Anat Ben-David photograph courtesy of Ole Dyrseth

Stian Westerhus is setting up an arsenal of audio gear in a half full car park in Norway. The Parking Garage under Oslo Konserthus is remarkable in how unremarkable it is; an open-sided concrete, steel and tarmac delimited space under a squat, voluminous building. It has a low ceiling supported by giant reinforced concrete legs, clad in a veneer of dirty pink and orange igneous rock smeared dull by exhaust fumes and weather. We could be almost anywhere…

It can be irritating to watch a guitar player spending hours fine-tuning a pedal board the size of a football field, just to play at exactly the same tone all evening. Westerhus makes full use of his equipment, however. He has two Roland PK-5s, some FX units, two laptops, Maschine, a mixer, a lot of amplification and lights, but you certainly get a lot of bang for (his) buck.

He starts off in an extended noise segment, marshalling various tones and bursts of noise and processing them off into odd sonic tangents as he goes. The name of the piece is Impossible Metallic Slaughterhouse, inspired by the original BBC film adaptation of Crash! from 1971; and as he reduces the volume down to whisper pitch, you can hear why. The sound of the traffic using the sliproad directly behind him adds an air of unpredictability to proceedings. Yeah, of course, the concert organisers must have known that the piece would interact with ambient vehicle noise, but did they realise that at this exact moment a large brass band would be marching in the nearby Palace Park? The effect is amazing. A serendipitous clash of Norwegian music, moderately old and very new. The disembodied pomp of tradition drifts gently in on the breeze but then gets lost for good as Westerhus picks up steam again.

He summons up a dry drone out of static and underlays it with thick bass pulses, harmonising and pitch shifting his guitar to get Moog-like tones and expansive Ligeti choral sounds; then he uses a bow to draw Orca wails into the mix. The piece is very dynamic in all respects; Westerhus himself looks more like a timeless rock & roller than an avant garde musician, and in fact snatches of foot-on-monitor rock dynamism interject into the performance at several points; desert blues, no wave and stoner rock elements all complement the exciting concept, performance and location.

As exciting as it is to be experiencing loud amplified guitar music in a car park, the venue is, in functional terms, an unremarkable space, a transitory zone; the kind that exists in any given modern metropolis. This is why it is perfect for the launch evening of Only Connect. This annual sound art festival, now in its tenth year, tries to draw new channels between music and other arts, and this year is dedicated to celebrating the life and work of J.G. Ballard.

Photograph of Stian Westerhus courtesy of Thomas Ekström

I was going to start by saying that Oslo is a very Ballardian city. And in its concrete flyovers, internationally standardised construction tropes, warm sodium-lit underpasses, partially filled impersonal office blocks, partially built impersonal office blocks, partially filled high rise luxury apartment blocks, I guess it is. However, as China Mieville points out in the introduction to Miracles Of Life, the whole modern world can be described in exactly the same way:

It has become a cliche to point out Ballard’s canonisation into adjectivalism, to stress that in its outlandish alienations and estrangements, the world has become utterly Ballardian. But not only is that a cliche that is true, it is one that stresses Ballard’s irreducibility. Modernity must be described as Ballardian, because there are no other words that mean what that word means. It is its own explanation.

Spending days on end reading, discussing, watching, listening and absorbing other people’s interpretations of Ballard, you don’t just start to see things from his worldview, you realise that you are literally trapped in his world. Most things I experience at Only Connect are Ballardian. In fact, just presume from this point on in the feature that everything I mention is Ballardian unless I say otherwise.

