Born 100 years ago today, though he claimed to have arrived here from the planet Saturn, Sun Ra provoked a range of emotions in his extraordinary lifetime – from anger, indifference, confusion and oblivion, to astonishment, awestruck, cultic devotion and elation. He was, in his own mind, the first black man in outer space decades before they even built rocket ships. Unacknowledged and overlooked, ploughing a lonely cosmic furrow, he blasted open the portals to a notional future for jazz and post-jazz in an era when racist legislation held brutal sway, not least in his hometown of Birmingham, Alabamba.

He gained international renown, particularly in Europe the late 1960s where he and his big band the Arkestra were feted as titans of the avant garde, yet was chronically hard up, once having to sell the master tapes to one of his albums just to pay the phone bill. He was written out of Ken Burns’s Jazz, that Wynton Marsalis-curated TV series – jazz purists treated him with suspicion for his embrace of electronic instruments in a genre that was supposed to be about acoustic conversation between players. None of that for Ra, a master with musical disciples, whose urgent, joyful noise was intended to jolt humanity from its earthbound inertia; “Space is the place!” Yet, he has long been revered by rock music’s more inquisitive adventurers, a distant, gigantic touchstone who long since surpassed rock’s relatively modest electric dreams. MC5 and Sonic Youth worshipped at his altar, the NME made him a cover star back in their more intrepid times and even Pete Townshend is a huge fan, having by his own account bought 250 of his vast catalogue of albums on a single trip to a Chicago record store.

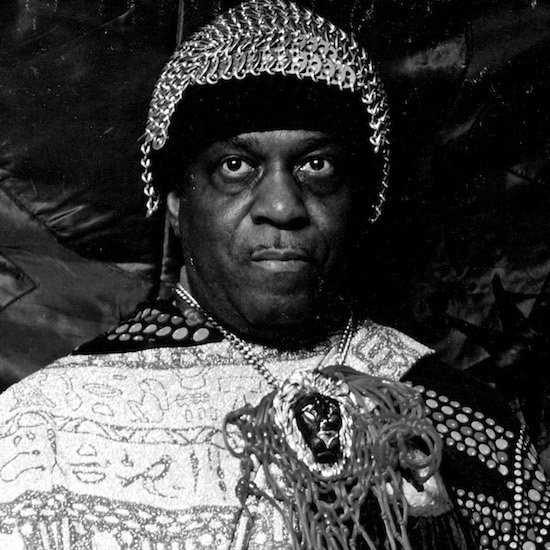

This ageless old man, this one man meteor storm is Sun Ra.

It’s easy to get off on the wrong foot with Sun Ra; to titter at the florid robes in which he insisted on decking his Arkestra, his sometimes TV aerial-like headjoy, his apparently humourless insistence on his extraterrestrial provenance, his personal philosophy which harked back to Egyptology, numerology and the bible from which he pored over, misguidedly in the view of any self-respecting rationalist or sceptic, in search of some Ultimate Truth. You might be tempted to have a bit of a laugh at the low-rent, blaxploitation-style production values of Space Is The Place, the self-mythologising movie he made in 1972 which depicts him returning to the USA in a rocket ship fuelled by music. Or, you might randomly pick the wrong album by way of introduction, in which he appears to be playing relatively straightforward, mid-century big band bebop. Persevere, however, and you’ll come to understand the devotion he inspired in his group, including players like John Gilmore, a saxophone colossus who might have rivalled Sonny Rollins or even John Coltrane had he chosen to go his own way. Instead, Gilmore pledged lifelong fealty to a man who demanded such commitment to musical duty that he had tried to persuade him not to go to his own mother’s funeral.

He was born Herman Blount in 1914, and, though deeply embedded in the African-American community, could not possibly have failed to be aware of the racial segregation that was a given in his formative years. The young Blount took refuge in both music and books, reading obsessively, everything from sci-fi comic books to the Old Testament; a rare, trapped soul yearning for impossible escape. Something better than this had to be out there somewhere. He was drawn to jazz but shared none of the lascivious appetites which were meat and drink to the music, and key to its prohibited appeal in the straitlaced early 20th century. He rarely drank, eschewed drugs, was a fastidious, healthy eater and apparently asexual (he suffered from a chronic testicular hernia) someone who had sublimated the urges of the flesh into the all-consuming, holy, insomniac, voracious pursuit of his music and his self-taught philosophy.

