The 1970s. England, like everywhere else, is pulling in different directions. There are three-day weeks, strikes and power cuts. In February 1974, prime minister Ted Heath urges the public to “Switch Off Something” – presumably not the TV set his bulletin is being broadcast on, but anything else that drains the country’s scant resources. The Yom Kippur War of October 1973 prompts an oil crisis that chancellor Anthony Barber says will inaugurate a return to second-world-war-style austerity and ration books. Inflation sends the cost of fuel and food through the roof. There is escalating violence, on football terraces and on the streets, and IRA bombings in mainland Britain every few months. In June 1974, Kevin Gately, a young student protesting against the National Front in Red Lion Square, is the first person to die in a demonstration on English soil since 1919.

Images of destruction and armageddon proliferate on cinema screens. A couple of years ago, there was A Clockwork Orange and The Omega Man, the former withdrawn by director Stanley Kubrick because of its all-too-real impact. Disaster movies – The Poseidon Adventure, Earthquake, The Towering Inferno – are a hit. Horror movies are enjoying a renaissance that will continue throughout the 70s, a golden age that stretches from 1968’s Night Of The Living Dead to Kubrick’s The Shining in 1980. Hollywood entertainment reflects America’s doomsday complex – riven by social unrest, reeling from Vietnam. In 1973, the World Trade Center’s twin towers soar into the sky. Down on the street, New York City’s crime rate increases. Later in the decade there will be blackouts and rats crawling across uncollected garbage. It could be Hunger City. On the bookshelf, speculative fiction carries bleak urban messages too – Thomas M Disch’s 334 in 1972, JG Ballard’s High Rise in 1975.

And yet, things keep swinging. The latest party is disco, where gay, black and Latin cultures meet. In Britain, the custodians of chastity, the Nationwide Festival of Light’s Malcolm Muggeridge and Mary Whitehouse, try to stem the tide of sex. Pornography flows in from the continent, Brando’s Last Tango In Paris challenges the censors and tawdry British sex comedies challenge Hollywood’s reign at the box office. Flying in the face of austerity is luxurious profligacy, due in large part to the credit card. English people travel more than ever, developing tastes for wine and foreign food. Flamingos frolic on the rooftop gardens of Kensington High Street’s Biba, Barbara Hulanicki’s boutique for glam rockers and their teen audience.

Heath has moved a grand piano into Number 10. He is a cold man from whom passionate music pours forth, like self-confessed ice-man rock star David Bowie. Tinkling ivories signalled Ziggy Stardust’s post-Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide descent into real decadence, courtesy of scientologist Mike Garson, on ten postcards back from America called Aladdin Sane. On 3 July 1973, at Hammersmith Odeon, Bowie retires Ziggy. The singer has become the embodiment of the decade’s wild contradictions; questing, cosmopolitan, a purveyor of liberated sexual attitudes with a bleak, apocalyptic mindset.

By January 1974, Piccadilly’s lights are sometimes turned off due to shortages. Close by at the Cafe Royal, the glitterati, Hollywood A-listers, various members of the 1960s rock super-league, peers and key influences, toast Ziggy at a ‘Last Supper’. Nobody is more alive to the ironies and paradoxes of the age they are living in than David Bowie. He conducts the lightning flashes of a broken world into his new music, music cobbled together from pieces, salvaged from abortive musicals, put together with cut-up lyrics and scavenged from other sources. The result will be a hybrid as alluring and grotesque as the half-man/half-canine that crawls across its sleeve. 1974 will be the year of the Diamond Dog.

Ziggy had to die. And the Spiders had to explode across the stars like the mad ones in Kerouac’s On The Road. At his inception, Ziggy was a character doomed to self-destruct in a world that was five years from ending. But he was also the conduit through which David Bowie had become a star, so he kept him around for a while. Then he got odder. There was a nagging fear that the mask wouldn’t come off, like a modern fable.

By 1973, Pierre La Roche’s make-up was sinking into the singer’s face. The similarly kabuki-inspired Kansai Yamamoto costumes clung to him under the lights as Bowie performed night after night on tours across the world. Freddie Burretti’s original jumpsuits were torn and frayed. And the David Bowie squeezing himself into the art deco-inspired attire was a dramatically different man to the swishy Jean Seberg-like androgyne who had winked at Michael Watts for Melody Maker in January 1972 – the same month he went on stage as Ziggy for the first time.

Bowie was the reigning recording artist of 1973. All his albums from Space Oddity to Pin Ups went Top 40, and his singles sailed into the upper echelons of the chart (‘Jean Genie’, ‘Drive-In Saturday’, ‘Life On Mars?’ and ‘Sorrow’ were all Top 3). He had given others a helping hand (Mott The Hoople, Lou Reed, The Stooges).

After Ziggy bowed out, Bowie’s already hyperactive imagination and work rate went into overdrive. He took the remaining Spiders (Woodmansey was replaced by Aynsley Dunbar) and producer Ken Scott to the Château D’Hérouville near Paris to run through a selection of his favourite sides from 1964-67 – effectively the British rock trajectory from beat boom to psychedelia. He continued to act as a svengali of sorts (Lulu, The Astronettes), and he made various contributions to Ronson’s 1974 debut, Slaughter On 10th Avenue. There were countless film projects discussed, with Pin Ups co-star Twiggy, with 1980 Floor Show co-star Amanda Lear. He was a man in demand (Adam Faith wanted him for session work, Steeleye Span got him, Lindsay Kemp hoped he would play the lead in Oscar Wilde’s Salome). By 1973 Bob Ezrin had asked Bowie to contribute to Lou Reed’s Transformer follow-up Berlin. He never did, but Diamond Dogs echoes that song-cycle’s orchestrated, conceptual gloom.

Post-Sgt Pepper rock loved a big idea, and Bowie had lots of them. There were various musicals mooted that never materialised. There was a one-act play called Tragic Moments. There was the Ziggy musical (he just wouldn’t let go). In November 1973, Bowie retroactively crowbarred a new narrative into the saga, involving ‘black-hole jumpers’ who use pieces from Ziggy to take shape; one of them was called Queenie the Infinite Fox. Playwright Tony Ingrassia was brought from New York to work on it, but the collaboration yielded no results.

Earlier that year, crossing eastern Europe on the Trans-Siberian railway with Astronette Geoff MacCormack and Mainman employee Leee Black Childers, Bowie witnessed societies ravaged by totalitarianism. He wove what he’d seen, as he did with so many painful things, into a theatrical conceit: a stage adaptation of Orwell’s 1984. (‘1984’ had also been the title of a Spirit song from 1969, a mirror to a contemporary America perilously divided over Vietnam. Radio stations were warned of its subversive content and it sank without trace, like one of Big Brother’s hapless victims.)

From ‘We Are Hungry Men’ on his Deram debut (“Who will buy a drink for me, your messiah?”) to ‘Saviour Machine’’s deranged computer, from Nietzschean supermen to Himmler references on ‘Quicksand’, dystopia and the tyranny of power gone mad had long been fertile terrain for Bowie. At 1984’s heart was Winston and Julia’s doomed romance, stock-in-trade for Bowie since 1966’s ‘And I Say To Myself’. And Bowie, part Tibetan Buddhist-literate seer, part pop-plagiarist charlatan, knew all about Winston’s dilemma, his deep awareness of truth and carefully constructed lies. But Sonia Brownell, Orwell’s widow, was horrified by the proposal and withheld the rights. The project lingered in Bowie’s mind; as late as November 1973 he talked about a lavish television presentation of it.

If 1984 represented a side of the real world Bowie had seen on his Trans-Siberian journey, he had also immersed himself in its decadent antithesis. And so had his audience. On the Ziggy tours of 1972-73, American excesses gave Aladdin Sane its palpable sleaziness. Bowie had looked into crowds across the world that bordered on hysteria. In Britain, there was structural damage done to several auditoria, and usually sedate Japanese audiences were whipped into a frenzy (Angie Bowie narrowly escaped being arrested for inciting a near riot). Bowie marvelled that English fans had copulated in the crowd. Conflate this maelstrom with Orwell and eastern Europe and you have the two halves of Diamond Dogs’ whole: one side a sequence of songs from a city in decadent disarray; the other a slide into totalitarianism.

Bowie had relocated from a Haddon Hall that was increasingly besieged by fans to the more central 89 Oakley Street, a four-storey pleasure palace, with Burretti ensconced in the basement as his on-call tailor, a sunken living room, green-and-white eyeball chairs and countless hi-tech gadgets. Oakley Street was also close enough for Bowie to keep an eye on Mick Jagger, who was a stone’s throw away on Cheyne Walk. Bowie’s fascination with The Rolling Stones was ever-deepening. Aladdin Sane contained a stab at Exile-style insouciance (RCA had originally wanted Ken Scott to remix ‘Watch That Man’ with less upfront guitars), a reference to Jagger on ‘Drive-In Saturday’ and an impudent cover of the Stones’ ‘Let’s Spend The Night Together’ (out-camping the original, strewn with strobe-light synths). Jagger was now in Bowie’s orbit – a friend, rival, peer and, if Angie Bowie is to be believed, a sometime bed companion.

