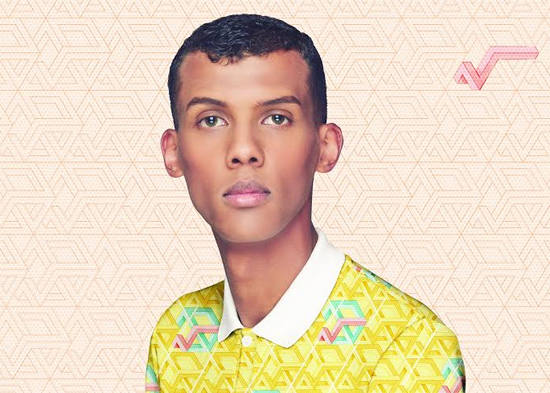

Stromae is Europe’s biggest popstar right now, and what’s more he’s almost certainly its most unusual, and not just because he’s Belgian. His story is as strange and enchanting as his gazelle-like 6 ft 5 frame, usually clothed in subtle monochrome beige, mustard or salmon and replete with bowtie if he’s in the mood. The alter ego of Paul Van Haver inhabits a previously unexplored hinterland where male model cheekbones coalesce with tickled funny bones, and while it’s an uneasy alliance – like some androgynous Action Man, or a Frank Spencer in busy symmetrical African textiles – it works somehow. This strident individuality is part of what has endeared him to so many beyond the confines of Flanders, Wallonia and even the far off exotic province of Luxembourg.

He seems to have appeared fully-formed from a stylishly madcap dream, as somnambulantly surreal as any René Magritte painting, and in a modern age when eccentricity is usually frowned upon by major labels, he is the very antithesis of popstar by focus group. A committee could not create somebody this sharp, this realised, so full of flair and so unlike anything else around. Ostensibly he’s a Europop artist and defiantly proud of that fact, though there’s so much more going on than meets the eye or the ear with him, and his percussive background, ability to merge genres and his effortless flow – like a Brusselian Eminem when he’s spitting angrily – means he’s surely more Euro-hop than anything. He’s as Afrobeat as he is Eurobeat, as Jacques Brel as he is Jacques Tati, as adept at stealing from working class Spanish flamenco as he is poncey French opéra comique (his big beat take on ‘Carmen’ is a masterclass in how to pilfer). He’s also not afraid to approach subjects in song that are usually off limits in the pop universe: divorce, depression, debt, death… last year The Guardian called him "the Morrissey of the Eurozone".

In France, Stromae is a megastar. Second album Racine Carrée sold more than 80,000 in its first week of release and wound up shifting more copies than Daft Punk’s Random Access Memories at the conclusion of 2013. He’s sold 1.5 million copies there alone already. Some weeks ago he was on the cover of the country’s biggest music weekly Les Inrockuptibles; the organ had proudly employed his services as rédacteur-en-chef for one week only, allowing him to big up his own favourite new artists like Benjamin Clementine and King Krule. Even the guy who cuts my hair in Paris tells me enthusiastically about how good Stromae’s lyrics are (he turns out to be a far better critic than he is a hairdresser). From Algerians to Acadians, the Francosphere continues to capitulate to his charms, but it’s not just French speakers who are tumbling helplessly into his long, outstretched arms now. In Germany and Italy he’s popular, and significantly the Netherlands is beginning to embrace him like a son. His neighbours might share the Low Countries epithet but they don’t share a language, and this is key to eventual world domination according to the team that surrounds him. Oh, and did I mention Kanye West has remixed him? Angel Haze has rapped over one of his tracks; he’s even influencing fashion in his homeland right now.

