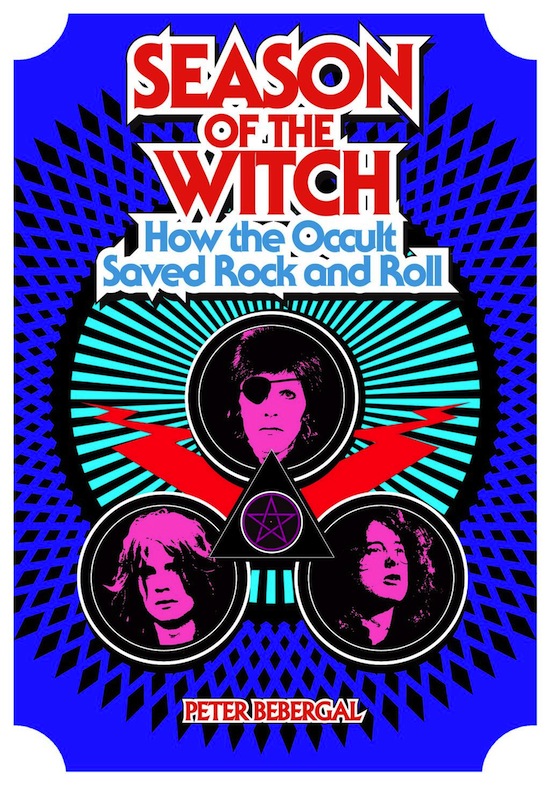

When Quietus writer and author Peter Bebergal first explored his older brother’s record collection at age 11, he discovered something he didn’t expect: magick alongside the magic. Lurking beneath the surface – or sometimes hidden in plain sight – the occult’s influence on rock & roll was as old as the genre itself. Not only was Aleister Crowley’s photograph emblazoned on the front cover of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band but his occult missive "Do what thou wilt" was also etched into the run-out grooves of Led Zeppelin III. In Season Of The Witch: How The Occult Saved Rock And Roll (Tarcher/Penguin hardcover), Peter Bebergal explores the deep and nuanced connection between rock & roll and the mysterious world of the occult. Drawing on key developmental moments in rock history, from its origins in slave song to the rise of electronic instruments in the 80s, Bebergal creates a rich narrative analysis of the genre and its mystical ties.

The author will be in conversation with Mark Pilkington of Strange Attractor Press this weekend in Manchester at Louder Than Words festival. Ahead of that, we talked to him further about his fascination.

When did you first become aware of a band with occult connections? How deep was your interest in the occult yourself?

Peter Bebergal: I was finally able to trace my interest in occult and esoteric weirdness to a particular moment when I was about four or five. My family used to vacation at Nantasket Beach in Massachusetts. They had, at the time, an amusement park called Paragon Park and the haunted house ride Kooky Kastle. It was my first encounter with monsters, devils, ghosts and the thrill of being spooked. I started watching old horror movies, and my father, bless his soul, started buying me monster models and Creepy and Eerie magazine. During that time I was also sharing a bedroom with my older brother. Being seven years my senior he was prone to filling our bedroom with cigarette smoke, trying on different kinds of cologne and listening to the Beatles’ White Album over and over while he drew strange sigils and doodles on the cover with black magic marker. There was something about the sound of this music, along with Alice Cooper, David Bowie and Led Zeppelin, that seemed to correspond to those gothic and supernatural images I was surrounding myself with.

My brother must have noted my curiosity of the arcane, and began showing me the "clues" to Paul McCartney’s death, the inscrutable sounds of certain rock songs played backwards, and how Led Zeppelin were thought to have made some kind of pact with the devil. Something clicked. It didn’t matter whether or not any of it was true. There was deeper reality that I could feel was spinning out of those records, even more real, it seemed, then the pulpy occult tales in my comic books. It was only a matter of time before I was in the library and bookstores looking for books on magic and witchcraft. When I was 13 I saved my money to buy a hardcover edition of The Key Of Solomon The King and studied the seals and tried to summon spirits. But nothing came close to conjuring the spirits of my unconscious as those rock albums did.

I didn’t know then how far-reaching all this was. And even now I am pleasantly surprised as how much of it as remained, becoming the DNA of pop culture. Just the other day I was getting my hair cut and the song ‘Hey Jude’ came on the radio. I remarked to the barber something about the song, and she asked if I knew that Paul was really dead. She was about twenty, and told me that a teacher in high school had shown the kids how it all had to do with Roman Polanski and Manson. It’s 2014 and it must be that every generation has their go at all the great occult mythology of rock.

Other than the fact it’s illicit, what attracts musicians to the occult?

PB: The occult, as both a collection of practices and beliefs as well as overarching symbolic language, has long provided artists and composers with a grammar for realising a means of pushing up against the mainstream, of creating music and art that is not bound by convention. Just as occult practices provided people a more direct and immediate way to engage with the divine, it made sense that avant-garde and experimental artists would feel a kinship and an inspiration in occult ideas and symbols. Satie and Ravel were Rosicrucians, Mucha was a theosophist, Pierre Schaeffer was follower of Gurdjieff, and William Butler Yeats was a member of the Hermetic Order Of The Golden Dawn. The list goes one. As rock musicians experimented with sound and performance, turning towards alternative spiritual practices and images made perfect sense. It was not enough to be socially and politically rebellious. A spiritual rebellion was needed for a foundation. The occult imagination is one that is heterodox, sometimes heretical. What better way to feel as if your art is charged with a deeper spiritual meaning than to attach it to a spiritual identity that itself has often been about rebellion?

