The Planet Of The Apes series has had a curious longevity. The original 1968 classic was followed by four film sequels released between 1970 and 1973, two short lived television series, various comic book series, bucket-loads of merchandise, the truly atrocious 2001 Tim Burton remake, and a new reboot series beginning with 2011’s surprisingly decent Rise Of The Planet Of The Apes, and continuing with the just released Dawn Of The Planet Of The Apes.

These latest films are about as deliberately paced and character driven as one could hope for when it comes to contemporary Hollywood summer spectacle, but while they present some good ideas, they lack the righteously cynical – at times out right nihilistic – fury of the original film series.

Planet Of The Apes was science fiction, which, like all the best science fiction, was concerned with ideas, and explored those ideas by using the fantastic to refract light back onto the issues of contemporary society. Planet Of The Apes turned a wry eye – filtered through a propulsive and deceptively pulpy lens – towards issues of inequality, the corruption of power, and humanity’s boundless capacity for self destruction. Its critical and box office success, along with Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey released in the same year, helped usher in the downbeat ideas driven sci-fi cinema of the 70s and early 80s.

Of course the vicarious pleasure of seeing talking apes run amok also had something to do with the success of Planet Of The Apes and its sequels. The Planet Of The Apes as an ongoing series helped pave the way for the extensive merchandising and never ending sequel model of Hollywood production. Yet revisiting the originals one finds a vastly different breed of film from the polite franchise-building of today. The Planet Of The Apes sequels are far more daring, far weirder, and far more politically radical than cynical studio cash-ins have any right in being. Barring the dismal final film, they cleverly build on and compliment the original, and ingeniously twist and adapt the initial premise, while somehow becoming ever more politically angry and despondent with each successive entry. Looked at as a whole the series forms an ingenious Möbius strip of a time travel narrative that bleakly addresses the way inequality and oppression fosters conflict, and how intractable and destructive that conflict can be.

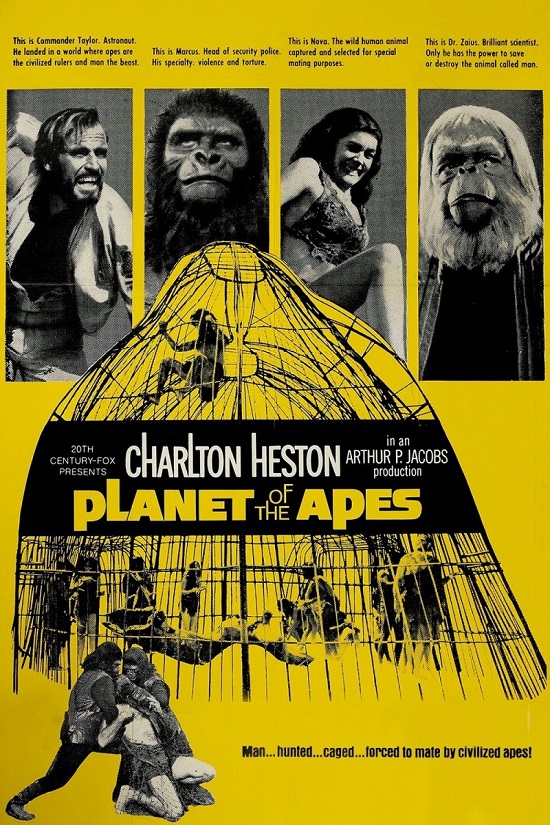

Planet of the Apes (Franklin J. Schaffner, 1968)

The original Planet Of The Apes is one of those films that nearly everyone is aware of through cultural osmosis, without necessarily having experienced it first hand. Much like Rosebud being Kane’s childhood sled, and Darth Vader being Luke’s father, everyone knows about that twist ending. It was earth all along, those damn maniacs blew it up! And Charlton Heston is quite rightly really pissed off about it all. But Planet Of The Apes is more than just the ending. The moral greyness of its characters, the ample ironic foreshadowing, and the way the film is free-wheeling enough with the ape metaphor to cover more ground than just “nuclear war is bad”, means that this twist heavy film richly merits its sci-fi classic status, and more than stands up to repeat viewings.

The film was adapted from a 1963 novel written by French novelist Pierre Boulle, acclaimed for writing The Bridge On The River Kwai. Rod Serling, the man behind the seminal sci-fi television anthology The Twilight Zone, wrote the first draft of the screenplay and was the man responsible for contributing the devastatingly ironic and destined to become iconic ending. Serling’s script featured a modern high technology Ape society like that in the Boulle novel, but this was changed to a more primitive society largely for budgetary reasons. Yet this added to the concept; as the ape society’s technologically primitive, yet highly bureaucratic and religious nature suggested all sorts of intriguing subtext.