When we meet in Holland, Stromae gambols down the hall holding an MTV award in one hand and waving with the other. He’s built like a racing snake, as my father would have said, and to know him is to feel distended. His own father was tragically killed in the Rwandan genocide twenty years ago, and this absent figure from his life is explored in song, most poignantly on megahit ‘Papaoutai’ (or ‘dad, where are you?’) which is heading for 150 million YouTube views at the time of writing. Brought up by his mother alone, he’s clearly a man who was instilled with manners and taught to maintain them at all times. After shaking hands we wander into the backstage catering area where he hovers around smiling awkwardly, thanking the journalists who’ve flown in to see him and offering to pour drinks before he makes his way over to the pinball machine where he can attempt to relax for a few moments before our interview. And then it’ll almost be time to head out to the arena where he’ll not only perform, but go the extra mile by conducting much of the between song banter in Dutch. He appears to be an instinctively gracious and obliging character, and he spends much of the interview I conduct with him either thanking me or thanking anyone who shows any interest in Stromae. Even the villains.

Tonight he’s playing for 6,000 people at the Heineken Music Hall on the outskirts of Amsterdam, and in November he comes back to perform for 13,500 people. If he can break here, he can break anywhere, or at least that’s the theory. Britain has thus far refused with Faragian obstinacy to yield to pop’s poster boy for European homogeneity, but you get the impression it may not hold out for much longer, even if he maintains his bloody-minded resolution to keep singing in French. He’s already sold out the Hammersmith Apollo in December, and a rumoured spot at Glastonbury this year will do him no harm at all if it materialises, because live he’s really quite brilliant.

Though should the world as a whole fall in love with him, you do wonder how Paul Van Haver himself will deal with it. He refers to Stromae as a ‘project’ – which he says he does for his own sanity – and while he doesn’t talk about himself in the third person except when pressed to, he does talk mostly about ‘we’ instead of ‘I’, and when he’s referring to his audience he often slips into the second person which can be confusing, though this you suspect is due to English being his second or third language. At times during the interview he gets frustrated, but you sense he’s able to convey most of what he’s trying to say. In French he’s articulate, poetic and funny, so it stands to reason that he sings everything in French. And why wouldn’t he?

How are you?

Stromae: I’m fine thank you. It’s really good to ask this question. And you, how are you? Thank you for the question.

I’m good thanks, Stromae. As a Belgian, what does Amsterdam mean to you? Did you come over here as a kid on the weekends and smoke weed?

S: No. [laughs] It’s a cliche of course, and I know some friends of mine who would go to Amsterdam or Maastricht which is closer to Amsterdam for us. No, for me Amsterdam represents – and maybe it’s a little selfish to say this – proof that people can dance to non-English music even if they don’t understand the lyrics, you know what I mean? Actually it wasn’t our ambition at the outset and we didn’t believe it could be done, but the public from the very first track [‘Alors on Danse’ sold a million copies across Europe] showed us that ‘yes, while we don’t understand every word we can feel it’. And actually now it’s our conviction. Sometimes people say, ‘You are crazy because you want to sing in French in Bolivia, in England, in the US, in Japan’, but I don’t think we’re the first ones who’ve tried it, and it’s possible because we’re not really talking about languages. We’re talking about feelings and émotion. That’s all.

Édith Piaf and Jacques Brel are two artists who conveyed great emotion with some of the audiences they were singing to not knowing what any of it meant. Is that the plan then, to crack the Anglosphere? The UK, the US, maybe Australia…

S: Yes, and not only those places, we want to sing for every human actually, even if they don’t understand us. It’s not about possible or impossible, it’s just about ‘You are a human, I am a human, so we can understand each other.’ I think it is possible actually. And I think you, you the English and your music, you’ve proved that over a long period of time actually. For some people it’s the most musical of all the languages, but I don’t think that’s true actually. You’ve believed that for a long time now, and now we have to believe in our cultures too. That’s our problem, a complexe d’infériorité, you understand that? Maybe it’s the same in English. It’s part of the complexe d’infériorité to say, ‘Yeah but it’s in English so it’s easier’. Maybe it’s easier, yes, but it’s not impossible actually.

So you think everyone should sing in their own languages?

