"George Clinton and Kraftwerk stuck in an elevator," was the flamboyant image conjured by Detroit musical innovator Derrick May when asked to define his hi-tech new electronic funk music, techno. The 1980s nascent Detroit scene, which revolved around May and his friends Juan Atkins and Kevin Saunderson, was just as conspicuously shaped by Parliament and Funkadelic as it was by the more motorised Yellow Magic Orchestra, Giorgio Moroder and Kraftwerk.

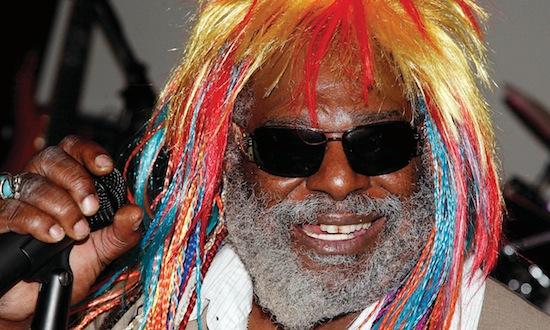

In an otherwise chilled crowd of electronic music industry players at the IMS in Ibiza, where George Clinton is a keynote interviewee, a video of ‘Give Up The Funk (Tear The Roof Off The Sucker)’ has everyone getting loose in their seats. It’s a good introduction to one of the most sampled artists of all time. Bernie Worrell, who is in the spirited audience – having played a jam with George Clinton, Nona Hendryx and others at Nile Rodgers’ Legends dinner on the island the previous evening – is given a massive big up from George for his influence on the sound of Funkadelic, and Clinton also makes sure to namecheck Maceo Parker, Bootsy Collins and Fred Wesley, without whom, he acknowledges, he wouldn’t have achieved his status as purveyor of probably the best funk saturnalias (and albums) of all time.

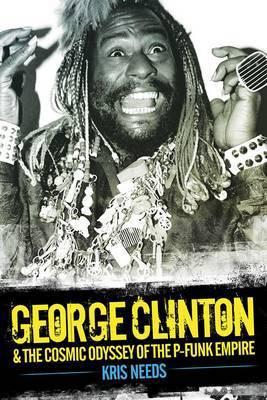

Born in Kannapolis, North Carolina, Clinton was a member of a doo-wop group in the 1950s called The Parliaments, alongside a job straightening hair in a barber’s salon. He went on to become one of the very few artists who could claim complete credibility in the worlds of psychedelic rock and live funk, as well as his vision being a key influence on techno. His (Afro)futurist outlook led him to buy a spaceship – The Mothership – one version of which now resides in The Smithsonian.

But back to that ubiquitous Derrick May quote. Every time I see it coughed out, in article after article, I always wonder how it sits with him. The funkiest American black guy trapped with (supposedly) the most orderly and Teutonic white guys in one elevator? Sitting with him at the pool in the afternoon seems an ideal opportunity to ask.

"Oh yeah! I can dig that," Clinton exclaims. "You know when Kraftwerk first came out they used to play them on US R&B stations, and it actually got real big, which was a surprise. We didn’t know what it was.

"But then later on I worked with Thomas Dolby and I got a pretty good education in what was going to be happening in music, what the future was," he continues. "That was the beginning of techno. We could see then that the whole thing of computerised electronic music was the new future. We’d even heard about it by the late 60s and early 70s – that synthesisers were going to be taking over. With Thomas Dolby we’d be working with the Mirage synthesiser, and it was when I got with him that I saw exactly what was meant, and he knew how to do all the right sounds for that music.

"So when they say Kraftwerk and Funkadelic getting together, well yeah, it works – maybe just because we’re at the other end of the spectrum from Kraftwerk. Like, even at this late date, after all this time, we can still do what the Grateful Dead used to do and just play a basic jam for hours at a show. Now we intend to make a jam band out of electronics, so we have a lot of kids in the band today, and they all got their computers, and their holograms and their electronic music things. A brave new world is here."