But most of all he was raw material. During this period Bowie studied Jagger closely, and Diamond Dogs was largely recorded in the Stones’ favoured facility, Barnes’ Olympic Studio 2, with their engineer Keith Harwood. It would be full of shameless quotes from the Stones canon. For tax reasons, some of Dogs was recorded at Studio L Ludolf, near Hilversum in Holland. But the Stones recorded there too; he just couldn’t let Jagger out of his sight.

Bowie also befriended Ronnie Wood. They recorded a throaty, faithful version of ‘Growin’ Up’, a song by Bruce Springsteen.

Springsteen seemed like Bowie’s polar opposite, but in his own way the up-and-coming singer-songwriter synthesised influences as cannily as Bowie: the Dylanesque poetics, the Brando/Dean leather jacket and brooding masculinity, the vintage rock & roll. By 1975’s Born To Run, this was wrapped up in Spectoresque walls of sound and West Side Story flourishes. Songs like ‘Jungleland’, with their urban imagery and magic rats, inhabit the same place as Diamond Dogs’ Hunger City, with hard-boiled sax and mean streets. According to a MOJO interview with Andy Morris, assistant engineer on Diamond Dogs, Bowie played Springsteen’s ‘Spirit In The Night’ constantly during album sessions. Listen to the syncopated drums and piano on ‘Alternative Candidate’ and you can hear it, stirred with Brel (the eventual ‘Candidate’ turned Springsteen’s late-night shuffle into a nocturnal nervous disorder).

Bowie’s fixation with the Stones roughly coincides with their artistic decline. Goats Head Soup may be fine, but by 1973 the band had broken the classic seven-album sequence that ran from 1968’s Beggars Banquet to 1972’s Exile On Main St. Bowie’s ‘assimilation’ of the band took them to more inventive areas. Aladdin Sane wore its Stones influences overtly but it also pushed Bowie further into the avant garde: Mike Garson’s Chopin-meets-Dali piano; the martian doo-wop Roxy-prompted ‘Drive-In Saturday’. (Bowie had wanted Mainman’s electro-jazz pioneer Annette Peacock to play synth on Aladdin, and when she declined he got Peacock’s band member Garson instead.) Diamond Dogs subsumed the Stones and Springsteen into dystopia, funk and increasingly electronic musical landscapes.

Bowie’s interest in electronics predated his studying of support act Roxy Music. Electro-mechanical mellotrons had given ‘Space Oddity’ its disembodied ambience, and the song also featured the stylophone (which Bowie advertised in the wake of its success). The stylophone made a reappearance on The Man Who Sold The World, along with Ralph Mace’s unwieldy Moog synthesiser (still somewhat rare in Britain in 1970). During the Hunky Dory/Ziggy period, just an ARP or mellotron appears here and there, although Ziggy made his stage entrance to Wendy Carlos’s Moog makeover of Beethoven’s ‘Ode To Joy’ from the Clockwork Orange soundtrack. By Aladdin Sane, synths were creeping back in – no doubt Eno’s VCS3 manipulations were catalytic. On Pin Ups a Moog rumble tears through Billy Boy Arnold’s ‘I Wish You Would’ like future electro-missiles dropping on vintage R&B. Released the same year as Kraftwerk’s Autobahn, Diamond Dogs would rely heavily on Moogs and mellotrons to paint its aural pictures, making it a harbinger of Bowie’s full-on plunge into electronics with Eno later in the decade.

Bowie was now closer to Kensington High Street’s Sombrero, aka Yours Or Mine, the gay discotheque with its perspex underlit multicolour dancefloor. He and Angie had frequented the venue as Ziggy was taking shape, and now it was a portal to the burgeoning American disco scene, playing records that were stretching R&B with extended danceable breaks (The Temptations’ ‘Law Of The Land’, Eddie Kendricks’ ‘Girl You Need A Change of Mind’), sweetening it with strings (Barry White) and smoothing its rough edges with opulent production precision (Gamble and Huff’s Philadelphia sound). Throughout the 1960s soul music expanded its sonic palette – even Berry Gordy’s Motown was embracing psychedelia with Norman Whitfield’s envelope-pushing productions for The Temptations (‘Ball Of Confusion’). The Supremes dabbled with space-pop intros on ‘Reflections’; southern soul auteurs like Swamp Dogg upholstered their recordings in novel musical settings. It also got conceptual. One Swamp Dogg production, Doris Duke’s 1969 I’m A Loser, predicted the ‘other woman’ song cycle, popular in the 1970s with other masterpieces like Millie Jackson’s 1974 proto-rap Caught Up.

Soul was having a dialogue of sorts with rock, thanks to post-Beatles studio innovations and a vaguely conceptual flow from song to song. Landmark albums emerged from Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder, whose productivity rivalled Bowie’s and whose pioneering use of electronics on 1972’s Music Of My Mind emerged the same year as Roxy’s eponymous debut. Curtis Mayfield’s Superfly, Bobby Womack’s Across 110th Street and Isaac Hayes’ Shaft, at once cinematic and disco-ready with sweeping strings and crisp rhythm tracks, soundtracked blaxploitation movies and filled dancefloors.

R&B was galvanic to the young Bowie, as it was with most of his generation (he covered Bobby Bland’s ‘I Pity The Fool’ in 1965 with The Manish Boys). He was alert to its developments, some of which were mirroring his own – a hybridised musicality, an expansive, symphonic sweep with lush textures and concepts. The Stylistics had been on heavy rotation on the Ziggy tour bus stereo; the Thunderthighs’ wail had blown through Aladdin Sane like a wind of soul-change to come.

Always sensitive to coming trends, Bowie possibly saw R&B as the way to greater American success (he was right – as Young Americans, an album both personal and shrewd, attested). And as Lester Bangs observed: “No gay bars have ‘Rebel Rebel’ on the jukebox; it’s all Barry White and the big discotheque beat.” Diamond Dogs would exhibit a growing interest in soul (‘1984’, ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll With Me’) but the sessions would yield embryonic versions of even deeper cuts (Young Americans‘ ‘Right’ and ‘Can You Hear Me?’). He wasn’t alone: Marc Bolan was inflecting T.Rex’s Zinc Alloy with soul, via Gloria Jones; Elton John was on Soul Train before Bowie, releasing ‘Philadelphia Freedom’ before Young Americans.

The endless socialising with rock royalty and the partying at the Sombrero gave the impression of total early 1970s hedonism. But, as on ‘Sweet Thing’, Bowie may have been “at the centre of things”, but he was also “scared and lonely”. From his own father Haywood Jones onwards, Bowie had always had a benign father figure guiding his music – Leslie Conn, Ralph Horton and, perhaps most of all, Kenneth Pitt. Pitt’s replacement Tony Defries had helped Bowie become a star, together they had devised the Mainman organisation’s assault on entertainment. But as 1973 went on, Bowie came increasingly aware that Mainman was an empire built on sand, bankrolled by RCA’s advances, unable to account for its profligate spending. Bowie was almost banned from using Olympic Studios until unpaid Mainman bills were settled. In tandem with this tumult, and an open marriage that was falling apart, was the singer’s escalating use of cocaine. Cocaine was then considered little more than music-biz fuel, vital for a workaholic like Bowie, but it quickly became a crutch.

Unmoored from the Spiders, Bowie seized control of his music, producing the sessions, arranging the songs. He also handled the lion’s share of the guitar parts, eager to prove his mettle without Ronson. Alan Parker helped out, beefing up ‘Rebel Rebel’, playing wah-wah on ‘1984’, and bringing bassist Herbie Flowers from Blue Mink with him. The pair had also worked on Transformer, and Bowie had used them on 1971 flop single ‘Holy Holy’ (the Spiders’ superior remake cropped on the ‘Diamond Dogs’ single B-side in 1974).

Bowie’s chosen guitar for the sessions was a Dan Armstrong plexiglass model, heavyweight and notable for its striking use of sustain. His guitar-playing has a child-like ostentation – intuitive, expressive, all ‘sonics’ rather than technical proficiency or the fluid riffage of Ronson. His playing gives the album much of its edge and character, an untutored template for all his post-Ronson guitarists: the howl of Earl Slick, the rhythm of Carlos Alomar, leftfield noiseniks Robert Fripp, Adrian Belew, Reeves Gabrels. It’s his fretwork that makes the album feel like a punk building-block – the serrated post-punk edges of Keith Levene or John McGeoch seem to be distant cousins.

If Bowie was sinking into a depression, he retained a child’s sense of wonder in the studio. He had always thought about music in three dimensions. Now, armed with abandoned musical scraps and an interest in German expressionism, his music became even more visual, abetted by Mike Garson and his evocative keys. The German cinematic style could be one of Diamond Dogs‘ deepest influences – heightened, heavily stylised, full of light and shadows, full of fractured characters. And Bowie was the auteur (Morris likened him to Orson Welles in that MOJO interview).

This directorial approach involved using the session parts like scenes to be shuffled, edited, anticipating the ‘layered’ techniques of 1980s recordings (part of Diamond Dogs‘ additional recording was done at Island Studios, which became Sarm West, the hub of Horn/ZTT’s cut-and-paste art-pop). There are also parallels between Bowie during this period and Todd Rundgren, whose electro-japes, blue-eyed soul and pocket symphonies across albums like A Wizard, A True Star and Todd both echo Dogs’ autonomy and auteurism (all paving the way for Prince’s 1980s purple patch).