S: It’s important to keep this big patchwork that is the world and say, ‘I want to listen to Creole Portuguese and I’ll still be able to feel all the emotions and melancholy even if I don’t understand the lyrics.’ And it’s crazy, when I go to Italy people say, ‘Yeah but you have a beautiful language so it’s easier’ and I say ‘No! You have a big culture and a beautiful language in Italy too, and we need to have your point of view.’ I think that singing is just a point of view, and you have to give us your point of view and not imitate an English guy, we need your point of view and your language.

You’re really famous in Belgium now, so do you not look at London and possible excursions you might want to go on, and think you can go shopping there without getting hassled in the street? Can you leave the house in Brussels?

S: Yes I can. Maybe that’s why I’m happy to live there because there is no star system. Of course people recognise me, of course. Yesterday for instance we were in the centre of Brussels. I was a little bit afraid, because this kind of relationship with people where they say, ‘Can I take a picture with you?’ is not really normal… it’s a little bit special. At the end of the day we were just in the street having a beer and people were walking by and it was nice. I was thinking, ‘I hope it’s possible to do my job even if people recognise me, and we can just have a normal discussion with everybody.’ I think it’s possible, and I think it’s possible in every city, it just depends on how you are with the public. And perhaps that’s why I love to be so ridiculous, whether it’s singing or performing or making the worst jokes. It keeps me down to earth and says to people, ‘Okay I’m ridiculous, so we’re exactly the same.’

You must be the most famous Belgian at the moment after Tintin. Tintin, Jacques Brel, Rene Magritte, Leopold II, and then you. So perhaps you’re the fifth most famous Belgian ever.

S: Haha, well thank you, but I’m not sure.

Was that an MTV award you were carrying?

S: Yes, for best Belgian act. I’ve never received an MTV award before so it was my first one.

I’ve never seen one before, so it was my first one too. And you cleaned up at les Victoires de la Musique in France this year and you’ve been winning awards all over the place. And on top of all that, Nicolas Sarkozy is apparently a fan?

S: He said that? Okay. Thanks to him. I didn’t know.

And Jean Claude Van Damme as well.

S: He’s a fan of Jean Claude Van Damme? [Laughs] I’m a fan of Jean Claude. I don’t know if you know about Jean Claude Van Damme’s reputation, but all French people used to joke about him because he did some interviews that were a little bit ridiculous. And actually thanks to him, Belgium is now less ridiculous than before. They were saying he was more dumb than anybody else, but actually he’s just dumb like you. He has the honesty to show his ridiculous side, and I’m proud of him. I don’t know if in England you have this compulsion to show your ridiculous side; I think it’s so honest for a famous person – an actor or something – to show how ridiculous he or she really is.

You’ve done a series of "leçons insolites" [or unusual lessons] on the internet where you introduce new songs by means of a presentation in various locations, whether that be a supermarket or on a gondola. There are tonnes of them and they’re proving very popular, and I think my personal favourite is the film you made with Vincent Kompany and the Belgian World Cup Squad.

S: Thank you very much! He’s a good actor actually. He really surprised me. We thought, ‘he’s a football man, he won’t be able to act,’ but actually he was a lot better than we could have imagined.

You’ve made a lot of those videos. That was was leçon 28, right?

S: We want to continue until – I dunno – a thousand. If I’m still alive. [laughs]

Are you looking forward to the World Cup? Belgium look tasty.

S: Yes, I think we have the best defender in England, Vincent [who plays for Manchester City] in our team, and we have Eden Hazard [who plays for Chelsea] too. I’m proud of this Belgian team, so I will support them. In the Champions League it gets a bit complicated with all the players playing for different sides so maybe I’ll follow soccer like a woman. Like when it’s too complicated I don’t follow it, when it’s simple, okay fine.

Speaking of observing from a woman’s perspective, in the video for ‘Tous les mêmes’ you’re either doing an impression of Phil Oakey in the 80s, or more likely you’re playing a woman and a man at the same time.

