It’s a funny thing, to read a book set where you grew up. Particularly when it is so uncannily placed, street names and all, like Vulgar Things, Lee Rourke’s second novel. The book’s protagonist is Jon Michaels, a man who to whom, it seems, everything has already happened. An editor who has just been sacked from his London job, affected by childhood trauma, and the more recent trauma of his Uncle Rey committing suicide. This man in crisis is drawn to Southend and Canvey Island: a place full of light and sky and sky and mud, a place where cartoon machismo abounds.

Rourke lives a few minutes north of Southend’s seafront-ensconced dive bars and amusement arcades, and the shady strip clubs on Lucy Road. He cheerfully welcomes me in with a handshake and an offer of coffee. His house, which he shares with his Southend-born wife Holly and his baby daughter Thea, sits in what when I was growing up was an undesirable part of the town, hugging the Red Light District while its inhabitants hugged the smack. His road is a minute from Toledo Road, a key location in Vulgar Things: from this street Jon overlooks Queensway, the old river of Southend, from a grass bank that holds a cherry tree. Something horrendous occurs on Toledo Road, but something that is also everyday.

There is a very real darkness in this novel, a darkness that comes from the male gaze, and its unquestioned, unparalleled dominance. A gaze that makes its way into hitherto innocent pursuits: romantic, idealistic – a similar impulse that brought many to Essex in the first place. To me, the novel implicitly talks of this migration, and Canvey Island seems an uncanny setting for the character of Uncle Rey, whose death sets the story in motion. Canvey was once a place that lured men from east London with the promise of paradise, but ended up with a dark reputation, not least among its own inhabitants. On more than one occasion when I have asked the best way to get to the other side of Canvey from its edges at Benfleet Station, I get an answer invariably along the lines of: “I wouldn’t fucking bother if I were you!”

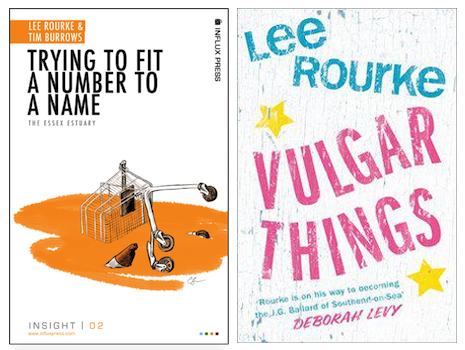

But there is a real beauty in Thames Estuary Essex, which belies media myth and TOWIE. Rourke and I are writing an essay each for an E-book on the area for Influx Press, entitled Trying to Fit a Number to a Name. The joint effort will be out September time and is named after a line from 1970s razor-sharp Canvey blues group Dr Feelgood’s ‘Sneakin Suspicion’. It seemed to describe the way we were both trying to work out Thames Estuary Essex in our own ways: he a Mancunian finding himself in Southend via Hackney and Walthamstow in east London. Me in Walthamstow, via Hackney and Cornwall, more than ten years estranged from my hometown of Southend at the end of the Thames but drawn back again and again.

The director Julien Temple juxtaposed the Dr Feelgood story with British bank robbing capers and American gangster films in his 2010 documentary Oil City Confidential to feed the myth of these outlaw bluesmen from Canvey. In Rourke’s book, those same images are treated by a more European cinematic influence. “I wanted each fragment and each chapter to be a framed picture of things that are happening, which goes back to when I first travelled to Southend on the train and saw the estuary through the frame of the window of the train carriage,” he says as we sip a black brew in his loft. “The window of the train carriage acted as a frame, and it was just this beautiful scene of the Estuary: the tide was out and there was all the mud. It really felt like La Jetée by Chris Marker, which is a feeling I tried to inject into the book, this series of separate but corresponding images.” Down By the Jetty becomes Down By La Jetée; the black-and-white still images of a sleep-deprived Wilko Johnson, Lee Brilleaux and Doctor Feelgood glaring out of their debut record transform into Chris Marker off-cuts, too grotesque even for post-apocalyptic Paris.