For the ‘Sweet Thing’/’Candidate’ suite, Bowie told Sounds Incorporated drummer Tony Newman to play as if he was a French drummer boy witnessing his first execution during the Reign Of Terror. On the same song, he dimmed the lights for his vocal, displaying a method actor’s commitment to evoking a song’s character. And those vocals were his most potent yet, displaying an unforced swagger when the material required it (‘Rebel’, the title track), pulling and stretching at every word operatically elsewhere (‘Sweet Thing’, most of the second side). Equally expressive was his sax playing, perfectly occupying the mid-point in style and time between ‘Soul Love’’s smoky serenade in 1972 and ‘Neuköln’’s avant-wheezing in 1977.

Scott’s production on Hunky Dory and Pin Ups was mostly restrained, then he loosened his tie at the mixing desk somewhat for Aladdin. But Diamond Dogs was the first Bowie album since The Man Who Sold The World that seemed to use the studio as a musical instrument; it was a return to the Sgt Pepper-esque mood of experimentation that the 1970 recording had been approached with (and that time constraints had prevented them from fully exploring). It’s unsurprising then that Diamond Dogs’ bold sound design was where Bowie resumed his working relationship with Visconti.

By 1973 Visconti was at the end of his working relationship with Bolan. T.Rex’s run of hits was coming to an end; the sprawling (actually sporadically brilliant) Zinc Alloy And The Hidden Riders Of Tomorrow was their final work together. By January 1974, Bowie was phoning Visconti to ask him about mixing Diamond Dogs. Visconti had just installed a studio at his Hammersmith home, replete with an Eventide Digital Delay unit (a few years later the Eventide Harmonizer would give Low its signature drum sound, “fucking with the fabric of time,” as Visconti put it). Visconti did a rough mix of the Diamond Dawgs tapes (working-title spelling) for Bowie (at the wrong speed, he claims) and Bowie loved it. The next day a Conran lorry pulled up with furniture and kitchen utensils and most of the album was mixed there, at Visconti’s home studio, over glasses of claret.

In November 1973 Rolling Stone magazine’s A Craig Copetas conducted an interview with Bowie and William Burroughs, published the following February. Burroughs already had something of a rock pedigree – his books had inspired the names of both Soft Machine and Steely Dan. At Bowie’s home, they discussed pornography, love (a collective “ugh!”), and how audiences were more outrageous than rock stars.

Bowie described Burroughs’ work as “a whole wonderhouse of strange shapes and colours, tastes, feelings”, and claimed that 1971’s The Wild Boys: A Story of The Dead had inspired Ziggy. It was unlikely: Copetas had only just given him Nova Express to read, and in the interview we find that Bowie didn’t realise the Wild Boys’ chosen weapon was an 18-inch bowie knife. It didn’t matter. The man who as a teenager had proudly flashed a paperback’s title in his pocket before he’d read it now quickly incorporated the Wild Boys into Diamond Dogs – another layer of nihilism, apocalypse and the homoerotic.

Burroughs also mistakenly thought that Bowie had read TS Eliot, singling out ‘Eight Line Poem’’s resemblance to ‘The Waste Land’. (“Never read him,” replied Bowie.) Listening to Diamond Dogs, it’s hard to imagine that Bowie was still unfamiliar with Eliot; there is a striking similarity between the poet of ‘stony rubbish’ and the Diamond Dogs rock star of Stonesy remnants.

The meeting prompted a sea-change in Bowie’s songwriting methodology. Inspired by the cut-up techniques Burroughs’ partner Brion Gysin had devised as early as 1959, Bowie started composing by cutting strips of paper and putting them back together, allowing a song to be composed or triggered by the juxtapositions (he later claimed to have used this technique tentatively on some of Aladdin too).

Early Bowie songs had a clear narrative thread (the kitchen-sink realism of ‘London Boys’, the mythology of ‘Wild Eyed Boy From Freecloud’) but over time his songs became cryptic and fractured. Songs from The Man Who Sold The World onwards would lure you in with that storyteller’s grasp of scene-setting, only to leave you adrift in an ocean of riddles and enigmatic imagery (‘Life On Mars?’, ‘Bewlay Brothers’).

Cut-ups seemed to be the perfect device for a mind that was already thinking in a fragmentary way. This technique had manifold benefits; condensing Bowie’s constant ingestion of stimuli, accommodating a mind that couldn’t slow down, it could stitch together plans and ideas that were in pieces and, perhaps most useful of all, it could consign his deepest, darkest personal thoughts to the realms of the random and obscure. It’s unclear how much of Dogs actually consists of cut-ups. The title track, ‘We Are The Dead’ and ‘Sweet Thing’/’Candidate’ definitely feature cut-up lines, but elsewhere it seems to be used as more of a trigger, a signpost to new strands of thought. Nico needed heroin to slow her mind down, she once said. Bowie required a method that would harness his perpetual motion.

On a wider level, it was the perfect narrative technique for a world that seemed to have none, an anti-narrative for an atomised late 20th century. Joan Didion’s compendium of essays glancing back at the 1960s was called The White Album, conflating the decade’s rapid social change with the fractured musical landscape. Even Hollywood, the bastion of mainstream entertainment, produced a cinema of a centre that cannot hold: Vietnam-singed road movies like Easy Rider where characters never reach their destination, films made with new-wave techniques ending in European-style ambiguity. By 1975 and Dog Day Afternoon, the post-Stonewall American protagonist couldn’t even be relied on to be entirely heterosexual.

So cut-ups seemed the logical device for an illogical world. It had been a century of cuts, from Soviet montage to Godard’s jump-cuts, from Eliot and Pound’s disjointed poetics to the psychedelic era’s tape-splicing. And of course it didn’t hurt that Jagger had toyed with the strategy on Exile too.

In the 1960s, rock had hurtled forward, rapidly evolving before crashing and splintering like the decade’s social changes. As a response to psychedelia and the shattered hippy dream, some recovered in Laurel Canyon, analysing personal relationships in forensic detail, others embraced the virile certainties of heavy and progressive rock. Glam rock had retreated into style, embraced showbiz, artifice, the simple effervescence of rock & roll’s first rush. The presentation was self-conscious, heightened like a pop-art twist on a familiar theme.

But glam had its own in-built contradictions, with prog elements at it is very root (Roxy’s original guitarist was Davy O’List from The Nice, King Crimson’s Pete Sinfield produced their debut, their pre-1975 music frequently wandered into progressive territory). Bowie wrestled with concepts that mirrored the Orwellian preoccupations of post-Dark Side Floyd. Sometimes it feels like the influence flowed the other way too. Led Zeppelin’s ‘No Quarter’ could be a Roxy/Floyd wig-out. Genesis frontman Peter Gabriel shared glam’s love of a frock and theatre. In the year of the Diamond Dogs, a lamb was lying down on Broadway – bestial, urban and flamboyant, going where Aladdin had gone before, propelled by Tony Banks’ frantic Garson-like keys. (The Genesis double was occasionally filtered through the manipulations of Bowie’s future foil, Brian Eno, who was credited for his “enossification”.)

Glam was a revolt against rock’s pomposity and excesses, and existential doubt nagged underneath the work of its most savvy progenitors. Mott The Hoople’s Dudes carried the news of a post-Beatles youth movement, but Bowie had decided that, like in ‘Five Years’, the bulletin was the world’s end. Little wonder then that the glam youth were, to quote Eno’s post-Roxy ‘Cindy Tells Me’, “confused by their new freedoms”, playing dress-up and taking advantage of post-1960s sexual liberation in a world that seemed to be hurtling towards destruction. Black holes threatened to swallow Roxy on their early work, black-hole jumpers were going to eat Ziggy; these were the perils of glamour in an age of glum forecasts, the instability of decadence in a century of violence (something Ferry and Bowie, both enamoured with interwar culture, were well aware of). And at the other end of the spectrum, Mott, The Sweet and Slade simply weren’t going to slap on the make-up forever.

Glam entered a sort of ‘high’, a decadent phase before fading in the mid 1970s. Throughout 1973-74 its satin attire would fray and tear. It was getting odder (Sparks) and grander (Cockney Rebel’s rococo pop opera ‘Sebastian’, T.Rex’s MGM-lavish ‘Whatever Happened To The Teenage Dream?’). Its thuggish edge got sharper, Mott’s dudes got into ‘Violence’, were dressed to kill on ‘Crash Street Kidds’. Skinhead novelist Richard Allen even wrote the Glam novel, with Aladdin Sane’s lightning bolt slashed across its cover. John Cale’s foray into glitterbeat on the otherwise elegant Paris 1919 was a manic, psychotic Macbeth. If glam had used rock as the “Pierrot medium”, to quote Bowie, it was now becoming something of a monster.

And it became less popular. T.Rex’s astonishing sequence of chart-toppers gave way to bloated dumper-bound brilliance. Even glam’s bubblegum variants got sad, there was the gravitas of The Sweet’s ‘The Six Teens’, casting its eye back to the revolution rock of 1968 on an album called Desolation Boulevard (they split from the Chinn-Chapman hit-making machine shortly after). And the Slade In Flame film of 1975 features the Birmingham good-time glam-rockers getting reflective (on the lovely ‘How Does it Feel’), as jaded by music-biz machinery as the Floyd of ‘Have A Cigar’.