S: It’s actually about a relationship and how a man and a woman can be so ridiculous. I wanted to show the ridiculous part of a love story, which isn’t the part we always want to show. You know the situation; for instance, when the girl says she wants to break up the relationship and she says ‘Okay, I think we have to finish’ but it’s just acting, and the boy says ‘Okay you want to finish, let’s finish’, but he’s also acting. It was a different version of a love story, and I wanted to have this half and half to also show my feminine side, and because I’m trying to talk from the perspective of a woman. Of course I can’t realise the vision precisely, of course it’s a clichéd vision of a girl. I think they’re the only two races on earth, women and men, and I wanted to represent them both.

You’re very strong visually with your own clearly defined aesthetic. So many popstars are boring now, whereas you’re not boring in the least…

S: Thank you so much, I think that’s my job. And thanks to the older generation, Brel, Aznavour, Piaf, the best lessons they gave us were to let us know our job isn’t to promote our own personal image. Of course we take pictures with people, we perform, that’s our job, but it’s not because people love us, no. People love themselves, and we are here to perform their stories. Interpreting their stories is my job.

So how close is Stromae to Paul Van Haver?

S: I think it’s a mask or something. No, maybe I think Stromae is Paul Van Haver exaggerated. Of course Paul Van Haver is the same person, but all the things I can’t do or say in my real life as Paul Van Haver I can do or say as Stromae.

You keep saying “we”. Is that some kind of Batman duality thing going on, or are you talking about the band around you, the label, the management etc?

S: That’s why I prefer to say Stromae is a project, it’s better for my brain to understate it. It’s not about me, it’s about a moment in life. Okay, people decided to choose this album, okay ‘we like this song, we like that song’, okay thank you very much, maybe the third album will be a total flop.

