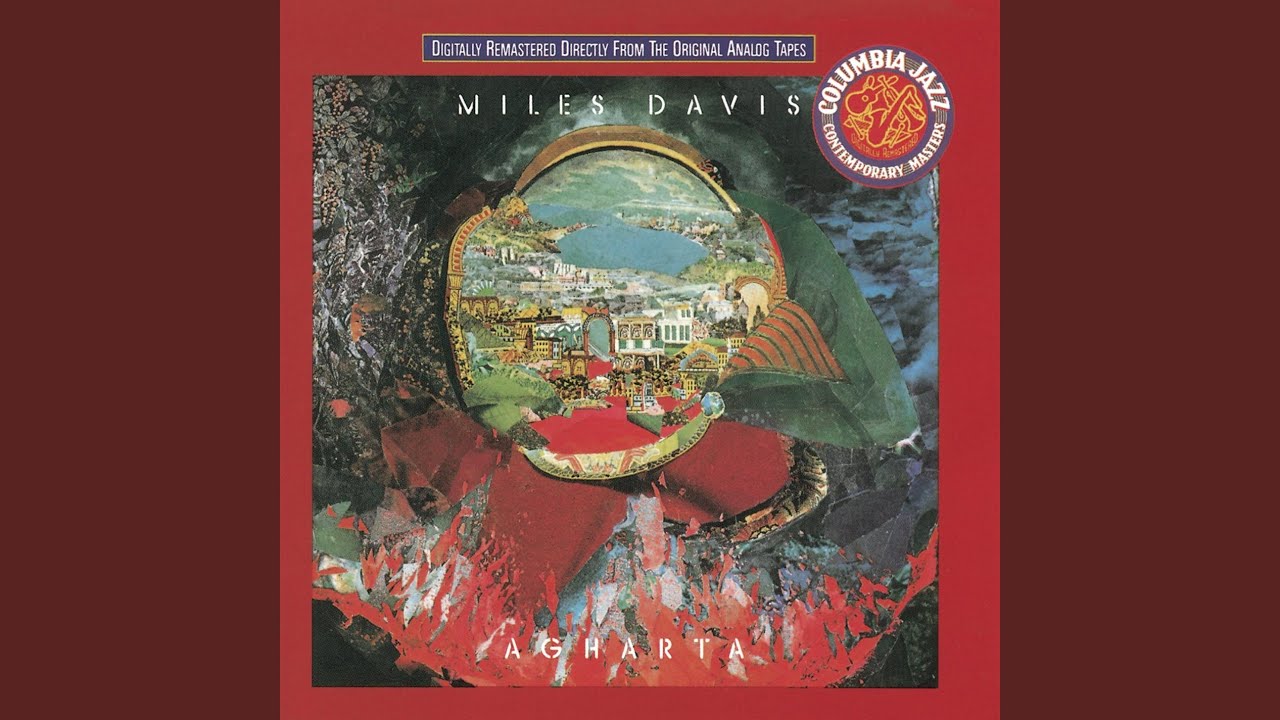

Almost exactly 45 years ago, on the first day of February 1975, an ailing Miles Davis and his road-hardened, shit-hot band rocked up at the Festival Hall in Osaka, and played two all-out, no-holds-barred concerts in one day. Both were recorded by Columbia’s Japanese office, then as now known as Sony. The afternoon gig was released later in 1975 as the double-LP Agharta, with the evening set seeing the light of day a year later under the name Pangaea. By the end of 1975 Davis’s health had deteriorated so badly he reckoned later that he didn’t even touch his trumpet again for five years. Extreme music, made by a man at the end of his rope, leading a band who were ready to run through walls to make something new and exciting every night. It should have been simple to hear, digest and enjoy, but a lot of stuff got in the way.