How deep was David Bowie’s interest in the occult? On one hand, he tended to flit from one subject to the next in the 70s but on the other he seems to have been quite well read.

PB: As I say in the book, I believe David Bowie is true magician in the story of rock & roll, the artist who most perfectly realised the definition of magic, both Crowley’s original ("The science and art of causing change to occur in conformity with Will") and Dion Fortune’s modification ("Magick is the art of causing changes in consciousness in conformity with the Will"). The thing I wanted to emphasise in Season Of The Witch is that the occult imagination is not simply about belief or practice, it’s about how the application of the occult became the very method by which rock & roll was often realised. Bowie’s music and performance were a magical practice, maybe even more potent than if he sat by himself in his room and tried to conjure a demon. I think this goes to the heart with my frustration with the occult merely has a belief system. Without art, without some expression of those experiences and those interactions with the unconscious, I lose interest. It’s fun to imagine Crowley at the Boleskine house trying to meet his Holy Guardian Angel, but what is left except the story? The story of David Bowie drawing the Kabbalistic tree of life in the studio when he was recording Station To Station resonates because of Station To Station the album. It’s a masterpiece, and it is partly a result of what was going on in his head as he tried to manage a psyche fractured by cocaine and occultism.

Which rock musicians have been the most deeply and seriously involved in the occult in your eyes?

PB: I think there were only a few bands in the 1960s and 1970s that were "serious", although that word itself is a bit suspect. How much does it take to be serious? Joining a coven, collecting rare Crowley volumes, making a movie with Kenneth Anger or just using tarot cards before a performance? Nevertheless, I think some bands took it more serious than others, such as Third Ear Band and Coven, but then there is someone like Arthur Brown who truly believed his music and performances could function as a shamanic act, that using colour, light and sound, he could weave a spell that would result in some kind of mass transformation. I don’t think until later you have bands, however, that saw their music as a form of magical practice until Coil and Psychic TV, particularly by way of their understanding of the Gysin and Burroughs ideas of the cut-up as a magickal art. It is very powerful, whether you believe in magic or note, that by manipulating tape and video you are in some ways manipulating reality "in conformity with Will".

Don’t a lot of modern black metal bands really leave bands like Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath looking like mere dilettantes?

PB: I don’t think so, because I think Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath actually transformed pop culture. That’s real magick. A band’s adherence to some occult idea, be it LaVeyan Satanism or the Norns, is fine for making a certain kind of music that might have its own dark power, but that doesn’t make them any more "authentically" occult. But what Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath both did so brilliantly was find the perfect balance between mythology and marketing. What is the occult if not a kind of transmission between the audience and the musician, whereby there is a kind of unspoken agreement to suspend disbelief, just as when we watch a stage magician. Black metal bands have a powerful pact with their audience and sometimes the media likes to make hay of it all, but that transmission rarely reaches beyond their subculture. Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath are the ur-text for these bands. Or to take the metaphor even further, they wrote the grimoire that contains the spells for how music can activate the occult imagination. They revealed how perfectly occult symbols activate a part of the psyche that responds immediately, sometimes skeptically, but more often than not with a mix of trepidation and curiosity.

How far back into rock music history does the occult go?

PB: I argue in the book that rocks’s occult roots can be found in the spirituals, songs sung by American slaves, often in secret. While these songs were Christian in their intent, the style, rhythms and movement were taken directly from the slaves’ African tribal past. They might have given over to the Christian promise of salvation, but they needed to worship in their own way, often at odds with what the whites thought was proper. The slaves’ form of worship was seen by their masters as barbaric and demonic. Their pagan-imbued worship was a form of spiritual rebellion, a means to be defiant even as they believed in the Christian creed. In this way, the very sound of rock has its origins in this spiritual rebellion, a sound that is ancient and pagan at its core, rhythms used to conjure spirits, to divine and to heal. Concurrent with this are rock’s folk roots which also have some interesting occult connections such as American folk’s own origins in European pre-Christian traditions. And interestingly enough, the folk music that really would inspire many later American artists was Harry Smith’s Folkways collection which Smith packaged with an aura of magic and ancient mystery. None of these things is the single key that unlocks the whole story, but each of these phenomenon are all part of rock’s occult imagination and each had a role to play in how rock’s essential spirit is governed by them all.

Who are the modern equivalents of Led Zep, Bowie and Sabbath?

PB: This kind of comparison is tricky but those musicians were more than their music. Their lives, the rumours that swirled among them, the album covers, even the performances simply have no equal in today’s culture. Truth be told, look at any early film footage of Led Zeppelin. I don’t think anything like that can be done in quite the same way. Even an attempt at Bowie’s alchemical transformations would appear contrived. A band like Ghost B.C. tries to elevate their mystery and their stage shows are nod to the things Ozzy was doing, but they’re almost an anachronism. It doesn’t feel relevant or enigmatic in the same way. So no, I don’t think they have modern equivalents, at least in terms of how I am thinking about them here.

