Photo by Clayton Cubitt

Ales Kot is a comics writer and a shaman. Like Grant Morrison and Alan Moore before him, and contemporaries like Jonathan Hickman, his multi-layered, consciousness-expanding comics lead you to question the nature of the two-dimensional, printed reality in your hands, and the nature of the more complex (but no less artificial or constructed) reality beyond those pages.

From the self-conscious art-riot of Wild Children – equal parts Lindsay Anderson’s If…., Morrison’s The Filth, and Jacques Derrida’s ruthless deconstructions of the sign and the signified – to his heart-breaking, vividly psychedelic and deeply personal limited series Change, Kot’s creator-owned work for Image Comics has been essential reading.

The ecstasy of Kot’s influences are a huge part of the appeal – chapter titles taken from your favourite albums, dialogue lifted from the lips of your favourite lyricists and philosophers. This pop-cultural theft-as-creation is echoed in his technical approach to the page. Fast-paced, riveting plotting, compelling characters and deeply experimental layouts recall the tightly-wound conceptual brilliance of Warren Ellis. He has a masterful feel for decompressed, filmic storytelling, like Brian Bendis and Matt Fraction. Drawing on influences he shares with these creators – from Lovecraft to Burroughs, from chaos magick to game theory – Kot has been developing a hallucinatory, iconic style all his own.

Zero, his latest creator-owned work, tells the story of a ruthless assassin embedded in the hi-tech conflicts of the past twenty years. It unfolds with a combination of unflinching, documentary-style realism and all the psychedelic flare of a Jodorowsky film. Kot’s spec script for Zero even made an insiders’ list of 2014’s best unproduced pilots in Hollywood. Over on Marvel’s Secret Avengers title, Kot has channelled the zany energy of Warren Ellis’ Nextwave, while taking on equally ambitious philosophical questions – is reality real? Can we ever truly know our friends? Then there’s his cosmic, fully-painted take on Winter Soldier – after just one issue, it looks set to be another title that subtly riffs on the past, while offering a visionary take on the future; with nods to 2000AD, Jim Steranko’s 1960s S.H.I.E.L.D. comics, and pulp 1950s science fiction, often all on one page.

Now that Marvel dominates the silver screen, comics writers and artists are being given room to breathe; to create intriguing blends of high-concept art and experimental writing. Nowhere is this more in evidence than in the comics of Ales Kot. Born in the Czech Republic, a long-term resident of Los Angeles now living in Brooklyn, he has been a poet, a wanderer, a journeyman. But what makes him a shaman? How does he keep all of this crazy stuff inside his head, and how does he let it out?

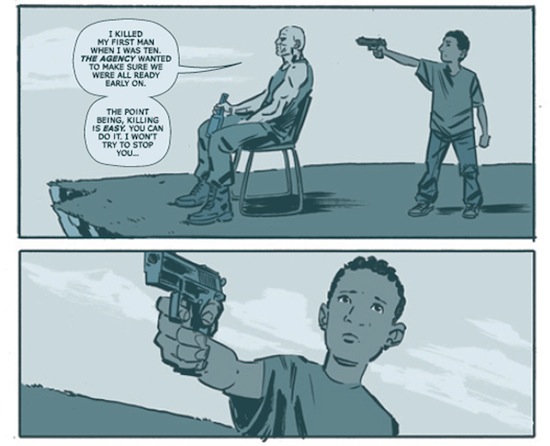

from Zero Issue 8, Art by Jorge Coelho, Colorist Jordie Bellaire

Let’s talk about Secret Avengers. What thinking went into having Agent Coulson, Ultimate Nick Fury and M.O.D.O.K. on a team together?

Ales Kot: Oh, there was no thinking at all. Or almost no thinking. I just threw some names out there. I knew Marvel wanted Coulson and Nick Fury in. M.O.D.O.K. felt natural, too. The only bit of thinking I remember is me going ‘I want more female characters’, and then being like ‘I know nothing about Spider-Woman, so let’s obviously do that, what a great idea.’

Is Secret Avengers as anarchic to write as it feels to read? Is this the kind of book that requires a full-on altering of consciousness to come into being?

AK: I’m basically writing Secret Avengers by making it up as I go along. It’s very… I don’t know how to describe my process. A more directed Pollock? A less directed Picasso?

I trust my shamanic qualities. If I throw it out there, there’s a reason for it, and sooner or later I’ll uncover that reason, and then I’ll tie it all back in. Or I won’t. Depends on whether it feels right or not. For example, I had no idea I’d involve Borges until I wrote #7. And it ties in ridiculously well, even backwards! So it’s a combination of analysis and empathy, and using whichever one feels right whenever it feels right.

