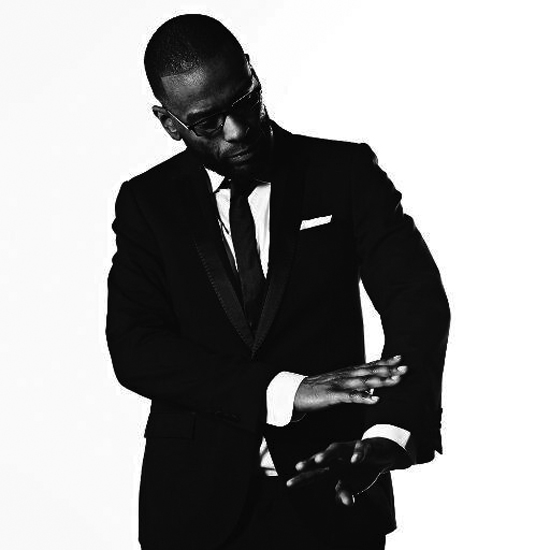

"Mutant music!" bursts Flowdan, with a cackle. He’s expressing his admiration for Kevin Martin’s intricate yet bludgeoning production approach as The Bug, a hydra-headed beast melding dub, dancehall, noise and metal, but the East London MC could just as easily be talking about his own style. Stick on a track or a mix featuring Flowdan and you can identify his presence from a mile off: bleakly hilarious threats, urban life reflections and paranoid street tales, all delivered in that deep, smooth and menacing timbre able to turn on a sixpence from reggae’s patient lilt to dancehall’s fierce funk or the incensed scattergun urgency of a grime or jungle MC.

All of those musical histories feed into his approach. Coming from a Caribbean background, he grew up immersed in sound system musics, cut his teeth as a teenage drum & bass MC, and around the turn of the millennium was became involved with a new mutation of garage that, in the hands of teenage friend Wiley, was fast transforming into its own unique entity – grime. He was a core member of Wiley’s crew Roll Deep throughout last decade, but it was when he joined forces with Martin for a trio of mercilessly dark, brutally funny tracks – the evergreen ‘Skeng’, ‘Jah War’ and ‘Warning’, gathered on the latter’s 2008 London Zoo album – that he started to explode into wider consciousness.

The stark, pitch-black humour of ‘Skeng’ swiftly achieved anthem status across grime and dubstep – drop it on a dancefloor even now and watch the crowd’s explosive reaction – but he’s since settled still further into his musical skin, and 2014 in particular has felt like consolidation and the beginning of a new phase. On Martin’s new Bug album Angels & Devils he plunges still deeper into the void on ‘The One’ and the volcanic ‘Fat Mac’, licked by distortion and crushed metal rhythms. And his Serious Business EP, released a few months ago via Hyperdub, found him working with varied set of producers, including grime veteran Footsie, Masro, and Digital Mystikz’s Coki. ‘No Gyal Tune’ was ferocious, gut-rattling digi-dancehall, while ‘Ambush’ was a pranged-out, weed-addled wander through threatening city streets.

"I look for what’s me in the beat, and if I find that, then it just fits," he says of Serious Business. We’ve met in the food court of Paddington station, and the echoing background ambience of the concourse and regular train announcements meld with the drumming patter of rain on the glass roof. "Coki to Footsie, Masro to The Bug, they could be worlds apart, but they both agree on what’s good, or on what works, even though they’ve got different ways of showing that. That’s why they can produce for me, because all five of us agree on reggae, basically, to cut a long story short – reggae basslines."

In person Flowdan is markedly less imposing than his commanding, intensely overpowering musical presence. He’s thoughtful, funny and quick to reflect upon his own background and the varied influences that feed into his style. "MC’s, whatever they come up with, it’s just them," he enthuses. "There’s so many MCs that are just unique, no blueprint to what they do. Hopefully I’m someone like that."

Looking back to when you were younger, were there any particular moments – revelations – when you were in a club or at a sound system, saw an MC, and just thought ‘This is what I want to be doing’?

