The British: so proud, yet so eager to serve. Nothing’s ever going to change, except to get worse. And I can’t leave.

You’ll have noticed this Britpop anniversary, I suppose? Everywhere you look, greybeards reminiscing; all those bastards you thought you’d seen the last of, tunnelling out of the boneyard. This was their moment, this was their time, and no miserable motherfucker’s going to take that away from them (I’d like to see them try).

The media’s been full of it, but then it always was. They pretty much control the media now, that Britpop generation – these are the new baby boomers, second-rate and shallow like the times. And this is how the glorious anniversary has been celebrated: all the usual bores, saying all the usual boring things. And I mean… just listen to them. A voice on the radio telling me that Britpop’s commercial success, and its prominence in the media, was "youth culture winning". Seriously – youth culture winning. They actually said that! In 2014! You have to stop and scratch your head: how could anyone possibly think that? How is it conceivable that anyone who was actually there, who saw this shit unfold, and saw what happened next, could still be splashing around so far from the truth – even from anything which sounds like the truth? Youth culture winning! What the fuck?

I can take this kind of ahistorical crap from the bands. If you ask someone who spent the mid-1990s guzzling cocaine and alcopops, sleeping with teenage girls in tennis skirts and being told they were the fucking king, then yes, they’re going to say that Britpop was "really exciting… an amazing time". You’d hope so, wouldn’t you? What I do find worrying, if not surprising, is this blithe miswriting – by people who should know better – of what was, for mostly unhappy reasons, a crucially important part of British cultural history.

But all those nodding dogs with fuck all to say, they’re the "experts" now. The simplistic, smugly flippant nature of what passes for media commentary on popular culture is testament to that. Everyone else is excluded from the discourse, because God damn it, they complicate things.

"Who would want a simpler history of of a dead cultural moment?" asks the protagonist of Phonogram: Rue Britannia, Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie’s fantastical comic about Britpop survivors. And the answer? Those who stand to profit in some way from this kind of negationism – Britpop’s permanent lowering of the bar has been extremely good to them, so the myth must be perpetuated. And those who, for reasons of their own, cannot permit themselves to take a wider view.

Here’s a wider view: Britpop was the willing soundtrack to – and yes, enabler of – the final destruction of everything Britpop ever claimed to love. All the glories of its precious 1960s; the idea of "youth culture" being something more than swank and competitive consumption. It managed this by posing as vital while systematically stripping away whatever made British pop music interesting or valuable, syncing with ruinous cultural trends and then, with its preposterous bulk, blotting out the sun. Worse, it left an indelible mark on millions of young white middle-class men – which in cultural terms, alas, is as good as poisoning a reservoir. Damn right we’re still suffering now. And these are Britpop’s deep dark secrets, rarely told, because history is written by the winners, who saw nothing: all the important stuff was happening in the cloud of dust behind them.

This is not the story of how Britpop "made us proud to be British again". This is not about Alex James curdling cheese and writing a column for The Sun, or two million people on the telephone trying to make credit card bookings for a monstro-gig in someone’s country estate. This is the other Britpop story, the one where Britpop steps on a rake and helps to destroy the post-war consensus. This is the one where Britpop looks at its watch while holding a glass of milk, and helps sink British popular culture in a mire of apathetic infantilism from which it has yet to emerge. The one where Britpop, trying to be nice, prepares the ground for a pop scene where the children of the landed gentry trill bucolic bollocks while the rest of us survive on long, long, piss-wet streets of chicken shops and Poundlands and closed-down fire stations, breathing in spores in rented bathrooms, stuffing ourselves with Mr Mash and a source of phenylalanine, knowing we’re probably going to die somewhere that’s even worse than this.

Britpop was about the end of the 20th century, and most of what was good in it. About the end of whatever was left of a counterculture; about the beginning of a kind of counter-counterculture which swims with the tide but faster, preening and ignorant, getting what it wants with snark and the threat of humiliation. About the beginning of – or at least a sharp acceleration in – the dumbing-down and depoliticisation of what used to be known as "alternative" culture; a sudden aversion to principle, and a redefinition of the word success. About the beginning of self-righteous privilege, the demonisation of the working class, the full assimilation of mass art into neoliberalism; the sacking of Bohemia, and the last collapse of hope. The beginning of the end. The beginning of now.

This is not about youth culture winning.

Britpop was never really about Britain, anyway, was it? It was about London. More specifically, it was about London as seen through the eyes of new arrivals, because most of those bands had recently relocated in order to seek their fortunes. And no wonder they were giddy: London was still a city of people, still wide open, still astir. It was here if you wanted it; it was what you made of it. Twenty years later, it’s well on its way to becoming a dead city, culturally – just another rich-kids’ romper room, like Paris or Manhattan. Anyone not gainfully employed in the manufacture of human misery can get the fuck out, while those who stay must pay for the purchase of water cannons, meant for them, in case they have too much to say for themselves.