The way you describe Southend is interesting – there is a real repetition to a lot of it, like the container ships that keep appearing, which actually made me feel like I was there. I thought about it as I have been walking around here over the weekend: walking around Leigh, going up the hill, going to Westcliff, and seeing the same scene of the estuary come back into view again and again, like a weird repetitive film loop. It really feels like the place. Did the book just come out of the place itself?

Completely out of the place. It’s funny how you talk about loops and recurring imagery, and images especially, and sounds, and places, and things. I think it’s a natural response in me to the natural ebb and flow of the estuary – that kind of constant in and out throughout the day. And I think everything in the novel reflects that. The wanderings Jon does, it’s a backwards and forwards movement, along the estuary into Southend, back to Canvey, into Southend, back into Canvey. Along those routes there is the recurring imagery and certain things repeat – Southend Pier, and the container ships, which are a kind of ebb and flow of data, moving along the estuary. I had no idea what I was going to write about plot-wise – I don’t write like that – but I knew as soon as I went on to Canvey, and I just thought this is the strangest place I have ever been to. It is so near yet so dislocated from everything. The flatness of it; the eye sees the sea above the land by the Labworth Café, so that idea that it is below sea level, there is a real psychological thing going on there. And the fact that there was a flood and that has happened, and the people on Canvey talk about things pre-flood and post-flood, so there is an almost… Wilko Johnson calls it a “biblical edge” to the place. There is this real sense of catastrophe. I just knew that all that kind of trauma and repetitive motion is food and drink for the stuff I want to put in books, so I just went from that. I knew it had to be about the estuary, it had to be about Canvey and it had to be about Southend.Also, a stylistic thing that is crucial to the book is that it is purposely flat, like the Estuary itself. It is really flat and unreflective prose, which was inspired by the opening of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness: “the low shores that ran out to sea in vanishing flatness”.

Did you find it difficult to describe the place? Nikolaus Pevsner, the architectural writer, came here. He couldn’t really get to grips with it – it was almost too much for him to articulate what was happening. He really latched on to things like Coryton Oil Refinery. He said in the introduction to his book on Essex that the county is a hard place to describe and that chimes with what you seem to be doing – almost trying to write it into being.

For me, topographically it’s kind of beautiful and architecturally it is patchy and ugly, but there are moments of beauty within the architecture. What there is a sense of is ancient pathways up and along the estuary: where I live just down the road is the old Southend Road, which is the original dirt track from Prittlewell down to the ‘South End’ of Prittlewell, to the beach. And that still exists, a trace of old Essex. If you go down to Old Leigh you still get a sense of how things used to be, and it’s still a working place, people still live off the estuary in that way. I guess I wanted to reimagine those ancient trails and ancient forms of mapping which were based on walking: going to the place where you worked and coming back, over time the toil is etched into the land in the form of tracks. I wanted to echo that in a sense of reimagining other, through a reality of things, but not in the sense of wanting to capture the reality in that way, or make that reality a literary thing: I wanted the reality of Southend to be the thing itself in the novel.

I kind of did that through observation in the present tense, and also through listening. It is a novel about watching and listening: he watches everything but he can’t really think about that because he is constantly in the present, constantly moving. So all he can do is record. There is a lot of recording in the novel. And he himself is a kind of node that records for us, in the way that we would walk down the street and then the recurring patterns and images would filter in that way.

It feels like we are kind of plugged into his brain somehow.

Yeah, in that way – he’s the eye for that reimagining. For me as a writer I didn’t want to sit there with an Ordnance Survey Map, and map everything. In fact the map I used to reimagine Canvey was the pirate map made by [Dr Feelgood singer] Lee Brilleaux when he was a kid, reimagining Canvey itself. It’s a really weird thing; Ballard says you’ve got to create reality from the fictions around you. I don’t know if I’ve done that but I seem to have captured a certain sense of reality by not being realist in my approach to its composition.

It feels so strangely evocative of the place. And so does the dialogue, especially when he is absorbing conversations he has no part in.

He’s drunk a lot of the time as well – he is going through some kind of traumatic event himself. When I’ve been drunk, the world around you is a cacophony; it’s just a series of sounds and voices. It’s kind of what’s happening to him. People are just sliding by, saying something and then moving off frame, and then coming in, saying something to someone else. Then other people may sit next to him and he may hear a little bit of their conversation – and then they go. That’s the world around him for a lot of the time, this endless series of voices. Not in an information overload way like films like Scanner or things like that, where you want to switch it off. He’s constantly listening and wants to listen.

