If Biggie Smalls’ murder hasn’t been described as "hip-hop’s JFK moment" that may only be because the music has been spoiled for choice. But the way the untimely deaths of major figures in rap history have been reported have also perhaps meant that a globally unifying moment hasn’t been possible. I read about Scott La Rock’s killing weeks after the fact, in two very similar pieces that Frank Owen wrote for both NME and Melody Maker; what turned out to be 2Pac’s fatal wounding had an air of "here we go again" to it – it wasn’t the first time he’d been shot, and as he clung on in that hospital room most of us probably expected he’d pull through again; Jam Master Jay’s murder, a little later, seemed the cruellest blow, but he hadn’t truly been in the limelight for a while and the details seeped out like a rumour, a credible account taking days to emerge, the details accumulating only gradually, like a view from a hilltop that you can only piece together through gaps in thick cloud. But when Biggie was gunned down outside a car museum in Los Angeles after a star-studded post-Grammy party, there was that "I remember where I was when I heard" immediacy.

In part, this may have been down to the particular set of circumstances. In March 1997 I was working at the monthly music magazine Vox, and had managed to persuade them to let me write a four-page feature on Biggie for our edition that came out at the beginning of April. His second LP, Life After Death, was due out late in March, and he was coming to the UK to do interviews and promotion for it at the beginning of the month. The interview had been put in for the Monday morning. I was at home on the Sunday when the phone rang.

In the wider tragedy of Biggie’s demise, the fact he was supposed to have boarded a plane and flown to London some hours before the four shots – three non-fatal – ripped through his unarmoured car door probably just seems like a footnote. To me, though, it’s always felt crucial. Why didn’t he make the flight? The possible explanations rarely rise above the banal. In what proved to be his final interviews he said that he’d been having such a good time in California – he’d been there a month, making videos, recording, enjoying himself – that he just couldn’t tear himself away. Following a car accident a few months previously he was walking with a cane; perhaps a long-haul flight just seemed too daunting a physical undertaking. He was enjoying the weather: back east it was cold, in Europe it wouldn’t be much better. He even told people that he didn’t fancy eating European food (of the many American-rapper stereotypes recognisable to the European journalist, this one is a hardy perennial: it’s made all the more depressingly nonsensical when you spend any time at all in the company of American hip hop artists in cities like London and realise that pretty much everything they eat while they’re here comes from McDonald’s or Pizza Hut).

Less understandably, and more troublingly: he’d been warned, both informally and though somewhat more official channels, that he and his Bad Boy Records family’s high-profile presence in Los Angeles wasn’t perhaps the safest strategy considering the specific tensions that were evident in the city in those months following 2Pac’s murder. Perhaps he was emboldened by the realisation that his and his labelmates’ every move was being shadowed by FBI agents: you could perhaps understand some sense of indomitability that might spring from that. Who would be the fool who’d try something with the Feds looking on? The irony – and the tragedy; not to say the horror – of the situation is, that we may never know the answer.

So instead of interviewing Biggie I spent that Monday writing the inevitable piece about the conflicts his work embodied, and the crisis that was enveloping the music as another of its most iconic characters and conspicuously gifted creators was lost. Instead of speaking to the former

crack dealer about the blurring of the lines between life and art, I talked to some of the music’s elder statesmen (Rakim, Kool Herc) about what this all meant for the culture. Few people would go on the record: one person I was able to refer to only as a "prominent east-coast music

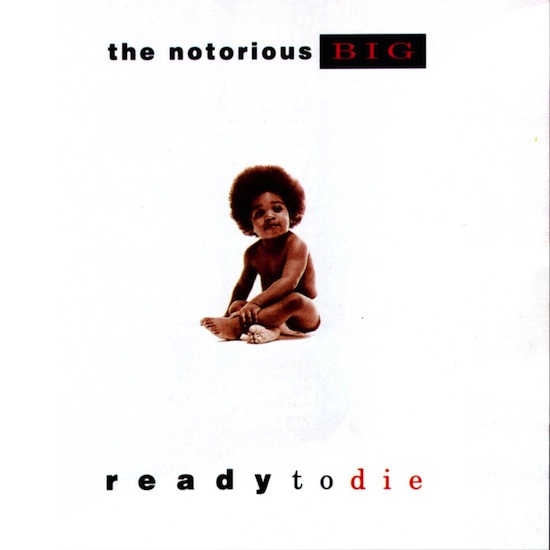

business figure" made the point that "If you’re an ignorant low-life motherfucker you still will be after you got paid from your rap album – money doesn’t buy you a new state of mind." But it would be years later – reading it in Cheo Hodari Coker’s book, Unbelievable – that I first came across the sentence that perhaps best summed up what was going on at that time. It came from A Tribe Called Quest’s Q-Tip, who had been speaking to the New York rap radio station Hot 97 in the aftermath of Biggie’s death. He had told them that: "if we say we’re ready to die, we’re going to die."