A few weeks before Ziggy retired, Eno was ousted from Roxy Music; the foil and leopard print and boas followed soon after. Both Stranded and Country Life wrestle with art-glam, before Roxy move closer to black America on Siren. By 1974, Bryan Ferry posed on his solo ‘Another Time, Another Place’ oozing Gatsby cool. Lou Reed quickly ditched glam, refuting it with buzzkill rock opera Berlin. The New York Dolls wouldn’t make another album that century, after 1974’s Too Much Too Soon.

Tarting up Bo Diddley in satin and tat wasn’t going to work anymore. In 1975, the year Roxy and Bowie permanently left it behind, Slade In Flame and Mott’s Ronno-assisted ‘Saturday Kids’ (“We didn’t much like dressing up anymore”) both waved goodbye to glam. Perhaps Queen’s A Night At The Opera was the final bombastic bang of the gong.

You could hear Dr Feelgood’s Down By The Jetty, back-to-basics R&B, coming out in 1975 on one-channel mono; the year before there was Patti Smith’s ‘Hey Joe’/’Piss Factory’ single. Both signalled a slate wiped clean to welcome in punk. Even louder perhaps were the proto-boyband confections of Bay City Rollers and Showaddywaddy; glam showbiz divested of all artifice and irony. Amid this fallout, somehow soaking it all up like a sponge, crawling across the slimy thoroughfare came the Diamond Dogs.

It starts with an otherworldly squall, Lou Reed’s Berlin title track reimagined by Joe Meek’s ‘I Hear A New World’. ‘Future Legend’ raises the curtain on Hunger City, a vision of urban decay where “red mutant eyes gaze down” while “fleas the size of rats suck on rats the size of cats” and “ten thousand peoploids split into small tribes”. The almost cannabalistic imagery stretches back to ‘We Are Hungry Men’ (“We’re here to eat you!”) and the sonic mise-en-scene recalls the Deram debut too, chiefly ‘Please Mr Gravedigger’’s BBC Radiophonic Workshop-like invention. A brief prelude, ‘Future Legend’ compresses Bowie past and present with the future shock of the icy synths, offering a glimmer of his late-1970s horizons. Only here the effect is a little proggy, a theatrical nod to fellow Bromley boy HG Wells perhaps, taking Orson Welles’ radio-play scaremongering one gaudy step further, four years before Richard Burton spooked young listeners on Jeff Wayne’s musical version of The War Of The Worlds (listen to Peter Gabriel’s 1977 ‘Moribund The Burgermeister’, another swamp of sonic weirdness).

The apocalypse builds, from the mutant groans on Love Me Avenue to Tin Pan Alley as Rodgers & Hart’s ‘Bewitched, Bothered And Bewildered’ makes a brief, surreal cameo on phased guitar (echoing Ronson’s sublime take on Rodgers’ ballet-within-a-musical Slaughter On Tenth Avenue, also a Bowie suggestion). The denizens of Hunger City scavenge and loot in the face of collapse, “ripping and re-wrapping mink and shiny silver fox.” Oft-lampooned for what Peter Doggett calls “sci-fi juvenilia”, it’s hard to imagine Bowie was being entirely serious in ‘Future Legend’: “mink and shiny silver fox” are reduced to “legwarmers” with a wink of comic timing.

Wipe the patina of schlocky imagery from ‘Future Legend’ and you have a glimpse of the generation that would shape punk. Bowie was surveying his audience’s resourceful DIY tailoring to mimic Ziggy, reconstructing clothing, “ripping and re-wrapping” found elements two years before Jon Savage saw the crowd doing the same at a Runaways concert in the Camden Roundhouse. The next song has “mannequins with kill appeal” who could be Mott’s droog dudes, McLaren and Westwood’s Kings Road oiks, even the Blitz kids with their statuesque hauteur. And as for looting – two west London delinquents had stolen the Spiders’ equipment at the final Odeon show; they were Steve Jones and Paul Cook, soon to be the Sex Pistols’ rhythm section.

What follows is an act of creative theft as larcenous as the scavengers of Hunger City. Even the introductory crowd on Diamond Dogs’ title track is cribbed (from The Faces’ live album Coast To Coast), Stones motifs are overlaid (the cowbell hip-swivelling of ‘Honky Tonk Women’, ‘It’s Only Rock ’n Roll’ cheekily incorporated into live versions),and by the climax, it ‘quotes’ Bobby Keys’ sax riff on ‘Brown Sugar’. Even Ziggy building-block Vince Taylor helps out with lyrical props (the broken elevator is from Taylor’s ‘Twenty Flight Rock’). These found sounds and details are paraded in the wonderhouse of Bowie’s imagination, lyrically woven into a surreal caper, equal parts Marvel comic strip and Grand Guignol.

Images come thick and fast; it’s as tumescent as the ten-inch stump that protrudes from the first verse’s rollicking grotesquerie. An amputee dressed as a vicar gets pulled out of an oxygen tent and crawls down the street in search of a party, eliciting a comparison with the circus hands in Tod Browning’s 1932 film Freaks.

And the sideshow rolls on. By the second verse, “Halloween Jack is a real cool cat who lives on top of Manhattan Chase”, sliding down a rope like Tarzan through an urban jungle, or Joe The Lion slithering down the greasy pipe, like the loping beat on the Stones’ ‘Monkey Man’. Any hope that Halloween Jack was Bowie’s latest alter ego was in vain – he amounted to an illusory presence, like so many of the inhabitants of Hunger City, gone in a flash.

Sonically, what should be a Stones xerox comes out as a skewed rock & roll oddity, like 1971’s ‘Stranger In Blue Suede Shoes’ by Kevin Ayers, where an insouciant shuffle is midway turned on its head with a Garson-like careen down the ivories. Bowie’s scratchy rhythm guitar sounds like a kid let loose on the adult machinery of Keith Richards’ guitar, truly the birthplace of punk’s enfant terrible primitivism. Diamond Dogs roughs up its references, rock past as found sound, musique concrète, a flash of pop future in its proto-hip-hop sampling, an assemblage from stolen pieces (see also Beck, who covered it for the Moulin Rouge! soundtrack in 2001).

Overloaded with overdubs, stressed with stimuli, like an overused reel-to-reel, Diamond Dogs has a submerged feeling, heightened by that gargling effect lacquered onto the vocals with the Keypex, a primitive sampling device from Visconti’s box of tricks (three years after Sly Stone’s overdubbing muddied There’s A Riot Goin’ On, five years before Lindsey Buckingham’s lo-fi rumble was let loose on Fleetwood Mac’s Tusk). It could be the first hauntological rock & roll song, its robotic click-track rim-shot percussion calling time on Bowie’s rock phase, just as the Stones were settling into the complacency of ‘only rock & roll’.

Diamond Dogs piles up, ending in textural carnage: dog noises; synthetic effects; saxes; scratchy guitars; keys; Phil Spector-meets-The Beatles’ climax on ‘Good Morning, Good Morning’. It is the great lost single of the mid 1970s, left languishing outside the Top 20, but its doomsday bonhomie is the spirit of the age, shimmying in the face of encroaching catastrophe. Like Depression-era entertainment, it faces the music and dances.

Lester Bangs mocked Bowie, and Bowie mocked Alice Cooper, but Bangs’ Rolling Stone review of Cooper’s 1971 album Killer makes it sound like a dry-run for Dogs: “Alice is creating absurd and outrageous collages of idiomatic borrowings combined with a distinctly teen-age sense of the morbid.” Glance at Dogs’ sicko-sleaze Guy Peellaert sleeve and listen to Killer’s own Stones/Rogers & Hammerstein borrowings, sound effects, Clockwork Orange synths and the two look like kindred spirits, albeit briefly.

Taken together, ‘Future Legend’ and ‘Diamond Dogs’ rummage through a rubble that is at once rotting and bejewelled with “family badge of sapphire and cracked emerald’. Maybe all the childlike marvelling at the debris reveals the real root of Hunger City’s inspiration: the Dr Barnado’s worker, Bowie’s dad Haywood Jones, regaling his son with stories of gangs of children living on the rooftops of Dickensian London. When Bowie drew storyboards for the planned Diamond Dogs film, the characters looked like Huck Finn and Oliver Twist.

The next three selections are best taken as one piece of music. Backwards tapes (a mellotron?) introduce the ‘Sweet Thing’/’Candidate’ triptych, a startlingly visual tremor, like a Edward Hopper painting coming to life, a vast Fritz Lang cityscape rising to obliterate the skyline, the start of Gershwin’s ‘Rhapsody In Blue’ played in slo-mo. An exquisitely layered, emphatically urban torch song begins. Bowie croons in basso profundo before gliding into a higher register, wringing every drop of emotion from each word. It’s his most expressive singing yet, a well of loneliness as profound as that of the cinemagoing girl in ‘Life On Mars?’ or the London Boy. “Scared and lonely”, the figure rushes to the “centre of things” but here he only finds “love in a doorway”, a cold caress casually given by the multitracked voices, strangers rushing by offering only temporary relief. They are phantoms, like those that dwell in Eliot’s Unreal City: “I had not thought death had undone so many.”