Flowdan: There’d be loads. Let’s say from around 1994 – I’d have been 14 – we was heavily into drum & bass, jungle. I never really got to see them perform because I wasn’t old enough to go out, but on the radio I’d be listening to people like MC Det, Skibadee, Stevie Hyper D, Navigator, and I kind of wanted to be them because the music itself resonated with my energy that I had in them years. Even though I’d grown up on reggae music and hip hop and stuff like that, drum & bass just felt unique, original and me. An with the attitude the MCs were bringing to it, some of them weren’t much older than me anyway. So it felt like, ok, this is what my peers do, so it’s what I’m going to be doing. When I got to the age of 16, 17 – the age when I looked 18, so I could get to the raves – I saw them in Hippodrome or something like that, and I thought, yeah, that’s what I want to be doing. The power that they had over the crowd, and the music was just so imposing.

If you didn’t want to be an MC you wanted to be a DJ, that’s just how it was round us. So my peers, we just had plans on doing that, and we were doing that at house parties and stuff like that. I got to like 16 and just lost passion to do that, plus other responsibilities and things came into play – ie life – so myself, I forgot all about it. I just stopped pursuing it really. And it resonated again probably around 2001, when Wiley started to dabble with new sounds, new musics. I thought, ok, let’s start again.

Did you feel a similar energy in the early stuff Wiley was doing then?

F: In grime, yeah. Whatever I’ve just said to you about my youth, Wiley’s probably going to be quite similar, but he just never stopped pursuing the creative side of music. He was a DJ and an MC and a producer, he was always everything, and he never stopped [laughs]. Even though we was together most days, there’d always be a time were he was like ‘I’m going studio’, and I’d say, ‘Alright, I’m staying here’. But one day he came home from the studio with a new sound, and he just said ‘Yeah, and the next song I make like this, I’m putting you on it’. And I said, ‘You sure?’ You know, I gotta dust off the lyric book, and stuff like that… [chuckles] He was like, ‘Yeah, nah, I trust you. Don’t worry about that’. And then from there, we got more feedback from the new stuff – and then, twelve years later, we’re taking it seriously, like a career. [Before then] I’d never gone into the studio ever to make music. My whole thing was jumping on the microphone with the DJ. So when Wiley said ‘We’re going studio’, that was a whole new thing to me.

It’s a new set of challenges, learning to write in song form, rather than hosting a party.

F: Of course! It’s like I learnt the formula. But I knew these things already, I just didn’t know how to explain them. Like when Wiley said ‘You need sixteen bars’, I said ‘What? How long’s that?’ When he turned on the tape and showed me – from this space to that space is sixteen bars – I said, ‘Oh, that’s what we do anyway’. But he said, ‘But now you know the formula, and the maths behind it’. I feel to be an accomplished musician you need to have natural skills – and you probably don’t know where you got them from – but it’s always good to study the science behind what happens and how it happens, the timing, all these things that some people might not even understand that they understand. That helps when you’re trying to have a career. Because, again, it was success that we didn’t expect. So it’s very easy to lose opportunities, or not to make the best of opportunities, if you don’t understand the formula. Simple as that.

There’s a real strong sense of dancehall and reggae influence to your flow. Was sound system culture always in the background?

F: Definitely. Caribbean parents, culture, the food, carnival, Sunday mornings. The music’s always been there. It’s been there for so long I don’t notice it. Then when a different music comes on I notice it; and then obviously, when you’re getting into other influences from your friends that might not be Caribbean, you learn other things, you learn about different cultures and different musics, so then that becomes a part of my make up as well. But reggae’s always been there. That’s the stem. And then as I’ve grown, you just learn that reggae is kind of influential to most musics, so it’s always a good reference point – and if it’s been done in reggae, then it’s probably been done right. Meaning from a production and sound point of view. The first sound system comes from Jamaica, so when you’re talking about sound, MCs, DJs, producers, all of that, it’s had an impact on every music.