Ready to Die was a difficult album to listen to while its maker was still with us, but it’s impossible to hear now without your knowledge of what happened to him two-and-a-half years after its release fogging your vision and altering its context. What it meant and what it has come to mean are two completely different things, but the former is so obscure as to be irrelevant, so elusive we can no longer track it. All we’re left with is the latter: and that’s difficult and conflicted enough as it is.

For starters, what this record appeared to be, and what it stands revealed as today, are two subtly but significantly different things. The LP that no less experienced a judge than KRS-ONE was moved to proclaim the greatest hip hop album of all time is great in no small part for the way

it – mostly – frames a broad, filmic narrative. The opening introduction fills in the back story, with the timeframe sketched through music: we hear a child being born to the strains of Curtis Mayfield, family arguments with ‘Rapper’s Delight’ in the background, and as Audio Two’s still shockingly minimal ‘Top Billin” fast-forwards us to 1988, the child is now a stick-up artist. By the time he emerges from prison in 1993, Snoop in the background, and proclaims he has "big plans", the scene has been set. And what follows – broadly – sticks to the tale of a hoodlum who tries to make moves in the rap game, but, like that perennial gangsta-rap archetype, Scarface, he can’t help but get pulled back in. And yet, despite the trail of angry former lovers, bested criminal rivals and dead bodies he leaves in his wake, what seems his inevitable end comes not from an adversary seeking payback but at his own hand, as the dismal state of his life and the beginnings of a sense of remorse combine to reveal a purposeless future with what he has come to feel is an unlovable and irredeemable soul at its heart. And as we hear his considerable frame hit the studio floor at the conclusion of ‘Suicidal Thoughts’, there’s no mistaking the craft and verve Biggie has displayed while taking us on this hour-long journey.

But the structure of the album, the introduction of the various scene-setting interludes, and even the subject-matter of some of the tracks (the final one among them), were not necessarily part of a single coherent vision by the man whose name is printed on the sleeve. Just as he had to be persuaded to record the tracks that turned him from the underground’s next man to a mainstream pop star (the smoothly aspirational and broadly autobiographical ‘Juicy’, the Snoop/Dre-patterned ‘Big Poppa’), so the idea of a narrative was something Biggie did because his mentor, Sean "Puffy" Combs, suggested it would add depth, and Biggie felt he owed it to Puffy to put a bit of what he wanted in there. Biggie trusted his mentor’s instincts, and was right to do so: but it means that what some of us have spent 20 years thinking of as his grand ideas may not always have been.

The record was pieced together from recordings made over a lengthy period. There is no indication that Big had planned the majority of the tracks as episodes in a larger story. This helps explain how the narrative loses direction and focus about halfway through the album, and may also offer some indication as to why there’s so much time given over to the depressing objectification of women: if he was just trying to set up the "I’m a piece of shit, it ain’t hard to fuckin’ tell" line in ‘Suicidal Thoughts’, then ‘One More Chance’ and ‘Friend of Mine’ are both surplus to requirements when the far more nuanced ‘Me & My Bitch’ shows that the protagonist uses women for sexual gratification but is still capable of feeling real and deep emotions, even if in his relationships with men he’s unwilling to allow that side of his personality to show.