The IMS is as bristling with industry people and record company execs as it is with DJs, producers and some of the more underground participants in the electronic dance music scene. To some extent it’s a microcosm of what goes on behind the scenes in Ibiza’s clubland, which is now in its opening week. As such each evening sees a handful of promotional parties and club openings, and by stepping out to a few of them – including the Space Opening Party, from which many Ibiza locals believe you can take the temperature of the entire coming season by seeing who dominates the vibe – as well as glancing at the season’s club calendars for line-ups it’s easy enough to see how Ibiza 2014 is taking shape. It’s notable that both Cocoon (at Amnesia) opening and DC10’s stupendous Circoloco opening party still eclipse the Ushuaia/Avicii axis in terms of local credibility; the island is becoming more polarised than ever, with the techno and deep house scene remaining true to its dance ethos, while the other wing of clubland – the Miami/Vegas-driven Platja d’en Bossa beach bar scene, which often goes hand in hand with Pacha and nights like Guetta’s F*** Me I’m Famous! is often unashamedly about greenback, and being seen.

George Clinton, meanwhile, has been doing his own tour of the island, armed with his own funk barometer. Aside from his presence at Rodgers’ Legends dinner and his keynote interview at the IMS, he’s been to see some of the more mythos-soaked corners of the island, such as the Atlantis beach and the mesmerising leviathan that is the huge rock of Es Vedra (rumoured to be uninhabitable due to its magnetic forces). The latter, allegedly the home of the sirens encountered by Odysseus in the Homer epic, was the inspiration for Martin Sharp’s ‘Tales Of Brave Ulysses’, the song he gave to Eric Clapton and Cream.

According to Clinton, hearing Cream changed his life and gave him a whole new musical direction. On hearing their lyrics, with talk of gods and myths and superheroes, he embarked on what was to become the Mothership era of Funkadelic, adopting Starchild and Sir Nose as his own mythological characters. Beyond that, Cream were the first band to draw Clinton’s attention to Robert Johnson and, to a certain extent, traditional blues…

"Oh my god, yes," he says. "They played the kind of music that my mother played all the time. What got me the most was that I then found out about Robert Johnson from them. I never even knew who he was, and I’m the black guy! Cream taught me all about that. I knew of Robert Johnson’s songs, but not about him and his life. The reason for this [was that] it was all the kind of music that the older folks, like my mother and everyone, used to listen to, and kids don’t like listening to their parents’ music. I know we were one of the first lot to start listening to our parents’ music and enjoy it, and that was because of Cream. Nowadays kids listen to their big brothers’ and sisters’ music, their parents’ music too, but in the past it was a different thing.

"When I heard Eric Clapton explaining who Robert Johnson was? I felt like shit for not knowing this stuff already. He gave him all this praise. I felt like that was one of the reasons that Cream were so successful as a rock & roll band too, because they respected the blues and they respected jazz – they respected grown-up music. I’m from the doo-wop era but them, they knew everything. And that’s what gave those guys the edge on everybody else. I mean, Cream brought blues back into the realms of it all, and so much so that most black kids think that rhythm & blues is white music, and then the radio stations started treating them like that too – ‘You’re black so you can’t do blues and you can’t do rock & roll’, that’s how it was.

"When we started doing Funkadelic we were too black for white folks and too white for black folks," he recalls. "But the fans that liked us and they stayed close to us, and that’s always been the trip all these years, because they still stay with us even now, and meanwhile it just keeps getting bigger and bigger for us. But yeah, after that period, I think it was in the 70s anyway that we really caught on, with The Mothership arriving, and that was a whole ‘nother thing."

The illustrious Mothership, with its vast plumes of dry ice and hail of kaleidoscope lights, out of which Clinton would emerge after it landed on stage, was one of the most entrancingly unhinged stage props ever used by a band. First appearing on the Earth Tour – which started in 1976 – the Mothership’s advent marked the psychedelic party people pinnacle of Funkadelic’s career. Funk deliverance was its message, and it became a vital part of the P-Funk mythology. Despite my strongest efforts, Clinton just laughs and smiles judiciously when I try to ask him what’s actually inside the Mothership. "Well, that’s a secret, but there is a lot of electricity in there."

