He’d be entitled to laugh. Lord knows we laughed enough at him.

Mirth was never Matt Johnson’s forte, though. It would be hard to picture him emitting so much as a sardonic bark of vindication. But again, he’d have the right.

Unless you count Burning Blue Soul, originally released under Johnson’s own name, Mind Bomb was only the third album credited to The The, and it had the small problem of following a masterpiece.

If you want to know what Britain looked and smelled and felt like in 1986, you can do either one of two things. You can look at Britain as it is now, and imagine it as not quite so fraudulently glossy on the surface, not quite so ugly just beneath it, not quite so bitterly and impassably cracked along every faultline it possesses – although, at the time, it was hard to conceive it might become more so. Or you can listen to The The’s album Infected. Of its key song, ‘Heartland’, Johnson said on its release this was his intention: future listeners should be able to play it and be transported to where and when it came from. It worked.

Few artworks of any type will ever capture a time and place with the definitive gaze Johnson applied to mid-Eighties Britain on Infected. I borrow a phrase there from one of the likewise rare spirits who might be described as even remotely kindred to him. Where Howard Devoto sang in riddles, parables and allusive nightmare images, Johnson was blunt as a hammer, piercing as nails. You knew precisely what he was getting at, and you knew precisely where he was getting at it: you felt it pounded in though skin and tendons. A crucifixion of a kind. Think I’m exaggerating? Listen to Infected again and see if he isn’t nailing himself to a figurative cross alongside this island Golgotha’s irredeemable brigands.

But that was the album before. He’d done his own country and his own era. What to do next without repeating himself? He fixed upon the world, its geopolitical future, and the fate of humanity as a whole. Whatever criticisms might be levelled at Matt Johnson over the years, thinking small would not be one of them

There was a presentiment of Mind Bomb on Infected, with the opening track on side 2, ‘Sweet Bird Of Truth’. "Arabia… Arabia… Arabia," chants a metronomic crackling voice as if heard over a pilot’s radio set. A USAF plane is descending unstoppably into the Gulf Of Arabia as its sole conscious airman grapples with both existential terror and his conscience: "I can almost smell the blood washing against the shores … Time was when I seemed to know/Just like any other G.I. Joe/Should I cry like a baby, die like a man/While all the planets go to war, start joining hands?"

(Psst – you know what, readers? I think he may have intended that whole sinking American military aircraft thing as a metaphor.)

This, bear in mind, was four years before Operation Desert Shield, and already Johnson saw the American century, America’s global power and America’s global ambitions, failing and falling in a Middle Eastern graveyard. Mind Bomb, which spread itself, lava-like, into a burning lake of foreboding about the West and Middle East, was released a year before the invasion of Kuwait. The second Gulf War, the Iraq War, was still fourteen years away. Matt Johnson was right. He saw it coming. And we laughed at him, the way one does at prophets. Because he’d really overdone the fire and brimstone this time.

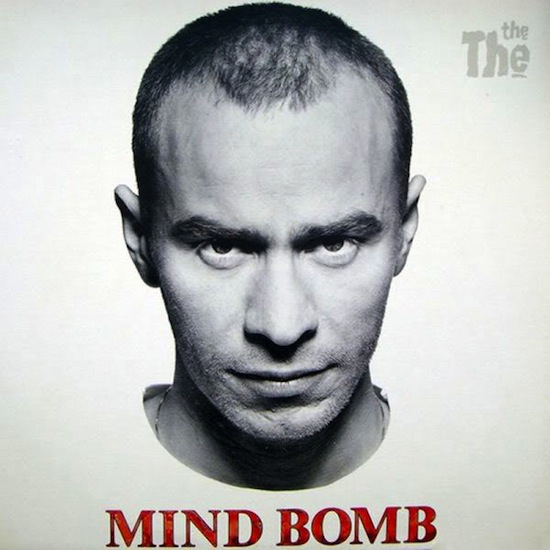

We, or at least I, loved the way he’d overdone it, mind. There he was, a lifesize head glowering off the textured white LP cover above bloody title letters – an Old Testament glower which, if it concealed the hint of a smile, surely did so only to indicate that this crop-headed young Isaiah knew just what dregs stir at the bottom of your filthy soul. Turn it over and there’s a white dove impaled on a bayonet. An actual honest-to-God white dove, for Heaven’s sake. Did I mention the part about being blunt, and piercing? The thing about metaphors is that they aren’t literal, but Johnson had a damned good crack at making them seem that way. I’ll level with you. Even today, that back cover makes me chuckle. As for the rest of it: I’m not laughing now.