He saw music as the art form in which he could achieve the transcendence for which he yearned, as espoused by the 19th century Russian composer who dreamt of a music that dealt in light and colour as well as sound. Musical instruments took a while to catch up with such visions, or the Art of Noises as dreamt of by the Futurist Luigi Russolo. In his early band leading days, Ra had a hard time explaining the future of music as he envisaged it, in which the musicians would somehow channel electricity through their instruments. The horn players wondered aloud if they wouldn’t be electrocuted. However, when any kind of new technological device appeared on the market, such as the first commercially available steel tape recorder in 1937, or the Hammond Solovox, a small electric keyboard in 1939, Sun Ra was an early, enthusiastic adopter. Around this time, having led the short-lived Sonny Blount orchestra, Ra experienced the epiphany in which he recast himself as an alien visitor and would be saviour, ultimately destroying all paper evidence of his previous identity and formally changing his name.

A conscientious objector in World War II, Ra managed to impress the judge who sentenced him to jail. "I’ve never seen a nigger like you before,” he said, to which Ra/Blount replied, ”No, and you never will again.” After the war, despite having long outgrown the conventions of swing in his own mind, Ra got his first job as pianist and arranger for Fletcher Henderson, then in his career twilight, whose work he knew off by heart. Ra moved on, working in smaller combos with the likes of Coleman Hawkins. In the late 1940s, he made one of his first known recording, a strange, sweet and sad piece entitled Deep Purple, on which he plays the Solovox accompanied by Snuff Smith on violin and drummer Tommy Hunter using a telephone book as a percussive instrument.

He was already in his mid-30s by this point but still seeking out both the personnel and the means to realise his sound visions. He would visit Robert Moog’s studios and, dismayed that he saw only white people availing of their facilities, declared, “Black people are behind on these things and they’ve got to catch up.”

Gradually, he did. By the late 1950s, he had accrued a large, shifting ensemble, in some ways a throwback, given that the big bands of the pre-war era were no longer considered economically viable, and jazz in overall commercial decline. By 1958, the Arkestra were decked out in the futurist/Egyptologist colourful garb which would become their hallmark, but which at the time cut a pointed contrast with the tendency towards smart, sartorial sobriety preferred by the likes of the Modern Jazz Quartet. In anticipation of the mandatory freedom of New Jazz, Ra instructed his players, on pieces like Ancient Aethiopa to play as if from scratch, leaving behind as if like earth itself, popular harmonic conventions, disporting freely in the air. This was both ancient and future music.

In the 1960s, touring and releasing albums like 1965’s Angels And Demons At Play, Sun Ra at last felt among vaguely likeminded kindred spirits – John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, although they didn’t share either his cosmological extravagances or interest in electronic instruments. Titles like ‘We Travel The Spaceways’, ‘Rocket Number Nine Take Off For The Planet Venus’, ‘Tapestry From An Astroid’ and ‘Where Is Tomorrow?’ actually sat quite well in sci-fi obsessed young America, almost kitsch-like. But Ra was keenly aware at this time that while Yuri Gagarin was piercing the envelope of space for real, black people were still having to fight and die for basic civil rights in the Deep South. Given the loftiness of his ambitions, to have to address such disparities was almost beneath his dignity; he considered himself post-racial, beyond black or white. But they burned hard with him, pained him like his hernia. By the late 1960s, while his contemporary free jazzers either died away or continued to observe the new academic strictures, Sun Ra went into overdrive, an interstellar rage. At Les Nuits De La Fondation Maeght in 1970, he unleashed this.

Come the 1970s, with Ra now approaching his 60s, the Arkestra’s commercial fortunes continued along a low, flat line – the group were a barely feasible project, living communally and frugally in New York at or below the breadline, with Ra a hopeless accountant, selling newly pressed records on the street and on the hoof, playing whenever and wherever they could, one week playing at some grand festival on the European circuit, feted as the great pioneers of the age, the next playing to seven people in Philadelphia. They travelled to Egypt, where they were asked to play for local dancers, who were sent fleeing in horror from the venue when Ra unleashed his fearsome Moog synth. By this time, however, the influence of Ra was being felt in the colourful, stadium funk particularly of George Clinton, who arrived onstage in a spacecraft, chuckling “whoever would conceive of a nigger in a spaceship?”

It was in the late 1970s that I first became aware of Sun Ra, via Chris Cutler’s Recommended Records, whose limited catalogue also featured, and introduced me to, AMM, Magma, Faust, Captain Beefheart and Pere Ubu among others, a veritable solar system of ingenious eccentrics who put earth to shame. Media Dreams, recorded in Italy in 1978 with a pick-up combo and featuring the uncanny accompaniment of a drum machine, like a small, outboard motor on a cosmic hovercraft, was my First Contact with Sun Ra, my never-hear-surf-music-again epiphany. Fucking Heaven and Hell.