After Westerhus, it is but a short (and slightly dangerous) walk to the Diorama, Stenersenmuseet where Alwynne Pritchard’s Kingdom Come, based on Ballard’s last novel, is being performed. As Adam de la Cour and Stine Johanne Janvin Motland sit on chairs behind microphones, and Syed Zubair Ali sits cross-legged between them at his harmonium, we are warned to turn off our phones and to not make any noise because of the use of live sampling during the piece. De La Cour and Motland start up a disjointed ‘conversation’ in several languages and dialects. When this bizarre chat comes round again, modified, it interacts with what is being said live in really odd ways. The piece that Ali performs and sings under this babel is breathtaking. As this is unfolding, some quotes from the historian Anders Ohnstad on feng shui and how impossible he finds it to understand Ballard’s writing because of English neuroses and anxiety over class are flashed up onto the wall. I start to get slightly irritated, but then my plastic chair breaks with a resounding snap. As I fall to the floor I’m mortified, as I’m sure I can hear the sound of my arse splintering through plastic caught in the loop of the music. I consider running out of the venue and not returning to the festival. So retrospectively I have to admit that maybe Ohnstad has a bit of a point after all.

Photograph of Stine Johanne Janvin Motland and Syed Zubair Ali courtesy of Thomas Ekström

Anne-Hilde Neset, the festival’s Artistic Director, who has done an excellent job in curating this event along with Audun Vinger, admits that perhaps Ballard isn’t the most obvious choice for such an event, as he isn’t particularly associated with the creation or criticism of music himself. (He certainly didn’t have the clearly defined – and latterly sometimes slightly desperate – synergistic enthusiasm for sonic youth culture that William Burroughs did, for example.) As Ballard said to FACE magazine, "There’s no music in my work. The most beautiful sound in the world is the sound of machine guns." Later in life he claimed that he didn’t own any records, but would happily listen to Serge Gainsbourg if his girlfriend put it on the stereo. Ballard did have favourite songs, but they were very, very typical for someone of his age and class.

The Langham Research Centre use this to their advantage when they present a piece based on the author’s selections for his 1992 appearance on Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs. The sentimental, bubbly pop and classical tracks that he picked are treated with spectral and dubby effects, as members of the LRC read out extracts from The Sound Sweep and The Atrocity Exhibition. It’s an effective and immersive performance, and I’m sure this is the most subtly disconcerting ‘The Teddy Bears’ Picnic’ has ever sounded. The overall effect is like listening to Book At Bedtime with Leyland James Kirby as the producer.

If you’re interested, these are Ballard’s choices: Henry Hall ‘Teddy Bears’ Picnic’; Bing Crosby & The Andrews Sisters ‘Don’t Fence Me In’; Rita Hayworth ‘Put The Blame On Mame’; Marlene Dietrich ‘Falling In Love Again’; Mozart ‘Non So Piu Cosa Son’ (from The Marriage Of Figaro), Astrud Gilberto ‘The Girl From Ipanema’; Rossini ‘The Barber Of Seville Overture’; Noel Coward ‘Let’s Do It’.

During his first year of internment in the F block of the Lunghua camp, just outside of Shanghai in 1943 – before things got really grim – Ballard admitted that he had a great time as a child prisoner of war. Every Tuesday, the internees would put on full-scale musical productions, including several by Noel Coward. Two years later, after Hirohito’s capitulation broadcast in 1945, Ballard was still young enough to be uncaring of personal danger, and yet now old enough to tough it on his own in the deregulated, postwar zone of the Yangtze River Delta. He made the solo trip from Lunghua back to a bomb-wrecked Shanghai. While walking along a train track, he was stopped by two Japanese soldiers who had a young Chinese man tied to a post. Their prisoner was singing to them in a desperate attempt to gain his release. They ordered the boy to take his belt off, and made him watch while they used it to choke their prisoner to death, before sending him on his way. When he eventually reached his parents’ house, he found it exactly as they had left it before the war – one of the few houses that had escaped being stripped bare, bombed or otherwise ruined. Before he returned to England in 1946, he apparently spent many happy nights back in his old house with his new neighbours, American intelligence officers and their Chinese girlfriends, singing along to the Andrews Sisters on the wireless.

Some generations earn the sentimentality of their popular music with greater desert than others. As the character Amanda observes in Private Lives, "It’s extraordinary how potent cheap music is." The author of the play? Noel Coward of course.