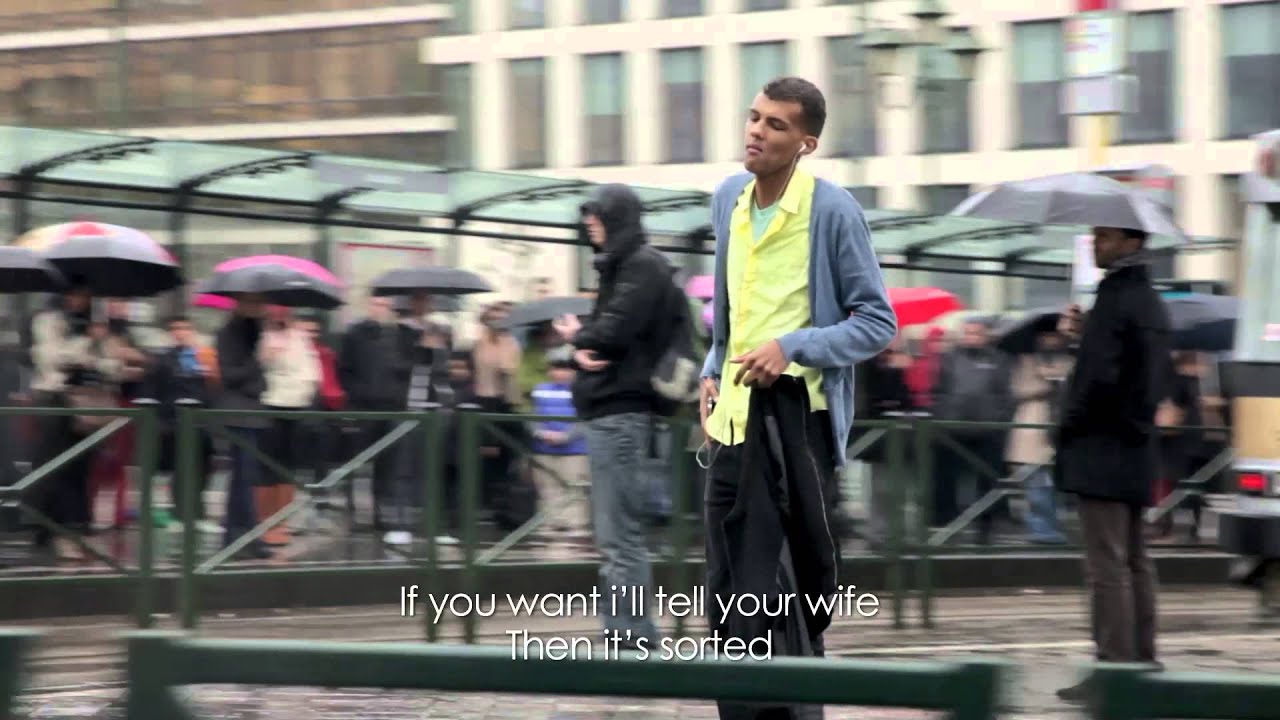

‘Formidable’ is perhaps my favourite. Is that a breakup song?

S: Mmm hmm, but it’s more about loneliness. C’est juste un prétexte [It’s just an excuse]. This guy is drunk, he’s ridiculous, but he’s just lonely and he needs a hand. The song was inspired by a homeless guy [I met] ten years ago. I was walking in the street with my then girlfriend and this guy screams at us: "Who do you think you are? Do you think you’re beautiful?" to us, that was the sentence. He was like a travesty, but the worst travesty I saw in my life, but he said ‘Do you think you’re beautiful?’ to me and my girlfriend. And I was thinking, ‘He’s right.’ I never forget the sentence – "Tu te crois beau" – and I put it in my music, "Because you’re just married and you have a baby, who do you think you are?"

‘Bâtard’ seems to be the most ferocious song on the album containing angry inner conflict. There are lines that roughly translate as ‘Whether you’re macho or homo… white trash or Paris bobo… Hutu or tutsi…’ With regards to the last one, growing up as a child in Belgium and knowing what the state and church did in Rwanda, did it make you want to rebel at all?

S: I’m not really a rebel, I’m just somebody who can’t make choices. It’s so difficult working with everybody. The running joke now is ‘Paul, take a decision!’ That’s my problem. And I don’t think I’m really that interesting. I have no conviction. My girlfriend says I have a lot of conviction but I’m not so sure. I don’t really have an opinion. I have small opinions on small things; the most interesting things I don’t have an opinion about, because it’s so difficult because everybody is involved.

Do you feel like a conduit or vessel?

S: I’m not sure but I don’t think so. I think ‘Bâtard’ is maybe it’s the most personal track on the album. In the first verse I’m talking about this extremist guy who has to choose between extremist things, and in the second verse I’m describing my personality – the guy who kind of has the choice to take a decision. And the thrust of the song is ‘Who’s better? The extremist guy or the guy who can’t make a decision?’ Actually the difference between the pair is that one has balls and the other one has no balls. It’s easy to say the extremist is the worst, but that’s not the message I’m trying to convey. It’s so easy to judge people who take decisions quickly, they have a reason to follow extremist opinions but we have to understand why they have these extremist opinions. I’m not better than them. We are exactly the same, it just depends on our conditions.

The way we’re shaped and conditioned by the circumstances around us?

S: No no no, our personal experiences. If I don’t have any money, if I’m hungry, if I can’t have any children. There is always a reason. Talk to the guy! That’s the best thing you can do. The best example I can think of – it’s not about Catholicism or anything – is where Pope Jean Paul II spoke to the guy who tried to assassinate him. I think that was the best example of maturity I can think of. And I’m not talking about religion – it’s just humane; it’s about talking with your enemy, your worst enemy.

Do you not feel any resentment towards the Catholic Church regarding the way they stirred up bad feeling in Rwanda after colonialist powers sought to exit?

S: Of course you can look at history all you want, but now it is done. Now it’s done. What do you want to do? Of course it’s easy to say ‘forgive’, and I think it’s not exactly forgiven what happened in Rwanda, but it’s impossible to punish everybody who did something wrong. Now what do you want to do, put half of the population in prison? Of course it’s not easy, and I don’t think everything is over. Talk is easy, talk is cheap. Of course you can say, ‘That is the white problem’ and ‘That is the African problem’, but what’s done is done.