With Halloween here, it’s a good time to give some thought as to what it is that keeps bringing viewers back to the horror genre. On reflection there are four obvious reasons that present themselves. First of all, the realisation that our civilized nature only runs so deep: the moment that the harassed or tortured individual or family rises up and reacts with even greater savagery to the threat before them – the terrifying, but empowering awareness that this dark core of violence exists within us all. Secondly, there is the acknowledgement that some form of death awaits us all and that the horror format offers codified, ‘safe’ ways of contemplating that indirectly. Thirdly, the way in which the whole spectrum of the human imagination is given free rein to be deployed against the forces of darkness. Last of all, and perhaps most importantly, a central aspect to the horror films that really work is an element of transgression of societal codes and cultural mores. The Surrealists understood the virtues of iconoclasm, of breaking down what is codified as law to release the energy contained therein so that ideas and events may be viewed in a different light.

Although such shock tactics may certainly include extreme violence, inhuman cruelty and blood-and-guts gore, definitions of transgression within the horror movie genre shouldn’t stop there and humour also has an important part to play. Horror cinema at its best utilises a language of startling ideas, often best executed at low-budget, guerilla level, celebrating individuality above formulaic repetition and artistry above obviousness. Which is not to say that trashy or exploitative films can’t be effective – indeed, many of the films listed here fall into that category – but what really offends (and not in a good way) is a lack of artistic imagination, the sound of one idea flogging itself to death over the course of 90 minutes. Case in point, The Human Centipede 2. Despite basically having just the one premise, namely the disgusting notion of attaching human beings face to anus to emulate the shape of a centipede, the first film had a certain novelty to it, as well as a riveting central performance from Dieter Laser as Dr. Heiter. The second film repeated this one idea, with the addition of another idea (at this rate Tom Six will have come up with three ideas by the time Human Centipede 3 is released) – that the protagonist of the second film, who is obsessed with the first movie, may or may not be imagining the entire thing. The sequel has one genuinely inventive transgressive moment – a pregnant woman attempting to escape the villain gives birth in a derelict car, the baby becoming lodged near the pedals at her feet in a pool of monochrome rendered viscera – but overall is the poorly executed work of a vulgar opportunist with very little to offer in the way of ideas. Having attempted to define terms, here is a list of ten films in no particular order that go that extra mile to disquiet and disturb.

Bad Biology (dir: Frank Henenlotter, 2008)

News that Frank Henenlotter (the Basket Case trilogy, Brain Damage, Frankenhooker), had a new film to be premiered at London’s Frightfest, with an appearance by the man himself, in August 2008 was an enormously exciting prospect. From the onset of the killer opening scene it’s clear that viewers aren’t going to be disappointed. Jennifer – a photographer and sexual mutant – stands alone at a bar while her voiceover announces: “I was born with seven clits… a female of the future who feeds on orgasms the way you people feed on burgers and fries.” Cut to the primary male character, Batz, searching frantically through boxes of empty steroids, fixing a dose and injecting it directly into his penis, screaming wildly as the plunger hits home. We then cut back to Jennifer, who by this time is having sex with a guy she has picked up, in a barely furnished apartment. As the sex becomes more frantic, she bangs his head repeatedly on the floor until we see blood run out into a pool around his limp neck. Having devoured the contents of his fridge, Jennifer then gives birth to a screaming mutant baby, which she drops unceremoniously in the trash on her way out. This all happens within the first ten minutes. To attempt to deny that this film is trash would be ludicrous and contrary to the director’s own intentions. It is, however, hugely fun, highly inventive, fearless and intelligent trash that really pulls out the stops when it comes to dishing out offence. Henenlotter’s eye for the unique runs through the film on many levels, from the strangely featured, presumably non-actor extras, to Jennifer’s bizarrely manipulated facial portraits: a horror unto themselves. At the film’s climax, Henenlotter delivers a venomously satirical stab likely to reduce fundamentalist Christians (who admittedly would never have made it this far), to self-imploding apoplexy, thereby completing the full spectrum of targets taken in his exploitative sights. Henenlotter battled cancer during the making of this film and announced that it had gone into remission when he spoke after its screening. As insane as his other films were, this one is in a realm all of its own.