A glimmer of hope arises in the second verse: the love of an older partner (a kept boy serenading his sugar daddy?). Garson’s keys tinkle approvingly like city lights in sharp focus. But it proves fleeting. “If this trade is a curse, then I’ll bless you and turn to the crossroads and hamburgers” – a cut-up curio or a hustler returning to the street?

The music conjures details from a movie screen – saxes ooze, smoke rises. The mood of elegant refinement is evocative of the vintage romances of Tin Pan Alley, and Bowie comes on like a gothic Johnny Ray, but here the gutter is in full view (that scuzzy guitar runs below the cascading wall of sound). A grand, trashy solo is unleashed, like the glitter-strewn casualty Bolan offered on ‘Teenage Dream’.

If this was Hunger City, then it was at one with Eliot’s Unreal City, a place where lovers depart unnoticed in hotel rooms. Perhaps the triptych is best seen through the prism of ‘The Waste Land’, where a series of voices offer a panoramic survey of a disenchanted world. (Eliot’s poetics were given pop appeal on the Pet Shop Boys’ ‘West End Girls’ and Radiohead’s ‘Paranoid Android’ owed much to him.)

‘The Waste Land’ might not be directly referenced but it seems at one with Bowie’s fractured cityscape. Then again, this could be a familiar 1970s milieu , the pick-up station where you hope for warmth and beauty and settle for “less than fascination” in Joni Mitchell’s Down To You on 1974’s Court And Spark, another record about being scared and lonely at the centre of things. Mitchell’s 1974-75 work is rarely compared with Bowie’s but there are parallels: portmanteau structures; filmic flourishes; a jazzy audacity borne of a creativity that followed its own path through the 1970s. And on her The Hissing of Summer Lawns’ title track, there is “a diamond dog carrying a cup and cane”.

Then the scene shifts to ‘Candidate’. The lights dim in Olympic Studios as Bowie prepares for another character and that martial Reign of Terror drumming heralds dread. A lone sax is blown through the mix, jazzy, sonic shorthand for the urban, the nocturnal, the sinister. This is the city of 1970s film noir, now reminiscent of Taxi Driver, which was still two years away, with Herrmann’s final score and its Guy Peellaert posters. Bowie’s sax could be Harry Caul practising in Coppola’s The Conversation.

Bowie begins singing with shaky faux-assurance, the “superficial calm” he observed in LA in the back of a limo during Alan Yentob’s Cracked Actor documentary, eyes nervously flicking from side to side. He could be a hustler straight out of John Rechy’s City of Night, scanning the room for johns, well aware that the ground could open up into an abyss of existential dread at any point. A jagged guitar lurks in the shadows before it starts duplicating Bowie’s vocal, trailing him like a guilty conscience.

“We’ll pretend we’re walking home because your future’s at stake,” he says, a time-bomb ticking like the two boys in the corridor at the start of Patti Smith’s ‘Land’ (a Wild Boys-inspired fight scene). Who was the candidate? A prostitute? A politician? A composite of lost souls in a 20th-century city? A nameless venom hangs heavy, like the one that moves freely through Winston during 1984’s two minutes of hate.

As the mood intensifies the images rush by, saturated in scandal, rumours and lies. The paranoia could be due to an illicit tryst with a public figure or just one that runs rife in Watergate’s era of surveillance. Something is scrawled on the wall: “I smell the blood of les tricoteuses” – the women who knitted while the guillotine dropped during the Reign of Terror, with their frivolity in the face of barbarism, desensitised to human suffering. The music surges as the images flood out; it’s a three-chord thrash and a cut-up open wound, spewed out like multitracked vomit.

The relentless, honking chug of Roxy’s ‘Remake/Remodel’ is now no longer the sound of a rock & roll band but the merciless passing of time. The sun drips blood, love is squandered in various locations, the vernacular is street-level, gay. The line “when it’s good it’s really good, when it’s bad I go to pieces” sums up the party in William Friedkin’s The Boys In The Band, where chat descends into bitchiness then into despair. The graffiti that smells blood is given resonance by a mention of Charles Manson. (Manson indirectly appeared in ‘Revolution Blues’ by Neil Young that year, killing Laurel Canyon’s stars in their cars, hoping that “you get the connection, because I can’t take the rejection”, sounding a lot like Bowie’s Candidate.)

In 1970s Hollywood, rot surfaces on the sunniest veneers. There’s the evil that reveals itself in Polanski’s Chinatown under pristine cinematography; in Schlesinger’s Day Of the Locust Karen Black admired the swing of her gown in the mirror while the film cut to the flying feathers of a cockfight. Maybe Tinseltown was haunted by the Manson murders, still in the air when Bowie got there, he claimed in 1993. Diamond Dogs is Bowie’s last London album, but he could have been singing it from America already, a place of boundless possibility, where the essential soul was, in DH Lawrence’s words, “isolate, stoic, and a killer”.

The rush of negativity propels itself to an exit, climaxing with “We’ll buy some drugs and watch a band, then jump in a river holding hands.” In ten years the sweet certainty of The Beatles’ ‘I Want To Hold Your Hand’ has become reckless oblivion, maybe even a suicide pact, the good times of the last decade sapped of their innocence, replaced with romantic-nihilism. Lost in the maelstrom are quotes from Perry Como’s ‘On The Street Where You Live’ and (later) the Beatles’ ‘Let It Be’, now just a heap of broken images in an uncertain world, empty signs of yesteryear’s romantic warmth and the 1960s’ peace-dream (see Bowie’s slogan rant at the end of ‘Cygnet Committee’). That year John Cale sang ‘Fear Is A Man’s Best Friend’ – more alienated anti-narrative, more piano-led prettiness unravelling into psychosis.

From this debris, ‘Sweet Thing’ returns, a sax gasps for air, the refrain now sounding like Eliot’s Sweet Thames, something once beautiful, now polluted. And then Bowie delivers the killer blow: “Is it nice in your snowstorm? Freezing your brain, do you think that your face looks the same?”

A prophetic jump-cut to the horrors on Doheny Drive that awaited him? Ruthless autobiography safely shuffled in Burroughsian cut-up? It’s a devastating moment, with cold-eyed clarity and warm-hearted humanity emphasised by the phased guitar line’s tugging counterpoint. Amid the tumbling crescendo of the music, the voice could be, like Winston’s in 1984, that of “a lonely ghost uttering a truth no one would ever hear” (or at least not yet). Like the two souls passing on the stairs in The Man Who Sold The World, old friends or selves momentarily became reacquainted. It could be David Jones briefly encountering the constructed Bowie, issuing shivering dismay before evaporating again. In 1976, interviewed by Jean Rook for The Daily Express, Bowie said of David Jones: “I liked him. I still like him, if I could only get in touch with him.”

Bowie seemed aware here that cocaine was more than fuel. Eliot’s “forgetful snow” that hid the decay of winter is now cocaine blanketing the entertainment industry, ravaging the septum and numbing the soul (the “perfect drug for a hitman but not so good for a musician,” Joni Mitchell once said). The same year Lou Reed asked, “Isn’t it nice, when your heart is made out of ice?” on ‘Ride Sally Ride’. The orchestral indignation on ‘Sweet Thing Reprise’ laments the waste, the toil, of addiction. It’s as sadly majestic as John Cale’s similarly frosty ‘Antarctica Starts Here’ (with “the paranoid great movie queen”) or Warren Zevon’s raging on ‘The French Inhaler’ when the bar’s closing lights come up (“Your face looked like something Death brought with him in his suitcase… Another pretty face devastated”).

And 1974 was the year Marc Bolan’s cherub face got bloated with excess and self-delusion. The year bald man with wild, staring eyes recorded his last session, standing where the pretty, puckish Syd Barrett used to. The same year Nilsson’s heavenly voice fell to earth on a beach in California, evidenced by the heartbreakingly hoarse performance on Pussy Cats, made with the man who was lying on the sand next to him, Bowie’s future friend John Lennon. Nick Drake died in 1974, and the previous year little-known genius Judee Sill recorded her last released album for Asylum; the seer was no longer welcome in the brutal and chaotic 1970s. In 1974 the acetate of Gene Clark’s visionary No Other ended up in David Geffen’s bin; Cosmic American wisdom was supplanted by the cocaine cowboys (not that Clark himself abstained). In 1974 Grievous Angel was Gram Parson’s posthumous release – he had overdosed the year before in the Mojave Desert. And in 1974, Crowley enthusiast Graham Bond killed himself. Nobody’s face looked the same.

And ‘Sweet Thing Reprise’ ends in destruction. First the voice soars to its highest register, as exultant as a sweeping crane over a Gene Kelly street scene. Romance returns once more. There’s one last pirouette from the piano before a mechanical grind kicks in, wiping away all vestige of living grace. The sound conveys some unspeakable horror. What started out as a widescreen love song ends in the violence of a whole century: the tinkling of champagne glasses before the Titanic hits the iceberg; Nazi thugs calling time on Weimar decadence; the Manson family arriving at Cielo Drive.

And yet the jarring shifts also signify the creative flux of modernity. Those violent incisions are the slice of Buñuel’s eyeball, the ‘Big Shave’ in Scorsese’s short film, wildly creative responses to war-torn worlds. Everything is locked in a tension, the opposing forces of creativity and destruction, love and hate.