Britpop didn’t make this happen, but it didn’t do nothing. It did worse than nothing.

What was actually happening here, while it was being celebrated? Camden Town – Britpop’s spiritual home – abandoned its radical bohemian past to become a millionaire-owned, tourist-oriented pop-cultural charnel house. Tony Blair – Britpop’s spiritual leader – institutionalised and extended Thatcherism and, while glad-handing gullible rockers and beaming about Britain’s marvellous musical heritage, tore up the fucking tracks.

Britpop didn’t make this happen, but it didn’t do nothing. It did worse than nothing.

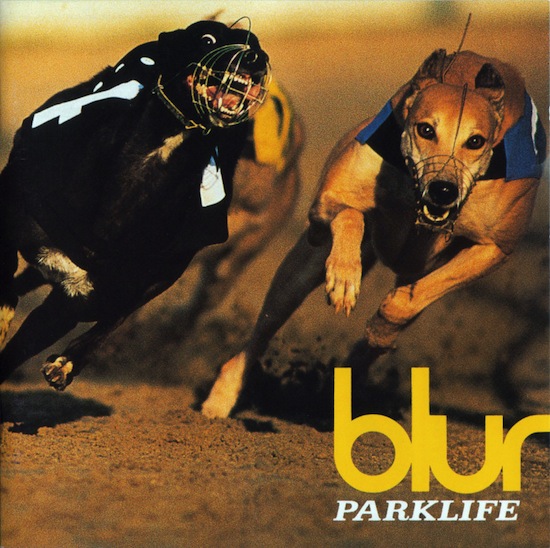

On the back cover of Parklife, Blur pretend to enjoy themselves at the dog track: this is Walthamstow Stadium, all lit up and buzzing with life. Back then, the presence of well-spoken, shiny-haired young artist types in Walthamstow was a novel and faintly humorous idea. These days, as the working class residents of "Awesomestow" are forced from their homes to the winsome sound of ukeleles, there’s not so much laughter – except from estate agents and buy-to-let landlords, who are in fucking hysterics. And in case you’re interested, the stadium closed in 2008.

Yes of course, Blur’s artistic gentrification was a stunt, a gimmick – just a bit of fun. The problem is that things feed into other things; culture is made up of a million tiny ideas, and when too many of them move in one direction, the current can sweep things away. Parklife is ahead of its time in at least one sense: dehumanisation. That is to say, the conversion of people’s lives into remote cartoons, where things go boom but it doesn’t really matter. Just like those now profiting from the breaking up of London – buying and selling what used to be called "homes" but which are now called "property" – the worst songs on Parklife are weirdly oblivious to the smell of death: the death of London, the death of Britain, the death of culture.

Parklife‘s just an old pop record, sure, but it’s on the wrong side of history, and these days it sounds heartless and sour. It didn’t make this happen, but please understand – it didn’t do nothing. It did far worse than nothing.

We need to take a closer look at the 1990s, if any of this is going to make any sense.

Less than a minute into Parklife, Damon Albarn sings "love in the ninetieeeeees" – but he’s not actually saying anything in particular about the decade he’s in. It’s just a kind of celebratory time-check: he’s reminding himself, and us, that it’s no longer the 80s.

This fact, that it was no longer the 80s, was extraordinarily important to Britpop. Nobody liked the 80s – it was all hairspray and Thatcherism, wasn’t it? Well, no… but some way into the new decade, that was still how it seemed. Certainly, for many years, most of the music was still too toxic even to be handled with irony-gloves: the 80s styles pastiched on Parklife are sealed in tanks, held up with tongs.

It seems funny nowadays, when one decade just kind of bleeds into the next, but the sheer relief with which the pop world greeted 1990 bordered on embarrassing (the NME published an overview of the last ten years in their 1989 Christmas issue, and titled it "The Eighties: Thank God It’s Over"). A lot of this sudden buoyancy would have been from Ecstasy, of course – still, there was also a genuine sense of optimism in the real world, for a couple of years at least. The fall of Communism, the crumbling of apartheid, the touchingly naïve idea that governments would get to grips with impending ecological crisis… you remember, all that stuff. The End Of History. People believed it. No one would ever go hungry again in this wonderworld of peace and prosperity.

The trouble with optimism, of course, is that it’s rather close to complacency.