Father’s Day (dir: Astron 6, 2006)

Reputedly made for just $10,000 by the Canadian collective Astron 6, this mind-boggling piece of midnight-movie style, neo-grindhouse madness is undoubtedly the jewel in Troma’s diseased crown. Hilariously funny as well as downright disgusting, and replete with the kind of consciously playful retro-cliches and stylistic minutiae that will delight horror fans, this film really does warrant the old chestnut “must be seen to be believed.” The plot concerns three heroes, united by their common tragic family history, and their search for revenge on longtime rapist and cannibal who preys only upon fathers, the fabled Father’s Day Killer, Chris Fuchman. Sporting the immortal tagline “Lock up your Fathers,” Father’s Day manages to readdress the injustice that has primarily seen female characters the subject of sexual abuse in horror films, whilst simultaneously proving that for even the most jaded of horror fans, shock is still a possibility. Even more so than Bad Biology, the first ten minutes of this film deploys images of extreme sexual violence, with some cannibalism thrown in for good measure, that are likely to repulse all but the strongest of stomachs. Whilst the first two minutes contain material as deeply unpleasant as anything in Human Centipede 2, after the initially horrific ten minute mark, absurdities begin to multiply exponentially and the tone of the film becomes transformed into a gleeful procession of demented ideas, effects and textures that also delivers some uproarious moments. It’s a powerful combination, and viewers who make it past the first ten minutes won’t forget the rest of the film in any hurry. Like the film itself, the trio of misfit avengers go all the way when they discover that Fuchman is merely the human host for his true demon form and follow him to hell itself for a final showdown.

Eraserhead (dir: David Lynch, 1977)

David Lynch’s 1977 debut may have none of the graphic content of the preceding entries in the list, but it nevertheless remains one of the most disturbing films in cinematic history. The film conveys a deep, metaphysical sense of disconnectedness from its very onset, Henry Spencer’s head floating against star spotted blackness, a spherical planetoid approaching, a spermatozoon thing wriggling out of his alarmed mouth. A scarred man sat at a broken window pulls a lever and the sperm goes shooting off to land, splashing, in a beautifully rendered silvery puddle set against an obsidian black surround. Lynch’s use of monochrome tones is hugely inventive, matt black delineating the shadowy, decaying environment and glossy black surfaces reflecting light. His use of sound, the constant rumbling industrial reverberation of unseen machines, is likewise completely unique. Jack Nance plays the part of Henry Spencer like a man possessed, with his constantly terrified expression and electrified, gravity-defying hairstyle. When Henry visits his girlfriend Mary’s house, her mother asks him if he’s been having sexual intercourse with her daughter, as there’s now a baby. “Mom,” Mary replies chillingly, “they’re still not sure it even is a baby.” Indeed, the entire film is awash with the fear of fatherhood and even the attempt to eat a meal at Mary’s house betrays an obvious distaste for the reproductive process, the ‘man made’ chickens’ legs pumping up and down as black liquid bubbles out from the space in between. The characters in Eraserhead all act in a shell-shocked, traumatised manner and at first it’s not apparent what specific horror could be the root of their torment, but then it gradually dawns that the horror is the ‘dream’ of normal life itself, of family and children born into an uncaring, diseased and derelict industrial landscape.