If Infected seethed and rattled with claustrophobic urgency and loathing, and it did, then Mind Bomb was slow, expansive, looming into inexorable life with a rage that smouldered rather than flamed. It creeps up on you, on ‘Good Morning Beautiful’, with what sounds like a muezzin’s call, which for one reason and another it’s likely no major label act would dare to use today (although it might be a Qawwal; it isn’t credited and I haven’t the ear to tell.) Next, a blast of sluggish brass over ominous piano chords, and pattering, insinuating percussion. Then Johnson’s voice, a tense, febrile tenor, a voice living on its nerves, near breaking point, teetering here and there into an aspirated growl, sizzling when pressed against the side of the pan.

I KNOW!, That GOD lives in everybody’s souls.

& the only ‘devil’ in your world.

Lives in the human … heart!

That, by the way, is not my interpretation of his phrasing. It’s a transcript of the album’s lyric sheet:

So now ask yourself.

What is human? & what is Truth?

Be fair. You can see why we laughed.

WHO IS IT?

We (friends and I) used to do this bit for a gag, hands cupped over mouth to simulate its Darth Vader rumble. "WHO IS IT, LUKE?"

But the reason it stuck with us in the first place, the reason we did this bit over and over, was because we were listening to it over and over. Because we were transfixed by it. Because it was so powerful. Because it was a great record, created by a remarkable band.

There’s the other thing: the band. Something The The had never been before, on a regular basis. They too glowered monochromatically, from the inner sleeve, although the then elfin Johnny Marr, two years out of The Smiths, looked a touch alarmed the camera might be about to glower back. The line-up – two main men plus a rhythm section to make up a quartet – inevitably recalled that of Marr’s old band, but its Other Two were musicians of notable range, and needed to be.

Bassist James Eller and drummer David Palmer weren’t famous, particularly (the former had played for Clive Langer and Julian Cope, the latter was a member of ABC’s classic line-up), but they were just the men for job, as Marr would have been regardless of his fame. If there’s anything in Marr’s post-Smiths career as good as this, and if his own work on anything since has been as good as it is on this, I’ve missed it. It’s not simply a matter of how different Mind Bomb would be if you took his – by turns – stretched, coiled, wailing, glowing guitar off it; it’s that you can’t imagine anything akin to the same album might have come about without it in the first place.

‘Armageddon Days (Are Here Again)’, a scathing cross between a rockabilly tune and ‘The Song Of The Volga Boatmen’, has the plague-on-all-your-houses quality that marks out Curtis Mayfield’s ‘(Don’t Worry) If There’s A Hell Below, We’re All Going To Go’:

ISLAM is rising.

The Christians mobilising.

The world is on its elbows & knees.

It’s forgotten the message and worships the creeds.

That’s the chorus, performed in the manner of the Red Army Choir. And just in case the point is insufficiently hammered home, ‘The Violence Of Truth’ – dense, scrabbled blues-rock whirling around an organ riff and daubed with mean harmonica – surges in to jab a finger at you and demand:

Why is it that everything in this world we do not understand,

We are pushed onto our knees to worship or to damn?

THOSE ARE THE RULES OF RELIGION

THOSE ARE THE LAWS OF THE LAND

That’s how the forces of darkness have suppressed the spirit of man.

This was fierce, stirring music, and lyrics are written to be heard, not read; but at the time it was easy to think Johnson was being reductive. Yeah, religious fundamentalism is bad. What else is new? A quarter-century on, with Islamists murdering thousands every month, with reactionary fanatics plummeting the Middle East into its own Dark Ages, with an American Right that would like to establish a theocracy of its own in the USA, with even secular liberal democracies abjecting themselves before the idea of faith as something with rights of its own, Johnson’s words don’t seem quite so trite. This isn’t just remarkable music. These are songs which saw coming what complacent progressives assumed was on the way out. That ebbing tide was just the water drawing back before the great wave thundered in. And crazy Matt Johnson, the seer on the hill, knew it all along.

Then, that’s it. You think of Mind Bomb as a political album, or at least, I do. A vision of the coming zealot apocalypse both turning in upon and spreading out from the Middle East, centuries of violence and grievances stirred up through cynicism, dogma, greed and malevolence, then flying out to plague interlopers and denizens alike. But three tracks in and that’s all over. The only overt political comment yet to come is ‘The Beat(en) Generation’, a clodhopping pun, a mild, toe-tapping tune and a caustic lyric, which might have fitted better on Infected (just as ‘Sweet Bird Of Truth’ prefigures Mind Bomb), so much does it feel like a sequel to ‘Heartland’.

