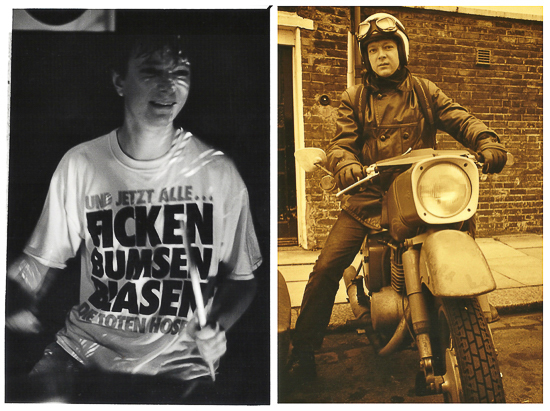

Joe drumming with Th’ Faith Healers at the Square, Harlow (1991), outside Joe’s flat on his 1972 East German Army MZ ES 250/2A, Camden (1994) Photography by the author

Photographer, drummer and man about Camden Town on an East German army motorcycle; Joe Dilworth was always going to be a hero to my younger self. In the early 1990s, not only was he behind the camera during the glory days of Melody Maker; documenting many of the bands who played and drank near his Camden home, he was also the relentless rhythm engine to my favourite band, Th’ Faith Healers, and the original drummer with their Too Pure labelmates Stereolab.

Joe’s photographic portraits were always stylishly composed or casually candid, while his live photography gracefully caught the bold and the beautiful on prints that framed each image within confident keylines. Among those he photographed included the first portraits of Saint Etienne (co-founded by Maker colleague, Bob Stanley), whose first album, Fox Base Alpha, wrongly credited Joe for its cover photograph though it did feature the wistful, ‘Dilworth’s Theme’; and My Bloody Valentine, creating the ambiguous, overexposed portraits that defined the visual representation for their breakthrough album, Isn’t Anything.

At the same time, Th’ Faith Healers played immediate, tuneful noise built on irresistible Krautrock grooves with playful song titles like ‘Pop Song’, ‘Gorgeous Blue Flower In My Garden’ and ‘Reptile Smile’; the lead tracks on their first three EPs. It wasn’t sophisticated but it was a hell of a lot of primary colour fun with enthralling live performances that connected with their audience. Whether it was their original songs or cover versions that hit the heights of Can’s ‘Mother Sky’, what appealed to me was how grounded they remained. Like Joe, guitarist Tom Cullinan (later of Quickspace) and bassist Ben Hopkins were unassuming, clean shaven guys, while singer Roxanne Stephen projected hippy chick fun with a smile that beamed from under her waterfall of cascading hair.

Their London gigs may have attracted Th’ Faithful; their devoted, manically laughing, adolescent fans who decorated, swayed and ‘lurched’ with them on stage, but these spiritual workers were the real deal who John Peel invited to record six BBC sessions. Meanwhile, when music appeared to cross the Atlantic in only one grunge-based direction, Th’ Faith Healers attracted believers in America where they supported an early line-up of the Breeders. They also charmed the notoriously skeptical magazine, Your Flesh, who declared that their 1992 album Lido was "truly wide, worldly and wacked… this is one of those pivotal, crucial, influential, album-of-the-year type things", while the New York Times observed that the band "find frenzy, primal release and euphoria in repetition… like a sudden turn by a bullet train".

As a fan turned friend, I was fortunate to have stayed on occasion at Joe’s flat after gigs. Not only was its Camden Road location convenient but inside there was an assortment of cool objects including stacks of medium format negatives and photographic prints from his travels in Eastern Europe before and after the Revolutions of 1989. In the lounge where the photo session for Isn’t Anything was shot, pieces of lighting equipment, drum kit and motorcycle engines lay still as if waiting to spring into Fantasia-like life, while his bathroom doubled up as a darkroom with an enlarger, stacks of trays and containers of photographic chemicals.