For starters, the way this music was made available, and the sequence in which those outside the Festival Hall that day got to hear it, was somewhat less than optimal. Agharta was released in the US in 1976, but Pangaea wasn’t made available outside Japan until the 1990s. Some of the same material, played by a similar line-up, appears on another live album, Dark Magus, which was recorded at Carnegie Hall in New York almost a year before Agharta and Pangaea but released, again initially only in Japan, in 1977. Dark Magus was less the work of a settled outfit fully into their stride than it was an evident staging-post as Davis sought the perfect formula for creating the unprecedented music he was in the middle of making. (A new, third, guitarist was added to the band for the first time that day, but left before the Japanese tour of 1975, while a second saxophonist was tried out, and promptly rejected after the show.) So this precursor record became the final part of a Japan-only trilogy of Davis live double albums a full two years after the iconic trumpeter had disappeared from public view – a three-year-old recording of the Agharta and Pangaea band in its embryonic stage presented as if it were a subsequent, perhaps even a new, release.

As if this wasn’t confusing enough, at this stage of his career Davis – never one to settle for re-doing what he’d already tried – seemed to have succeeded in alienating almost everybody. He pissed off the jazz purists at the end of the 1960s when he brought British electric guitarist John McLaughlin into the studio to help make the album In A Silent Way. Clearly a continuation of the moods, themes and pared-down approach adopted for the widely adored A Kind Of Blue (you’d have thought the Silent Way sleeve – Davis looking up as if for guidance, reassurance, inspiration, against a background of deep blue – would have been a bit of a giveaway), the record proved bewilderingly divisive, as polarising in its own way as that moment in Manchester when a concertgoer called Davis’s labelmate "Judas", and for much the same reason. (The temerity of each artist to incorporate an electric guitar into their work was the primary cause of teeth-gnashing, though the editing of the sessions, by long-time Davis producer Teo Macero, who turned different recordings into suites inspired by classical music’s structures, annoyed those who felt that fidelity to the concept of the unadulterated performance was of paramount importance.) If that wasn’t bad enough, the follow-up, Bitches Brew, took Davis further down the same road. Egged on by Columbia head Clive Davis, Miles started doing gigs with rock bands and appearing at festivals – it probably didn’t hurt that his jazz club dates around this time were getting crowds that sometimes didn’t hit three figures. The next studio record – A Tribute To Jack Johnson – is the best of the lot: what fans and detractors of the preceding records had claimed they could hear finally showed up on tape, with Davis and his band fusing rock, jazz and funk into a seamless, satisfying and richly rewarding whole. But the record sold poorly. While jazz aficionados were deriding him for "selling out", Miles’s new music was in fact so pioneering and different that it was going over everyone’s heads.

He’d taken this music as far as it could surely go, so Davis did what he always tried to do next, which was to take it one step further. On The Corner, released in 1972, was vilified at the time, and has had the balance reset far too heavily since in reappraisals that hail it as a masterpiece. The record has easily as much wrong as right with it, and in many ways it represents the sound of almost two decades of careful and craftsmanlike refinement of ideas, sounds and style being driven at a steady pace and with care and deliberation into a solidly built brick wall. After the final sessions for the album were finished, in early June 1972, studio recordings seemed to take a back seat to live work for Davis. The band was still recording, but to no clear or obvious purpose. The sessions appear not to have been convened with the express intention of making a new album, and although bits of them turned up on a couple of widely ignored singles and on the mish-mash double LPs Big Fun and Get Up With It (which collated material made over a four-year period but came out on the cusp of 1974 and ’75, as if it was a new studio album), much of the music recorded from the middle of 1972 didn’t see the light of day for years – some of it not until the release of the last of Sony’s lavish studio box sets, The Complete On The Corner Sessions, in 2007.

Davis’s bands had been in an almost constant state of flux since his second great quintet (drummer Tony Williams, bassist Ron Carter, keyboardist Herbie Hancock and saxophonist Wayne Shorter) had hit the buffers in 1968. Key to their music of the mid 1970s was a prioritising of grooves, something Davis dug in the approaches of James Brown, Parliament-Funkadelic, Sly Stone and Jimi Hendrix, and which he sought to make the centre of a new kind of improvisational music. The bedrock throughout this period was provided by drummer Al Foster and bassist Michael Henderson. The pair were temperamentally as well as technically suited to the kind of music Davis wanted to make, capable of locking in to beats and patterns and driving them on for extended periods without feeling any compulsion to take a solo or embellish beyond what was necessary. Their contributions – Henderson’s in particular – became the focus of purists’ disdain, but that just showed the depth of misunderstanding of what this band was all about. It was still jazz, in the sense that the music and the philosophy behind it prized a technically grounded exploration, a need to investigate the possibilities of the chords and the beats and the sound-space and try to take it somewhere new. This is what all the great improvisers have always been trying to do, when you break it down to its essence. But Davis seems to have been attempting to pare away the layers of distraction that can become an inhibition to the seamless communication between musician and audience.