Does it sound chaotic? It is! And I love chaos! Chaos and order, hand in hand, everywhere. I guess the years of listening to and playing of IDM and breakcore taught me something.

Can you talk about some of the comics or art you see as Secret Avengers’ predecessors? It feels to me like it is very in keeping with the Heroic Age Marvel titles, but it also has a little bit of the wildness of Nextwave. Can you let us in on some of the ingredients?

AK: I initially thought of Breaking Bad and Arrested Development, mainly. [Matt] Fraction’s take on Hawkeye is an inspiring work. Nextwave also. The Borges connection is now obvious. Dadaists and situationists. Ian Bogost’s Alien Phenomenology inspired my creation of Vladimir, the sentient bomb. Also Brian Eno, Ben Frost, Charlie Kaufman, Alejandro Jodorowsky, artists who do whatever they want because they know that’s the purest way of expressing your personal truth. Kanye West. What you gonna do now? Whatever I wanna do, gosh, it’s cool now!

Secret Avengers is also, unmistakably, an Ales Kot book. A comic that questions its own reality and authorship frequently. In terms of your growing body of work, where does this fit thematically, personally and artistically?

AK: I have to do Ales Kot. Everyone else is taken. Secret Avengers is the second part of my war trilogy, which is an examination of the war meme through comics. The trilogy begins with Zero, which began as a a tragedy, then continues with Secret Avengers, which began as farce, and ends with Winter Soldier, which is a combination of both. It’s my way of talking with myself and with the world. Discussing and working through war and violence. Through their consequences. Through the worlds their narratives bring, and other options, and how we interact with them. What can change and how. It’s limited because I am barely a writer at this point – I just got started. It feels like I’m just warming up.

The whole trilogy is hugely important to me. Secret Avengers is my way of seeing I might be able to pull off anything I want to pull off in fiction as long as I follow my truth. But then again, which project isn’t that? Even the one where I didn’t fully succeed, Iron Patriot, feels important precisely because it showed me what happens when I second-guess myself too much.

Fiction’s transformative. People who say otherwise simply lack the understanding of how fiction and the world constantly interact. Everything we do is a story. Everything is belief, also, I suspect. So when Adam Curtis makes a case for us not believing in anything right now, perhaps that’s a good place to be… precisely because the awareness of the lack of universal meaning can be followed by the realization that each one of us can create our own meaning. By combining and uniting these meanings we can create communities that perhaps go with the universal flow, instead of trying to piss against the wind, and being surprised when our own warm yellow urine hits us in our collective face.

from Zero Issue 2, Art by Tradd Moore, Colorist Jordie Bellaire

This technique you use – revealing in fragments, through glimpses – is intensely psychedelic. You mentioned trusting your ‘shamanic instincts’ – Zero feels very much like the tale of a shaman forged by conflict and war. What can the shaman tell us of war? Is shamanism an alternative to war, or a lens through which to view it?

AK: What can the shaman tell us about war? Well, in the case of Zero, if your reading of it is correct – and I maintain every reading is correct – you’ll have to read further to find out. I’m not interested in imposing any secular vision on people experiencing it. In my case, if we posit I am a shaman – and why not, I am, at least one in training – roughly 90% of violence in the world is perpetrated by men. We also start most wars.

The bleak male rage is the “black thing" war veterans with PTSD talk about. To quote Alan Moore’s 25,000 Years of Erotic Freedom, sexually open and progressive cultures such as ancient Greece have given the West almost all of its civilizing aspects, whereas sexually repressive cultures such as late Rome have given us the Dark Ages. We live in a world where we are taught to be afraid of sexuality but we accept hate and violence as normal parts of our daily lives. We can show a head torn off in a comic without a problem but a woman’s nipple gets people upset. It’s time to change that narrative.

In order to understand what is happening I posit that the root factor of violence is often shame. The church or the government (what’s the difference, really?) tell us what we can do and can not do with our bodies, which parts we can show and which parts we can not – and unless we’re harming other people, there is never any need for that. What then does such repression do? What is the aim?

I posit that the aim is to create soldiers. All the unspent energy has to go somewhere. Sex dissolves barriers. War creates them. As long as we stay unaware of our conditioning, we might be processed by the machine. A culture that puts war on a pedestal and fears sex and nudity is a culture that desires death and not life. I mean, that’s easy to figure out.