I had wanted to interview Joe for my fanzine, Quality Time, a live photography, cut and paste collage affair that I first printed in 1991. However, when Th’ Faith Healers released Imaginary Friend, their anticipated second album in 1993, it lacked the immediacy and vibrancy of Lido and their live shows. More significantly for me, I hadn’t felt ready or brave enough to ask until just before their demise.

In March 1994, the band closed the second night of the PIAO festival, a two day festival organised by the band Linus at a community centre in Hammersmith. The event was a landmark gathering of over 30 bands including Prolapse, Heavenly and Mambo Taxi alongside early performances by Hood and Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci. For Th’ Faith Healers though, their set with Prolapse’s Linda Steelyard deputising on vocals was a fateful one, as weeks later, they closed their ministry.

In the weeks in between, I interviewed Joe at his flat where he was developing films in his bathroom and though I wasn’t to know it then, the band’s future was clearly under consideration. By the time my second issue was printed two years later and with Th’ Faith Healers being no more, I dropped the interview that I had also struggled to place in context. It wasn’t until 20 years after our conversation that I felt ready to return to the interview and forwarded a draft to the interview’s unsuspecting subject. Joe replied how fascinated he was to read what he had been thinking back then ahead of his next moves.

During the years bridging the millennium, Joe took on promotional photography commissions for Franz Ferdinand, the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion, Goldfrapp and Nick Cave among others. He also photographed and toured as second drummer with Add N to (X); one of over 20 bands that he’s played with including Spiritualized and the Hangovers with The Raincoats’s Gina Birch. Perhaps inevitably though after further long stays in Eastern Europe, Joe moved to his spiritual home in East Berlin.

However, before going back to the future of 2015, during the interview Joe describes how a photographer "can come back to a negative years later and approach it completely differently". As a premonition for this revived piece, it highlights how the past can be looked upon in a new light.

Camden Town, 1994

So what came first, the drumming or the photography?

Joe Dilworth: The drumming. I started a band at school with friends and we were together for quite a while.

Was that the pre-Camden scene?

JD: That was the Kentish Town scene, I guess. There was a lot of bands around here, kind of late 70s, early 80s; [with an] average age of about 15.

Where did you pick up your drum technique? [As a one-time drummer myself, I wondered about Joe’s unique style for not crossing his hands, GN]

JD: Well I’m left-handed but I didn’t know how to play drums. The kit was set up right-handed when I bought it, so I don’t cross my hands over. It makes it difficult to do some quite ‘drummerly’ things and quite easy to do some ‘un-drummerly’ things.

I played in a jazz band for a couple of years. That was fairly anarchic stuff but taught me to play a bit looser, a bit quieter in some ways as well. The thing about being a drummer is you get to play with people who are really good because there’s always a shortage of drummers. The lot I fell in with were really excellent musicians and a real laugh as well. They didn’t mind and they let me play. Although I was still playing the drums when I got interested in photography, I was never really in another band until I joined Th’ Faith Healers.

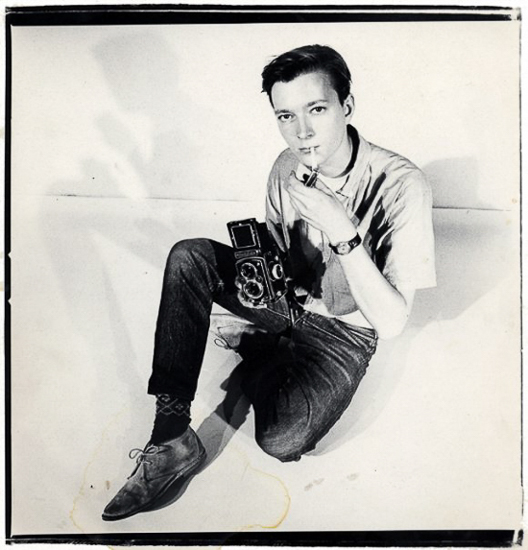

Joe with Rolleiflex, London (1984) Photograph by Steve Pyke

So how did you get into photography?