What really happened in the 1990s was that one side stopped pushing. By 1994, it was rather uncool to be bothered about anything much. A whole generation playing dumb? Dunno what you’re on about, mate. Cheery sexism? Shut up love, it’s only a bit of fun. The armour-plated smugness of a new liberal bourgeoisie? Chill out you knobhead – have another line. Meanwhile, the other side were busy consolidating all the gains of the hated 80s, privatising and deregulating, getting ready to take this shit to the next level, unopposed. What did the heroes of Britpop have to say about that? Bupkis at best.

(Then again, none of these fuckers had much to say about anything, did they? Interviews with bands became a chore to read, and a trial to conduct. Britpop’s idea of an "outrageous" "bigmouth" was Louise Wener – Louise Wener! Does anyone remember a single one of her "controversial" "outbursts"? Please don’t remind me, if you do.)

Britpop had no vision, no sense of what the 1990s were, or could be – all it ever seemed to do was define itself against the previous decade, and look back to the last time things seemed bright and clear: the 1960s. (Sure, there was a wing of Britpop keener on the late 70s, bursting veins to sound exactly the same as Wire on Chairs Missing, but without the most interesting bits. Still, the impulse was the same, to recreate a Golden Age… they were just on different drugs, or something.)

This was a rather silly, selfish kind of 60s revivalism, though – a dream of being surrounded by dolly birds down at the Scotch of St James. No one seemed to have any particular interest in anything else from the time: new freedoms, new kinds of consciousness, new worlds of radical thought. No one seemed too bothered about rolling back that thick custard-skin of 80s materialism or, y’know, trying to learn something.

And while I can certainly recall a lot of people behaving like kids, I don’t think this was in the hope of recapturing the clear perspective of childhood, that one’s soul might breathe again – how charmingly un-90s is the hopeful sweetness of this contraption, designed by Damon Albarn’s dad:

Even so, this constant referencing back to the 60s did begin to creep beyond the music and the clothes, into slang (everyone was "man" again), football ("thirty years of hurt") and parliamentary politics. This inability to process the present is how Britpop managed to miss what was really going on in the Labour Party – plans being laid for an eternal 80s – and why it chose to cheerlead Blair to power not with reservations but with raised thumbs, as though expecting him to renationalise Thomas Cook and put Tony Benn back in charge of the stamps.

Damon, to his credit, saw through Blair almost at once, and turned down all the invitations to his squalid little photo-ops. Others were rather less alert. Still, the 1990s was the last time it was just assumed that anyone involved in the arts would loathe and despise the Conservative Party, a baseline of awareness and decency. This was the last time pop musicians from privileged backgrounds were expected to play it down, or make a joke of it, rather than become defensive about the "prejudice" they faced. This was the last time bands – most bands – had any objection to flogging themselves and their music off to the advertising industry, or the vaguest idea how anyone could possibly object to that. Asked in a recent tQ interview why he’d sold ‘The Universal’ – probably his loveliest song – to British Gas, Damon Albarn shrugged. "The music industry has changed… I mean, there are very few people that consider not having their music put out in that way these days."

Yeah, it’s changed all right, and the change began in 1994. Britpop was the first "alternative" style to be judged on what it sold, and was only too happy for things be this way – which led to a huge shift in priorities, both in British music and in the media which covered it (Britpop may have had no direct effect on non-white, non-guitary, non-commercial styles, but it had the fairly significant indirect effect of further marginalising them). Innovation became an irrelevance, or worse – seen as the preserve of some kind of notional nerd in a box room full of hard sums and crispy tissues. The oppositional impulse which had always driven independent music in Britain, however distantly, was gone – and in its place a kind of superconformism, a conventional ambition.

And so we all had a jolly good time, and we all got fucking screwed.

The funny thing is, at the start of 1994 it seemed like Blur had pretty much had it. Modern Life Is Rubbish, the album on which they’d tried to reinvent themselves as puckish art-school satirists, hadn’t exactly flopped, but had swayed a little in the breeze. The general feeling was that they’d been aced out by Suede, then flaming hot, still in that early, quite-exciting phase of lush and spiky songs about getting bummed by a dog on UHU. Blur, by comparison, were tat; old hat. The singles from Modern Life, even the properly gorgeous ‘For Tomorrow’, had gone almost nowhere. Live appearances would often degenerate into sad, drunken thrashing. It was a surprise to everyone (except maybe those who understood the power of PR) when ‘Girls And Boys’, the lead-off single from Parklife, hurled them back into the fray.