And it underpins London music – jungle, drum & bass, grime.

F: It sprouted from that. And usually the makers of it are heavily into reggae themselves. That’s what I’ve found. Especially with the drum & bass guys, MCs and DJs and producers, a lot of their reference was sound systems, they just brought the UK vibe to it, which made it unique in itself. So from knowing that I’ve got an extensive knowledge of reggae, I just thought, well, I’ve got an advantage if I want to stand out. It’s easy to me, I don’t try. I know there’s some people that have studied a reggae formula and they can reproduce it. With me there’s no formula – it’s just the way I am.

At the same time I feel so British as well, in my delivery, and the English terminologies and the way of speaking. It’s still there when I listen to myself, I think, yeah, that’s right, you’re not a yardie [laughs], you’re not quite Buju Banton, but it’s in there, you get what I mean? Where I feel that some people that ain’t as educated on either culture, they can just hear the reggae, because that’s probably more popular when it comes to sound and music and accents. [These two sides of me] support each other, because this is who I am.

My early influences would have been Stevie Hyper D, Riko – ’cause in them days, just like I had tapes of Skibba and Shabba, I had tapes of Riko, ’cause he’s slightly older than me, and he was just in the scene, he was around. So yeah, Riko, Stevie Hyper D, and Beenie Man and Bounty Killer. From there to there.

That’s something I always found interesting about the grime and drum & bass scenes – many of the people that inspired each other were peers. Even as you were saying, Skibadee and the others that inspired you weren’t much older than you, so…

F: You could still meet them, you could still see them. That’s what I mean. That’s what I feel was special for the UK, for me and most of my peers. Obviously the Biggies and the Tupacs were heavily influential to us as well, but speaking for myself, I just couldn’t see me being that. I couldn’t see myself being Stevie Hyper D either! But if I had to choose one, I would have thought I could be him, quicker than I could be [Tupac].

Were you MCing at raves when you were younger?

F: A couple of house parties and bits and bobs. When I was about 16, 17 – any opportunity to get on the microphone. But I was very timid with my approach. You wouldn’t be able to tell, but I was always conscious: ‘Am I ready, am I good? These guys that are on right now are probably the guys that are meant to be on, so don’t come spoil it…’ All these things you’re thinking of. So I didn’t take every opportunity. But when it was comfortable for me, definitely.

And then it was a resurgence, ’cause once we made the grime track ‘Terrible’ [around 2000], within a couple of weeks we had an opportunity to perform it. So that’s when I actually said, ‘Right, I’m going to do this performance, right. But this is not what I’m going to be doing from now on – I’m not an MC, ok?’ Wiley’s like ‘Alright, whatever.’ We did the performance that night, it went very well, I was the highlight of that song, and then… Wiley, once he knows he’s got you, or that something’s going on there, he will press it, and press it, and press it. So then next morning, he’s just saying ‘More tunes! More studio! You’re going to be something.’ And I’m like, alright, cool, whatever. Wiley definitely had the vision and I never did, and I have to be grateful for that.

Did it feel quite natural to fall into your role onstage? So much of being an MC is having a magnetic presence.

F: That’s something that I definitely don’t know the formula of, I can just do it. I’ve noticed that – my presence. Before I was MCing, in any situation, on the basketball team or whatnot, I just can’t help being the person that pisses people off the most, or is liked most. That’s just me. That comes from the fact that I’m always going to express. I will say what I don’t like, I will say what I do like, in the same voice, or in the same energy. So that rubs people up the wrong way or the right way quite easily, but I just feel that you always notice me. You always remember me. And that’s just how it works. Onstage it works more positively than negative, because people are entertained by that factor.

I wanted to ask more about the early days of grime – you were involved with Pay As U Go and then into Roll Deep. Were you guys aware you were creating something new and interesting at the time?