It is almost like he’s taking the instincts that have got him into publishing in the first place, and using them as a kind of coping mechanism.

He’s not happy with the construct of work and he’s not happy with the office environment, but essentially he’s an editor and he feels he’s a good one. He has an intrinsic desire to edit. I think he’s editing the world around him and taking snippets, and putting them together in a collage of events.

He’s really driven by obsession but also by idealism – by the idealised woman in the novel, Laura. That seemed to link to Essex well for me. People ended up on Canvey, on these plotlands, because of this idealism. It was often a very male thing: they uproot their families from the East End and go and live in some tumbledown property in a wilderness.

And it was like that – people used to live in disused railway carriages and things like that. They used to call Canvey the Wild West. Yeah, there is this idealism in him and a particular type of idealism, governed by the male gaze and all the misogyny within that. I don’t think he’s aware that he has fallen into that trap of objectification. But it’s a kind objectification: he doesn’t want to rule and conquer, he wants to connect through that, and the only lens he has is this skewed objectification of the woman: i.e., desire itself. Desire underpins the entire novel. Everyone and everything is governed by this desire for desire.

I think that’s what makes it so compulsively readable. You feel as if you’ve been drawn into this thing – which manifests itself in a real desire to find out what is happening! I know you say you don’t write plot first, but it feels like a detective novel, the pace of it.

All my novels have that element – The Canal has a chase scene, for God’s sake! I have that sort of mind, I like ciphers and I like to work them out and find and look for clues; I am obsessed with those sorts of things, but I don’t set out to include detective tropes. My two favourite things are desire and its mediation, and truth and its mediation, and I worked those into this novel via Petrarch and Virgil. Petrarch, famous for his sonnets about Laura: he saw this woman on a bridge, immediately fell in love with her, never saw her again and spent the rest of his life writing 800 sonnets about her. So you get this Petrarchian idealised image of the woman – this woman up on a pedestal, where love is worship from afar. And it also becomes this kind of dislocation of the real, which is the meeting on the bridge, from the unreal, which is its mediation via sonnets. For anyone who knows their Baudrillard, the simulacrum, the mediation, becomes real. The desire then is in the poetry, not in the actual meeting. Our desires are mediated, they get far removed from the actual point of connection. That’s what I wanted; so that’s why he’s never quite reaching that moment of connection. It’s always the mediation of getting to it.

Another thing I wanted include was this idea of truthfulness in the novel – this idea that we can write the truth: we can’t. Virgil’s writings were all about truth. In The Aenied, Aeneas the True is supposed to be this personification of the true, but those stories were rewritings and reappropriations of Homer; they were also to gain favour with Augustus; to write a very biased history of Rome. There is no truth in it whatsoever. That’s kind of what I tried to feed into the book: no matter what the protagonist sees and what he is trying to feel, and what he is trying to achieve, there is no truthfulness in it, because it can’t be – at the end of the day it’s just a book, it’s not reality. It’s a mediation of desire, of truth, which isn’t truthful, or isn’t desire itself. That’s the thing that I got caught up in, which kind of propelled me backwards and forwards.

I think there is something that lends itself to this kind of philosophical enquiry about the area. I interviewed Iain Sinclair for The Quietus the other day and he tended to agree that the Thames Estuary lends itself to a freedom of thought that is unlike much of the South East.

Definitely. You’ll only know it if you come here; the mediated truth about this area is of a TOWIE, vulgar, showy existence – the mediated Essex myth. That becomes the truth, the mediation of it. When you actually meet Essex head on and come here, you find that it’s not like that and only certain aspects of it are. When you go down to the cockle sheds at Old Leigh you are so far removed from what is happening up on the Broadway, where people are parking up in their Ferraris and talking in numbers and in commodities – you are so far removed but it’s the same place. To me, it’s so beautiful that it is lower down, Old Leigh and those areas, and the arcades of Southend are lower down than the rest of the town. When you investigate them you start to see that there are different narratives in Essex that don’t really get noticed. There’s a real sense of storytelling: you go into the old pubs and men tell stories to each other – there is a real loquaciousness and a real kind of pride in the old traditions as well. And a real distrust of London that I didn’t know existed.