Screenwriter Michael Wilson further worked on Serling’s screenplay, and added much of the sardonic anger found in the finished film. Wilson was blacklisted in Hollywood for his communism during the McCarthy era, and did much work uncredited in the 50’s, including clandestinely writing the Oscar winning screenplay of David Lean’s adaptation of Bridge On The River Kwai for which Pierre Boulle was instead given the best screenplay Oscar despite freely admitting to not speaking a word of English. The anger of the kangaroo court scene in Planet Of The Apes in particular reflects Wilson’s first hand experience of McCarthyism.

The film begins with Heston’s misanthropic astronaut Taylor crash landing on a seemingly unknown planet. After an extended mood-setting intro Taylor discovers savage mute humans, and is almost immediately captured by sentient, gun wielding gorillas. Franklin J Schaffner’s masterful direction, Jerry Goldsmiths’ radically atonal score, and John Chambers’ brilliant ape make up, all combine to make the ape reveal a dizzying Boschian nightmare that’s lost none of its power, as opposed to the goofy camp it so easily could have been.

Taylor spends most of the film imprisoned as he struggles to prove his sentience to the rigidly demarcated, highly religious, corrupt ape society. Eventually Taylor escapes with the help of sympathetic chimpanzee intellectuals Cornelius and Zira (played by Roddy McDowall and Kim Hunter). After a final confrontation with the ape leaders, Taylor stumbles upon a half destroyed Statue of Liberty, and his new found pride in his humanity is utterly shattered.

It’s an incredibly bleak gut punch of an ending. The hero loses, humanity has destroyed itself, and that which has taken its place is no better. It perfectly tapped into the tumultuous uncertainty of 1968. Similarly pulpy but ideas driven sci-fi like Star Trek saw the troubled world of the 60’s and boldly proclaimed that it was all just a blip in the flow of liberal progress. Planet Of The Apes conversely, and in a deceptively entertaining manner, looked at that same world and declared that if we don’t get our shit together than that’s it; there’s no coming back from some things. In subsequent Apes films the outlook would only get darker.

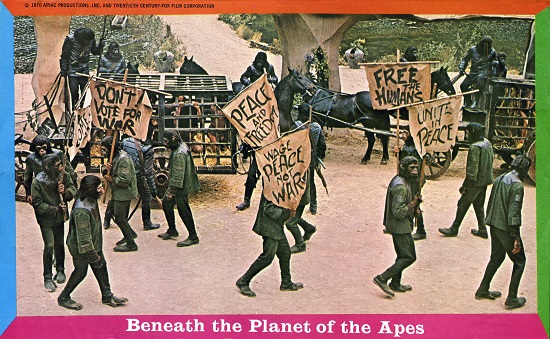

Beneath the Planet of the Apes (Ted Post, 1970)

Beneath The Planet Of The Apes is not a “good” film, by any conventional metric, but it’s totally batshit insane, and pacey enough to never risk becoming dull. Its ludicrously nihilistic finale makes the whole campy mess hang together in its own weird way. The first film is legitimately great, but Beneath The Planet Of The Apes works brilliantly as demented shlock; plus its bizarre plot turns helped push the series as a whole into ingenious new directions.

Planet Of The Apes was a huge hit, and the studio wanted a sequel. The original was envisioned as a stand alone film, and sequels were far from a foregone conclusion at the time; the James Bond series being about the only other lucrative high profile multi-film series around in the late 60’s. Yet the prospect of all that ape money beckoned.

Pierre Boulle and Rod Serling were approached to develop scripts for the next film, but their ideas were ultimately rejected. Instead Paul Dehn was contracted to write the next instalment, and he would go on to write nearly all of the subsequent sequels. Dehn was a British film critic, turned war time spy, turned poet, turned successful screenwriter; a renaissance man to say the least.

His script was hampered by both a reduced budget, and by Charlton Heston’s initial refusal to appear in the film. The producers and director Ted Post were adamant at the necessity of Heston’s involvement, so a rather awkward compromise was arrived at. Heston would appear in the film for only fifteen minutes.

Heston’s Taylor literally disappears into thin air in the first act, and is replaced by James Franciscus’s Brent. Brent is a thinly drawn new astronaut on an implausible rescue mission to save Taylor. Brent quickly teams up with the returning impossibly glamorous barbarian woman Nova (again played by Linda Harrison, who does great work with a truly thankless role).

