Come, comrades, come, your glasses clink; Up with your hands a health to drink, The health of all that workers be, In every land, on every sea.

‘Down Among the Dead Men’ By William Morris from Chants For Socialists

It was Billy Bragg who inspired Essex-born pop polymath Darren Hayman to pick up the guitar. "Seeing him live in the Eighties had a big influence on me," Hayman says. "Left-wing music and politics seemed to belong together at that point, much more than now."

Now? "I feel that music now isn’t really political very often. There are some artists…" he says with a jerky swipe at his fringe and nudge of his glasses. Talk politics with 44-year-old Hayman around a massive polished wooden table in William Morris’ Kelmscott House in Hammersmith and it’s not long before Hayman recalls his teenage years consumed with both left-wing politics and music. Even better if they were combined, as in the case of Bragg and the Red Wedge collective of musicians, which included Paul Weller’s The Style Council and Elvis Costello.

Things have now come full circle for the lanky rocker. After tabling his lefty leanings, the past few years have seen Hayman embark on some unusual historical journeys through music which are light years away from his Hefner-inspired indie pop stardom. These journeys in time and sound have yielded solo albums of conceptual and historical brilliance – whether it be unearthing 17th century English Civil War songs, researching Essex witch trials or the startlingly effective documentation of the fate of London’s lidos through music and field recordings.

However, his marriage of art, history, politics and music has now reached a most triumphant climax on his new album, Chants For Socialists, based on an incendiary pamphlet by Arts & Crafts legend William Morris.

Set for release on February 2 on West London label wiaiwya, it was an ambitious project that owes more to chance than design, as Hayman readily admits. He only stumbled upon a photocopied version of Morris’ Chants For Socialists pamphlet as he ambled around the William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow. Living just around the corner, he admits that he was certainly aware of Morris as an artist and a craftsman, but not so much as a political agitator.

"The project started about three years ago, and I worked on it sporadically," Hayman says. "But as soon as I picked up Morris’ pamphlet, I loved how immediate and divisive it seemed. And I liked the idea of seeing it in a record shop. It seemed to set an agenda. And it reminded me of that time when I started buying records."

His attempt to make 19th Century political chants relevant for 21st Century ears has been largely successful. His rousing take on ‘May Day 1984′ shows just how much work he’s done to make Morris’ songs his own by taking the original opening line of:

"Clad is the year in all her best/ The land is sweet and sheen/ Now Spring with Summer at her breast/ Goes down the meadows green"

and transforming it into:

"Dress the year in her best/ Spring with summer pinned on her dress".

Trimming its ten long verses down to six pithy ones while throwing in an anthemic chorus sees Hayman come impressively close to the rallying call that Morris might have envisioned, albeit with a Pavement-style slacker rock vibe thrown in for good measure.

"My previous attempts at political songs have been gauche and bratty," he admits. "It’s not a form that suits me, but I hope my politics are apparent from the character and sentiments in the songs. However, it was very slow work and it wasn’t easy.

"Sometimes I would just have the pamphlet sitting on the arm of the sofa as I watched TV and I would half look at it. They are long, really long songs, with many verses. Morris also wrote them in a very idiomatic style making it difficult to extract their meaning. It was usually to do with where the verb or noun sat in the sentence, but thankfully my wife is an English teacher and she helped me decode them.

"I then had to decide how much I wanted to adapt them to make the language more accessible, or whether to make them as true to the original as possible. Of the ten songs, I managed the arrangements for eight. For the other two, I admitted defeat and needed fresh ears for the task, so I called in friends to help."

One of those friends was Robert Rotifer who arranged the lush, and impressively dark, version of ‘Down Among The Dead Men’. Aside from uncomfortably stretching Hayman’s vocal range at times, the chorus-heavy tune is positively macabre, with Hayman intoning: "Now, comrades, let the glass blush red/ Drink we the unforgotten dead".

Hayman points out that the top of Morris’ pamphlet it reads: "Agitate and organise". But he admits that he didn’t want the album to be just a "rallying call or a manifesto". "I wanted it to be a comfort to people like me, maybe those of us who used to be a little more engaged in politics," he reflects. "It reminded me of my teenage years when I was more politically active than I am now. So in a way, I wanted it to be a comfort or a solace for lefties. Perhaps it should have been called Lullabies For Socialists?"