It’s very real, that distrust.

Yes, it’s very real. Me, believing the mediation, I thought that everybody here was from London, that they’re all cockneys, but it’s not true. And if you have a really good ear, you can hear the original Essex accent sometimes: you hear that twang. There are lots of things like that if you spend time here. And then it’s kind of mirrored by when the sea goes out and there is this flatness to it, you start to realise that this part of Essex is a real amphitheatre or canvas where things can be made or where petit dramas can be acted out. It is an arena of narrative, and histories and mythology – lots of mythology here. And lots of old stories: in the book, the lady in the lake is a repeating myth that is in a lot of the literature of the area. It’s in Andromeda by Robert Buchanan, who is a kind of ghost in the novel

Jon ends up running away and taking refuge by his grave, near here. To me it is a trace of the Bloomsbury London writer escaping to this part of the world, which is such a tradition. Tell me about how you found about Buchanan?

I read Andromeda: The Idyll of a River. For a Victorian novel, it’s really good. There is some wonderful writing about the estuary in there, about the creeks, as good – and this is going to sound bold – as Conrad’s opening chapter, with the greyness welding together, in Heart of Darkness, which is mind blowing. There is some wonderful writing about the topography of Canvey, especially of the river, of the mudflats, especially when the sea’s out and you are left with this glistening mud. But also, the thing that really struck me was the disconnect: the sense of being away, the sense of being detached, especially that area where the Lobster Smack pub is. Dickens wrote about the Lobster Smack in Great Expectations. Even now, you go there and you do get a sense of being stuck out in the middle here.

It’s such a weird place: because of the sea wall at Canvey, there is no sea view. It’s in the perfect location for an Essex gastropub where you would have this view, but because it’s on Canvey you can’t – and the great thing is you can still get two meals for a tenner because of that. It’s still a real locals’ pub.

That’s what really sums up Canvey for me, and why it’s such a brilliantly weird place. You have this beautiful Essex weather-boarded pub that has been written about in the literary annals— anywhere else that pub would be a world famous pub because of the views, but because of the way Canvey is, because of the sea wall, it isn’t. And then there are the barbed-wire railings of the caravan park on the other side of the car park. You could be in a car park in north Manchester. But the beauty of it is if you walk up to that sea wall and you see the ghost of Canvey’s short-lived industrial past: the pipe networks everywhere that aren’t used anymore, and things like that from the oil refinery. And then you get this beautiful slope down past the jetty, on to the estuary itself and then the greenness of Kent is almost within spitting distance. That’s what makes Canvey an amazing place: it’s like a pub that’s hidden, it’s snuggled itself in some corner of the world.

What made you make the place a central setting in the book? Was it because of something that you experienced there, or was it that it had been written about?

Two things: it had been written about, it’s important for me that there is a literary haunting there – not that I’m a hauntologist, but I do like to excavate the layers of literature within the literatures I’m writing – and that it just felt such an amazing place when I first went there, and I just loved the fact that you’d walk up to the sea wall and you’d follow the island around by that way. And also the sense that it is so tucked in there by the wall. There is a real sense of catastrophe: the power of nature and the sea is just there above you, and you are sitting there with your beer. And then, not only that, towering above are the colossal container ships that glide by.

Did you make a lot of visits for it?

No, I’ve been there three times. Had a meal there, a few beers. Walked around. I’m not that sort of writer really: I go off memory, instinct and my gut – and if I don’t remember it correctly, for me that’s even better because then I have removed myself from the reality and it becomes a reimagining. If you go there now, it’s not like it is in the novel, which is great because it could never be even if I tried. But I just knew it had to be a central place he returns to in the novel, it’s got to hold it all together.

And the caravan park itself, did you visit that and map it at all?