The storyline idea is a masterstroke: as well as lending greater resonance to what are otherwise self-indulgent pieces of gangsta-rap posturing and machismo (take ‘Gimme The Loot’ out of its context and, as bravura a display as it is – Biggie rapping in two personas, with two different

voices, having an animated conversation over Easy Mo Bee’s killer track – it’s just a fantasy about robbing people), it meant that there was plausible deniability for the views expressed in the music. The reception the album was afforded – critically, commercially, by fans – tended not to dwell on the moments where Biggie laid bare the parts of a soul so damaged and dysfunctional as to terrify: and when the focus did land on those elements, it was usually to praise the way the narrator of the story didn’t flinch from dealing with the worst aspects of the character he was portraying, or allowed listeners to reflect on the way societal demands or political mendacity had contributed to an environment that abetted the dehumanisation of a generation. Still, there were moments of curious coyness: given the toe-curling explicitness of ‘#!*@ Me (Interlude)’ – Biggie and real-life lover Lil’ Kim simulating sex on a piano stool in the studio – and the depths plumbed during ‘One More Chance’, where the humour, if such it is, fails to rise above the puerile, it’s baffling that the only word censored on the record is the one that reveals Big’s character wouldn’t be averse to robbing a pregnant woman. Clearly there were some concerns, albeit minimal, about some of the things that are going on in these lyrics. And if they weren’t written as chapters in a longer saga, how can we even guess at what these songs actually mean?

As well as an obsession with sexual gratification regardless of its cost on the people used to provide it, the other problem with the construction of an overarching narrative is the way Biggie weaves the rapper/dealer dichotomy in and out of the song cycle. If you listen to Ready To Die as if it were a film, this is probably its most confusing aspect. Clearly, as he schemes in ‘Gimme the Loot’ or plans bloody pre-emptive vengeance on rivals he is told are coming for him in ‘Warning’, we’re not supposed to take this as documentary. Biggie dealt drugs and spent time in prison, but he wasn’t a killer. Yet the character he plays in ‘Juicy’ is based all too vividly on his own life, while the birth scene brilliantly rendered at the start of ‘Respect’ is his own – mythologised and amplified, obviously, and with a doff of that Kangol in the direction of Ice Cube’s ‘The Product’, but still drawn from the life that he actually lived. Big and Puff wanted to have their cake and eat it: the narrative conceit allows a method of excusing the graphical excesses while the fragments of verifiable autobiography mean that the record succeeds in keepin’ it real. It’s quite an achievement, and it works: up to the point where you want to, as it were, separate the game from the truth.

And so Ready to Die remains simultaneously one of the greatest albums of all time, and an often repulsive document of the kind of personality you hope you’ll never have to spend any time dealing with. It’s brilliant and awful, a record you hate yourself for loving. This, too, is one of its maker’s greatest strengths: he could sell a story so completely you couldn’t see the join between the fiction and the reality that inspired it, leaving you in awe of the artist even as you are

horrified by the thought that the reason it convinces is probably because most of it is based in truth.

There’s something compelling going on in every track, and at times, what Biggie does with the art of rap manages to be unprecedented, formally daring and, even two decades on, unbettered. ‘Gimme the Loot’ has attracted much praise over the years for the vocal dexterity Big showed in

playing the two characters, but as a piece of writing it’s eclipsed by the album’s other solo two-hander, ‘Warning’. Over a track Easy Mo Bee originally made for Big Daddy Kane (the older artist, inexplicably, wasn’t interested) out of Isaac Hayes’ version of ‘Walk On By’, he gives us two sides of a phone conversation in which a friend calls to advise the dealer/rapper of what is either going to be a plot against his life, or – in some ways even worse – a scheme by rivals to take him down by attacking his family or targeting the parts of his empire he thought had been sufficiently well hidden. It’s the detail that makes it work, and even the parts that at first glance seem a bit overdone are absolutely essential. Take, for example, the piece early in the conversation where the caller – Pop from the barber shop – is explaining where the information is coming from:

[Pop] "Remember them niggas up in Brownsville that you rolled dice with, smoked blunts and got nice with?"

[Biggie] "Yeah – my nigga Fame up in Prospect. Nah, they’re my niggaz; nah, love wouldn’t disrespect."

[Pop] "I didn’t say them. They schooled me to some niggaz that you knew from back when, when you was clockin’ minor figures…"

At first you think, why devote all that time to preamble? It’s a short song – the 3’40" run time includes a good minute of sound-effect-and-narrative outro – so why didn’t he make every word count? And then, as you listen again, think on it some more and let it all sink in, you realise that’s exactly what he did. The call has come in, as we’re told in the first line, "at 5:46 in the morning." You’re not awake properly, and it might take a while to be thinking straight, but one of the first things you’re going to do is establish the veracity and provenance of the information. Who told you? How do they know? And – just as vitally – how do I know that I can trust the person who’s told you? In those lines, we not only get given all the information the recipient of the call needs to answer those questions, we get it in a form that we can believe in too. If you’re the friend or underling who needs to wake your boss up at "crack o’ dawnin’" to tell him some bad news, you’re going to want to phrase it in a way that works. Not only that, but, chances are, you want to give him the answers before he asks the questions. So in those lines we’re not just receiving narrative detail, we gain insight into the characters and motivations of both men on the call. By any rational set of measurements, this is sensational, astonishing writing.