And for a while I really tried to be optimistic about Blur. Clearly, they could bash out a decent tune, and at least they had a bit of… I dunno, something. They’d made an effort. So, for this first listen to Parklife in nearly two decades, I’m trying to forget what I always tried to forget: the bumptiousness, the chuckling condescension… the Blurriness, basically. But you know what? It’s unavoidable. The young Damon Albarn, all jazz hands and puppy-dog eyes, is still phenomenally hard to stomach. The music is solid and reasonably well-performed, but it’s infuriatingly bubbly, you know what I mean? Some of Parklife is pretty good. Bits of it are really good. Still, I’ve found myself playing it quietly, in case the neighbours hear.

I mean, anyone who can’t see that Blur were a talented band – far more talented than most of their Britpop peers – doesn’t really understand music. This is an accomplished record: Blur’s attention to detail, and their smooth command of all those little turns and tricks which make mid-60s, late-70s and early-80s music sound the way it does… you can only admire that. But that’s the problem. You can only admire that. ‘Girls And Boys’ – with its jolly lyrics about working class people being a "herd" – starts things off with much vim and vigour, and it’s a catchy little number, but at no point does it feel like anything more than a musical prank. It’s as affecting as watching an intermediate level card trick.

‘Tracy Jacks’ has a go at being The Kinks, with a pleasing arrangement of Jam guitars, Beatley bass and Bowie strings – but it’s so… blank? Uncaring? Smug? Its suburban fairy tale is neither believable, funny nor in any way instructive. All it says is "LOOK!" – with eyeballs drawn in the Os – "We’re telling stories about middle class suburban folk, just like The Kinks!" It’s impossible to care. Part of me thinks that may have been the point. ‘End Of A Century’, full of unfocused allusions to middle age and domesticity, is another squandered chance to say something which might have been worth saying, or hearing. Still, its beautiful tune and rather hypnotic faux-communality stop you from worrying too much about that, which is nice I suppose, if vaguely sinister.

Then along comes ‘Parklife’, the song: cutting bingo tax and beer duty to help hard-working people do more of the things they enjoy. If there’s one thing that leaps out from Parklife, the album, it’s this penchant for smirking caricatures of working class culture, which probably seemed like a laugh at the time, but does expose the album’s total lack of anything resembling a heart. You wouldn’t call it class hatred, but it’s like the "affectionate" mockery of some cunt in an office who just won’t stop. I mean, ‘Bank Holiday’ – is this supposed to be funny or something? Because it fucking isn’t, it’s horrendous: a massive, grinning, lagery piss from a private jet into someone’s rockery. It’s not even offensive – it’s just a shitter version of this:

…except it’s selling something even more unhealthy.

‘Badhead’ is the first song on Parklife that’s unreservedly lovely, but as tQ’s Luke Turner so wisely said a couple of weeks back, you can’t trust a band whose best songs are their ballads. After this comes ‘The Debt Collector’, parping pointless filler. By 1994, CD was established as the primary format for pop music, and everyone’s albums began to expand to fill the available space. In the 60s bands had no choice but to pad their albums with this kind of dross, because they were churning out two of them a year. By the mid-90s, one album every twelve months was considered fast work, yet still we had to suffer through these silly instrumentals, weak attempts to be comical, songs with the bassist singing – the kind of bilge which should, at best, have been pumped off as B-sides (and there was a knock-on effect: have you heard the B-sides of the singles from Parklife? I have, twenty years ago. Once each. I’ve not quite recovered). So the first half ends with ‘Far Out’, an uninspired if pretty well-observed Syd Barrett pastiche. But there we are: a Syd Barrett pastiche. Syd Barrett, composer of some of the most unnervingly beautiful, strangely affecting music in history. Pastiched. Welcome to the 90s.

But then ‘To The End’ starts up, reminding you that this is not a bunch of no-mark pissheads, this is a band with real ability, genuine possibilities… so you hate them even more. ‘To The End’ still sounds fantastic, a perfect balance between knowingness and wide-eyed emotion. It’s a grown-up pop song that swoons. This is what Britpop should have been: expansive, inclusive, genuinely clever.

Parklife goes a bit dry after that. If I remember rightly, they caught a bit of stick for ‘Magic America’, as though it were a coherent comment on Atlanticism, or the lure of the New World for British proles, or the British longing for elsewhere… or something. Listening now, it’s hard to see why anyone ever considered it worthy of comment (compare this to the subtlety, warmth and vision of The Kinks’ ‘Australia’, if once more you want to know what Britpop could and should have been).

Nothing else is worth a light until we get to the big finish: ‘This Is A Low’ is a very fine piece of music, but even here you can’t help feeling there’s something important missing. Albarn’s clever-but-stupid lyrics are horribly grating, less like social comment than the scribblings of an advertising copywriter coming down off an E. Like the rest of Parklife, ‘This Is A Low’ makes a very big show of saying something, and says nothing at all.