F: Definitely not for me. I [felt] that Pay As U Go was like garage, and Wiley was involved… As I say, from before drum & bass, Wiley’s always been in there to some extent. So natural progression means that Wiley [was] involved in garage now. I was like, it’s nothing like drum & bass, it’s definitely not me – [mimes speaking to Wiley] ‘It’s not you, either!’ [laughs] I was against it. Whatever, they do what they do – Target, Maxwell, a lot of the people that was on Rinse, them guys was doing their shows regular, every week. Once they started doing the garage thing and they was in Pay As U Go, I didn’t pay much attention. But then when I did pay attention – when I listened to it – I could tell it was just on the cusp of when garage gave birth to another style of music. It wasn’t quite grime, but it was another style – and that’s what gave the MCs even more space to do their thing. So now you could get the best out of a Wiley or a God’s Gift or a Maxwell, ’cause it wasn’t garage with vocals getting in the way – it was a new style of music that Slimzee was playing.

I wasn’t aware that it was going to catch on and create a whole culture. But obviously when [Wiley] recruited Dizzee, that’s when I noticed that. Not just the youth – ’cause we was [only] like 19, 20 – but now we’ve got schoolkids, 15, 14, going mad over Dizzee. Going mad over us [too], but Dizzee made it a different thing for them. That’s when I noticed it was spreading like mad – and then obviously going around, going Birmingham, going places. I still wasn’t aware that there was a culture being started until people started saying words that I use, and obviously it was ’cause they’re listening to me on the radio and my music. They’re using my language, my words, that I know I make up from nowhere, and now it’s become part of the curriculum for how we speak as a culture. That’s when I had to take notice, that rah, we’re powerful, and we’re actually contributing something to a whole new thing.

You mentioned before about how you noticed the Pay As U Go stuff leaving more space for the MC. Listening to drum & bass and jungle MCs, then to garage MCs and then grime, you can hear an evolution in the role of the MC within the music. I’m interested in your perspective on how you feel like that role changed during that shift.

F: I feel that there’s two types of performers or artists. It depends on where you come from and what you look up to as well. For me again, sound systems, drum & bass, blah blah blah – there’s a percentage of that that’s hosting, just vibing with whatever happens next via the DJ. Just knowing how to control all this – the DJ, the people, everything. Master of Ceremonies, right? He’s the finishing person. The orchestrator of the vibes, of your whole night. Then you’ve got the guy that can do that, but is also talented enough to make music, to make catchy choruses and touch you emotionally, tell stories. I feel that I’m coming from a place where you had to be able to do both. I feel like my favourites can do both – Stevie Hyper D, he can not say any lyrics and still make you feel a part of the night, and you could be on the radio listening to him at 2 o’clock in the afternoon and he’s saying lyrics, and songs. You couldn’t get no better than that for me, that versatility.

I remember interviewing Terror Danjah a couple of years back, and he was saying that he felt that one major factor in the evolution of grime MCs’ wordplay that’s often less discussed was the influence of US hip hop. As you mentioned, Jay Z, Tupac, Biggie.

F: Yeah, that made us. The MC thing is built here – toasting around the microphone and sound system and whatever. England and Jamaica are very linked regarding the sound system kind of vibes, we’ve got lots of iconic reggae MCs from England – Smiley Culture, Daddy Freddy, there’s loads. So the MC thing is in my culture, as a British Caribbean person – the MC holding mic and just toasting for three hours – that’s in me. And then when I see MCs doing it to music that I could even resonate closer with – ie drum & bass – I feel like ‘Ok, MCing is what you do’. Then you look at concerts, and there’s some crowd interaction but it’s rehearsed – whereas tomorrow’s rave is going to be nothing like yesterday’s rave, but the MC’s still done his job, he still made it work. But I’m glad that we also did grow up on Jay Z and Tupac, because that’s needed as well; that emotion, those qualities, being a wordsmith.

How did you hook up with Kevin Martin?