No, I knew there were a couple of caravan sites there, and just walked passed them and thought “OK, he can live in one of these caravans”. It was perfect, the day I was there, there was a guy outside his caravan mowing the lawn, his little patch of grass, like the proudest man there. I just thought, this is your patch; you’re so disconnected from everything else, here by the sea wall. Everything else that is happening is behind you. I love that idea that there is a certain type of man who can live like that for all their life. They just have their little plot, their little bed, place to live, with all their stuff, and there is no one to tell them what to do with their stuff or where to put it, and they just live out their life like that. There is a pub within walking distance that they can go to and have their pint, and talk about the world and their fears, and then they go back. That’s kind of the man Uncle Rey is. And then that connection with the stars, that’s important, because the skies in this whole area are amazing.

That whole ‘big sky’ fascination goes back so far. There was a writer called Arthur Dent, who The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy character was named after, who was a pre-Pilgrims Progress theologian who preached in Shoeburyness. He was just one of the many God-fearing writers and personalities through the centuries, with a lot of people talking about the sky – you really feel the sense of the sky, weighing down on you.

My wife is from Southend and she says the first time she took my here one of the first things I said was “My God look at the sky”. It’s the nearest thing to the skies I’ve seen in America when we travelled across, to Arizona and places like that, where everywhere you look is just sky and it just seems endless. I feel there’s a real connection. I’ve seen more men with telescopes in this area than I have anywhere else in the country. I’ve got one here in the loft of my house…. It is a motif in the book, this connection with Saturn and this connection with the stars that Rey has. In old literatures, especially in Virgil, there was always a real connection between man and the cosmos. In Vulgar Things, there’s that same sense of that, but there’s a disconnect, and the only time he connects with it is when he records it and replays it, because now life is different. There is a digital reality now that is overlapping everyday reality. Everything is being digitised and replayed back – the greatest example of it is when we used to go to gigs we could bring our lighters that would burn us and it was a collective outpouring of joy and emotion; now you go to a gig and you just see people recording it. And then what becomes real isn’t the moment you put the mobile phone up – the reality is the watching of it on YouTube, the recording of it. That’s what we’re all doing. I was at the Leigh Folk Festival yesterday and people were recording it, taking photographs of things: they’re overlapping their immediate reality with the digitised version of it, which is becoming our reality of the world.

And it just becomes this endless deferral. In the novel, everything feels like it has been somehow deferred through technology. Through Uncle Rey: you can see the move from analogue to digital through him. He reminds me of Beckett’s Krapp, but he bridges the gap from the spools to what we have now.

To digitisation, yeah. He’s completely from Krapp. The same thing runs through it all, and this is what Beckett pinpointed. The same thing that underlies the technological mediation is desire, and all we are searching for is desire. And that is what everything in Uncle Rey’s mediations, from his VHS tapes to the digitised recordings. He is pinpointing that moment when he felt true desire with… I don’t want to give any spoilers away. But that’s what he’s pinpointing; it’s the mediation of it, that’s telling us where desire lies and what desire is in him. That’s where we’re at now, that’s how we see the world. There is a real strange intimacy with the digital reality of the world; we touch it and feel it. We didn’t used to. We used to have photographs behind cellophane and flick through them but now we touch them and enlarge them with our fingertips.

It’s funny. In the essay I wrote for Influx I talk about only experiencing Dr Feelgood through YouTube, and how that still constitutes a thrill, but only a passive one. What Dr Feelgood I think represents for us both is this active, almost violent engagement with the world which feels impossible now – so what we have instead in Vulgar Things is Dr Feelgood on T-shirts, Dr Feelgood playing in this nostalgic setting in the caravan. But the sound that is coming out sounds so vital, as if it is happening now, which is Wilko Johnson’s guitar…