His detractors moaned that he had his back to the audience, wondered why he played his trumpet through a wah-wah pedal which destroyed the beauty and purity of his tone, complained that there wasn’t enough soloing from one of the greatest who ever did it. But these were the wrong questions to ask of someone who had stretched all the old rules way beyond breaking point. Plenty of speculation about Davis’s reasons for appearing on stage behind impenetrable and often huge dark glasses, and his very deliberate disconnection from the audience, his repudiation of the trappings of the star, have been advanced over the years – but often, the boxes many people seemed to keep wanting to fit Davis and his music into were hopelessly outdated and inadequate for the task. Thinking about him as a leader, as a star, expecting him to behave as other performers do – these ideas were redundant. This band was all about the art: everything, from composition and set-structure to the intensity of the performances to the sheer volume at which they played, was an exercise in immersing the audience in the sound, overwhelming the senses with musical data, building a new sonic world that the listener has to inhabit and discover for themselves. Putting a smiling frontman up there, genteelly introducing each selection and thanking the audience at the end, would have entirely destroyed what they were trying to create. This isn’t about the people, it’s about the sound. "Listen." There is no room for ego in this music.

Henderson seems to have been the glue that bound the 1972-75 sound together: he was a teenager when Davis spotted him playing in Stevie Wonder’s band at the Harlem Apollo and became the first bass player Davis had ever hired who only played electric bass, making arguably a more decisive break with the music of Miles’s past than even when he first started working with electric guitarists. Legend has it Davis turned up backstage that night in Harlem (though in his contribution to the sleevenotes of the Cellar Door Sessions box set, Henderson dates the incident to a gig later that week at the Copacobana). The awestruck gaggle of musicians, crew and friends parted, Miles walked up to Stevie and said, "I’m stealing your fuckin’ bass player." At that point Henderson – who would carry on working with Motown stars during down time between Davis projects, including periods spent touring with Marvin Gaye – was a teenager, schooled on funk and soul, a disciple of James Jamerson. He didn’t even know who Miles was.

The other members of the band that February night were guitarists Pete Cosey and Reggie Lucas, saxophonist Sonny Fortune and percussionist James Mtume. Fortune was the most junior member in terms of time in the band, having been drafted in to replace Dave Liebman in mid 1974, but was still a player of considerable stature (Liebman plays on Dark Magus, another layer of incongruity considering its release two years after Agharta). Mtume’s array of instruments ran the gamut from rainsticks to congas and an early-model drum machine; his contributions often seep into the gaps between the other instruments but never fill up space for filling’s sake, always adding colour and nuance that helps balance the sound and build bridges between its most disparate elements. Lucas was as comfortable at minutes-long rhythm playing as Foster and Henderson were – he was a vital part of the groove. And Cosey, a Chicagoan who had worked with Chess blues giants Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters, was a lead player the like of which has scarcely been heard before or since. According to an interview he gave to Paul Tingen, one of a bewilderingly small number of scholars to have properly investigated Miles’ music of this period (his book, Miles Beyond: The Electric Explorations of Miles Davis 1967-1991 is an invaluable resource and is essential reading for anyone who cares about this music: it’s no longer available in shops but signed copies can be bought direct from the author at Miles Beyond), Cosey believed he had "developed techniques with which I could play into the spheres, beyond the notes that are on the guitar neck. I was playing into space." The claim sounds like substance-addled musobollocks of the first water, until you listen to Cosey’s contributions to Agharta, Pangaea and Dark Magus – whereafter it seems hopelessly, frustratingly inadequate.