JD: When that band I was playing in split up, I was so pissed off with having to rely on other people for what I was doing creatively that I thought I would do something on my own. A friend of mine, Steve Pyke [A motorcycle enthusiast and musician turned staff photographer for the New Yorker – GN], used to be a postman and lived around the corner. He was just getting into taking pictures. I really liked his stuff and thought that would be something that I’d enjoy. I started looking at photographs; especially 30s French and Hungarian stuff. I started to get a feeling for it and the idea of being able to capture something. Stuff that really happens.

Isn’t that how a lot of people start by wanting to capture things as they actually happen?

JD: Well there’s no way you can. It’s all a lie because it’s so subjective. It’s all the way you

personally approach it. You are only showing your own little personal version of reality, which

will be completely different to everyone else’s. That’s what’s interesting because although it is just light on ‘real stuff’ – the fact that it’s thought of as real, so therefore it must be something that’s actually happened – [that] gives it an air of otherworldliness. Like you haven’t really created it, it’s just kind of happened.

But you can also do that by applying practical methods.

JD: Yeah that’s true. There’s always another way to do things, especially with black and white. It’s only ‘light and not light’, ‘stop and go’, ‘developing and fix’. It’s a positive and negative process so you can work out all the different ways of affecting the end result. Your approach will change how the picture ends up. So you’ve got to have an idea when you’re taking the picture of all these other processes you’re going to go through before you end up with the real finished photo and I really like that.

Do you find it easy to fuck up now?

JD: I do get into habits but they’re usually bad. Every now and then, I take a look at something I’ve done a while ago and think, ‘How the hell did I do that?’ [Over time] I tend to put on a bigger and bigger safety margin until you’re really ruining the negatives by totally overexposing and overdeveloping. It’s a terrible habit and I’m trying to get out of that. One day I’ll have a proper darkroom and I won’t have to do all of this fannying around. Working in the bath isn’t really ideal for this.

What kind of things do you like taking photos of when you’re not doing bands?

JD: I like just the way the light acts on plaster or the way that people stand on street corners. Just little incidents that happen that mean nothing, but everything at the same time.

Can you explain your approach to photographing bands where you seem to line up faces together within a wide angle?

JD: Sometimes when you don’t get much time, to get a band’s attention you’ve got to be close to them. Close enough to be able to reach out and touch. When you’ve got them all there it’s like you’re in a huddle and then you can try and get something from them in that five minutes. I did a thing with Moonshake [Th Healers’ labelmates] and that wasn’t like that at all because we had the whole afternoon and it was like sitting around [here] in the front room. I ended up not moving them around that much, [and taking photographs of] just how they were sitting. Just talking to them and trying to get something different, a bit more relaxed.

Do you take better pictures of people who you know’?

JD: Yeah and that’s the only stuff I do these days. Often with the Melody Maker, I was taking photos of people who I didn’t even know the music. That didn’t seem to make sense at all. I’d much rather go see a band and think ‘Right! I want to do your pictures!’

So how did photographing for the music press happen?

JD: I didn’t intend to get into the papers at all but I needed the work. It’s good because you have to work really fast and there’s a lot of pressure but it is interesting to do. When Melody Maker was really big [in actual page size], we used to have a lot of pictures in it. You’d be doing three or four jobs a week, taking the pictures and [developing and printing] them in the same day. Then when the paper comes out, it’s like, ‘Oh yeah, I’d forgotten about that!’ And there’s that whole kick of having stuff you’d done in print.

Does it pay?

JD: If you’re doing it all the time. I did live off it for a long time and I still do. I get some money from the band but it’s difficult when we’ve got to spend a lot of time doing other things, so I have to turn down a lot of work. I’d like to be doing other things and getting into another area of photography. Although I took all these pictures in Switzerland when we were on tour, I’ll have to get the Moonshake job I did yesterday finished. It’s difficult doing something you do for pleasure for your living as well. It’s hard to give time to do things you do for yourself.

When you’re actually printing, do you find that after putting all the effort into the planning that you give up because it’s not important anymore?

JD: Yeah, but you can come back to a negative years later and approach it completely differently because you’ll be thinking in a different way. I do like printing but it takes a lot of concentration. I haven’t done a lot lately because it means really having nothing else on that day. It’s like today, I was going to stay in and print and now I’ve got to go out to see Too Pure and stuff like that.

