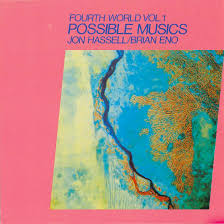

Until extraterrestrial relations are cemented, the term "world music" will be lazy and meaningless. What isn’t world music? A track made from the regular pulses of neutron stars, perhaps? David Byrne, one of the first advocates of the genre, famously told the New York Times why he hated world music, describing it as a name for a bin in the record shop for stuff that doesn’t belong anywhere else. Ambient pioneer Brian Eno and trumpeter Jon Hassell’s 1980 album Fourth World Music Vol. 1: Possible Musics was a template for this belief. The origins of Talking Heads can be heard in this weirdly oppressive piece of non-conformism, reissued this month thanks to Glitterbeat Records. Just ten days after the album was recorded, Eno and Byrne met up in Los Angeles to record My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts.

Listening to the thumps, clicks and twangs that penetrate Possible Musics‘ five brilliant tracks, we wonder where the fourth world sits on the first, second and third world hierarchy. Exotic song titles like ‘Griot (Over "Contagious Magic")’ and ‘Charm (Over "Burundi Cloud")’ hint towards Africa. In fact, the anthropologically defined fourth world is applied to any nomadic people whose cultures are untouched by industrialisation. Fourth world people do not fit within first, second and third categorisations, and certainly do not fall below a perceived third world. By escaping industrialisation, time also has a different meaning; everything that needs to be learned and understood has already been done so. Hassell explained his aims in a 1993 interview:

"I wanted the mental and geographical landscapes to be more indeterminate- not Indonesia, not Africa, not this or that…something that COULD HAVE existed if things were in an imaginary culture, growing up in an imaginary place with this imaginary music. I called it ‘coffee-coloured classical music of the future’. What would music be like if ‘classic’ had not been defined as what happened in Central Europe two hundred years ago? What if the world knew Javanese music and Pygmy music and Aborigine music? What would ‘classical music’ sound like then?"

As Eno and Hassell drape their cloak of ambience over Possible Musics, the dominant percussion is provided by Brazilian Nana Vasconcelos and the Senegalese drummer Ayibe Dieng. Both had previously worked with Hassell, and both give authenticity to the kind of world music modern enthusiasts of the genre will appreciate. ‘Ba-Benzélé’ draws its inspiration from Central African pygmies, creators of a well trodden indigenous sound; Herbie Hancock’s percussionist Bill Summers similarly imitated pygmy music with his beer bottle blowing on ‘Watermelon Man’. More exciting for some will be Possible Musics‘ dedication to the Minimoog synthesiser, an instrument that stirs up a hilariously ’80s, ‘aliens are coming!’ atmosphere.

The whole album taps into some deep psychological urges. People have always and always will feel compelled to drum, chant, clap or pluck a string under tension, perhaps an animal hair or an elastic band. To describe Hassell and Eno’s thickly layered interpretations as a "wall of sound" would fit, but there’s nothing inanimate here; this wall breathes excitement, and is underlined by a heart-pumping, stick-whacking, distinctly human pulse. If the universe-trotting monolith from Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey could appreciate music, this is what it would listen to.