Or perhaps it dramatised the changing of the musical guard to come. During the Pin Ups sessions Bowie played journalist Martin Hayman a piece intended for Tragic Moments, most likely the unreleased ‘Zion’/’A Lad In Vein’. Snatches of its mellotron woodwind/Garson piano-skating would surface on ‘Sweet Thing Reprise’. Ronson slices through the soft-focus with proto-punk riffage, predictive of the Pistols’ airless assault (see also Roxy’s ‘Editions Of You’). Bowie has no words, he just la-las, revelling in the face of unrest like Waugh’s bright young things in Vile Bodies, or perhaps like the Biba kids sipping cocktails and watching the flamingos in 1970s Britain.

‘Sweet Thing’/’Candidate’’s mutant montage is as great as anything Bowie ever recorded. It’s a razor-sharp enigma: savage, sorrowful, blessed with something that approaches the sublime. Three years later the ad said it all: “There’s old wave, new wave and there’s David Bowie.” ‘Sweet Thing’/’Candidate’ was prog protean and punk prickly (not that the class of ’76 ever sounded quite this subversive); it was post-punk before the main event. Through the rubble of cut-ups shines his creepy hypersensitivity to cultural context, soaking up the world he was living in like that fly in his milk in the limo in Cracked Actor. ‘Sweet Thing’/’Candidate’ is excessive, operatic, constantly building and falling, in hot pursuit of a centre when there is no centre left.

After such century-shaking convulsions, ‘Rebel Rebel’ leaps forth, offering unfussy relief. Off the cuff, a tad scruffy, eternally charming, the last of Bowie’s glam-rock singles. Aynsley Dunbar, the man fired from John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers for being “too busy”, lays down a simple beat, pure ‘Satisfaction’. Alan Parker turbo-charges Bowie’s Stonesy riff, adding Richards-like muscularity and nuance. Bowie leaves a trail of doo-doos leading back to the Stones’ recent single ‘Heartbreaker’.

‘Rebel Rebel’ makes off with these stolen goods with ramshackle swagger, like a young teenager wobbling down the street in his big sister’s high heels. “The bass is all over the place,” according to Herbie Flowers, making it reminiscent of both punks – the similarly Stones-derived garage that Lenny Kaye curated on Nuggets and the DIY din to come. ‘Rebel’’s manhandled rock & roll predicts ‘Boys Keep Swinging’ with its equally lopsided Visconti bass line.

A Top 5 hit when released on February 15 1974, nine years before ‘Let’s Dance’, ‘Rebel Rebel’ exhorts you to do the same. What’s easy to forget, when reeling in the raucous androgyny, is the song’s kindness. It directly addresses the outcast in the song and the one listening, placing a paternal hand on their shoulder like the homework-burning dad in ‘Kooks’, gently reassuring the boy/girl that more than their hair is alright. Even Lester Bangs was seduced, bemoaning the fact that Bowie rarely let himself be this simple. So cocksure of its own irresistibility, it just repeats itself, doubling up the verses, a mantra of riff, vocal and beat, hypnotically insistent. At the end it uncoils with an ad-libbed rap, rhyming dudes with ’ludes, and paving the way for the hepcat poetry of ‘Young Americans’.

And yet like so many of pop’s rushes of joy (say Abba’s ‘Dancing Queen’), there was just a trace of sorrow in ‘Rebel Rebel’’s eyes. It’s a fond farewell of sorts, to England, to glitter but most of all to the youths that Bowie was a lifeline to. Their identification with him would remain fierce but, the Sigma kids at Young Americans’ playback parties aside, rarely would it be this close again. By the time ‘Rebel Rebel’ hit American radio it had been radically reworked, smothered in phased effects and the Latin percussion of his next soul-based move, as if it couldn’t get de-glammed quick enough.

Jayne County accused Bowie of pilfering. County’s ‘Queenage Baby’ was of indeterminate gender too, delivered to Defries’ Mainman offices, possibly worming its way into Bowie’s magpie ears. But ‘Rebel’’s lyrical provenance could be more surprising. In ‘Grandad’s Flannelette Nightshirt’, George Formby sang about how everybody at the church was “in a whirl”, unsure whether he was “a boy or a girl”, and all “in a mess”. Vaudeville was never far away.

For ‘Rebel’’s video, Bowie had a feather cut and dressed as a pirate, part David Johansen on the Old Grey Whistle Test, part Sinbad The Sailor. The pirate chic winked at Johnny Kidd And The Pirates, anticipated the swashbuckling Adam Ant. The eyepatch Bowie wore was also the prop of David Ogilvy, the 1960s advertising maverick, an Englishman on Madison Avenue who also shrewdly sold his Anglo-eccentricity to his new home.

‘Rock ‘n’ Roll With Me’ opened the original second side, feeling wrenched from the company of the previous song. It was co-composed by Geoff MacCormack, whose piano doodles at 89 Oakley Street inspired a song from Bowie (if they were the opening chords, it sounds like he was playing Bill Withers’ ‘Lean On Me’). A leftover from the Ziggy musical perhaps, with its lyrics of star and audience, ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll With Me’ keeps company with the soul ballads already being written in the Diamond Dogs sessions.

Here neither sax nor piano overflow, elegantly contained in the verses to maximise the sway of the chorus, equal parts stadium-filling rock and Stoned soul catharsis (note the Al Kooper-ish organ). Listen a little closer though and uncertainty creeps in: “lizards lay crying in the heat” like a Hunger City reptile, as if Ziggy’s singing the song he’s drained, as if those black-hole jumpers are already taking pieces of him. A line like “they sold us for the likes of you” demystifies the rapport between star and fan even further, piercing the treacly sentiment like the guitar part’s Manzanera-style jags. A cynicism lurks, borne of his growing awareness of the Mainman reality. All ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll With Me’ needs are the Thunderthighs to make it sound like one of Mott’s gospel-glam odes to the weary world of rock stardom.

The remaining parts of the album are remnants from the abortive Orwell musical. This could be Bowie’s most underrated sequence of songs, brimful of invention, dense with texture, shot through with total immersion and commitment in bringing Orwell’s bleak vision if not to the stage then at least to musical life. Seeping through the Orwellian allegory are myriad anxieties and fascinations. At the centre of ‘We Are The Dead’ are Winston and Julia, their fragile union chronicled by counting lays, like entries in the former’s diary.

The verses are tender, fumbling, real like Lennon’s ‘Love’, giving voice to that domain of privacy, love and friendship that Big Brother has annihilated in the novel. Bowie’s voice is pure feeling, unbearably human. A background vocal hovers – Julia echoing Winston from that golden country. If the verse is love, the chorus is a looming shadow, the fascist climate that thwarts it. The singer writhes like a beast in a cage, the reverb gets thicker, ominous, love itself going down Winston’s memory hole.

The verses’ lyrics are naked, the most direct since Gloucester Road laments like ‘Letter To Hermione’. The chorus’s cut-up lines elude clear meaning and narrative logic, and perfectly evoke the cloaked machinations of power: “The legendary curtains are drawn around baby bankrupt, who sucks you while you are sleeping.” Somewhere here Roger Waters is building Pink Floyd’s The Wall, images as infernal as Gerald Scarfe’s illustrations are planted in the mind’s eye, even Paul Nash’s first world war horror landscape ‘We Are Making A New World’.

The “theatre of financiers… white and dressed to kill” is not merely a stage-set from an overactive imagination but the plutocrat’s playground of here and now (the financiers reappeared with more levity in 10cc’s ‘Wall Street Shuffle’ later that year). And the “press men” of ‘We Are The Dead’ suggest that les tricoteuses from ‘Candidate’ were no longer knitting but writing headlines. It grimly inverts Woody Guthrie: ‘This Land Is Not Your Land’.

At the song’s core is a rock & roll primitivism, closely miked Plastic Ono plod, Sun Studio reverb lacquered on the verse vocal (Bowie scoops up “hope to be shared” as if he were a drunk Elvis). A viper’s nest of studio trickery crawls through the bare-bones basics, a guitar scrapes across the mix like a mechanical wolf in pursuit of the singer’s humanity, a stereo image that paves the way for Visconti/Bowie’s mixing desk assaults on Low to Scary Monsters (it’s actually a Keith Harwood mix, dynamically placing the song’s constituent parts in a soundscape as fragile as Winston and Julia’s love).

There are more lonely ghosts, many from the 1960s: the choral voices that are the new boys, the dogs, then the dead encircling like phantom Beatles. That band’s (and Procol Harum’s) classically tinged elegance comes though in Garson’s electric piano (sent through a Leslie cabinet). Garson’s playing summons all those “complex sorrows” described by Orwell, that “dignity of emotion” from a past that Big Brother wiped out. Bowie’s “scrambled creatures locked in tomorrow’s double feature” echoes Arthur Lee’s “the news today will be the movies for tomorrow” on Love’s ‘A House Is Not A Motel’. Even soul legend Irma Thomas haunts the song, wishing someone would care, time no longer on her side, now waiting for no one.