Unsurprisingly, the new music the band played in Osaka included some of the ideas they attempted to get on to tape. If you had been in the studio during the handful of sessions conducted after 6 June 1972, when the last bits of On The Corner were laid down, you might have recognised quite a bit of the material Davis and the band played on stage that night. But there were probably no more than two dozen people in the world who had heard that stuff on 1 February 1975, and seven of them were on stage. There were bits that might have been familiar to anyone who’d bought Get Up With It (though that album, released in the US in November ’74, didn’t come out in Japan until the following year, and it is unlikely many in the Festival Hall would have had a chance to become familiar with it by the day of the gigs).

Everyone else – that is, pretty much everybody – would have had good reason to be bewildered by the majority of the music being played. No two sets were ever exactly the same, but neither were the performances unstructured or chaotic. The band knew exactly what they were doing, but there was no pre-planning about what changes would happen when. They would take their cues from Miles, who would tell them when to change tack, and what piece of music to segue into next, by playing deft little musical cues or by physically signalling to cut off certain passages and start others. There are tiny moments where something familiar eases itself to the surface: the opening of Agharta‘s ‘Interlude’, where guitars and bass spit out that tense, uneven, staccato rendering of the riff from Sly’s ‘Sing a Simple Song’ which McLaughlin had stuttered through on Jack Johnson; the near minute in the middle of the same piece where Henderson decides to play the bassline to A Kind of Blue opener ‘So What’; or the single appearance, around the 13-minute mark of Pangaea‘s first half, ‘Zimbabwe’, where a guitar (Lucas’s?) lightly plays four chords that seem to echo In A Silent Way‘s ‘It’s About That Time’. They’re welcome reminders that we haven’t quite left our planet entirely – but recognising them isn’t a necessary precursor to active involvement with or absorption within this vast expanse of strangeness.

In any case, whatever confusion the audiences present that day felt would have been an afterthought when confronted by the sheer physical experience of these pulverisingly loud and very visceral performances. They had the visuals and the haptics to help make sense of the audio. The confusion that faced listeners once the music was released was of a different magnitude entirely.

In terms of making sense of what’s going on, it didn’t help that Davis had, for some years by this time, taken to structuring his sets as long medleys, with no breaks between different songs, and none of the conventional signposting that audiences steeped in the jazz, rock, pop or even classical traditions are accustomed to expect. Worse, when the albums emerged, the sets were given arbitrary titles that bear no real relationship to the music performed. There are four ‘tracks’ on Agharta, called ‘Prelude’, ‘Mayisha’, ‘Interlude’ and ‘Theme from Jack Johnson’. Let’s for now ignore the fact that ‘Interlude’ and ‘Theme from Jack Johnson’ are mistransposed (each is in fact the other), and let’s also forget that the original vinyl release split ‘Prelude’ into two. While we’re at it, we’d be well advised to disregard that when Bill Laswell was given access to then-unreleased 1973/4 studio recordings to create his Davis remix album Panthalassa in the late 1990s, he found a studio version of a segment from the Agharta set and called that studio track ‘Agharta Prelude Dub’, but when the music was released for the first time in the The Complete On the Corner Sessions box it was called ‘Turnaround’ – despite the musicians in the band having informally called an entirely different piece of music ‘Turnaroundphrase’. We have to ignore all that, because it’s only by forgetting it that we can start to get close to what’s going on in the music.

All that complication becomes a barrier. We don’t really know the material Davis and the band were playing, and it isn’t presented in a way that coincides with our expectations; at the same time, it sounds unlike anything we’ve heard before. We have no frames of reference that are applicable, and are unable to classify the work according to our established taxonomies. We lack not only a map, but also a functioning compass. Therefore we conclude that this is ‘difficult music’, that these forbiddingly long chunks of improperly named, barely navigable, often very abstractly shapeless blocks of sound have been built into walls so high we cannot climb them – so daunting and monolithic we can only stand awestruck in their presence before retreating to the comforts and securities of three-minute songs with recognisable hooks and names that relate to the images the tunes conjure or the lyrics a vocalist weaves in and around the tune.