[An aside: on the utterly bonkers No Way Out tour (headliners: Puff Daddy and the Family, featuring a huge orchestra, Puffy suspended over the front rows in a metal cradle, and Lil’ Kim writhing on a heart-shaped bed; main support Busta Rhymes; top of the undercard – The Firm, the group formed by AZ, Foxy Brown and Nas; before them, a Brooklyn rapper promoting his second LP, some guy called Jay-Z; and if you got in really early, you’d have caught Puff’s latest protegee plying his slick R&B trade while everyone was trying to find their seats – some kid called Usher. The

between-sets DJ was Kid Capri) that hit a mass of basketball arenas towards the end of 1998, Puffy played this song in the middle of his set. Biggie was there, on a giant screen, his performance culled from the video. The caller’s part was played by Puff, as he had done in the video, but here he joined in on the vocals. He played the part with enough hysteria and desperation to convince that, whatever his shortcomings may have been as a thespian, when it came to channelling his own life and pouring out the pain on stage in front of an audience, he had – has – few equals.]

Not everything is great. ‘Suicidal Thoughts’ has often been praised for its vulnerability, but I’m not sure those claims stack up. For all its jolts of self-awareness (the aforementioned "I’m a piece of shit, it ain’t hard to fuckin’ tell"; "I know my mother wished she got a fuckin’ abortion") there’s a lot of excuse-making and self-pity (the imagined vignette of heaven is rendered as depressing, not because Biggie’s character thinks he won’t end up there, but because he thinks he will, and won’t be allowed to carry on being a thug; the payoff couplet – "I’m sick of niggas lyin’, I’m sick of bitches hawkin’/matter of fact, I’m sick of talkin’" – is close to making out that all his problems were caused by other people). This is one track where we can be certain that Big is playing a role – it’s a piece he did at Puff’s behest and it’s clearly part of the grand design for the plotline concept – so none of this should be read as autobiography. But that means there’s even less reason to excuse his failure to put more into the song to engender sympathy in the listener. For all the shock at the self-loathing and the unexpected denouement to the album’s storyline, it’s easier to agree with the character’s assessments of himself than it is to feel loss at his demise. Maybe that was the point: maybe the pain we’re meant to feel is at recognising that such nihilism can be born, raised and nurtured in our society. But as a piece of art, it misses its target, despite aiming higher than most.

Yet more or less everywhere there’s something going on that’s noteworthy, vital, energised – and none more so than on the final track recorded for the album. ‘Unbelievable’ was all Big – he had to beg a time-starved Premier to craft him a banger, quick and dirty, even suggesting not just the R Kelly track to scratch for the hook but which breakbeat staple to use (chopping up The Honeydrippers’ ‘Impeach the President’ was by no means a revolutionary act in hip hop production by 1994). Premier has recounted how the session took place at his then hit factory, D&D Studios, in Manhattan; and how, initially, he was concerned Big wasn’t taking it seriously. For most of while Primo built the beat, adding stabs of organ pitch-shifted and played manually through a sampler, Biggie wasn’t even there. Occasionally he’d be seen, nodding his head, mumbling under his breath, the expected rap-writer’s equipment – notebook and pen – conspicuous by their absence. Then he’d disappear again. The producer found him in the studio’s tiny back-room lounge, his trousers round his ankles, enjoying the attentions of two women. Minutes later he ambled back into the vocal booth with the entire song written in his head – "chickenheads be cluckin’ in my back-room fuckin’" and all. He’d worked with the best, but Premier was dumbstruck. As well he might be: the whole track is great, but verse two – with a nimble dexterity to the delivery (in a detail that makes the track soar, the big man with the bigger voice proves more limber with the wordplay than Primo’s two-finger method on the sci-fi sample-organ could ever be; the keyboard is off beat sometimes, woozy, uneven – but the vocal has the precision and poise of ballet), some rapper boasts turning to darkly sinister threats with a subtle but clear echo of a scene in The Godfather, and what seems to be a play on words conflating a gun with Heinz food products – could be the best thing Biggie ever did:

"Bee-eye-gee, gee-aye-eee

aka, B.I.G.