The Exorcist (dir: William Friedkin, 1973)

Although William Friedkin’s film of William Peter Blatty’s novel may seem a too obvious choice, and numerous satirical takes on Regan’s demonic possession have somewhat lessened the impact those notorious scenes originally had, it’s almost impossible to overstate the effect this film had upon its release. Inspired by both a real life exorcism he had heard about whilst attending a theology class at Georgetown University, and Roman Polanski’s iconic 1968 film Rosemary’s Baby, Blatty’s novel elicited a $25,000 advance from Bantam Books after the author pitched it to editor Marc Jaffe at a New Year’s Eve party. Blatty’s timing was impeccable, his idea tapping into a zeitgeist that had already found expression in the popularity of Black Sabbath and the Rolling Stones’ song ‘Sympathy for the Devil.’ Whilst Blatty himself believed in the reality of the Devil, and considered the ending of Rosemary’s Baby to be a cop out, William Friedkin, an agnostic, felt that the film needed to shock and terrify its audience in order to make them really consider the concepts of heaven and hell. In transcribing the material from the book, Blatty originally took out the scenes of profanity and masturbation in an attempt to make it more acceptable, but Friedkin objected and made him rewrite it into the script, arguing that without those scenes, the story would lose its essence. With hindsight, it’s obvious that Friedkin was right. The film opened on December 26 to an unprecedented sense of national hysteria. Reports of audience members vomiting and fainting, circulated wildly. One woman allegedly miscarried her baby, whilst another suffered a heart attack. (I remember my own mother, when I was a child, telling me that a friend had told her husband to stay out of the house on the evening she discovered he had a copy of the film on VHS.) Indeed, those scenes with Regan at the height of her possession were unlike anything the cinema going public had seen up until that point. The film itself was very well made, with well-acted performances that were far away from the hammy horror of old and the infamy that accompanied its release changed the way that horror films were perceived by both the general public and the studios themselves.

Audition (dir: Takashi Miike, 1999)

It would be an injustice not to include at least one Takashi Miike film in this list. Although Ichi the Killer is far more of a gore-fest and Visitor Q a depiction of one of the most perversely dysfunctional families in screen history, Audition is the one that really resonates in the mind long after the end credits roll. Audition’s extreme effect upon the viewer is largely driven by a masterful strategy of misdirection that misleads the audience into believing they are witnessing a very different kind of film than the one they are actually watching. Thus the transgressive imagery sneaks up on the viewer, and once the truly unsettling stuff happens towards the end, it catches one almost as off guard as it does the main character. What begins as a gently melancholic tale of Japanese widower Aoyama, who is convinced by his son that he should remarry, turns briefly into a romantic comedy before finally launching itself off the deep end in a deeply disquieting climax. Persuaded by his friend Yoshikawa to search for a new partner by holding auditions as a subterfuge, Aoyama falls in love with the initially submissive appearing Asami Yamazaki. Before long, it becomes apparent that there is something severely amiss with Asami, but by then it’s too late for him to escape a retribution that feels directed simultaneously towards his own masochistic spirit and at the prevailingly dominant aspect of male sexuality in Japanese society. Recently the news has emerged that a Hollywood remake is being planned, with Australian director Richard Gray at the helm, which will reputedly be more focused on the original novel by Ryu Murakami. It’s impossible, however, to imagine any remake of this film surpassing the original. One has to wonder why anyone would even bother trying.

Possession (dir: Andrzej Zulawski, 1981)

Hacked to bits at the time of its original American release and banned in the UK during the backlash against so-called ‘video nasties’, Zulawski’s masterpiece of marital disintegration gone horribly wrong is finally achieving recognition as the most far-out European art-house horror flick of all time. Isabelle Adjani turns in a performance of stomach-churning intensity as Anna, the increasingly unhinged ex-wife of Mark, played by Sam Neill. What begins merely on the usual level of breakup bad-vibes, rapidly escalates into a horrific descent into madness and extra-dimensional infidelity that sees Anna coupling with a many-tentacled Lovecraftian abomination, designed by Italian special-effects wizard Carlo Rambaldi, best known for the creation of the cute E.T. from Stephen Spielberg’s film of the same name. Zulawski apparently drew inspiration for the script from his breakup with Malgorzata Braunek, and its not hard to perceive that the director was coming from a very dark place when he worked on this film. Possession opens with an image of the Berlin wall, an appropriately iconic image of separation, and proceeds to evoke an increasingly chilling atmosphere, tinged with madness and despair. In one of the film’s more infamous scenes, Adjani goes into convulsions in the Berlin subway, screaming for what seems like forever as she miscarries some unspecified inhabitant of her womb. It’s extremely difficult viewing but far from the only severe shock in store as the film careers towards its crazed conclusion.