Which I see as the geometry that holds everything together in the book. Wilko Johnson, for me, is a genius. First thing is, I’d heard of Dr Feelgood, I’d heard their music before I moved here and it meant nothing to me. I liked it, I thought yeah bluesy, great. I like to go to pubs, old men’s pubs, I like to sit and listen. And then I started hearing: “Wilko Johnson”. People everywhere, talking about Wilko Johnson. Men, old men, as if he was a god. I realised he was from Dr Feelgood, so I dug out some stuff and I still wasn’t that keen. But over time there was something about the area, and about their music that really fits together. Then I started to get it and then I started to become a real fan. And then I started thinking about what Wilko Johnson did. Now he’s a very literary man, and a wonderful musician – he reinvented the guitar basically – and one thing he and Lee Brilleaux did was to create a myth around them. They grew up with myth, on the estuary, there’s lots of myth and they know how important myth is. What they did was create a myth around them about the area they live in: this idea of the Thames Delta. This idea that people were playing the blues on their doorsteps with this industrial behemoth growing beside them, the oil refinery. Wilko describes it as this Miltonic beast living side by side with their music. But this myth generated to the extent that London journalists came to Canvey expecting every body to be playing skiffle and blues but it wasn’t like that: it was just a beautiful myth.

I went through the same conversion. I’m from here and my Dad’s in a band. During the 90s when I was discovering music, they were so unfashionable. Every band in Southend was based on them, so you’d have all these bad blues bands playing every single pub. I didn’t realise back then that every song was a saga set on Canvey. I just thought they were a bit abstract. Like Wilko’s song ‘Paradise’: “See the big ships go gliding by”, a line that you use in the book.

That was the one about Wilko’s affair. That’s the song I had in mind with the book, and yeah, that lyric is in there. It’s a perfect song. There’s the duality in there as well, and he’s aware of the ebb and flow, the ships gliding by. But he finds them beautiful. This is another thing about Wilko Johnson: Canvey is beautiful to him. I have interviewed him. He really sees a true beauty in Canvey: a beauty in the fact that the green, pleasant land of Kent is just a stone’s throw away but you can’t reach it. He seems to understand that. So he’s happy with what he’s got and making it beautiful with his music and how he relates to it. I think I remember him telling me he grew up with the sound of the pile drivers into the mud when they were building Coryton. I kind of said to him, “do you think that’s in you – that it’s the reason for your staccato guitar playing?” I don’t think he bought it, I think it was a bit too out there for him, but I see a connection between a strange industrial geometry in his guitar playing, and the kind of repetitive ebb and flow and the industrial mechanics of the Estuary around him growing up.

I think it’s the two things in his playing: that industry that makes Dr Feelgood sound like a well-oiled machine, but also you hear a spiritual, ancient feel in his playing. In that Zoe Howe book there is a poem he wrote about a trance-like state in India, about the Hashish Eaters, the myth that goes back to Middle Ages interpretations of Middle Eastern stories. I feel there is this hypnotic quality to his guitar playing as well.

Yes, and he understands that kind of layering, he knows where it’s all coming from. He studied medieval literature and he’s obsessed with Blake and spiritual visitations. He’s not just going from the gut – he does, but he also knows where this sound comes from, and how it will affect you, and how it can affect you if you have the sensibilities he does. I think when he is playing the guitar he’s not just a rock star playing a guitar, it’s something deeper than that. It goes way back and it’s ancient.

I think that’s why converts are so sold on him. I have friends who’ve caught him on the off chance at a festival and just been like, “Who’s this old bloke on guitar?” I think it’s when you realise what’s in it, it’s almost like you’ve been hypnotised by it.

When you get older you do have your trademarks and you become a parody of yourself because you have to. He knows that. He does the whole machine gun thing on stage still. But he’s obsessed with guns. There’s a gun that used to be William Burroughs’s that was given to him, that I held, but he’s also got AK47s, a big shotgun…

Do any of them work?

They’re all decommissioned apart from the William Burroughs gun, which works. The actual gun actually cited in Naked Lunch. A musician from his Blockheads era gave it him, and they just used to sit around the flat doing target practise, a la William Tell. You know musicians talk about their guitars in a certain way; he’s like that with his guns.

Photo by Emily Mesher

In the book, I felt that Uncle Rey was an alternate version of Wilko, with his obsession with the stars and things. It is like Uncle Rey is a kind of traumatised Wilko who couldn’t ever lift off.

