"I hate to have to pull this card, but if you didn’t grow up in Minnesota you’ll never fully get this album. So sorry. Back of the bus, please."

This was not about a Hüsker Dü album that’s thirty-five years old called Zen Arcade. A friend said this some years ago in a discussion about another album I adore deeply called Beaster by the band Sugar, led by Bob Mould, previously in Hüsker Dü. I never lived anywhere near Minnesota, have only passed through it very briefly once or twice on transcontinental trips with my family when younger. I’ve kept that comment in mind ever since I read it, because it reminds me about how little I may actually know about something I think I know.

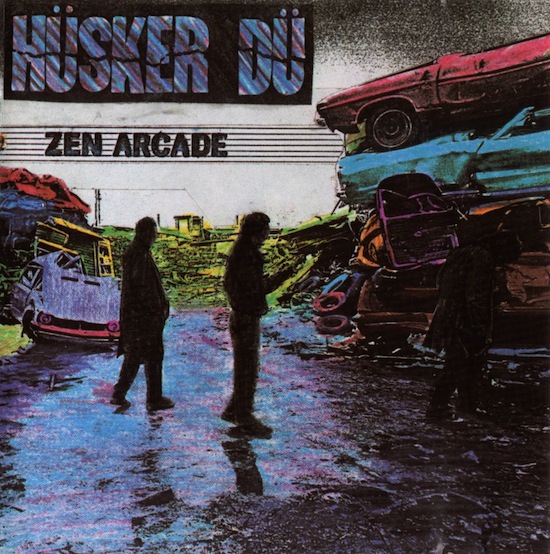

"A record like Zen Arcade — that was a double album that my first group, Hüsker Dü, put out in 1984 — that record has a lot of those rites of passage, trying to separate once and for all from your childhood, as we all want to do when we’re 22 or 23, and not realizing that we can never fully separate from it."

Bob Mould said this in a recent interview tying in with the release of his latest solo album, Beauty & Ruin. At well more than half his life away from Zen Arcade it must seem both strange to him that something like that remains eternally present and at the same time not surprising. You create and if the creation survives and resonates who knows what the impact is. Mould grew up in upper New York State not far from Canada, a whole early lifetime where I spent only three years there and even then I was on the other side of the Adirondacks from him, much different circumstances, much happier ones all around. He’d already left for Minneapolis and college and Zen Arcade came out during the second full summer of my own New York stint, and I didn’t know about it or him or them at all. I think I know something about the album but how little is it, in the end?

It is, of course, not just due to Bob Mould. It’s Grant Hart and Greg Norton and Bob Mould, who formed one of two trios that put out double albums that year on the then-near-peerless SST label – not even the same year, the same month – and both remain astonishing, awe-inspiring. Minutemen’s Double Nickels On The Dime boiled down and focused so much in the moment, in music, politics and the necessity of action in place of comfort to a core point, frenetic, frantic and massively smart, San Pedro’s finest making an album that made bodies dance and slam and minds click further open. And from Minnesota, Minneapolis, Zen Arcade. Not the biggest album from said city that year, not with Purple Rain and all. Perhaps not even the biggest punk album from said city, not with so many going nuts over the Replacements’ Let It Be and approving of the irreverence and the beery emotion and all. Great stuff, but also easier to swallow, not to mention shorter, than what Hüsker Dü did.

But make no mistake, Zen Arcade got so much love too and still does. I don’t think it’ll ever stop getting it. I still keep learning about it from others who hear and know in ways I never went through. A work of art should, at least in theory, speak to all, but it’s no surprise that to some it will say more than to others. It was seen as another step of American punk or college rock or what have you, however you describe it, becoming its own strong thing. Surely you can’t have a double album without being serious, somehow. A young man leaving home, that’s not a concept album about autobiographical footnotes from sages or what have you, it’s more real. Yet maybe it too can be something fantastical or at least beyond one’s own ken, for multiple reasons, a peek not beyond the stars but into a distant house no longer quite a home.

Zen Arcade lets two voices come together to tell a story, or maybe stories, vignettes in the course of a point in life, doing so with guitar/bass/drums, a shoutier, raspier voice in Mould, a warmer, more yearning one in Hart. There’s a fourteen minute instrumental, a short piano instrumental, a song with extra percussion swirls and general noise underscoring a reference to Hare Krishna’s chanting practices, a frenetic acoustic number, other points of variation. But mostly that three-piece-and-rock-out approach, Mould’s guitar often a sheet of blazing noise that feels like a corrugated aluminum wall shattering in your face, other times a queasy backward masked swirl, yet always with hook after hook, Norton’s bass skipping along and digging deep, just standing out enough to matter and add something more than rhythm and bottom end, Hart galloping and smashing and crashing, perhaps Keith Moon come back to life but something else too, still often chasing that land speed record from their first release. No rules reinvented but from the get go with ‘Something I Learned Today’, no need for that either.

I sometimes wondered if maybe another album would have been a good starting point – I ended up with a slew of Hüsker Dü albums courtesy of a friend in college, having only heard of them indirectly from my skateboarding cousin a couple of years earlier. I had heard about Zen Arcade so much, though, and while there are songs to love throughout their career it does seem that whenever I’m thinking of a song of theirs it’s from this one. It’s a tactile pleasure, something immediate that sticks with me. At other points I wondered about the production or the mix, thought that maybe something could be missing or improved. But isn’t that just an example of not appreciating something for what it is? Better to have it than not to have it at all, and relistening confirms that I wouldn’t change a thing.