Geddit? Biggie

Also known as the bon appetite

Rappers can’t sleep – need sleeping’

Big keep creeping’

Bullets heat sea kin’

Casualties need treat in’

Dumb rappers need teaching’

Lesson A: Don’t fuck with B-I – that’s that

‘Oh, I thought he was wack!’

Oh, come come now:

Why y’all so dumb now?

Hunt me or be hunted!

I got three hundred and fifty-seven ways

to simmer, sautee –

I’m the winner all day,

Lights get dimmer down Biggie’s hallway.

My forte causes Caucasians to say:

‘He sounds demented’.

Car weed-scented;

If I said it, I meant it –

Bite my tongue for no-one:

Call me evil, or unbelievable"

Biggie was one of the greatest to do it, of that’s there’s no question: and Ready to Die remains his masterpiece. Whether it would have been a better album if he’d been able to make just the record he wanted is unlikely: it works not despite its concessions to the marketplace or

Puffy’s instinctive flair for creating something that audiences would gravitate towards, but because of all that. Nevertheless, it leaves as many questions open as it provides answers to. And it remains a record that is perhaps more to admire than to enjoy. Listening to it was always a difficult experience, not just because of what happened to its maker all too soon after its release, but because of the conflicted and often unpleasant characters that he created to inhabit it.

It’s a record that marked an absolute full stop, a turning-point in the music’s fortunes, and a stark warning. Malcolm X was excoriated in certain quarters for saying that JFK’s assassination was a case of "the chickens coming home to roost", and something similar would later be argued about Biggie’s death – wasn’t this the guy who blurred the lines between crime and rap so much that it was impossible to tell where one ended and the other began? Has this music about violent crime disappeared so far up its own backside that it’s impossible for even the people making it to tell where fact ends and fiction begins? Isn’t it time to take a step back?

Yet instead of heeding the lesson, the hip-hop industry turned the pressure up: before Snoop and Biggie, a criminal past wasn’t a prerequisite for rap stardom, but after them, it became a badge of honour. Instead of learning the difficult lessons from Biggie’s brief life, the rap business – and its attendant media, and its consumer base – bit ever more deeply into the fiction that a life of crime was a necessary part of establishing authenticity as an artist. Big had already told us that ‘Things Done Changed’ – and after his passing they would never be the same again. The traditional marker of the close of rap’s Golden Age is usually cited as the release of The Chronic at the tail end of 1992, but there’s a case to be made that Ready to Die, a record that couldn’t have been made without Dre’s magnum opus as a signpost but which is nevertheless founded on the sample-based aesthetic of the great New York records of the turn of the decade, is the last gasp of that era. Certainly, The Chronic, for all its difference, is part of a continuum: Ready to Die is a closer, an end point, a dramatic and sudden full-stop.

You get used to cancelled interviews if you’ve been writing about rap for more than a couple of weeks, and I don’t keep any notes or records of the opportunities missed, flights delayed, people who didn’t turn up, or whatever. Life’s too short, in absolute truth. But the one that I always think of, the one I wish had happened, was that Biggie interview on March 10th, 1997. Not because I’d have written something particularly brilliant, or because I’d have been able to say that I met him: but because, if he’d been in London that day as planned, he’d probably still be here now. Look at his contemporaries and only real peers – Nas and Jay-Z – and you’ll notice that, after dazzling debuts, they only really hit their stride around album number five or later. What would Biggie have done by now? Life After Death was a palate-cleanser, a series of ideas (some good, some less so) that pointed in exciting new directions, some lines drawn under the drama: we see it as a prophetic tombstone because he died before it came out, but if he’d lived it would have more clearly stood revealed as a place-holder, a waypoint on a journey to somewhere else. So I don’t miss the conversation I never had with him, but I miss the seven or eight albums he’d have made by now if he’d lived. And most of all what I regret never having had is the chance to hear one of hip-hop’s most compelling voices and most gifted writers acquiring the depth and maturity his art would surely have grown into as his wisdom expanded to match his ambition and his legend.