‘We Are The Dead’ lumbers like ‘Cygnet Committee’, that old death knell of 1960s utopianism. As Bowie reaches the song’s climax, he momentarily loses the definitive article, “We are dead,” he says, reiterated by John Cale that year on Fear. The precarious nature of love in a hostile world resonates here far beyond Orwell’s pages: it could be the French resistance, hearing the occupation on the stairs; it could be the love that dare not speak its name, pressed “through the night, knowing it’s right.” On screen or on record, ‘We Are The Dead’ may be Bowie’s finest performance. This was to be Bowie’s title track for the album, but apparently he was convinced Brownell’s lawyers would not approve. It’s more likely that such pessimism was a step too far.

Then the pulse races and the pace quickens for ‘1984’. Electric pianos could be sirens, could be a glitterball. Imminent disaster glides across the disco floor, courtesy of Visconti’s fluttering strings, relentless rim shots and Parker’s ‘Shaft’-like wah-wah. Originally the song was conceived as part of a medley with ‘Dodo’ for the 1984 musical, worked on at Trident with Ronson and Ken Scott, scene-setting for a musical that never got staged, a tentative step towards soul. The Dogs revamp is more urgent, wah-wah to the fore, strings less winding than Ronson’s original arrangement.

An additional third verse shows how quickly Bowie grappled with contemporary soul – the strut of ‘Fascination’ was barely a year away. By the end of ‘1984’ Bowie responds to the song’s torrid fever with a force that matches the histrionics of his late 70s, the thrill-hurt of the disco diva now consumed by Orwell’s “hideous ecstasy of fear”.

A certain kind of Bowie song is born here; darkly dramatic yet danceable and lushly textured, on Changestwobowie it sat happily with ‘Ashes To Ashes’, ‘Sound And Vision’ and ‘DJ’ (note the Moog sound’s similarity). Harpsichords add novel texture to the doomsday disco (ornamentation later heard under the glitterball on ELO’s ‘Last Train To London’). Here again the singer yearns for “the treason that I knew in 65”; nostalgia was the ghost in the machine of the most ferociously forward-thinking Bowie. Or maybe he was just alive to the ironies of golden-age thinking; 1965 was, after all, the year The Kinks asked where the good times had gone.

‘Big Brother’ is the essence of Bowie distilled; contradiction wrapped in elegant packaging. Again the sound is ripped from Orwell’s pages. A trumpet like Orwell’s,“clear and beautiful… in the stagnant air,” opens the song. It’s backed by choral washes; a fanfare for the arrival of a brave Apollo. Big Brother’s “mysterious calm power” is rendered as beautifully elemental as the sun-scorched vistas of Miles Davis’ Sketches Of Spain (not directly quoted, but a similar sound picture nonetheless).

A jaded libertine’s sad remains are swept aside in the exquisite opening section (dust,roses, powdered noses). It doesn’t return, discarded by the rousing momentum of an Amazing Grace to Totalitarian power. Sgt Pepper-style brass puff unity and celebration, and Bowie’s vocal is one of mad conviction, equal parts testifying soul brother and the dada-esque chant at the climax of ‘All The Madmen’. It gleams with Apollonian light. But it’s artificial, manmade like the Moogs and mellotrons, a fake aureole around a false idol. Scuzzy guitar chafes savagely at the impeccable sheen of the song’s surface (churning Roxy art-rock, Moody Blues-style faux-orchestral heft). A trumpet solo muffles the notes, revealing its synthetic source like the curtain twitching in front of the little man pretending to be Oz’s Wizard. Here is the lure of power and its utterly corrosive nature. ‘Big Brother’ was rarely recreated onstage (except during that other grand, slightly less glorious folly, the Glass Spider Tour). It’s easy to see why: inside it’s vast glass asylum of sound dwells prog, soul, folk and proto-synthpop.

Peel away the anthemic vigour, the sturdy sonic architecture and the almost imperceptible assimilation of sources and there lies a great sadness. A brief acoustic section strips away the soundscape, briefly making sense of Bowie’s assertion that this was his protest album,reminiscent of Hunky Dory but maybe going back to the Beckenham Arts Lab and its quixotic collectivist ideal (a disillusionment akin to Orwell’s with socialism). Big Brother’s monstrous omnipotence is duly noted but an overdose is suggested as an escape from it (something a little stronger than Winston’s swigs of gin). The folky introspection quickly fades as the song reverts back to overdubbed reverence. And the more the song revels in its unwavering devotion, the more sorrow seems to underpin its robust swell. David Bowie was singing to a Big Brother while his own half-brother Terry was in Cane Hill psychiatric hospital; he was singing an ode to a messianic father figure when his real one had been dead four years. Even his new manager hadn’t turned out to be a benign mentor.

‘Big Brother’ is aware of power’s magnetic lure, terrified of its savagery. A wayward decadent cleaves to the certainties of fascism (this was the same year that Nico revived the verboten ‘Deutschland Uber Alles’). Here begins a deeply troubling lineage in English rock, continued by Bowie during his next couple of years, adopted by many a Bowie disciple from Joy Division to The Associates (‘Transport To Central’).

But the horror that follows ‘Big Brother’ suggests an in-built disavowal of all the next few years’ worrying flirtations. ‘Chant Of The Ever Circling Skeletal Family’ is the mechanical and bestial absence of humanity. The black noise that ended ‘Sweet Thing Reprise’ is repurposed as death disco. The overload of the title track returns, shorn of Stones-style good times, a güiro is scraped like a gutter. Herbie Flowers’ bassline burbles along melodiously unfazed by the swirling vortex of sinister sound around him. Voices chant: primordial, atavistic, brainless, the voodoo vocals of Can. Diamond Dogs’ two sides of dystopia – side one’s clamouring for scant resources amid decay, side two’s submission to totalitarianism – morph into one ugly noise, Orwell’s hideous ecstasy of fear. The groove looks backwards and forwards: The Stooges’ ‘I Wanna Be Your Dog’, Neu’s ‘long line’ sped up, disappearing from the autobahn into a black tunnel, Can’s variety and monotony. The latter two were influences yet to permeate Bowie’s work, but they’re prophetically felt here.

It comes to an abrupt stuttering halt, a repetition of “bro” in one speaker, “riot” in the other, as if imitating a locked groove. It’s like the valedictory ta-ras at the end of ‘For Your Pleasure’ on an amphetamine rush, the run-out groove of Sgt Pepper minus the psych-smiles, the stun-gun close to Cooper’s Killer, the sound of ‘Dead Finks Don’t Talk’ leaking down the corridor where it was being mixed at Olympic. The Vorticists’ Blast manifesto. It was a jolt, a waking nightmare, a grim warning from the future.

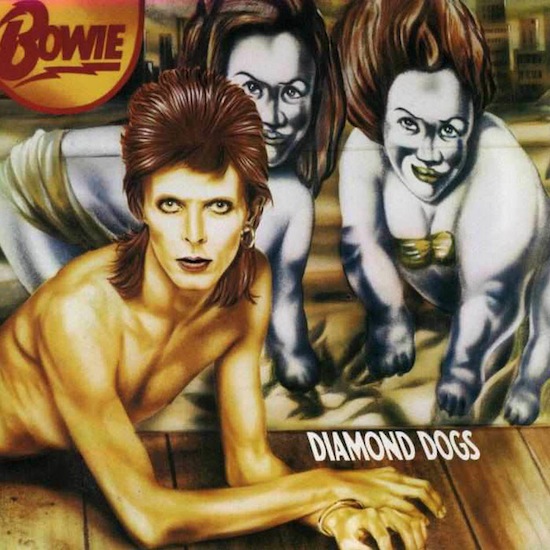

There was one last thing that Bowie stole from the Stones: their cover artist. Guy Peellaert had been commissioned to paint the sleeve of It’s Only Rock ‘n Roll, a move the usually shrewd Jagger informed Bowie of. At a Terry O’Neill photo session, Bowie cajoled the Belgian-born painter into working on Diamond Dogs, which made it onto shelves five months before the Stones’ platter. Unsurprisingly, Bowie’s guest vocals on the Stones’ title track never made the journey from demo to final cut.

Peellaert’s work had recently featured alongside Nik Cohn’s text in Rock Dreams, where images of rock & roll legends are depicted in ways that heighten their rebel energy, iconoclasm and subversion (the Stones in Nazi drag, Jim Morrison and Roy Orbison as leather queens). The images maximised the legends’ subcultural and subtextual meanings – the things Bowie had brought out as Ziggy.

Martin Scorsese marvelled at the painter’s ability to preserve the mythical aura, the ominous danger and the “wild instability” of rock stars (Peellaert later painted the Taxi Driver poster). They are either in tableaux at the centre of things or isolated, hiding in limos behind shades, scared and lonely. In one, an anxious Lou Reed wonders when Dracula (or rather Bowie, in the background) will strike. Peellaert’s photorealist style riffs on American greats Hopper, Lichtenstein and Rockwell, but blends it with something more lurid, gaudy and grotesque, towards the surreal.

Like Bowie, Peellaert stockpiled a vast array of material from a plethora of sources in his Paris apartment. For Diamond Dogs, he worked from O’Neill’s photo, itself inspired by a 1926 picture of Josephine Baker in Paris – another star whose eccentricity was embroidered from isolation, a star whose pet cheetah had a diamond-studded collar.