I Saw the Devil (dir: Kim Ji-woon, 2010)

Jang Kyung-chul, played by Oldboy’s Choi Min-shik, has been killing for pleasure for many years and getting away with it, until he brutally murders the fiance of secret agent Kim Soo-hyun, thus setting in motion an epic cycle of revenge and escape that threatens to never end. Unsatisfied with simply tracking the killer down and taking his life as payment for that of his beloved’s, Kim Soo-hyun forces him to swallow a miniature tracking device whilst he’s out cold. What follows is a hyper-intensive game of cat and mouse, the likes of which have never been seen in cinema before or since. Every time Kim Soo-hyun torments, beats and nearly kills his prey (each time growing closer himself to the empty inner state of the monstrous psychopath), the viewer thinks “surely he can’t have survived that,” before he’s allowed to recover and the cycle of revenge contains anew. Both leads are played with an intensity of conviction that is utterly gripping and despite its 144 minute running time, the thrills never let up. By the time the ending comes around, the viewer will be thinking that there really is nowhere left for the director to take this that would significantly up the ante. They’d be wrong. As with Audition, news has recently emerged that an English language remake is in the offing, this time to be directed by Simon Barrett and Adam Wingard. As enjoyable as Adam Wingard’s last two films were (You’re Next and The Guest), you have to say: “Guys, just don’t bother.”

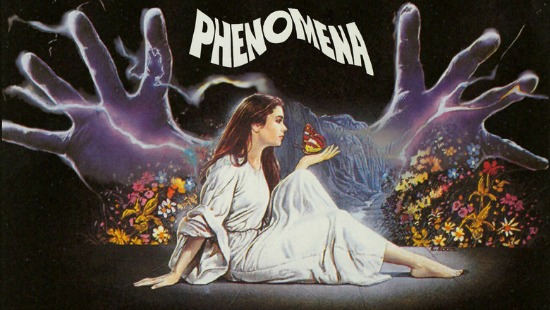

Phenomena (dir: Dario Argento, 1985)

Although critics tend to focus on earlier films such as Suspiria or Deep Red when discussing the best of the Italian horror maestro’s films, Argento’s personal favourite was Phenomena, his crazed attempt to fuse a fairy-tale narrative onto a giallo’s exquisite corpse. Cut by 20 minutes and released under the title Creepers for its American release, the film stars a young Jennifer Connelly in her first major screen role as Jennifer Corvino, a year before her turn in Labyrinth. It also features one of Donald Pleasance’s best performances as forensic entomologist John McGregor and Argento’s long term girlfriend Daria Nicoldi as the increasingly unstable Frau Bruckner. When Corvino arrives at the Swiss Richard Wagner Academy for Girls, her burgeoning friendship with McGregor and her newly discovered ability to telepathically commune with insects, leave her perfectly placed to solve the murders taking place at the school. The film walks a fine line between terror and downright absurdity and it’s not hard to understand why some bemused critics initially dismissed it as a misstep in an otherwise exemplary career. For those of us unperturbed by such delirious flights of fancy, however, its sheer exuberance and insanity mark it as an utterly unique entry in the history of horror, and its deranged ending is simply without parallel, employing a vat of rotting corpses, facial immolation, swarms of descending, flesh-eating flies, a sheet-metal beheading and a crazed monkey with a straight razor. I’ve not given up hope yet, but if I ever see an ending to a horror film that tops this, I will very surprised indeed.