The other four tracks look inward – as, indeed, did half of Infected – and with no kinder an eye. Johnson reminds me of the Weimar Republic’s expressionists: George Grosz, Otto Dix, Hannah Hoch. He shares their simultaneous fascination and repulsion with the horrors of a diseased age, and finds no reason to place himself above any of it. On the contrary, his introspection is every bit as savage, merciless and dramatic as his excoriations of the world around him. The two things are of a piece. He, or his protagonist, as a man of his time, is a symptom of that time, to be regarded with no greater sympathy than its other abominations.

The exception comes with ‘Kingdom Of Rain’, a tribute of remarkable sensitivity to a dying love. Again, it feels like a sequel, this time to Infected’s torturous ‘Slow Train To Dawn’, where by now the passion and the anguish have

all spurted out.

(I said remarkable sensitivity, not remarkable delicacy.)

It features one of Sinead O’Connor’s finest performances. It’s a heartbreaker. The knowledge and sad acceptance by the one of the other’s distance, the other of the one’s infidelity.

I just wanted somebody to caress, this damsel in distress.

A companion piece of sorts, ‘August & September’ has something of the chanson about it, and engages in terrible self-laceration. The protagonist is spurned, is devastated, yet still he blames himself for the appalling, selfish crime of wanting his lover back:

I started writing you the letter.

Which turned into the book.

I was going to reach across the ocean.

& force you to look.

But what kind of man was I?

Who would sacrifice your happiness, to satisfy his pride

What kind of man was I?

Who would delay your destiny, to appease his tiny mind.

At which point, one thinks, c’mon, Matt. Even if you’re not entitled to another person, you’re entitled to your feelings about them. This is, I suppose, the opposite of solipsism. The inability to see yourself as a valid human being at the moment you most need to. But Johnson isn’t in the business of self-help or therapy. He’s in the business of spilling blood onto the tracks, and harrowing though it is, it’s also recognisable and real. As a rule, Johnson didn’t so much write love songs as perform surgeries, unanaesthetised – or autopsies.

Grim as that may sound, the closing pair of tracks, ‘Gravitate To Me’ and ‘Beyond Love’, are – at least in spirit – on the upbeat side. The first is eight minutes worth of flinging heavy-duty woo, which a lass might find irresistible not in the way a bouquet of roses is irresistible; rather, in the way a cyclone is irresistible.

…we are kindred spirits, born to become earthly lovers

…

I AM THE LIGHTHOUSE. I AM THE SEA.

I AM YOUR DESTINY. GRAVITATE TO ME,

In case that doesn’t clinch it, he winds up repeatedly keening, "I KNOW YOU! from a previous incarnation." By this time, Marr’s trademark shuddering guitar has taken to circling the beat with a measured, sharp-edged funk riff and the entire business has gathered a torpid but terrifying momentum that can only end with it, and its protagonist, rolling unstoppably atop its object of desire. It’s like being courted by a Panzer division. Come hither, or else.

It is, you may have gathered, a quite extraordinary piece of music.

After which, the closing ‘Beyond Love’ does what it would not do under any other circumstances. It comes as light relief. Among other things.

Our bodies stand naked as the day they were born,

And tremble like animals before a coming storm.

…

The force of life is rushing through our veins.

In & out like the tide. It comes in waves.

The drops of semen & the clots of blood.

Which may, one day, become like us.

Matt Johnson, silver-tongued devil.

Beyond the grasp of lust.

Beyond the need for trust.

Beyond the gaze of the sick & the lame.

Beyond the stench of human pain.

Has anybody since DH Lawrence invested the sexual act with such portent, such moment? And Lawrence didn’t have a band to emphasise the point with a steady, ringing backing track – which, improbably, if you stripped away the histrionic vocals, wouldn’t be miles away from what Lloyd Cole’s Commotions produced for ‘Forest Fire’.

You’d be forgiven for wondering what kind of woman would respond positively to such entreaties. But that would be to miss the point, just as it would be to say that those Expressionist pictures didn’t look like actual people or streets or buildings. Naturalism was not Matt Johnson’s business. The expression of a burning blue soul was his business. There is no 1980s The The album on which he did not do so magnificently; there is no 1980s The The album on which he did it more intensely, or intently, than Mind Bomb. He set out, explicitly, to blow the listener’s mind. Perhaps what he effected was more of a scorched earth campaign. When it’s over and you find yourself staring at the smoking rubble, your principal emotions are liable to be shock and awe.

And perhaps, after all, you might afford yourself a laugh. You’d be entitled to.