Do you ever think about all the time that you actually spend taking photographs that you might be doing something else?

JD: No. I think more about the time that being in a band which is like 10% doing something and 90% waiting for something to happen.

So has the band held you up from your photography?

JD: Probably, yeah, but you can’t do everything all of the time. I wasn’t too sure about the direction to take. I was getting a bit bored of working for the music papers although I’m still doing that to a certain extent. It’s good to be on the other end [of taking photographs].

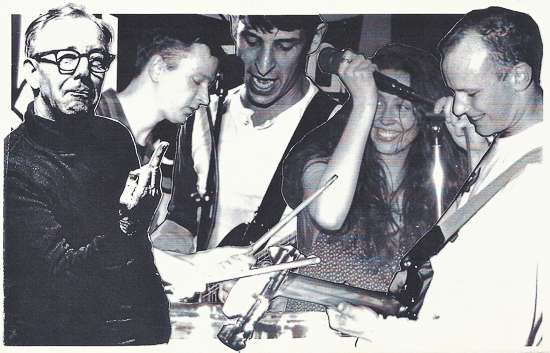

Th’ Faith Healers, Quality Time-style (l-r the Professor of rude gestures, Joe, Tom, Roxanne & Ben – photography by Greg Neate

How long was it then before Th’ Faith Healers came together?

JD: Ben and Tom and this other guy, Tony, were playing together at the end of ’87. I used to go and see them and when Tony left, I joined. It was just to do a couple of gigs and have a laugh. It was more just to annoy people really than anything else. I think we achieved that aim!

The whole thing was to be more than what was happening, which was a lot of jangly stuff. Some of it was good but the vast majority of it was totally lame and the whole idea was to do something totally ‘un-lame’, by being very loud and very repetitive. That was the original thing.

[For a more extensive account of music in Camden at that time that includes how Th’ Faith Healers secured their first gig at the Camden Falcon, see Those Tourists Are Money: The Rock And Roll Guide To Camden by Ann Scanlon, if you can track down a copy – GN]

But you’re not actually aggressive or appear like what you’d associate with loud music.

JD: At the start there were people and other bands in a hardcore scene who really hated us because we weren’t ‘proper hardcore’. It’s like, ‘Good! We’re not trying to be. We’re taking that stuff away from you!’

What I also like is the constant flow you get in dance music where songs with the same beats per minute are mixed together.

JD: Yeah, That’s another influence on us. My influences are drum machines and the way that people think about drumming, not as drummers, but as ‘Right, this loop works.’ The way it changes the more you do it, rather than putting bits in or playing around with it. That’s what somebody who isn’t a drummer is doing; a drum patten will just keep going. Electronic music, a big influence on us.

And it works live, where you can lose yourself in your music. I’ve spoken to people who haven’t seen you before are they’re impressed by the way they’ve been drawn into it.

JD: Right! That’s the thing that good dance music can do. There’s that whole feeling of

getting totally lost in what we’re doing. If you’re trying too hard, you can completely blow it. That’s why it’s best unplanned; sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. There’s no point in us rehearsing stuff like that because it only works with an audience. So you’re watching them, seeing how they’re reacting to it and trying to work with them.

Joe at work recently with Cavern Of Anti-Matter, live in Berlin, 2013

It’s great the way you can just turn up, plug in and raise the atmosphere, like at PIAO.

JD: Good! That’s what that European tour was like because everything got so fucked up. We had one soundcheck on the whole tour. We just arrived, put the gear on stage and played. That’s really nice to be able to do that without hanging around; [it] makes it more fun!

So how come you’ve lasted while the Loveblobs, Milk and now Silverfish (all London-based bands that Th’ Healers previously played with – GN) have split up. You’re the only ones left!

JD: Yep, or they’ve gone on to mega stardom. We played with all these bands when we started out like Teenage Fanclub. It’s that long ago that they’re either dead and buried or up there in the stratosphere.