I dived into what morsels I could acquire from catalogue, including a scratchy old copy from Leeds Record Library of The Solar Myth Approach Vol. 1 & 2, which ran the full gamut of Ra – the imaginary court music of ancient Pharaohs, Moog black holes, lucid moments of jazz tenderness and beauty, all of which sounded like it had been recorded light years away. And then, in 1980, came this, perhaps my favourite Sun Ra track of all, in which space is depicted not as remote, empty, uninhabited and indifferent, as in the bleak, static renderings of Tangerine Dream, but as where all the action was, as depicted in Ra’s synths, chattering, plunging, incandescent, swirling – the place that awaits, for music, if not mortals.

Despite the sheer artistic vigour of his later years, in which he put musicians a third of age to shame, Sun Ra was not able to live up to his claims of immortality. He died in 1993, aged 79. The last time I saw him was at Ronnie Scotts, a few months earlier, a living and dying legend. The Arkestra had to play most of the gig without him, as he was too incapacitated to play a full gig. However, for the last number, he was walked to his keyboard, supported by two helpers on either arm. Lowered into his seat, he slowly picked out a series of sublime bass notes, finding tunings and depth charges, unfathomable and uncharted, which reverberated to your marrow. Even as his body gave up, he still had it.

Ra’s legacy permeates in subtle, allusive ways throughout contemporary music, consciously or unconsciously. There’s Quasimoto’s sampling of ‘Astro Black’ on the track from The Unseen of the same name, AR Kane’s ‘Love From Outer Space’, Neneh Cherry collaborators Rocketnumbernine’s moniker, ditto Andre 3000, surely a reference to Sun Ra’s ‘Disco 3000’. The man himself, however, might be dismayed that the sort of wholesale transformations of humankind which he espoused through his philosophy (which find their parallels, incidentally, in Stockhausen, who in later life also claimed to have originated from another planet) haven’t really taken. Indeed, in these fatally post-modern times, in which astronauts die of old age and decades have passed since the moon acquired new footprints, let alone Mars, his talk of cosmic exploration can seem ironically old world, like the rust accrued on decommissioned space stations. And, after all, as those bearded in one-way conversations with him in his lifetime might attest, wasn’t he a bit, you know, hatstand?

Ra’s teachings might lead nowhere but his musical example is practical, vital and of the utmost, enduring relevance. He is the Grandfather of Afro-Futurism.

There’s a tendency among white musicians and audiences to take retrospective solace in nostalgia, the halcyon days of rock and pop when they still held their innocent lustre and life was more swinging, sunny and simpler. There is a certain kind of white fan who prefers black music of a certain vintage and is uncomfortable with its present day mutations. For black musicians, black audiences, the past is not a halcyon place – it was a time of open racism, of civil rights struggles, of systematic disadvantage and everyday humiliation. Why hark back to that? The present’s not so hot either, come to think of it. The future is where it’s at, the future from which white audiences are often prone to flinch. Hence Stevie Wonder’s Arp and Moog adventures, George Clinton’s Brother From Another Planet schtick, Lee “Scratch” Perry, A Guy Called Gerald, Detroit Techno and the early embrace of Kraftwerk by African-Americans, and the whole, electric underground push of black music from Go-Go to house, hip-hop jungle to grime and footwork.

Of course, racial generalisations are never hard and fast – Ra’s music has fired up countless white rockers and left many, many black listeners cold. The singer Betty Carter once snarled that Sun Ra would get a very cold reception indeed if he dared to play in Harlem. Ultimately, however, it is a resource, an example, a metaphor for what is spatially possible in music for those of a boundless imagination.

For Sun Ra, born in a time a place when a black person was taught to expect to amount to no more than nothing, his philosophy, as successfully realised in his music, was a triumph. He saw that history was just his story – that black people could lay claim to a past heritage, even a mythical one, and, it followed, lay claim to the future. Along came Ra and so it came to pass. New worlds in his music await the unborn.

“Today is the shadow of tomorrow

Today is the present future of yesterday

Yesterday is the shadow of today

The darkness of the past is yesterday

. . . .

Yesterday belongs to the dead

Because the dead belongs to the past.

The past us yesterday.” – Sun Ra, 1958

The Sun Ra Arkestra under the direction of Marshall Allen and John Sinclair perform at the Barbican on Saturday May 31. More details here There’s then a Sun Ra residency at Cafe Oto throughout June, more info on that here