The first half of the film more or less repeats the same beats as the first, with Nova and Brent getting captured by apes, and subsequently escaping with the help of Zira and Cornelius. It’s pacey enough to retain interest, but over-familiar. Thankfully the insanity soon begins to ramp up. The protagonists stumble upon the underground ruins of New York City, where they encounter intelligent human survivors. Yet these survivors are telepathic mutants who worship a giant nuclear bomb as a god, and pray to the “holy fallout” in the alter they’ve constructed around the weapon. It’s lurid and totally bonkers, yet also effectively unsettling.

Things culminate with an apocalyptic conflict between the increasingly militant apes and the mutants. It initially works as a coarse Vietnam metaphor (that includes protesting anti-war chimps getting knocked around by black shirted gorillas) but it quickly takes an excessive turn. Brent is reunited with Taylor, and in the process Nova is accidentally killed. The apes enter the mutant underground and begin slaughtering all they find. Brent dies a horrible bloody death, Taylor is mortally wounded, and with his dying breath activates the mutant’s nuclear bomb, seemingly out of pure misanthropic spite. The screen flashes white, and a narrator coldly states: “In one of the countless billions of galaxies in the universe lies a medium sized star, and one of its satellites, a green and insignificant planet, is now dead”.

Thus ends a film marketed as family friendly light entertainment. It’s an incredibly ballsy ending, indeed outright nihilistic in its despondency, and it essentially re-frames Heston’s character as the villain of the series to date. He’s the harbinger of the apocalypse, and in hindsight the apes were not unjustified in giving him such a hard time. Humanity is inherently, and unavoidably destined to destroy the planet, and there is no hope of salvation. It’s an incredibly dark sentiment for a film to convey, let alone a family friendly action adventure.

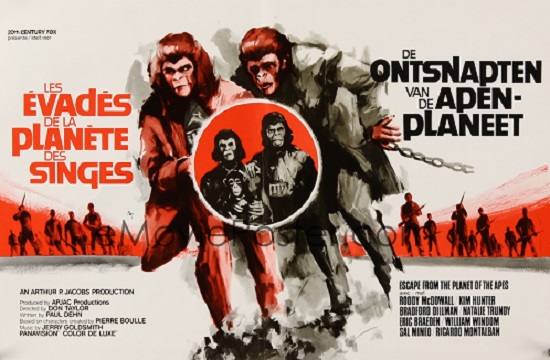

Escape from the Planet of the Apes (Don Taylor, 1971)

Once you’ve killed everyone, and literally blown up the central premise, there is seemingly nowhere else to go with a story. Beneath The Planet Of The Apes was initially intended to be the only sequel, but it was surprisingly successful financially, if less so critically, so of course another film was needed. Paul Dehn allegedly received a telegram from producer Arthur P. Jacobs that simply stated: “Apes exist, Sequel Required”.

His solution was an ingenious one. The premise of the first film is reversed, and the audience sympathy is shifted to lone apes now lost in a harsh human world. Returning apes Zira and Cornelius – again played by Roddy McDowall and Kim Hunter – escape the destruction of future Earth in the repaired spaceship of Taylor, and are hurled back in time to the 1970s. The plausibility of this can be nitpicked, but when dealing with time travelling talking chimps it’s perhaps best just to roll with the hazier details.

Their ship crash lands on present day Earth , and the US government is stunned to find apes in space gear exiting the ship. They initially attempt to play dumb, but quickly reveal their sentience, while keeping the bleaker truths of Earth’s future to themselves. This charming talking ape couple gain instant celebrity status, and what immediately follows is a pleasingly frivolous light comedy that gently skewers elements of 70s society.

Yet things organically take a turn towards the dark and tragic. Zira admits that she’s pregnant, and Dr. Hasslein (cooly played by Eric Braeden) a science adviser to the US President, begins to suspect that there is more to the apes’ tale. He eventually coerces the truth out of Zira, and learns that apes will one day dominate mankind, and that the Earth is destined to be destroyed. Hasslein decides that the only way to save mankind is to destroy the apes and their soon to be born child. The likeable Cornelius and Zira flee the authorities, and are pursued to their hiding spot in a derelict boat. In a horrifically grim finale, Hasslein guns down Zira and her new born child, and Cornelius is shot dead by snipers while trying to protect his family. Zira throws her dead child overboard before crawling to her husband’s corpse and expiring. The final scene sets up the next film, as it’s revealed that Zira and Cornelius’s child was switched with another chimp, and is now in the care of a kindly circus master played by the one and only Ricardo Montalban.