It’s a shame that bands like Sun Carriage have split because it seems as if the music scene [post Nirvana’s Nevermind – GN] is more suited to them now.

JD: Absolutely! When we were in Europe, it was amazing how many people knew Sun Carriage and the Loveblobs [a short-lived band on Wiiija records that included drummer, Tim Cedar, later of Part Chimp, Hey Colossus and Sex Swing – GN). There are bands in Belgium covering Loveblobs songs and going ‘Oh, what are they doing now?’ If they put out those records now or if they’d gone to America. It’s just weird how we got those breaks and they didn’t.

That doesn’t mean it’s been all hearts and roses by a long chalk. So many times I felt like jacking it in and we’ve been on the edge of thinking ‘Oh, I’ve had enough of this!’ I stick with it but having said that, there’s no point in saying it’s going to go on forever, because it obviously won’t. When we’ve done our bit we’ll gracefully step aside.

Could you do any more stuff than you actually do?

JD: I think it’s quite good, I mean we’ve done so many Peel sessions and they always seem to come out pretty good. It’s generally when someone pulls out. They ring us up at short notice and we just go in, write a couple of songs and do it. If we can do that then we should be able to do more stuff. I just think we’re incredibly lazy as a band, very slack.

As a photographer, can you explain how the record covers look so bad [despite Joe’s photography talents, Th’ Healers sleeve designs always appeared rough and unstylish – GN] to begin with but they make sense in a couple of years?

JD: Well, it’s always a last minute thing but in the end the cover just becomes connected with the record that you can’t separate them

The impression looking at the records and the lettering is that you’re quite embarrassed about doing it.

JD: I think I’m embarrassed about a lot of stuff to do with being in bands and the stuff that goes with it.

So explain your interest in motorcycles.

JD: I just don’t like travelling around with a big group of people. It just grates and I’d rather be doing it on my own. It’s like travelling around in a transit [van], I don’t like it. Motorcycles just intrigued me. It’s one of those things that people tell you are a really bad idea so you think ‘Oh, alright then, I’ll give it a go.’ It’s almost as stupid as taking up smoking at the age of 25. I don’t know but it’s a great way to get around London.

It would makes me shit-scared.

JD: That’s the whole point. A friend of mine, who’s as straight as a bastard, just got one and he’s so scared of the whole thing. It’s like, well don’t have a motorbike because that’s the point. It’s a calculated risk. You’re taking your life in your hands and seeing if you can deal with it but if you have the confidence, then you will be alright. If you’re so worried about dying then there’s no point in living anyway!

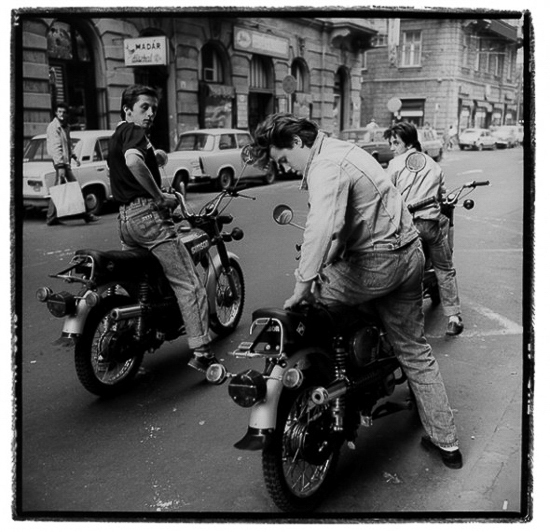

8th district, Budapest ’89 photograph by Joe Dilworth

Margate 2014

Three young men stand astride stationary motorcycles pointed in the same vanishing point direction as the cars that line the far side of the urban street. Each wears blue jeans without leathers or helmets. In the foreground, the guy with George Michael hair steadies himself and climbs aboard as the other two watch and wait for their friend. As a square black and white image, it’s a timeless portrait of young men and their machines without any indication of the city’s revolution that year. Nevertheless the historic European street, the fashion, their 50cc Simson S51 motorcycles and the Trabant cars are consistent with the photograph’s label; 8th district, Budapest ’89.