Rounding off the night is a set from Kode9 who forces everyone toward the rear of the already sweltering space with a very heavy but user-friendly set of dubstep, synth, footwork and grime. As Neset points out, "If Ballard loved the sound of machine guns then this makes Kode9 a very appropriate choice, given the book he wrote." The producer published a densely written but highly regarded work on audio weaponry called Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect And The Ecology Of Fear (Technologies Of Lived Abstraction) under his real name, Steve Goodman, in 2009. With some of the artists featured on the bill, you can tell that they are struggling to make a real, concrete connection with the work of Ballard – something that is kind of understandable if you work in the field of new instrumental music. There are no such worries with Kode9 however. Tonight’s set is very tightly themed from the opening, heavily processed samples of Ballard himself onwards.

The theme is the author’s time spent in Shanghai, something that comes natural given grime and dubstep’s fascination with music that comes from the East. As Dan Hancox says in his enjoyable book Stand Up Tall: Dizzee Rascal & The Birth Of Grime: "Before it hardened down into the fabric, there was another orientation of futurism audible in grime’s creatively molten moment: what’s come to be known as sinogrime, a glitch of Chinese instrumentation in grime’s normally stable sonic geography… Around 2002-3… a few young grime producers from the east London postcodes suddenly lurched further east than they ever had before. Sinogrime is the sound of Shanghai tower blocks and the millennial promise of the newest superpower, refracted through the scuffed windows of the Crossways Estate."

And sure enough, mid-set Kode9 drops the still astounding-sounding ‘Sittin’ Here’ by Dizzee Rascal, perhaps the best example of sinogrime there is. He marks the boundary between a heavy, ribcage bruising bass section and a loosely (and removed by several steps) Chinese influenced instrumental section by playing Fatima Al Qadiri’s ‘Shanzhai’. This sinogrime-referencing track is an excellent choice for many reasons. The word ‘Shanzhai’, as Adam Bychawski points out in this great review, is a Chinese term that has come to mean counterfeit goods and, even more recently, lookalikes or parodies. The song is in fact a cover of Sinead O’Connor’s ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’ – itself a cover of a Prince song – but in this instance sung in nonsensical Mandarin, something of a joke at the (Western) listener’s expense. Al Qadiri, like Ballard, grew up in a war torn country: she lived through the invasion of Kuwait and subsequent Gulf War. She compares her home country to a notional China, which represents the anxieties of Western capital. Kode9 also plays her track ‘Shanghai Freeway’, a feverish vision of never ending motorways and theme music for half-built luxury shopping malls. Of course, from here it’s but a hop, skip and a jump to a pumped and pitched up footwork remix of Kraftwerk’s ‘Trans Europe Express’ another song which can be read as a Ballardian exploration of transitional zones. And then there is some great use of more spoken word from the author, and perhaps the most Ballardian of all modern musical artists, Burial.

Photograph of Kode9 courtesy of Thomas Ekström

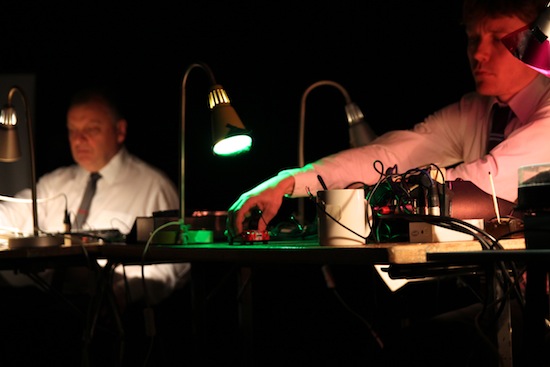

On the second day, Langham Research Centre put in another excellent performance, this time in a gallery space and art/design bookshop called Kunsthall. In a darkened room, they sit behind a row of desks only lit dimly by angle poise lamps. There is a mass of untidy looking equipment in front of all of them. The piece, ‘Muffled Cyphers’, is an audiovisual performance based on various Ballard texts including The Atrocity Exhibition, Vermillion Sands, Westway Angels and The Terminal Beach. Or to be more precise, the LRC have extracted descriptions of sound and music from the texts, as well as other concepts and snippets of dialogue etc that loaned themselves to sonic reinterpretation, and used these as the building blocks for the piece. In real terms this translates as a bewildering and beguiling tapestry of sonic fragments – snatches of radio broadcasts, whistling oscillations, field recordings, processed sonic scree, live input from amplified objects. The keen of ear will hear a heavily echoed snippet of ‘Teddy Bears’ Picnic’.