There were two Britpops, really. One was spellbound, one triumphalist; one was curious, one incurious; one was a door in a wall, and the other was rock. Do you remember?

At first, what they started calling Britpop wasn’t a movement, or a scene, just the kind of flip from one thing to another which used to happen all the time in music, and doesn’t, really, now. It felt inevitable: something bright and sharp to pierce the shoegazing fog, to hack away the dreadlock fuzz of The Levellers, The Wonder Stuff and Ned’s Atomic Dustbin – all that fucking juggler shit. After that, this was like a spring morning (the idea that Britpop was a patriotic reaction to grunge is revisionism, I think, largely down to that infamous issue of Select magazine with "Yanks Go Home!" and the Union Jack on the front; back then, this stuff seemed more like a reaction against recent British music, which had been dreadful, rather than Nirvana, who everybody liked).

Anyway: Suede, Saint Etienne, Pulp, The Auteurs, Denim… you could even include the young Manic Street Preachers, maybe… none of these groups had much in common but their overt Britishness (when "Britishness", in pop and in life, meant something slightly different) and a sort of detached intelligence. They had a couple of minor hits, Suede even made the Top Ten, but there was certainly no bandwagon at this point. For a couple of years this stuff was just there, another chocolate in the box, co-existing happily with the other trends in white kids’ music: Riot Grrl, the New Wave Of New Wave, other crap which even I’ve forgotten.

Much of what was good about this music was lost in the subsequent deluge. All those rotten bands you think of when you hear the word "Britpop" – Sleeper, Echobelly, Bluetones, Thurman, Shed fuckin’ Seven and so on, and so on – they were following on from these bands, like rising damp follows on from a rainstorm. The difference was that they were regressive, seemingly informed by an incredibly limited range of very conventional influences (all Smiths and Stone Roses). This was not purism, simply a narrow horizon, British indie’s notorious aversion to anything too fast, too slow, too weird, too dirty or too disturbing.

The second Britpop, which came slightly later, was all about Oasis – or rather, everything that was bad about Oasis: slow motion guitar solos, drummers who sounded like their shoes were wet, untucked Ben Shermans flapping around like the mainsail in a westerly. People with such little sense of their own ridiculousness, they’d actually call an album Urban Hymns. Jesus Christ! We needn’t dwell. We know what Kula Shaker were all about (and if you don’t… well, never mind). We don’t need to talk about the Stereophonics, or Ocean Colour Scene. No mythology to puncture here. 1996: The Year Of The Rat.

Oasis themselves I thought were OK, so sue me. I was never fond of what the NME in 2012 – with a straight face, I swear! – called "Noel Gallagher’s no-nonsense lyrics", but when you forgot that saviours-of-British-rock baloney, they weren’t so bad. Unbelievably empty, yes, and stupid? Oh, you bet. But there’s something to be said for this kind of obliterative, almost transcendent stupidity (the irony being that in real life, Noel Gallagher is one of the sharpest and funniest bastards you ever could hope to meet). What was so pernicious here was not so much the music but the idea of Oasis: doughty English knights on horseback, come to rescue pop from all that poofy art-school shit.

It didn’t have to be that way. Believe it or not, on their earliest demos Oasis covered ‘Feel The Groove’ by Cartouche, an early-90s Euro dance act (presumably named after the sound of a brick being thrown into a river). This was not some kind of piss-take. Noel had spotted the connection between its nursery-rhyme relentlessness and his own simplistic style, and – perhaps for the last time ever – chose to do something unexpected. Sure, the result is not very good, but it suggests what might have been: an Oasis open to suggestion, willing to let in some light. But of course, for whatever reason, this approach was dropped. No one would be feeling any grooves from now on – just a kind of sodden thud. And in their enormity, Oasis could have done anything they liked. Instead: a whole new world of grey, the most disastrous misunderstanding of The Beatles since Charles Manson.

Although the thing is, Oasis didn’t sound like The Beatles, did they? Everyone knows they stole it all from Kipper.