Another ‘family friendly’ Planet Of The Apes film, and another shockingly brutal and bleak ending. Indeed Escape From The Planet Of The Apes may be the most viscerally upsetting of the series, and its tragedy is only heightened by its initially light-hearted tone. The miserableness of it all is only complicated by the sophistication of Hasslein’s motivations. The ostensible villain at one point laments “Later we’ll do something about the pollution! Later we’ll do something about the population exploding! Later we’ll do something about the nuclear war! You act as if we have all the time in the world. How much time has the world got?! Somebody has to begin to care.”

It’s hardly the words of a moustache twirling monster, and just about any politically sane individual would agree with his sentiments today, yet his desire to save humanity compels him to gun down a mother and her child. It’s a disturbing example of the ugliness of utilitarianism. On a more abstract level it suggests that the continued dominance of one group over another is predicated on brutal acts of violence and oppression; brutality that will eventually in turn lead to violent retribution from the downtrodden.

Conquest of the Planet of the Apes (J. Lee Thompson, 1972)

Escape was just financially successful enough for another sequel to be put into production. Each film had a progressively smaller and smaller budget – the series was a cash cow to be wrung dry in as financially efficient a manner as possible. It’s a stark contrast with the near limitless budgets of the too-big-to-fail franchise monstrosities of today.

1972’s Conquest Of The Planet Of The Apes was the cheapest Apes film to date, but also the most radical in its politics. It’s hard to fathom how it even exists, but apparently the producers were blissfully uninterested in the content of these talking monkey pictures as long as they remained low cost/high return. A thin veneer of sci-fi allowed the most radical and difficult of ideas to fly in under the radar.

Conquest deals with the necessity for the oppressed to rise up in violent revolution, and it offers few caveats in response. America is now the near future dystopia of the 1990s. Cat’s and dogs were wiped out by a plague, and mankind in their sadness replaced their beloved pets with domesticated monkeys. They quickly realized their intelligence and ability, and apes soon became the slave labor of humankind.

It’s a slightly goofy explanation for ape enslavement, but it more or less works if you’re willing to meet it halfway. Roddy McDowall returns, now playing Zira and Cornelius’s son Caesar, who has grown up in the loving care of Montalban’s kindly circus owner. The black leather clad quasi-fascist authorities begin to suspect that Caesar is the hyper intelligent offspring of the future apes. He’s forced into hiding amongst the slave population, while Montalban is captured by the authorities and ultimately killed while protecting Caesar’s secret.

Montalban’s death, and the harshness of the apes’ treatment, causes the initially timid and gentle Caesar to radicalize and organize an ape revolution. Weapons are stockpiled, minor acts of sabotage are carried out, and it eventually escalates into an all out bloody street war, as the apes rebel against their masters.

Yet the film comes across as more or less totally in favour of the revolt. The humans are all deeply unsympathetic save the martyred Montalban, and the apes suffer in viscerally cruel ways at their hands. The visual harshness of the unnamed future city only further accentuates the rottenness of human society. The at the time new and bleakly modernist Century City development in Los Angeles made for a cheaply filmed but visually striking future dystopia.

It works as pure Marxist allegory, while also tapping into and playing off of audience memory of the race riots and urban unrest of the then recent past. Indeed director J. Lee Thompson was inspired by imagery from the 1965 Watts riots. Test audiences reacted negatively and the studio belatedly realized just what they had produced. They’d finally made an Apes film too brutal to be marketed to families.

The violence was toned down for the theatrical release and the ending altered. In the director’s cut (now restored and available on blu-ray) the film ends with Caesar making a speech on the supremacy of the apes before his followers bludgeon the human leader to death, with Caesar looking on silently as the city around him burns. In the the theatrical cut the violence and gore is toned down throughout, and Caesar strikes a conciliatory tone in his final speech and calls for the need to show mercy to the defeated humans. If anything the theatrical cut inadvertently makes the film more radical, as it whitewashes the unsettling brutality of the revolution, making the prospect of armed revolt seem even more benign a necessity.

Either version of the film is well worth tracking down, and it may be the most politically angry and incendiary call to rebellion in cinema this side of Battleship Potemkin. Looked at as a whole the Apes series to this point paints an overarching narrative where harsh oppression leads to justified violent reaction, which in turn inadvertently leads to new forms of oppression and new conflict, in a cycle that ends in the definitive destruction of all life. It’s as bleak a message as possible, but a powerful one, and the Apes series could have easily ended here. Unfortunately there was to be one more film.