Yeah, because for a time, before this renaissance in his latter stages of life, there was this whole decade when he didn’t do anything: I don’t know if this is true, but people told me that he just sat in his room listening to music. He didn’t see anybody, go anywhere. So the more I think about it, that idea of Wilko Johnson’s solitude has probably infused and created the sense of loneliness in Unle Rey’s existence in the book. I try to convey that this is a man who has spent a lot of time on his own, and the only way he has wanted to connect through the world, or to one person in particular, is through these recordings. There was this desire to reconnect. If you think about it, there must have been a desire to reconnect in Wilko, which he now has fulfilled – but in a very odd way: it’s our obsession with death that has created this renaissance, the rebirth. It’s all very Greek and Freudian, which sadly is horrible but fascinating as well. And from what I am hearing he is actually doing really well.

Will you write about the area again?

Yeah, I think so. The next book I am writing is set in London, rather boringly. But it has to be, because it’s about rich Londoners and poor Londoners. But I want to write something really short and precise, like novella, about [secure yet inhabited MOD testing ground] Foulness Island, at the end of the Estuary.

Have you been on there? You need to have a prior arrangement: there used to be a pub on there you could visit but it’s closed down now.

I’ve driven up to the gate and stared at it. It would have to be a very short novella because there is not really scope to do much on Foulness. But it’s such a ridiculously amazing place.

It’s the closest I have ever gotten to going back in time, going through the village there.

I’d like to do that but there are a couple of people who have Foulness in their sights.

Jack Barnett from These New Puritans used to tell me he wanted to live there.

I love their work. For me it is like a huge work of literature. I’d love to be a musician with their sensibilities. They are all encompassing. They don’t just want to entertain and give pleasure – they want to absorb everything to its minute detail, sounds and repetitions.

There is so much in the music: field recordings that you would never realise were there.

Their entire body of work is a work of art itself. They are artists in that sense. They know what to take from the world around them and it doesn’t matter if they successfully put it all back together, it doesn’t matter if it doesn’t work, it doesn’t matter if it can never be put back together. I think they are Deluzian in that sense – they know that there is no Grand Narrative, just these broken shards around us, and we make do with them what we can. You can forge something from them.

Jack and George Barnett grew up with Lee Brilleaux around, he was friends with their parents. And they are similar to Wilko Johnson, how they just seem to absorb the world around them and re-articulate it so well.

There is a thing that Tom McCarthy the novelist says. Writers now, because literature is pretty much dead – and it is pretty much dead, which is no bad thing, and not just because of technology and the internet, it’s because culture is different now: it is a visual culture and literature isn’t the thing we turn to. He says all that writers now, unless they want to repeat what has been written formally and stylistically, have got to be a) an anthropologist and b) an archaeologist. You’ve got to study the cultures around each layer of literary history, but you’ve also got to scrape away, looking for that perfect pristine piece of bone. That’s kind of what I aspire to do. Vulgar Things is a kind of work of archaeology in that sense. I am scraping back the traces of this area, of the stories I’ve used to create it. That’s basically what the novelist’s job is now, writers like Tom McCarthy would argue. I think to me that’s far more exciting than trying to be an original literary hero. There’s so much more fun in excavating the dead carcases of literature past. That’s basically what These New Puritans are doing sonically: they’re retracing histories and myths of the area, but also histories and myths in their musical lineage and re-echoing them in their new compositions.

And it’s a different thing to hauntology. I was interested that earlier you distanced yourself from hauntology, which I understand. Especially with music, it has become a package, and I think there is a lot of one-note stuff coming under the genre, all of which are quite nostalgic.

That’s exactly why I wouldn’t say I was a hauntologist – because I don’t want people to think I am nostalgic for a literary past. I dislike nostalgia in novels. That’s why the book is in present tense: I couldn’t have any reflection in the book as nostalgia may creep in, or something may be misconstrued as nostalgia. Jon is just moving along, trying to find the next thing. He doesn’t really stop and think about why he’s here. He’s just caught in a perpetual loop. There is a lot of Schopenhauer in the book: this sensibility of being caught in the present, there is no future, there’s no past, you are in this perpetual present. Schopenhauer used to laugh that the only reason we walk is so that we don’t fall over. That amused him. All Jon in the book can do is move forwards. Everything passes him, in that sense, other people’s voices pass him by. Nothing in his life meets him head on. It’s how I see life and reality: as a continuing present that we can’t really escape from. If we project ourselves into a future full of hope, it’s a form of fiction and if we look back into the things that have happened it’s an architecture of memory, so it’s never real. The only thing that is real is the moment when he feels like tingling of the container ships. That is the ongoing energy within the book.