Parklife, for me – and I may be alone on this – is wedged in the hinge where these two Britpops meet. At that time, the "middle class", "arty" Blur were seen as the natural, implacable enemies of rough, tough Oasis – the Jocks and the Geordies, Bully Beef and Chips. Seen from higher ground, of course, it’s not like that at all. When you listen, rather than look, Blur’s mid-90s music feels like a missing link between the postmodern glimmer of ‘Avenue’ or ‘Razzmatazz’ and the bulldozing gibberish of ‘Roll With It’. Parklife self-identifies as "clever", but it’s a significant step away from proto-Britpop, which had been for the most part highly personalised and esoteric, and semi-commercial at best with its dizzying eclecticism (Saint Etienne) or showy perversity (Suede). Parklife is a rock record. Parklife isn’t about ideas, it’s about suggestion: the suggestion of relevance, of something where there’s really nothing. Parklife is solid, expensive-sounding and tooled for mainstream appeal. Parklife might come on like some kind of concept album about English proletarian culture (or something), but its lyrics skid over the top of meaning, always vague enough to be ignored. Its "cleverness" is a clever illusion.

Parklife – and this is the best thing about it – wasn’t scared of becoming popular.

Parklife – and this is the worst thing about it – soon became very popular indeed.

Low rents and high living; devastating personal problems; out in Camden every night, tight as a boiled owl.

Yeah, I remember it well. From 1993 until the start of 1998, I was working for Melody Maker, what we used to call a "music paper", even though we knew that it was really an indie rock paper – more open-minded than that might suggest, but still lashed to a student audience who wouldn’t buy anything with black people on the cover, and whose ideas about "real music" were as stubborn and stunted as old-time religion. This could sometimes be restricting for those of us whose tastes did not generally run to indie rock, but you know, we managed – you could always pitch for that week’s token feature on something else: electronica, chart pop, hip hop or something a little bit avant-garde. Besides, they let us write about music as though it mattered, which was why we were there. We could make a modest living from it, too, in the days when you could rent a bedsit in Holloway for fifty-five pounds a week.

But the music press was changing – or to put it another way, dying. The story you most commonly hear is that it became a victim of Britpop’s sudden success, as the bands it covered got so big that they could be followed in the daily papers and on television, until there was no real need for a weekly music paper. Which suggests that all anyone wanted from a music paper in the first place was the kind of coverage you’d find in the daily papers, or on television. That’s complete nonsense – for one thing, sales went up as Britpop rose – but the wrong people seemed to believe it, and the papers changed in tone.

This was maybe music writing’s last chance to reach a mass readership, and do what it was meant to do: circulate some bright ideas, awaken sensibilities, encourage innovation. Britpop is what happened instead. And not by mistake – the press went chasing after that shiny bauble as fast as any loser band. And it was so fucking gleeful. Word counts were cut; analysis gave way to mindless boosterism. I remember an NME Glastonbury supplement claiming that Sleeper were "driven by an obsessive hatred of mediocrity at all levels". It was beyond parody. I remember gasping in horrified disbelief, again and again, at decisions being made around me. Looking back – and it’s not often I say this of my younger self – I was absolutely right (though not wholly innocent, I’ll admit, in case anyone has back issues to hand). If anything, it was this abrupt shift in the tone of music writing, this kind of failed populism, which led casual readers to decide they could get all this elsewhere. And certainly, it drove away the hardcore.

Orgasms were being faked all over the place, as well. Looking back, Britpop is almost unique among those musical trends which lasted half a decade or more, in that you couldn’t fill a Nuggets-type compilation with genuinely good tracks. Trying to find twenty memorable singles from twenty different Britpop bands, you’d end up on the very fringes of what anybody ever meant by "Britpop": ‘Get Yourself Together’ by Velocette? Possibly. ‘CF Kane’ by Delicatessen? No, no, they were something else. And these differences matter, as much as any of this rubbish matters.

Even in the high Britpop summer of 1995, I’d crawl home and listen to Joni Mitchell, Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, Fleetwood Mac… or else the eerie delirium of pirate stations playing music which sounded like now, but which I never wrote about because (thank God!) I didn’t understand it, so I couldn’t explain it. So it couldn’t bore me rigid.

And when I look at the records from that period which I bothered to keep – a few albums by The Boo Radleys, the first one by Supergrass, one or two more – they’re genuinely good, but I can’t imagine really wanting to listen to them any time soon. Tainted by association? It wouldn’t surprise me: even Pulp, who would have been a superb band in any era, have been folded in with their peers, at least in the popular consciousness. From the BBC’s recent Britpop splurge, here’s Steve Lamacq on ‘Common People’: "It is one of the defining records of Britpop because it seemed to embrace the essence of the time so perfectly… it seemed to sum up a feeling of ‘us and them’, as if to illustrate how the indie mavericks had taken on the pop stars and – for once – they’d won."