Two vintage flywheel slide projectors are used to flash up urban images of tower block corridors, underground car parks, CCTV cameras, convex security mirrors, underpasses, motorway flyovers, gearsticks standing erect… ready, no doubt, to penetrate one’s thigh. The projectors are part of a very closely observed aesthetic. The stage set up looks like something from a George Smiley novel; as well as the lamps, there are cassette recorders the size of breezeblocks. One chap in a knitted tie seems to be contributing to the overall effect by rubbing what appear to be a couple of 2HB pencils together, manipulating an amplified Matchbox car and lowering a spoon in and out of an amplified mug. The whole event is so fluid and fast it’s hard to really get a grip on the sounds being created; vintage jingles phase in and out of clarity, their sense obscured by oscillator noise, the jabbering of overlaid voices, fractured rhythms that dissipate just before bedding in. There are some Ligeti-like vocals, a doomy synth progression and then silence, as the poised angle lamps fade to blackness.

If all of this sounds a bit like the Radiophonic Workshop trapped in some dystopian future bunker prison, well, fair enough: the LRC are all BBC producers during the day. The whole effect is unnerving and genuinely psychedelic, like The Focus Group ‘remixing’ Berberian Sound Studio.

Photograph of Langham Research Centre courtesy of Ann Kristin Traaen

Following this, electroacoustic composer Joran Rudi presents Concrete Net, a CGI film where distances in the solar system are used to construct and organise sound. Some of the source audio material comes from readings from Concrete Island, but has been processed so heavily you can’t tell what it is. Other than this, it’s not really clear what the piece has to do with the theme of the festival, and that’s despite the composer introducing his work first. I can’t say I think much of the film but then, for the record, if it’s not Toy Story I’m predisposed to hate computer animation. This is like the fevered cheese dream of a Pixar employee who worries he has sub par wireframe skills. However, it should be said, the sound element of the piece is fantastic. There are diffusion speakers placed round the room, and if you wanted to be generous you could say the audio is on message, because this is probably what it sounds like to be inside a car caught up in the middle of a motorway pile up, except slowed down to one thousandth of the speed.

It’s tricky knowing how much resonance Ballard has outside of the UK. But given that I’m about to attend a screening of three short films by the Swede Solveig Nordlund, and then see her in conversation with the Australian Simon Sellars – who runs excellent resource Ballardian.com and is also co-editor of the great anthology Extreme Metaphors: Interviews With J. G. Ballard – in a cinema in Oslo, it’s fair to say that there must be some. Walking along the length of Oslo’s waterfront, one is certainly put in mind of the author. There are the brand new so-called Barcode buildings, either side of the train tracks entering Sentralstasjon in Gronland, threatening everyday folk’s uninterrupted view of the fjord. There are the gentle angles of The National Ballet & Opera, which allow an easy perambulation right up to the highest point of the roof. There is talk of a massive promenade which will completely change how Oslo looks, and there is now also the massive Tjuvholmen peninsula development of high rise apartments, boutique hotels and waterside bars, ready for an influx of tourists which hasn’t yet arrived.

Nordlund was obviously well-liked by Ballard, as she crops up in an incidental character in his later fiction, and while I can’t speak Swedish, Sellars declares her short film Low-Flying Aircraft to be the most worthwhile Ballard adaptation, "better than either the Spielberg or the Cronenberg". Later there is a an intense performance by three percussion artists of a work in progress called Procession And Drought by the composer Oyvind Maeland which explores the multiple effects that dampening various drums, bells, gongs, cymbals etc can have.

To celebrate the changing architectural face of the city, the festival has commissioned some site specific music pieces which can be downloaded here. Probably my favourite is Akrobaten a composition by Stine Sorlie which was written with the steel, glass and concrete pedestrian bridge which spans the trainlines in mind.