Bowie is transformed into half-man, half-canine, supine on the floor, inscrutable as the sphinx, staring out with a gaze that pursues you like Big Brother’s poster.The backdrop is a circus sideshow, a Marvel comics recreation of Tod Browning’s Freaks. Behind him are two female grotesques, adapted from a Coney Island carnival featuring Bear Girl and Turtle Girl from the Cavalcade family. Originally the cover also said “Alive”, the standard advert for “the strangest living curiosities” at freakshows. Bowie’s name took its place. Freaks had come with a health warning in the 1930s. As the Diamond Dogs image loomed from billboards across America, it’s likely that many a concerned parent thought Bowie should come with one too. Another Peellaert portrait was intended to adorn the inner gatefold, a gaucho-clad Bowie with a leaping great dane, Walter Ross’ 1958 bio-fiction on James Dean, The Immortal, at his feet. It was replaced by Leee Black Childers’ photomontage.

The sleeve came at a time when rock went cartoon crazy. Elton John ’s Captain Fantastic, Mott hiding in Kari-Ann’s hair for The Hoople album, Lou Reed’s Sally Can’t Dance – all with illustrations that took either glam’s superhero fixation or selfconscious pop-art presentation to the limit. That year, Kiss released their debut album and were mannequins with mass appeal.

Oscar Wilde once said that art which divides critical opinion is complex, vital and new, and Bowie’s 1974 release split the jury. Rolling Stone loathed it (“murky and tuneless”), Lester Bangs in Creem laughed at its pretensions but conceded that Bowie was indeed a great producer and a compelling guitarist. Ian Macdonald in the NME said it “could be the Dark Side of the Moon of 1974,” aware of the existential anxieties and sonic architecture behind Dogs’ shock schlock. Ronson was missed, but the tension and release of his guitar playing was now part of the whole music’s structure. Those wondering where Bowie’s supple melodic ease had gone needed look no further than Ronson’s album to discover it intact.

Despite the lukewarm critical reception, Bowie finally made the Top Ten in America. His oddest record thus far hit Number 5 there, a year before the soul-boy makeover crossover. Perhaps all that groundwork with touring Ziggy had reaped dividends. Perhaps America, reeling from the Watergate scandal, split open by Vietnam, was ready to embrace King Freak. Maybe America was hypnotised by those steely eyes staring out at them, direct and determined where the young man of just a couple of years ago on Hunky Dory had gazed out dreamily. (The deep androgyny certainly didn’t work for Jobriath, a gifted, mercurial singer-songwriter who with manager Jerry Brandt attempted to out-Ziggy the Bowie-Defries model. Vast billboards were erected for him. They quickly came down.)

In the UK, Dogs sailed to Number One for a four-week reign, briefly slicing through The Carpenters’ mammoth stint at the top with their The Singles 1969-73; it was a lightning bolt slashing through the loveliness. But Bowie was no longer there. He left London on 29 March, never to return as permanent resident. When the SS France docked at New York, RCA exhumed the Ziggy corpse once more, releasing ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide’ as Bowie checked into the Sherry-Netherland hotel. He moved further from Angie and the London that had shaped him, and closer to soul music, American stardom and the cocaine that was flowing into America. This stuff was industrial strength. It put holes in Bowie’s brain.

For the Diamond Dogs tour, Hunger City was brought to life in a lavish spectacle, melding Broadway and German expressionism, Wiene’s Dr Caligari and Lang’s Metropolis. Every theatrical rock show since owes something to its innovations: Kate Bush’s Tour Of Life, Madonna’s Blonde Ambition, the Pet Shop Boys’ Performance. Ziggy was finally laid to rest, replaced by a new guise, part Harlem hepcat, part Sinatra-Hepburn Hollywood; mullets and leotards were gone, quiffs, braces and ice-blue double-breasted suits were in. Reports in Disc promised it would make it to London’s Wembley Empire Pool, but it never did.

Bowie planned to film Diamond Dogs, but beyond storyboards and hotel footage of a miniature Hunger City model, this never materialised. Post-Clockwork Orange gangland cult films like The Warriors visualise the music’s campy menace, Starlight Express got the rollerskates that Bowie had planned his characters to have (“because of the fuel crisis”).

Hunger City didn’t last long on the stage either, replaced by a stark, soul revue show, reflective of what would become Young Americans. Naked new material (‘It’s Gonna Be Me’, ‘Who Can I Be Now’) emerged but would miss the final cut, replaced by collaborations with John Lennon; the close-to-the-bone autobiography was no longer cut up, but left on the cutting-room floor.

The Bowie of 1974 was a man in a lonely orbit, drifting away from his manager, wife and old friends and foils. He stabbed his cane nervously into the carpet, skeletal and ill at ease on The Dick Cavett Show; he partied in Dylan’s company with the crazed stare of Pink Floyd’s rock casualties; he hid in the backseat of limos, a nightmare vision in Rock Dreams. The year of the Diamond Dog was also Bowie’s 27th year, the age of entry to that ‘stupid club’. Some say he had to be restrained from jumping out of a window. Mott’s Ian Hunter claimed 1975’s solo ‘Boy’ wasn’t about Bowie, but its lyrics sketch a character disturbingly close: photogenic, fractured, blessed, a mess. When Hunter’s new sidekick Mick Ronson expressed his concern with Bowie’s current state that year, it was even harder not to see the parallels.

Things got worse when Bowie headed west to California. But he survived, cheating death perhaps in a way his alter egos could not, fleeing LA and fearlessly making new music night and day. It was Diamond Dogs’ disparate strands that gave him the fuel to pursue his different paths for the rest of the decade and beyond, the soul music, electronic music and cut-ups, the root of future commercial success and creative sustenance. There are also, in its cut-up fragments, signs of a man wanting “to come down right now” and “find an axe to break the ice”, midway between ‘Space Oddity’ and ‘Ashes To Ashes’. He once referred to the record as his “usual apocalyptic basket” but he also acknowledged that it was “more me than anything I’ve done”.

When Bowie truly picked up from Scary Monsters, the cut-ups returned, created from a computer program (‘the Verbasiser’) for the digital age. In 1995 when Bowie really rediscovered his muse on Outside, he singled Diamond Dogs out as one of his favourites, along with Lodger.

And what became of the Diamond Dogs’ spawn? Soon offspring emerged with names like Siouxsie Sioux, Rat Scabies, Johnny Rotten and Sid Vicious, all inhabitants of Hunger City. Slaughter And The Dogs took their name from combining Bowie and Ronson’s separate 1974 efforts. And Diamond Dogs’ jagged edges and broad palette became something of a signpost once the narrow rulebook of 1976 was torn up. Post-punk is littered with traces of its playful spirit and dystopic dread (Banshees, Cure, Magazine, Associates). Numan was always accused of ripping off Low when he actually listened to Aladdin Sane. Listen to Diamond Dogs though and you can hear Replicas and The Pleasure Principle taking shape; ‘Down In The Park’ and ‘Are “Friends” Electric?’ could be coming from Hunger City. And at that city’s outer limits, one could hear the black noise of Industrial music, the scraping, growling cacophony of ‘Sweet Thing Reprise’ and ‘Chant’.

Perhaps English pop’s artful habit of making misery sound enchanting really starts here, “dancing where the dogs decay”. Certainly the layered art-rock of the 1980s, with its uneven genius and infinite variety. must doff its cap to the album’s shuffling of session musicians and overdubs. 1984 brought with it an Eurythmics album of the same name, inspired by the film adaptation. Its talk of sexcrimes and mournful electro-ballads for Julia, in the same year as Frankie’s orgiastic, lustful ‘Relax’ hit number one, really showed that we now lived in Bowie’s universe – two halves of Dogs’ whole. And when Suede’s Dog Man Star barked at the Britpop party 20 years later, a canine in a herd of sheep with its grand ambition and cut-and-paste lyrics, it seemed to be reminding the zeitgeist of something Diamond Dogs had embodied. Conceptual hip hop may well have taken notes from it (Janelle Monáe’s The ArchAndroid). It is also possibly the only record cited as an influence by both Justin Timberlake and Courtney Love.

Where its predecessors shoehorn themselves into rock classicism, Diamond Dogs howls, scratches and shifts shape too much to keep them company (rock ordinaire bores tend to be sniffy about it; Rolling Stone magazine will never rate it). In that sense it points the way forward to Bowie’s late-70s iconoclasm, and certainly the deconstructed rock & roll of the first sides of Low and Heroes.

Diamond Dogs is the last gasp of Ziggy and glam, with the conceptual clout and vast sonic dimensions of progressive rock, the fangs of punk, the strut of soul and the sweep of Broadway shredded by the jarring cuts of Burroughs. It also paints sound pictures with electronics, proof that Bowie knew his way around a synth before Eno entered the building with his EMS briefcase. Perhaps it is one of the 1970s’ key works: a bit glamorous, a bit grim, pulling wildly in different directions. It is a testament to the rock star as more than a false idol or wild mutation – a tarted-up vessel, teasing hip-swivelling artifice, but containing sad messages and strange warnings for the human condition. Like the original sign on the sleeve said, before it got replaced with the more prosaic “Bowie”, like those other strange living curiosities, this carrot-topped canine remains ALIVE.

Originally published in December 2014