Again with this victory stuff! Now look – I think Steve Lamacq’s okay. Yeah, most of the music he likes is shit, but he’s the real thing; a true rock and roller in his way. He genuinely loves and understands that terrible music, so hey… I don’t want to put him down. But this was a ludicrous thing to say, and what troubles me most is that I’m pretty sure it’s a fairly mainstream view. In fact, ‘Common People’ is the one explicitly oppositional pop single of the Britpop era, and as such it doesn’t "define" a bloody thing – besides, in what sense is that song about winning? As for this "feeling of us and them", damn right I had a feeling of "us and them" in 1995 – and even more so now – but I’m not sure Steve and I would quite agree on the specifics. Also: "indie mavericks"? Cast? Powder? Gene?

I remember this kind of triumphalism from the time. It was creepy then, and sounds a whole lot creepier today. But it was enforced so strictly: I remember being chided by members of my editorial staff for scoffing at "what the kids are into", and was told in no uncertain terms that I should stop pointing out the lack of imagination in this music, the way so much of it was blatantly, unavoidably second-rate. "The kids haven’t heard this kind of music before," I was assured. "It’s all new to them." In other words, don’t be a prick – don’t worry yourself about cultural death. We’re providing a service here. Things were changing. They really were.

(Not that the music press, as we understood it, would have to worry much longer. Shortly after the release of Parklife, our front page trailed a feature on some nerdy new computer thing which was just getting big in the States. INSIDE THE INFONET, it said. "Eh? What?" spluttered a reddening face in the Tuesday editorial meeting. "It’s called the Infonet, isn’t it? Isn’t it?" For a music weekly in 1994, this was a faux pas roughly comparable to spotting a cowled, scythe-swinging figure coming up the garden path, and announcing the imminent arrival of the Grim Peeper. Oh, how we laughed.)

So, as Blur and Oasis battled it out for number one – with singles that were almost supernaturally shit – everyone was informed that this was terribly important. Yeah, it’s nice when a band you like does well. But no, this was more than that – this was really important. At the time, other kinds of music were having laws made against them, or having their venues closed. But this? This was important.

Why? Because the mainstream media was staffed by baby boomers, who still thought in terms of "bands". It’s "bands" that make the real music, right? "The music industry hasn’t seen anything like it since The Beatles fought it out with The Rolling Stones in the 60s," said John Humphrys on the BBC News – and right there it was abundantly clear why this had gone mainstream, and was going to stay there (although… listen to how he spits out the phrase "pop groups", as though it’s in inverted commas: in that great millennial shift from the stuffiness of the old Establishment to the pseudo-hip inverted entryism which they favour today, this might just be the exact point of transference).

Anyway, Britpop fell for it. The fact that a pig like Humphrys was on the telly talking about "us" was meant to add some kind of legitimacy – "we" were going big-time. British guitar bands, raised on film of The Beatles waving from jumbo jets, had been grumpy for years about their lack of chart success. This kind of music used to sell millions, so why didn’t it now? (There was no point answering that question, because they didn’t want to hear the answer, and may not have understood it.) No surprise that their response to all this attention was to make like the nouveau riche, snatching all the tokens of mainstream success. Such was the broken logic of Britpop: if the Establishment is bigging you up, that means you pose a threat to the Establishment. If they put you on the one o’clock news – even if they use the same droll tone as on that story about the windsurfing panda – celebrate, boy. It means you’ve won.

Britpop’s sudden, shattering success created an orthodoxy overnight. Even at the time, it was depressingly obvious that this was going to shut down British guitar music, creatively, for a long time to come. It was the perfect inversion of punk: a giant contraction, a kind of implosion, British guitar pop collapsing in on itself so tightly that nothing could get in or out, for years and years and years.

And so today, British guitar pop looks and sounds like what it is: the product of twenty years of inbreeding. Undersized, genetically disordered, sterile. The end of the line.

OK, there’s really no such thing as originality in pop – only people ripping off stuff that you haven’t heard yet – but let’s face it, Britpop was ridiculous. This could not even pass itself off as postmodernism: there was nothing bold about it, no sense of adventure in amongst the ruins and the masks. This was the bourgeois aesthetic in sound, a musical equivalent of mock-tudor houses and crap from the Franklin Mint. A careful but fundamentally clueless reshuffling of bits of the past with no real grasp of what went where, or what meant what… just that prissy preoccupation with "good taste" which leads, unfailingly, to utter fucking ghastliness.

Britpop wasn’t just derivative; there was a palpable fear of innovation. In the 1990s, music technology was developing faster than at any point since the days of Jim Marshall, but these bozos wouldn’t budge from the same old harmonies, the same old riffs. All the while completely unaware that this was not in fact continuing a grand tradition – rather, desecrating it. All of Britpop’s supposed affection for post-war British life, its vaguely-stated aim to "protect" this stuff from "Americanisation"… it was so much mince. This was only ever about the clothes, or some shit they’d seen on TV; Damon Albarn, asked for an example of the "loss of identity" which troubled him so, could only think of the horse brasses being taken down in his local pub.