That scene is now the lead image for an exhibtion of Joe’s late 80s and early 90s Eastern European photography. While Vortigern Margate could be mistaken for being in Germany, this one-room gallery is in the far east of Kent. Gallery owner and fellow music photographer, Jamie Beeden, has just opened the exhibition space in Margate to promote the work of contemporary photographers. Having been friends and had access to Joe’s archives from which a much larger show could have been made, Jamie has curated ten prints for the aptly named, Time Travel.

Two days before Christmas and Vortigern Margate has specially opened for a guest evening with the photographer. The room is full of admirers who remain behind after Joe had described his experiences and which he summarises in the exhibition’s blurb:

"There was a feeling, growing up in London during the 60s and 70s, that it was a place of departed giants. That like Britain after the Romans left, we were camped out in the ruins of a great city.

The first time I went behind the ‘iron curtain’, I found that feeling still there, public space bearing the scars of its history and similarly under-populated… as a photographer, I felt like I was looking at my own childhood. The lack of advertising, street furniture, and traffic meant a simple visual landscape, on a more human scale. And of course, that fact that I wasn’t really allowed to be taking the pictures I did, gave it an extra appeal."

After warm greetings on a chilly night, I ask did he ride here tonight? Sensibly Joe states he took the train though he still has three partly assembled motorcycles in London where he’s back visiting family. As we catch up, we discuss his experience of street photography with a Rolleiflex, the German made camera for medium format negatives that has gained new interest following the ‘discovery’ of the work of Vivian Maier; the intensely private American nanny whose street photography only became known after her death in 2009.

When shooting with a Rolleiflex, the photographer prepares their composition by looking down though the camera’s viewfinder that is typically held above the waist. This approach, says Joe, is more collaborative as the photographer’s face isn’t blocked and it invites the subject to take part. Although I’ve never used a Rolleiflex, I suggest that the position of the camera lens that’s held at a child’s level of vision, may also account for the feelings evoked in the viewer. This observation resonates with Joe, who considers Th’ Faith Healers’ music to have been about childhood, as represented by the beach holiday camp scene on the cover of Lido, which was lifted from a postcard of the Italian resort where Joe visited as a child with his family.

While Time Travel at Vortigern Margate runs until January 14, it’s just one of Joe’s current activities and may precede what could be his most productive year yet. On January 5, Joe and business partner, Thomas Gust, began the process of opening Bildband Berlin, a dedicated photography bookstore in Germany with a gallery space for guest photographers. In addition, Joe is working on two photography books from his travels in Eastern Europe and his music photography respectively. Meanwhile his current band, the Berlin-based, Cavern Of Anti-Matter (formed with former Stereolab bandmate, Tim Gane and featured on the Quietus this week), are due to release their second album this spring.

On looking through the prints for sale at Vortigern Margate, a number of them are familiar from over 20 years ago at Joe’s flat. While many of the framed prints on display are of empty street scenes, a separate print that’s stored within a box of prints stands out for the dynamism involved. A woman’s left hand restrains a figure wearing a military-style jacket, who reaches upwards with authority. The man’s hand obscures his face but closer inspection reveals a crude tattoo on his chest and that he has no shirt on underneath.

8th district, Budapest ’89 photograph by Joe Dilworth

Like the young motorcyclists, this photograph was taken near the same time and place in Budapest. Joe recalls that while taking photographs in the area with the knowledge of the soliciting street prostitutes, the man who confronted him was their pimp. Without knowing how it would appear or if he’d be able to keep his camera, Joe took the photograph with his last negative on the roll.

Fortunately all ended well as the case for the English photographer was argued for by the woman in Hungarian. In turn, the man did what any self-respecting gangster would do when faced with photographic immortality; he took up a boxer’s pose and insisted on being photographed. Joe didn’t have time to change rolls but he kept up the pretence unaware of what he’d captured until he developed the negatives back in London. The interaction may have been unplanned but it made for a memorable photograph that as a document can continue to be looked upon with new light.

Joe Dilworth’s photography is viewable at JoeDilworth.com