How to get out of it? Exploration and dissection are perhaps always the first moves. Identify the systems and then act. A healthy dose of screwing also helps.

As for whether shamanism is an alternative to war, or a lens through which to view it – why not both? I’m all for holistics. Alchemy! Blending of opposites! The truth of the matter is, I don’t know how to answer your question past that. Zero is my exploration of the war meme, my exploration of many of the things I mention above, and I am still writing it, still exploring.

from Zero Issue 10, Inside Cover, Art by Michael Gaydos, Colorist Jordie Bellaire

The maturation of a species, of a character, of a concept or an idea (on a viral level), seems to permeate your work. What role do you think comics can play in the maturation and evolution of human culture as a whole?

AK: The diversity of comics is increasing. The diversity of comics characters is increasing. Is that reflecting the movements in our entire culture? Because our culture is changing – it’s changing constantly! That’s the beauty of life and the horror of it – nothing is immune to change. I choose to find beauty in most things, although I am aware of doing so from a place that is rather privileged. However, being privileged and being shielded are two different things. I am not shielded in the slightest.

I grew up in the Czech equivalent of mid-80’s Wales. I was severely bullied as a kid, I was repeatedly told I wouldn’t amount to anything. I had a gun pointed at me when I was ten. I had to navigate an environment where people who would easily kill people moved through the world at the onset of democracy and cutthroat capitalism in the heavily industrial and unemployment-ridden part of the Czech Republic. I carried a ton of unprocessed ancestral history that involves direct encounters with two world wars, deaths, misery, and plenty more. But I also came face to face with other narratives, and thankfully I picked the ones that would benefit me and also others.

Change is one of my core interests. Change is a constant. The beautiful thing about comics is that they are just words and pictures, and even words are actually pictures with certain universally understood and agreed-upon meanings that form into various languages. So everything is actually comics to me. I’m not kidding. Seeing life through my eyes is a quite fantastic experience.

I believe comics are one of the art forms that can help us transcend the death of imagination. When schools become death zones of imagination and the citizens are attacked via a complex Democrat-Republican system that perpetuates itself by not offering any other option but a dualistic black and white narrative, we need to utilize every peaceful weapon we can find.

Both parties support tax cuts that serve the extremely rich and harm everyone else, while simultaneously destroying programs for the disadvantaged. Both parties support militarization of everyday life. Large amounts of both parties support the destruction of public education and critical thought itself. The eradication of unions. Instead of creating a democracy in the public interest, these systems create a political and economic system controlled by the extremely rich and decidedly near-invisible. Thus we find ourselves in a consumerist-military narrative that tells us it’s each one for ourselves, we should censor ourselves, we should give up our freedom. For what? For the imaginary greater good that never arrives, because it is an illusion created to attract you into a trap.

Fuck that.

Henry A. Giroux names this complex a ‘disimagination machine.’ It tells stories that attempt to indoctrinate us with hate for community, public values, public life, and democracy itself. History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes… The country America resembles the most in these days, at least based on what I have read and discovered, is pre-WWII Germany.

To counter the disimagination machine I believe I must – we must – not only expose it for what it is, but also create narratives and visions that are true to our own deepest selves. Through our connection with memory, imagination and consciousness we learn to be engaged citizens. Or we can be sheep led to slaughter.

We are – right now, every day, and this never ends – producing our culture. Every word counts. Not just what we call art or politics, but everything. The politics of everything, of every act, of every gesture, of every word. A language of critique, kindness, possibility. A language of genuine change, not a temporary promise of change as a way to promulgate radical neo-capitalism. We require good housing, education, living wages – we require a good long-term approach to our entire universe. We need to show that there are alternative narratives. My work in comics is concerned precisely with this. Not just with this – but it is a large part of it.

Comics are one of the many ways to create new narratives that overgrow the disimagination machine by proposing more attractive alternatives. These alternatives are rooted in my own personal changes. As my perception of the universe perhaps reflects my perception of myself, I strive to unblock past traumas through therapy and art and release unwise beliefs. As this happens I show the progress through the art. Sometimes this requires diving deep into the abyss. Comics – and not just comics, but any art form – allow this.