Instead, what we should be doing is taking the clues we’re given, and finding new ways to think and to hear and to listen. The title ‘Agharta’ apparently wasn’t of Davis’s choosing, but it’s an interesting and potentially helpful idea: a mythic subterranean kingdom, a whole world we’re unaware of, going on somewhere deep below. Pangaea, too, is a useful cue – as is ‘Gondwana’, the title of the second half of the performance (that album is divided into just two tracks, each over 40 minutes long). Both are names given to vast pre-contenental land masses in the age before Africa and the Americas drifted apart. Laswell’s remix album carried on the tradition: Panthalassa was the ancient sea these supercontinents existed within. So how can we respond? Like strangers trying to make sense of a lost continent, or mariners cut adrift on an ancient ocean of sound, we need to take some time to get our bearings, then we start to explore. So what if there aren’t any signposts? We can make our own. Draw up new charts, if we must – though this is music, not a maze. We’ll always be able to find our way back to where we started.

And then, finally, we’ll maybe get to grips with what this music might mean to us, why it might matter, and find out whether we care or not. Just as the musicians had to display supreme feats of concentration, physical endurance and a ruthlessness when it came to paring back the self and subsuming the individual to the service of the collective, so we as listeners have to steel ourselves to undertake long and unusual journeys, and have to be prepared to listen in a way we’re not individually used to or culturally trained for. That’s not to say that there isn’t great value in picking the things apart and trying to understand them that way – Tingen and his collaborator, the unusually dedicated Davis discographer Enrico Merlin, have provided an invaluable gloss on what’s going on inside these records which adds immeasurably to the ability to grasp the plan and understand the context for, and the nature of, these still shockingly futuristic and unequalled sounds. But it’s entirely possible to get absorbed by this music and to become enthralled and excited by the vast possibilities it demonstrates, and the even vaster ones it points to, without having to become its cartographers.

As Sony’s Bootleg Series of Davis live box sets progresses, one sincerely hopes there’s something spectacular being lined up to honour the 1975 vintage band and deepen our perspectives on the music they built anew, every night, always the same way, always ending up with something entirely different. Bootlegs exist of other gigs from that Japanese tour, as well as of shows back in the States later in the year, some of which are reckoned to be better than Agharta and Pangaea. An official release for as many of these as decent-quality recordings exist of would satisfy listeners approaching this music from both traditional and non-traditional routes: an extended immersion, complete with the usually detailed sessionography and scene-setting booklet notes the series delivers, would help demystify this astonishing music and place it in an enhanced and broadened context – while those who crave this music of excess would simply delight in being able to immerse themselves in even more of it.

In the absence of a super-size, properly curated helping of the ’75 Davis band, what’s the best route in? That, of course, will depend on your perspectives and predilections. The generally held view seems to be that Agharta is the best of the three live albums; Pangaea, still excellent, is reckoned to be its slight inferior, in part because Davis, not really up to the rigours of two such demanding performances in a single day, is less audibly present. Dark Magus is usually put in third place, its critics bemoaning its stark and sometimes monochrome tone, and the distinct spikiness of the second half, where third guitarist Dominique Gaumont has a tendency to dominate. Personally, Dark Magus is my favourite, probably for many of the same reasons others are less smitten. I was five years old when it was recorded and didn’t hear it until this century, after growing up on a diet of The Fall followed by hip hop; its relentlessness and ferocity as well as its single-minded pursuit of the occasionally terrible, often powerful beauty to be found in cycles and repetition give it an edge that has been slightly knocked off by the time the band made the other two albums in Japan. It also is the only one of the three to include a track Tingen and Merlin call ‘Funk’, which opens the second section of the four (a medley the sleeve titles ‘Wili’), where Foster and Henderson lock into a bass-and-drum riff so humungous you have to keep listening simply to know how on earth any other musician could manage to ride on top of it without being thrown off and trampled under its cavalry’s worth of hooves. But the best advice is to hear them all.

It all comes back to Miles, and to that one word that Quincy Troupe chose, out of the hours of conversations that became a friendship as well as a book, to open Davis’ autobiography. Don’t be afraid. Dive in. This is some of the most adventurous, committed, spirited, inventive, beguiling, consciousness-expanding, exhilarating, and exciting music ever made. There is only one instruction:

"Listen."