I feel Southend and Canvey are the perfect places to tell that story. There is something thrillingly Sisyphean about the Southend Pier, this mile and a third road to nowhere.

There seems to have been this great effort to create the longest pleasure pier in the world, and when you get to the end of it there is pretty much nothing there, and when you looking out into the estuary, there is pretty much nothing there because it’s so flat, with nothing really to look at. All you get is this sense of false hope which is signified by these young guys on the end of the pier fishing, hoping for the catch. There is this kind of continuing flux of hope, which is a form of hopelessness, which is strangely beautiful as well. It’s an amazing place to go to even though there is not much there. That’s why the story begins at the end of the pier, plucked out of the nothingness.

And a key theme of the book is the kind of misogyny–as-entertainment that is very visible in somewhere like Southend. Strip pubs like the Foresters’ Arms and the places on Lucy Road, which are indicative of a culture that seems to be going through some kind of boom at the moment. It seems like there is a conscious calling out of this misogyny in the novel.

Definitely. There is a real undercurrent in it; the thrust of all the male characters is through the male gaze. All their problems are because of it and all their hopes and dreams are because of it, and they are trapped in this kind of misogyny which underpins the world around them. It’s all caught up in that accepted, unknown, unbeknownst misogyny that cradles male ego. Jon is kind of not aware of it, but he’s somehow struggling with it.

What I noticed in modern society is that this cradle of misogyny is validated in places like Lucy Road, where all those nightclubs and bars are built around the male gaze. It’s all for men to play out their existences in front of young girls. That’s why you get the really tacky strip clubs and the really tacky pubs that have the ‘exotic’ dancers in them. It’s what’s happening in smaller towns as well, and in the big cities: these really expensive clubs, but they are just basically a posh strip club. It’s everywhere. Throughout the book, they are kind of part of it but there is nothing really they can do about it. That’s kind of what worries me when I see packs of young lads in pubs, it’s a really testosterone-fuelled misogynistic humour and existence that are played out in these places, where they are allowed to be like that, where it is normalised. And, plus, through media now, and the Americanisation of the male gaze, it is all around us. It is normalised when it becomes a commodity.

I think it somehow chimes with the place: the post-Thatcherite atomised logic of Essex. I find it interesting that you are from Manchester, the North, with its trade union and socialist traditions that go back very far, so maybe pick up on these things quicker?

What I notice as a Northerner, there is a history of industrialisation and a community workforce in that sense, whereas down here there is more of a sense of individualism, and a sense of what we are out to get. You kind of see that reflected in the seediest ways. You see it reflected into positive ways, don’t get me wrong, you see the good things. But when you reduce it to its base level in the way that Bataille would, and you see the real matter of the fact, it’s the seedy male gaze being played out: What I want, what I want to get. I’m not saying that doesn’t happen up north either. You go to small towns up north it’s the same, especially seaside towns. If you go to Blackpool. I’d love write a novel set in Blackpool. Blackpool right now is just changing beyond all comparison to when I used to go as a child. Their saviour was going to be becoming casino capital of the UK – they’re clinging on to any kind of false hope. It always happens in seaside towns. Before Brighton was gentrified it had this underbelly that Southend still has. It will disappear in Southend because Southend is getting increasingly gentrified, and that seediness will eventually be marginalised and removed. When I first went to Margate in the 90s, that place was utterly bizarre. Now there is a real onset of gentrification happening there, which is a vulgar thing in a different way. It is tied in with capitalism, in the way that the seediness is, the dark side – the cheaper side of it – translated into male petit desires. That’s why Southend is still an interesting place to me: you go down to that seafront at night and it’s another world, and it’s a male world.

It’s a violent world, quite Ballardian actually.

It is a completely Ballardian world, and with that desire, comes the violence. They are hand in hand: male desire, male gaze, will bring violence. Especially if there are more men around than women.

Lee Rourke’s Vulgar Things is out now, published by Fourth Estate. Trying to Fit a Number to a Name is forthcoming on Influx Press