What is specific to comics – one of the things – are the empty spaces between the panels. These spaces are pure imagination. By interacting with a comic we fill the space with our imagination, we engage our senses, we recover our senses, we learn to see more, hear more, feel more. Comics, when at their best, open up our imaginations. And when we apply will to that imagination, to the sense that all is possible – who knows what we can do long-term? I strive for a better world for everyone. Every single person on this Earth is my brother and my sister.

from Zero Issue 1, Art by Michael Walsh, Colorist Jordie Bellaire

Zero feels immaculately researched, so full of textural depth about weaponry, tactics, counter-intelligence. What was it like submersing yourself in this level of detail about a thing which is sometimes horrifying or shocking to study? To what degree is Zero an aesthetic reflection on war, and to what degree is it driven by knowledge and research?

AK: We are submersed in this! The news! The narratives! You know this. You see it. We all do. Zero is an act of orienting myself in the ocean of acid and seeing which way I swim so I can both get up to the air and then out of the Ocean or to a valve that changes the acidity towards something we can all live in.

Living in this is… it feels like a daily trial sometimes, but the hope and the belief in us as humanity and in the universe as a whole drives me. I see so much beauty around me every day. Every moment is perfect in its own way. Even the most horrible things have beauty in them, a vision perhaps co-created by my reading of Baudelaire and Rimbaud at an early age.

This doesn’t mean I want a world where more horrible things happen – but to let them drag me down would be to give up on my belief that the world can be good for everyone. I am indeed an idealist and a utopian, and I believe my body will likely die seeing a lot of things unchanged. But I also believe in the power of imagination and will. I believe I can change myself and the universe responds in accord. I believe my idealism can help me co-create some structural changes.

If I look back at myself in early 2013, writing the first issues of Zero, I knew I wanted to write it in order to dissect, understand and mutate precisely that bleak, dark thing that came hand in hand with anger and violent impulses. I’ve been in fights, and I do believe in the beauty of a consensual fight, which is a way of play. But I do not believe in fight that is rooted in wanting to commit violence. Sometimes I saw an emotion or a thought pass through me and I went – what the fuck is this doing inside me? I need to investigate it. Where is this rooted? Why would a child ever smash ants? Why would a man ever get into a fight when there’s a chance to avoid hurting another person, or himself, or both?

I discovered a lot of this bleak, dark thing had to do with loss in my family. During writing Zero I discovered something about myself, by applying some psychomagic principles. I came to realize that I am a shaman. How could I not be? It’s part of what I do every day. I can enter trance states, I can help myself heal, I can help other people heal. Sometimes I can see spirits. Are they ghosts of other people or other life forms, or are they Jungian externalizations of my psyche? Shit, why not both?

Anyway, loss: I discovered my grandfather on my mom’s side lost his father in Latvia during the Second World War. Then, before he was eleven or so, he lost a girl he loved – she was a Ukrainian prisoner of war who became a part of his family, shot to death by the Russians as they were liberating and “liberating" Czechoslovakia. My grandmother on my mom’s side spent days underneath the ruins of their house when she was just four years old or so, and likely saw multiple atrocities. My grandmother on my father’s side saw her father die of a heart attack on Christmas day when she was about eight – he died in her arms as she stuffed his mouth with adrenaline pills the doctor left behind after his first episode. My grandfather on my dad’s side lost his father early as well.

I realized my family is riddled with unprocessed post-traumatic stress syndrome. Thus I continued my way towards healing myself. And through that, perhaps, towards healing my family as well, and maybe helping others, too.

If everything is narrative – and your comics tend to bleed profusely into reality, making the line between fiction and reality a porous border – do you ever encounter the Grant Morrison mythos quality of seeing your fictions and characters embodied in the real world around you?

AK: Profoundly so, yes, in all manner of ways. The fictions we create are incredibly powerful. I have a quote on the wall – well, I have a few, some my own encouragements and reminders, and then a few by people who are not-me (but really where is the line between our identities? I find it might be just as fluid as the line between reality and fiction…) – such as Christian Wolff, Susan Sontag and… William S. Burroughs. Burroughs is also a part of the Zero narrative. Issue #15, the first issue to be a part of the fourth collection, expounds on this a bit, as you will see if you keep reading.

The Burroughs quote is this one:

“It is to be remembered that all art is magical in origin – music, sculpture, writing, painting – and by magical I mean intended to produce very definite results. Paintings were originally formulae to make what is painted happen. Art is not an end in itself, any more than Einstein’s matter-into-energy formulae is an end in itself. Like all formulae, art was originally FUNCTIONAL, intended to make things happen, the way an atom bomb happens from Einstein’s formulae."

I believe this.

Zero: Volume 2 is out now from Image Comics. Winter Soldier and Secret Avengers are published monthly by Marvel Comics. Collected editions coming soon.