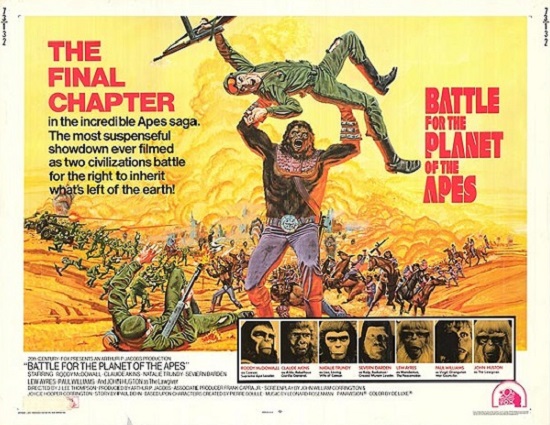

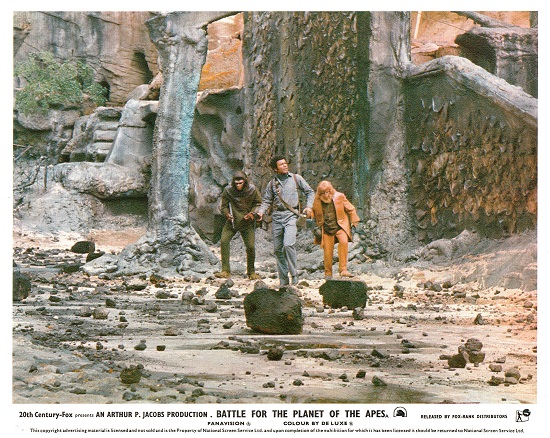

Battle for the Planet of the Apes (J. Lee Thompson, 1973)

Battle For The Planet Of The Apes is easily the weakest of the original films; partly because the budget had finally been slashed to a point of no return, and largely because it’s story is superfluous and poorly told. After four increasingly bleak films, and the particularly brutal fourth instalment, the studio finally decided to make a Planet Of The Apes film actually tailored to children.

Paul Dehn wrote an initial draft with Caesar as a harsh authoritarian leader in a post-revolutionary society, who is eventually killed by his subordinates when he softens his stance towards humans. Needless to say the newly attentive studio wasn’t happy with this tale of a Malcolm X like ape revolutionary. Due to health complications Dehn ceased to work on the script, and was replaced by John and Joyce Corrington, who had previously written the post apocalyptic Charlton Heston helmed film The Omega Man.

Roddy Mcdowall again returns as Caesar. Nuclear war has occurred in the interim between the films, but Caesar and a band of other, now talking, apes live in the wilderness in unison with friendly but subordinate humans. Eventually Caesar stumbles upon mutant humans in the ruins of a human city, sparking a war, while all the while dealing with gorilla usurpers challenging his rule at home.

The plot is essentially a more restrained, child friendly, repeat of the conflict in Beneath The Planet Of The Apes, but the real issue lays in its execution. J.Lee Thompson returned to direct, but this time was unable to overcome the limitations of a miniscule budget. Battle is an ugly, flat, beige film. The clashing ape and mutant armies feel more like skirmishes between street gangs, and there isn’t enough dynamic weirdness to overcome the cheapness of the production.

It’s also awkwardly paced and structured, with an excruciatingly slow build up, and lots of time wasting that seems designed just to get the running time up to the appropriate hour and a half length. At times it feels like the pilot to an unimpressive TV show, and there are lots of slow and shallow discussions on what makes a just society that recall the most dire of the early Star Trek: The Next Generation episodes.

Battle attempts to suggest that apes and humans can finally be reconciled and avoid an apocalyptic future. Allowing for reconciliation to be the ending of this long running and continuously pessimistic series is admirable, but the film is so poorly constructed that it’s all rendered moot and ultimately a bit laughable. One terrible film out of five is still an excellent average, and as rote and dull as Battle is, it still surpasses the god awful Tim Burton Planet Of The Apes remake.

The original Planet Of The Apes series is in many ways a curious anomaly that could have only existed in its unique moment in time. These were highly commercial genre films that existed in an age when cinematic sci-fi could be more than empty spectacle, and could tackle the biggest questions haunting humanity. A time when Hollywood films could be despondently pessimistic about the world, without being cheaply exploitive in their darkness. As long as there is still inequality and division at hand these thrilling, pulpy, sometimes ramshackle, ideas driven films will continue to resonate. That and the sight of a gun toting talking ape never exactly gets old, does it?