No major label, then at least and likely even now, would have gone for it. Sure, Warner Bros eventually signed Hüsker Dü and there was a second double album in the form of Warehouse: Songs And Stories, but probably that wouldn’t have happened if Zen Arcade hadn’t already happened first. Were there other pieces of art in general about young men leaving home, musical and otherwise? Rather. Were there any quite like this at this time, with all the silences and elisions as important as the blunt directness? Precious few, and for its time, perhaps nothing else.

I can’t but confess that while Hart has his many moments throughout the album it’s Mould that ended up cutting the deepest for me, at least. He wanted to roar louder than words would let him and he did not have the time for anything else. In the wrong and/or different hands it could be another dude complaining about how his parents just don’t get him, man, before proceeding to get sloppy at bars with bros and wonder why women object to their being pawed and slobbered over. But there was enough fear and loathing going around the country, not just Minnesota and not just in the past still, and a young man’s energy is just that, and the obvious biases and bigotries and their poisonous impacts were well at work AND!

"I WAS TALKING/WHEN I SHOULD HAVE BEEN LISTENING!"

Because generic dude I just outlined wouldn’t have been that self aware in a song like ‘What’s Going On’, except maybe after the second divorce court attendance. The sheer anguish that pulses throughout this album in all in its moments is nerve wracking, a sense of the private conversations in your head suddenly spilled out. ‘Confessional’ seems obnoxiously self-centered, for folk artists of a certain age, and they hadn’t invented ’emo’ as such quite yet in DC. Lost chances, people gone forever, divisions, separations and the obsessive poring over of distant moments – if it’s the melodrama of youth it’s also one that was separate and under real siege. Not necessarily male youth either in the end. Consider the lyrics of one song in particular about the hero, if he is a hero, where "all he does is cry" – that seemingly most unmasculine of emotional reactions, the opposite of ‘BE A MAN’ strictures. The protagonist is male but the door opens to other constructions and descriptions of what that could mean, by implication perhaps but present nonetheless, not just a story about a guy.

The songs from both Hart and Mould still hit like a ton of bricks, not a relentless grind but an explosive release, tempered and leavened by quieter moments to stand out all the more dramatically. ‘Something I Learned Today’, ‘Never Talking to You Again’, ‘Chartered Trips’, ‘The Biggest Lie’, ‘Standing By the Sea’, ‘Pink Turns To Blue’, ‘Somewhere’, ‘I’ll Never Forget You’, ‘Newest Industry’, the penultimate charge and, somehow, cheer of ‘Turn On The News’ before ‘Reoccurring Dreams’ winds out and lets the instruments do the talking. My own undiscovered favorite this time around was ‘Beyond The Threshold’, vocals turned into a slow horror movie invocation of what happens when borders are crossed. So much of what is young man’s music can be just that and ends up being barely related to later. Theoretically I could only slightly relate to this in the first place, as I mentioned at the start. But did it ever dig deeper than I realized, something stronger that time and context.

As I was writing I idly wondered what the closest contemporary UK album would be to this, at least in terms of theme if not sound, and while earlier by a full five years, The Jam’s Setting Sons came to mind, with a similar twinning of the personal and the melodramatic, its own half realized vision of Armageddon refracted through the lost friendships and ideals of youth. Not to mention a similar power trio format, if you like. But as intensely as Paul Weller lets himself show a part of his heart and head on that one, it’s also the difference between losing the bonds you’ve made with others and losing the ones you found yourself involved in to start with – the difference between something you had some say in versus no say at all, until a certain breaking point was reached. The specific shadows of the early 80s have either retreated or mutated in both cases, Thatcherism, Reaganism, its fellow travelers and descendants, but the bomb hovers not so heavily – yet people are still being born now into places where, eventually, they feel they need to leave, to move beyond or else break.

Those breaks are not because they themselves were damaged to start with. Or even that when they arrived their upbringing was incubated by people actually intent on causing damage. Zen Arcade says, in numerous ways, sometimes on the edge of a series of cliffs and sometimes obliquely, that whatever else a departure HAS to happen or else things will turn tragic, perhaps simply even more tragic than it has already been. It’s the start of a story, not an end, and the ending may come in different ways – no wonder it ends with an instrumental, where one can theoretically write one’s own words, a continually blank slate for an epilogue that changes. If an arcade can be a place where you win or lose, then zen – as shorthand or as deeper concept – can see beyond the binary.

So I know this much about this album maybe I can never truly know: what it has to say could be as simple as the shouted words in what remains the song above all else for me, the one quoted earlier about showing that ‘unmanly’ emotion of crying, the summary of the story of the album, as clearly as it can be told, "Whatever." Because it is apology and acknowledgement, reassurance and promise. It’s a small story turned epic and punched through to the heavens and along the plains that is the flat Midwest of reality and projected legend, where everything is the same and it can drive you nuts or it can be another blank slate for another story.

Another Midwest band that left its own resonating impact, Cheap Trick, once said as hopeful sign to dissatisfied youth on the brink of growing up, "surrender, but don’t give yourself away." As Bob Mould says through his protagonist to mom and dad, about to leave them behind out of rage and fear and frustration and sadness, he’s sorry. But as he says to them as much as to an audience who could know, who did know, what was going down, don’t worry.

Don’t worry.

DON’T WORRY.