The evening’s events are set in boutique hotel The Thief in Tjuvholmen: a throbbing grotto of very expensive contemporary art piled high, cheek by jowl, in a vandalous act of aesthetic dissonance. In the lobby there is a clock that is also a loom which is slowly knitting a scarf made from gold. Next to that there is a 25-foot high canvas of a cowboy trying to lasso a bucking steer. You can book a night in a room designed by the supergroup Apparatjik which includes a mirrorball in the bathroom and a projector that allows you to beam a band member of your choice into your bed. So you can sleep with a 2D version of the bass player from Coldplay or Mags from a-ha!; the choice is yours. In the restaurant next to a large poster of a woman with pineapples pouring out of her trousers is Norway’s most highly insured painting, an original Andy Warhol of a New York drag queen with a giant afro.

I overhear someone in the foyer sarcastically asking a companion, ‘Hmmmm. But is it in good taste?’ Certainly The Thief is more Caesar’s Palace, Las Vegas than it is Tate Britain, London, but at least it’s free from the tyranny of good taste. I mean, who wants to stay in a hotel where the Rothko prints have been chosen to match the expensive carpet, where the lobby’s playlist has been curated from Mark Lamarr’s very own personal collection of ska 7"s, and you can stay in a low-carbon footprint penthouse suite designed by Thom Yorke and Tao Lin? If I had the money I’d want to stay in a hotel with a roof terrace that had live flamingoes, a naked brass band, polar bear taxidermy and a laser show every night at last orders.

After a sense and aesthetic boggling trip round The Thief we go to room 308, where Oneohtrix Point Never has designed an installation for Only Connect. The hotel room is pitch black. In the corner there is a table made from a piece of wood supported by four neat piles of J.G. Ballard novels, lightly underlit in ultraviolet. Somewhere in the room a loop of a minimalist synth refrain is playing. Compared to the building that houses it, it’s all rather, well, tasteful.

On the final day, after Simon Sellars delivers a well-thought out and engrossing lecture on Ballardian cinema, we’re treated to some readings by Iain Sinclair via Skype. As we watch a split screen film of the M25, the author reads out Ballard’s ‘What I Believe’ and then an excerpt from his own London Orbital that details a meeting between the pair. A few minutes into the reading, the Skype signal keeps on breaking up, transforming the piece into a series of vocal gurglings and a series of ominous non-sequiturs, adding a new and unintentional layer of meaning to the piece.

It’s been a really excellent event, and it ends on a killer one-two knock out. First is London based artist and member of Chicks On Speed, Anat Ben-David, performing her extraordinary MeleCh show. The basis for this show was a long period of automatic writing; the text she was creating being mainly dictated by the way the words sounded, not what they meant. She then learned the entire text – and how it was to be pronounced – by heart by employing mnemonic means, creating a narrative of sorts. Tonight she also uses various digital vocal manipulation techniques and costume changes to distinguish between different characters she is giving voice to as well as performing in front of a film. There is a dense textural and imagistic inter-connectivity between all the songs, films and the performance itself, which is by turns psychedelic, funny, disconcerting, brain warping and really enjoyable.

Then it is Carter Tutti performing the world premier of Impulse Response II, a profoundly satisfying new piece, which suits the festival right down to the rubber-scorched tarmac. They have remixed the 1971 BBC short film version of Crash! which features Ballard himself and Gabrielle Drake (Nick’s sister) in starring roles, processing it into a fantastic grain of ochres, pale greens, grey blues and oozing crimsons. An echoing dubby electronic beat, becomes tougher and more insistent. Time-stretched, screeching synth tones make the perfect match for barely discernible auto wrecks superimposed over a girl’s bloodied face lying crushed against a steering wheel. No pun intended but it’s a driving sound that moves into industrial techno territory before switching into cavernous, almost Bug-like digital dancehall zones. And it might well be a hypnotic sound they’re creating but the occasional bursts of sheet metal tearing dissonance and reverberating electronic drones keep the crowd fiercely entranced until the end.

The next morning I have some distinctly un-Ballardian pickled herring and set off for the airport, saying a quick prayer for a distinctly un-Ballardian flight home.

Photograph of Carter Tutti courtesy of Ole Dyrseth