As well as by then sporting diapers and bedsheets, among many other great and highly colourful forms of clobber, P-Funk were effectively their own counterculture. They’d also absorbed some of the more political energy of people like the Last Poets, and the MC5, whom they’d shared bills with in Detroit, and combined this with their unique brand of cosmically-enhanced funkology.

Clinton’s advocacy of countercultural issues abides today, and one of the things he’s still most cynical about as we talk is the war on drugs, and the co-opting of every underground movement by authorities with access to and control of substances. This, he believes, started at the end of the 60s. "That period changed things for everybody," he states. "To me, Woodstock was the end of that whole era. It was the end of everything as it should have been because it all became so commercial. Drugs even became commercial – watch out for the brown acid! Because before that it wasn’t like that at all. Acid was just coming straight out from the colleges and things were all pretty much straightforward for everyone back then.

"But after Woodstock you had strychnine, PCP and everything that kind of got you fuzzy in the head. So that, for me, was the end of all that period of peace and love. Well, the peace part the kids still believed in, but the system took it all over and co-opted it. All those drugs that you see on television, strange sorts of drugs, and they always have to give you warnings on them, but they are all aimed at whatever the kids are doing on the streets, what’s going down with the kids at any time.

"And they were trying to make it look bad back then, sure, and there is a certain attraction to the word ‘No’, so kids want to do it when you say don’t do it. Obviously they just want to know what all that’s about, because that’s what intelligence is – and that’s how the bad stuff gets in."

This time last year, at the same event, I interviewed Nile Rodgers for the Quietus, and one of the things that struck me the most while talking to him was his ongoing concern about the still limited opportunities in the US for black musicians. I ask Clinton what he thinks about this from his equally skyscraping vantage point. "Well, there are a lot of different opportunities, but it’s real hard to take advantage of them," he replies. "It’s always been hard for any black musicians to do a lot of anything over the years. I mean, if they do make it through they get paid and everything, but probably still not what they’re worth, or for the amount they’re doing. Although Dr. Dre just became a billionaire. But as far as recognition is concerned, it seems the record companies don’t pay nobody. We’re just right at the bottom of all that.

"And right now electronic music is taking over, and downloads are taking over, and that means the record companies are in trouble. So that means black musicians are still in trouble, sure. It means they have to keep finding the opportunities to play. But even with the new electronic music they still need to cop the samples."

Dr. Dre was one of the innovators of the genre known as G-Funk, taking its name from P-Funk, and which used untold quantities of P-Funk samples. Meanwhile Clinton has been deeply embroiled in multiple lawsuits attempting to get him due recompense for all the unpaid-for samples that have been used over the years – though, as he points out, the artists using the samples have paid for them, but the money never seems to move from the record companies receiving it along to the originating artists. He’s also fighting Westbound for rights on his back catalogue, and he’s in another dispute with Warner Brothers.

Apart from his relentless touring schedule, Clinton has helped set up Flashlight2013, a site dedicated to the cause of reclaiming unpaid copyrights from various record companies. To this end he’s also preparing a memoir for publication which will document some of these struggles, as will the reality TV show he’s currently working on with his family, to be called… The Clintons.

He currently tours with a band numbering 27 people of several generations, and the touring never seems to stop. The next night he’ll be leaving Ibiza and arriving a few hours later in New York to play two gigs in the same night. One of the gigs is with Soul Clap, with whom he’s been collaborating for a while now. Clinton has a new album due out soon, and Soul Clap guest, as does Sly Stone, the man he later that day claims is even funkier than he is.

These days George dresses in ritzy suits and waistcoats. ("This is how I used to dress at school! I’ve got a suit habit") And he’s a businessman with a mission or seven up his sleeve. But beneath the surface the old spirit is eternally about to bust through. "I bought a spaceship because that was my car, and I’m still riding it today, even though I don’t have it any more…"