F: I’m glad that happened. Our Roll Deep manager at the time probably knows Kevin, and Kevin hollered at him and said ‘I need an MC to come to my Mary Anne Hobbs show, I’ve got loads of MCs coming down, I want one of yours’. He asked for a particular MC, with a particular style, which wasn’t me. That MC didn’t turn up, I got the call off the bench! On a musical note, seeing what Kevin was doing was close to what I was doing anyway, but more towards reggae. It had less hip hop and less drum & bass, and more towards the reggae style. When he liked what I was doing and said ‘I would like you to maybe voice a tune for me’, I said ‘Yeah!’ And one tune led to all these tunes.

He’s a person that properly kept me on the rails when I was looking for a way to get heard, or thinking that I needed to do something different to survive in this industry. He was like ‘You just need to actually come directly back to what makes you you, and focus on that, and that will shine through’. He always gave me instrumentals that allowed me to do that, and always told me when I was trying to be too diverse. As coldly as possible as well [laughs], he’s not really a person that minces his words, and I love him for that. I owe him a lot – the fact that he just gave me the confidence to believe that what I was doing didn’t need to be changed. It’s not broke, don’t fix it, just go further in, and develop that more.

[Working with Kevin] is a back and forth [process] – very seldom he likes [a track] first time, but there’s been a few tracks such as ‘Skeng’, he liked ‘Jah War’ first time because he kind of requested those lyrics. There’s a track called ‘Fat Mac’ [on Angels & Devils] that I actually wrote in front of him, wrote with him.

That track is great. It’s so dread out.

F: [Laughs] He’s trying to crush himself, basically, trying to better his own work. That was actually one of the first songs where I stopped writing – as opposed to pen and paper I just think and say now, just having fun, working through it, using a different flow. He’s been asking me to slow down, and I won’t, because that’s when I start thinking ‘It’s too reggae now’. So with ‘Fat Mac’ you hear the flow’s totally different and spaced out. The song just come out like a freak of nature, it’s so different to anything we’ve done. ‘Fat Mac’ we know is a freak of nature – nothing’s going to sound like that from us to ever again. And we can say that about ‘Skeng’.

I wanted to ask about ‘Skeng’. It’s amazing how much of an anthem it’s become.

F: [Shakes head in disbelief] Fucking hell, man…

It’s still played in the Quietus office every week. How did that come together, do you remember much?

F: I remember everything about it. I’m in the studio with Killa P, I brought Killa P there to do some dubplates for Kevin. I’d done what I had to do – ‘I’ve come to the studio to do work, and now I want to leave‘. Kevin was like ‘Hey, I’ve got another instrumental!’ and I was like, ‘Pffft, tomorrow. Another day.’ Killa P had a different outlook on it all, because he wasn’t where I was in my career, so he was like, ‘No, I’m game, I’m not leaving, I want to do more tunes. I’m not leaving.’ I was like ‘Ohhhh please man!’

So Kevin puts it on. Killa P don’t take much persuasion to jump on any track [chuckles], and he does the first whole intro – phenomenon one to ten! – and I have to say, he was definitely freestyling, he was making it up as he went along. He’s a genius! Done all that, and I was actually liking it, I was thinking, ‘This guy [Killa P] is amazing, fucking hell man, he’s sick, we’ve done all these songs, now he’s still doing this, yeah he’s a G – but I still want to go.’

It gets to the end, and Kevin’s like, ‘You have to jump on this.’

I’m like ‘Tomorrow. What he’s done is sick. Tomorrow‘.

‘Yes, cool … Just put something on it. Just give us a little viber so I can listen to it when you guys go.’

‘Alright, gimme the headphones… "SKENG … SKENG … SKENG … ME UM KILLA MAN BUSS OFF THE BIG SKENG". Haha, yeah, that sounds funny!’

‘Just do that for the whole way!’

I don’t normally chat like that, that’s not my style, but I just thought, let’s piss about and try that. Slow, "word … word … word…", with no explanation. I developed it as we was going along – I thought, ok, I can’t just say words, it’ll sound smarter if I explain what this word means by the end.