Eventually, the lyrics were hammered out, arrangements settled upon and the songs emerged. Then Hayman, with the help of wiaiwya’s John Jervis, set about putting the ‘social’ into socialism. "So I invited strangers from Walthamstow to come to the gallery and sing the songs," he says. "It wasn’t about ability. Anyone was welcome. For me socialism is about community. The results were fantastic and usually in the studio we just overdub and multiply the voices for a chorus. But it doesn’t really work. It’s different. So it was great to have 30 or so different voices singing the songs in Morris’ childhood home."

Sensing he was on a roll with the project, Hayman kept doubling down on his Morris mania. "I very rarely record in studios these days," he says. "There is so much technology available. So I took the idea further and discovered that Morris had owned a piano which was in Kelmscott Manor in the Cotswolds. It was broken and worn out, and I was made to wear gloves to play it, but you could still get a tune out of it. Barely."

And finally, it was a trip down the Thames to Hammersmith to Morris’ final home, Kelmscott House, that saw Hayman produce the finishing touches to the album. Today, the house is home to the William Morris Society. But in Morris’ day it was a hive of industry. Morris held meetings of the Hammersmith Socialist League in his coach house – where Gustav Holst once conducted the Hammersmith Socialist Society Choir – and made books and prints with his Kelmscott Press in the lower ground floor of his house, which he used to create a legendary edition of Geoffrey Chaucer’s writings.

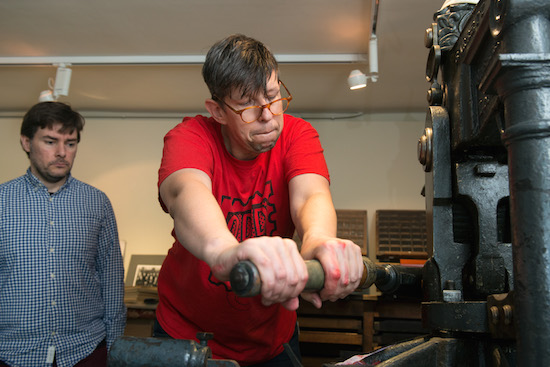

Hayman used the coach house to record more vocals with current members of the Hammersmith Socialist League and used Morris’ press to print the 500 jackets of Chants for Socialists LP with the help of a Twitter-sourced band of volunteers, who cranked out covers while answering questions from puzzled Arts & Crafts enthusiasts and tourists.

With hands still covered in ink from his shift on the press, Hayman admits that he enjoyed making a connection with Morris’ lyrics, the historic locations and his messages. "I don’t think of myself as clever enough to write anything other than songs," he says with a wry smile. "But I like songs having non-traditional subject matter or content rather than just boy meets girl.

"Morris grouped these songs under the banner of socialism and I class myself to be a socialist. But these songs to me are about simple expressions of kindness and hope. I acknowledge their naivety and rhetoric.

"They offer few practical solutions for today, but I love their simplicity. They make me feel young again. They remind me of the hope I had in the Red Wedge movement, and how politicised I was around the 1984 miners’ strike."

That "simplicity" is reflected in the concise arrangements of the songs, and kindness in lyrics such as on ‘The Day is Coming’ as Hayman plucks and sings: "The day will come when we will work and rejoice/ In the deeds of hands/ The day will come when we get home content/ Too tired to stand."

It’s one of the more gentle songs on the album and shows Hayman’s skill for making a lot out of a little, with the dreamy, if strident, chorus of ‘We will it’ striking a chord. "I imagine these lyrics, preserved in a case labelled ‘break glass in case of emergency’", Hayman says. "And I think we live in a time of emergency."

It’s been a surreal and remarkably wet October morning talking to Hayman. While the steady hand-pulled clunk of the press continues in Kelmscott House, I set off for home walking under the busy A4 only to re-emerge at street level into the middle of the St Peter’s Church harvest festival. Morris dancers pound the streets, rains batters the merrymakers, parents press apples into juice under soggy marquees, and the vicar sups ale with the local MP.

Here is a world that Morris would recognise in its quintessentially bizarre Englishness. It may be a world away from Hayman’s biting satire and unfailing ear for melody, but both messengers share a celebration of the profound nature of what the collective can achieve armed with just their bare hands and guile.

It may be best described by Morris himself in his 1894 essay, How I Became A Socialist, as he writes: "It is the province of art to set the true ideal of a full and reasonable life before him, a life to which the perception and creation of beauty, the enjoyment of real pleasure that is, shall be felt to be as necessary to man as his daily bread."

Darren Hayman plays a special acoustic set of his Chants for Socialists album at the William Morris Society in Hammersmith on Saturday, February 7, at 2.15pm. A Q&A session will follow. Tickets: Members £6, non-members £8, students £4