Santa Sangre (dir: Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1989)

Fenix, played by Jodorowsky’s son Axel, recalls the childhood trauma that led to his incarceration in a mental hospital: when he witnessed his father cutting off the arms of his mother, Concha, the fantatical leader of the heretical church of Santa Sangre (“Holy Blood”) before taking his own life. Escaping to rejoin his surviving but armless mother, Fenix becomes her arms as the two embark upon a murderous spree. Jodorowsky has said that he was inspired to retell, in his own inimitable way, the story of Psycho, in particularly the relationship between the killer and the mother which provides his psychological motivation. Jodorowsky’s use of transgressive imagery is qualatatively different from any of the other entries in this list in that he often presents images that would normally be seen as depraved in a sacred, ritualistic context. No purer combination of horror and sublime imagery has ever found its way onto the big screen. Jodorowsky’s playfully anarchic, iconoclastic spirit imbues even the quieter moments with a defiantly taboo breaking attitude, as in the scene where mentally ill patients are given cocaine and taken to visit prostitutes. Transgressive and transcendental in equal measure, this film is a wonderfully vivid piece of surrealistic cinematic art.

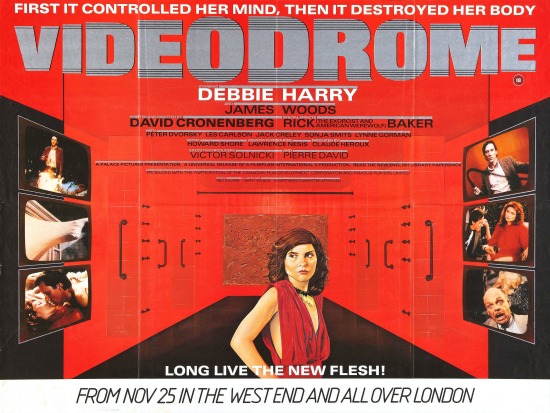

Videodrome (dir: David Cronenberg, 1983)

David Cronenberg’s early films (you can go as far as Crash before they start becoming disappointing), are simply unequalled in the genre. Rabid, Shivers and Scanners have long been firm favourites, but when it comes to sheer prescience of thought, eminently quotable dialogue, expert manipulation of imagery and significant philosophical intent, Videodrome takes first prize every time. Even though it obviously carries the trappings of the era in which it was created – video cassettes and ungainly, box-like televisions – it remains entirely pertinent to the present day. It knew what it was about from the onset, it just took the rest of us a few years to catch up. James Woods is Max Renn, the CEO of a marginal television station who thinks he’s found ‘the next big thing’ when he happens upon a broadcast signal carrying images of extreme violence and torture. When Renn meets Nicky Brand, a psychiatrist and radio host with sadomasochistic tendencies played by Debbie Harry, the chemistry is palpable. Questioned about the extreme nature of some of his channel’s broadcasts, Renn glibly responds that he is providing a service for his viewers to harmlessly act out their darker fantasies. Brand responds by saying: “I think we live in over-stimulated times. We crave stimulation for its own sake. We gorge ourselves on it. We always want more, whether it’s tactile, emotional or sexual. And I think that’s bad.” Whilst Professor Brian O’Blivion (clearly inspired by Cronenberg’s fellow Canadian, the media prophet Marshall McLuhan), offers his own philosophical perspective: “The television screen has become the retina of the mind’s eye… soon all of us will have special names. Names designed to cause the cathode ray tube to resonate.” What seemed merely a dark potentiality in the era of satellite tv and betamax video, appears to have become truth in the age of the internet. Although the media furore at the time of the film’s release focused on the sadomasochistic elements of the Brand/Renn relationship, what remains truly transgressive is that the film, like the Videodrome broadcast itself, has a transformative philosophy at its heart: “Death to Videodrome! Long live the new flesh!”