So we got to the end, and it was just laughs, jokes. I took it on a CD, and a couple of days after that I got a lift from Jammer to the airport, and I left the CD in his car by accident. I got to Cyprus and panicked, thinking ‘Shit!’ ‘Cause that’s new music, you don’t just let that loose. So I phoned him, I said, ‘Oi, you’ve got that CD in your car’. And he was like ‘Yep, and I’ve heard it’, and he’s dying on the phone laughing, saying ‘You’ve fuckin’ made a smasher!’ I’m like ‘Oh please, whatever man’.

So amongst my peers, it was like yeah, this is the one. And then Kevin got it mixed down and he gave it to Mala, Coki, these dubstep dons who I’d never heard of. He was phoning me saying ‘It went off in this rave, it went off in that rave, we need to revocal it’. So Killa P didn’t do his part again, but I did my part again, cleaned it up, and yeah – dancefloor smasher! [laughs] It was such an easy formula. And that’s what I call the Fat Mac 90. That flow I’m using on ‘Skeng’ was called the Fat Mac 90 flow – don’t use it too often! It came out again on ‘Fat Mac’ and a couple of other tracks.

Your EP is called Serious Business, which sums up the atmosphere quite nicely, really. It also seems to sum up the fact that you seem to be quite drawn to that sort of really intense, dark atmosphere…

F: It’s natural, it’s where I thrive best, it’s what I like. I probably need to speak to a professional about that [laughs] because I just gravitate to that. I like attitude, and the word ‘attitude’ can resonate in so many ways – light, dark, grey – but I just like rudeness. People are drawn to that – like you said, ‘Skeng’ still gets played today in your office, and I bet you’re all lovely people! That’s my point – you all like rudeness. We all do. That darkness, I like to tamper with it, and because I’m in a place where I can express it – legally, and it’s fine! – I just revel in that, you know? I’m always drawn to the ‘bad boy-ness’ of music. I can’t explain why I’m drawn to that energy, but I know that’s where I thrive.

Are you working on lots of new stuff at the moment?

F: Definitely. For months I didn’t stop. Serious Business just sent me into a mode of making music, and there was only four tracks you got, but I made about 15, so it’s just about trying to find different projects to put them on, because I don’t want that to be wasted, I think that was a good time for me, where I was really letting out a lot of styles and emotions that I haven’t done on a solo platform. I’ve never really gone to work as Flowdan, I’ve always been a group member, Wiley’s mate, feature artist. But I went in, I got a studio, I found a new formula and a new way to work, and I just did loads of music.

You’ve been doing this for a long time now. Do you feel like what you want out of it has been evolving as you’ve gotten older? Do you think you have more perspective on what you’re trying to achieve?

F: Yeah, I’m trying to achieve consistency, you know. I’m trying to achieve the option to be able to do what I want, how I want. It’s really strenuous to have pressure and deadlines, and if it doesn’t work, you’re fucked. It’s really good to not have that, but to still have the love for making the music. Once the pressure is gone, you can really express with no limits. That’s what I want to achieve. I want to earn the right to be able to do that, I don’t want to just be given that, I want to spend as much time working on my craft. I do feel that I could do music until I can’t speak – physically, I can do it. Performing will be another task [chuckles], especially how I perform, but at the same time I feel I can do this for ages. I look up to artists right now that have been doing it before me and still are doing it.

I guess you’re around people like Daddy Freddy…

F: Ohhhh my God! He wants to do an encore, every show! Fucking hell! Uncle Freddy wants to do an encore, and that just amazes me. Obviously I’m from a different thing from him, because he’s used to three hour shows, toasting, microphone, ‘hold that’, grab a beer, hold that, go toilet, come back… Where I’m trying to structure it to an intense hour, 45 minutes, and you don’t see me again for the night. I’m trying to have that, cos I’ve still got the Jay-Z in me. [He’s from this] ‘Come, chill, I’ll MC on the dancefloor’, where I want a stage. I want a spotlight, I want to perform.

Flowdan’s Serious Business EP is out now via Hyperdub, and The Bug’s Angels & Devils album featuring Flowdan is out this week on Ninja Tune