What these people failed to understand was the forward-looking nature of this particular past, its openness to outside influence, its self-conscious modernity… how un-British it was, in a sense. But when you have no vision, you will misinterpret the past as badly as the present, and you cannot be trusted with the future.

Living At Thamesmead (1974)

So, in the summer of 1996 I went to see Oasis at Knebworth. Standing in the mellow sunshine, surrounded by kids who seemed genuinely moved when Noel announced that as the largest audience ever to pay to get into a rock gig, they were "making history", I tried to make sense of what the hell was going on. In the end, I had to do exactly what Oasis wanted me to do – that is, stop thinking. Instantly, everything made perfect sense… it wasn’t good, but it did make sense. I was struck by an almost unbearable poignancy; I wrote my review in a kind of melancholy daze. Our generation was fucked, I said – bullshitters, wasters. "Still, we had something. At some point, we had the time of our lives."

And that was it, wasn’t it? That was really it. Maybe this is why most of the time I don’t like to think too much about Britpop – aside from the fact that most of it was shit. It’s a reminder of the strength and pain of being young; that it can’t come again. For those borne to a comfortable place on the cultural currents of Britpop, it’s a fond memory, something worth celebrating. I disagree… and because I’m not the only one whose life, in the end, was somehow diminished by Britpop, and Blair, and the 19-fucking-90s, I don’t think it’s just me. But still… at some point, I had the time of my life.

If you really want to know about Britpop, take a look at how it ended. More than once I’ve seen the death of Princess Diana in August 1997 described as "the end of Britpop"; our generation’s Altamont, right? This used to make me howl with laughter, but you know, the more I think about it… no, seriously. In a way.

Britpop and the cult of Diana shared the same root, after all: a forced exceptionalism, rooted in pride but also desperation. Maybe this was the day when Britpop finally merged with the mainstream, and the two could not be told apart. Sentimental populism, anti-intellectualism, enforced with a false communion. Radio One replaced its scheduled programmes with a kind of moping mixtape, so its target demographic had to give a toss. Apparently, many of them did. So much for "Cool Britannia" – the only kind of glamour which really resonates with the British is what Tom Nairn in his study of the monarchy, The Enchanted Glass, called "The Glamour of Backwardness". It’s like a fucking spell.

So the same old hacks who’d been so pleased to tell the world how London was swinging again ran back to their Apple Macs, to determine what this flood of tears and snot and uncomprehending emotion said about "us as a nation". Few reached the same conclusions as me, and everyone I knew, which was strange, because they seemed so very obvious: Britain would never grow up. Britain, with its stiff upper lip gone slack, was now a blubbering baby. Britain had missed what may have been its last chance to change. The 90s were a turning point, possibilites spread like a fan of cards… and Britain came out of it dumber, more pliant, more boastfully backward than ever.

The flag-waving’s for real now. And it’s what it always is – a sign of insecurity – but within that is a terrible kind of strength. In the confusion of austerity a brand new Britishness is afoot, like the old one but fractionally closer to fascism. More than apolitical – actively hostile to radical thought. More than dismissive of class-consciousness – angry at the slightest suggestion that anyone’s problem might not be a problem with them, but a problem with Britain. It’s everywhere. And every single chance it gets, it guts that "other" Britishness, the kind pop music once personified, the kind that’s all about irreverence, vitality and wit. Not just in the present, but retrospectively – watch now, as history slowly changes; watch the life and meaning being sucked from everything good that ever emerged from this island, starting with Britpop pin-up boys like The Beatles, The Smiths, the Sex Pistols… all that love and scorn wiped from the past, and therefore from the future.

Yes of course, if you scratch around a bit, this other Britishness is still there, not least in pop music – in styles too far underground to "matter", in the occasional chart hit, in the sarcasm and brutality of Sleaford Mods or Fat White Family. But it feels like a losing battle. Everything let loose by Britpop – that vague jingoism, that false sense of community, that distrust of seriousness, that come-on-mate-don’t-be-a-fucking-misery pseudo-celebratory shit… it was all a bit too close to what Britain has always done a bit too well. Is anybody really surprised that the wrong people sensed this, picked it up and ran with it – or that a kind of aggressive complacency turned out to be an unwise tack, when everything was up for grabs? The architects of Britpop should be shamefaced and contrite, yet here we are at the end of a month of "celebration". Congratulations.

So proud, yet so eager to serve. Nothing’s ever going to change, except to get worse. And I can’t leave. I can never leave. None of us can ever leave.