I think there a lot of current bands that have figured out how to use the occult as a real device, sometimes playfully, sometimes knowingly, but mostly successful. And there are bands and performers that I think have found an authentic way to use the occult as a frame of mind, and their music very effectively evokes aspects of the occult imagination – I am thinking here of Blood Ceremony, Crumbling Ghost, Uncle Acid And The Deadbeats, Hexvessel, Swans, Ragnarok, Cyclobe and even King Tuff, there are really too many to mention. And this says something important doesn’t it, that even after all these decades, musicians are still reaching into the astral planes to draw inspiration, be it just for a gag or for something deeper. But they are both equal in some ways, as they are just part of the occult imagination, a very real and essential part of the human experience.

Excerpt from Season Of The Witch

It’s on his 1971 album, Hunky Dory, that Bowie’s fascination with magic becomes less opaque as he makes reference to things fairly well-known by other seekers in the early 70s. Crowley gets his necessary nod on ‘Quicksand’ – a downbeat song about a spiritual crisis. Bowie’s biographer Nicholas Pegg makes particular note of the song ‘Oh! You Pretty Things’, with its warning that "Homo sapiens have outgrown their use." Pegg believes this is a nod to the writing of Edward Bulwer-Lytton. In his 1871 novel, The Coming Race, a man finds an entrance to the hollow earth where he discovers an ancient superpeople described as a "race akin to man’s, but infinitely stronger of form and grandeur of aspect" who use an energy called "vril" to perform wondrous feats, such as controlling everything from the weather to emotions.

This delightfully strange story might have gone the way of other quaint 19th-century fantasies if not for The Morning Of The Magicians by Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier, first published in France in 1960 and translated into English in 1963, which created a wave of esoteric speculation and occult conspiracy theories still being felt today. The authors were inspired by the writer Charles Hoy Fort, who, in the first decades of the twentieth century, used an inheritance to spend his time in the New York Public Library, collecting stories and data from a wide range of sources, all of which suggests an underlying and connected web of paranormal and supernatural phenomena. Using Fort’s method, Pauwels and Bergier outlined a secret history in which important historical figures intuited their own role in shaping a cosmic destiny for mankind, aliens had visited mankind during the first days of Western civilisation, and alchemy and modern physics were not in opposition. The 70s also needed a messenger who could personify astronomical dreams and occult permutations, a figure of decadence and wisdom who could deliver a rock & roll testament to what it’s like to fall between the worlds. Only Bowie could imagine such a creature.

Bowie’s next release would create one of the most iconic and powerful rock personas of all time: Ziggy Stardust. Forgive the hyperbole, but in what is one of the greatest rock & roll albums of all time, The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars, Bowie subverted the grandeur of spaceflight along with the wonder and excitement over the moonwalk and turned the cosmos into a place of ominous mystery, where fallen alien messiahs would learn to play guitar. Bowie synthesised the spiritual hopes and fears of the seventies without ever resorting to New Age platitudes. Ziggy is not here to experiment on humans, he is here to experiment on himself, seeking forbidden knowledge in the urban wastes of earth.

In 1973, Rolling Stone arranged a meeting between the two poles of cultural transgression: William Burroughs and David Bowie. Burroughs occupied a central place in the underground pantheon. Both gay and a drug addict, he explored these aspects of himself through some of the most challenging and disturbing novels written in English. Bowie was his Gemini twin, a wrecker of mores who was reaping fame and fortune as the deranged but beautiful creature of pop music. Burroughs might have been looking for a way into the mainstream, and might have believed rubbing elbows with Bowie would get him closer. During their talk, Bowie describes the full mythos behind Ziggy, describing a race of alien superbeings called the "infinites", living black holes that use Ziggy as a vessel to give themselves a form people could comprehend. Burroughs countered with his own vision to create an institute to help people achieve greater awareness so humanity will be ready when we make eventual contact with alien life forms.

Bowie’s fascination with alien Gnosticism gave way to a return to the decadent magic of The Man Who Sold The World, particularly with the album Diamond Dogs, one of the most frightening albums of the 1970s. The warning of an imminent apocalypse in the song ‘Five Years’ on Ziggy Stardust is realised in the dystopian urban wasteland where "fleas the size of rats sucked on rats the size of cats". The only hope is in the drugs and the memory of love. The track ‘Sweet Thing’ is a beautiful killer of a song, Bowie’s voice hitting the high notes as if desperate: "Will you see that I’m scared and I’m lonely?" Diamond Dogs might be a fictional vision, but the truth underlying it was Bowie’s increasing and prodigious cocaine use, and an even deeper curiosity with the occult. Supercharged by coke, a drug known for its side effect of throat-gripping paranoia, Bowie’s interest in magic could only turn ugly.

Season Of The Witch: How The Occult Saved Rock And Roll is out now on Tarcher/Penguin

Originally published in 2014