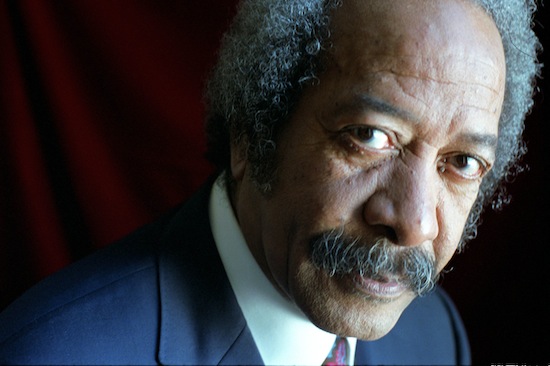

The gently spoken, immaculately dressed 76-year-old who is giving a rare interview on the eve of an even rarer London live date, doesn’t give any clue in the way he talks to the fact that he’s the closest New Orleans has to living musical royalty.

But the owner of the unfailingly polite baritone – the song-writer, producer, pianist and A&R genius, Allen Toussaint – has been a key figure in every major development in the Crescent City r&b sound for the last 50 years. In addition, he has worked with pretty much every major name in soul and funk Nawlins has produced from Lee Dorsey to Dr John, via Professor Longhair and The Meters. His list of songwriting credits is an embarrassment of riches including ‘Hercules’ for Aaron Neville, ‘Get Out Of My Life Woman’ for Lee Dorsey, ‘Mother In Law’ for Ernie K Doe, ‘Lipstick Traces’ for Benny Spellman and ‘Ruler Of My Heart’ for Irma Thomas. His songs have a peculiar immediacy and verve that have seen them be covered by the disparate likes of The Doors (‘Get Out Of My Life Woman’), The Rolling Stones (‘Fortune Teller’) and Devo (‘Working In A Coalmine’).

His industry and inventiveness made him an attractive proposition in the studio to plenty of out of town artists such as Paul McCartney, Robert Palmer, Sandy Denny, Labelle, The Pointer Sisters and Solomon Burke as well as his busy schedule with local legends. Yet it’s still fair to say that – hardcore fans of [old school] r&b notwithstanding – he was hardly a household name outside of Louisiana, pre-Katrina. (In the 1960s this in itself probably had more to do with the distribution networks of Nawlins labels, rather than any particular problems with the local r&b/funk style translating into national chart success. In addition however, as a songwriter, he often used his mother’s maiden name, Naomi Neville, in order to circumnavigate a publishing deal and his protestant work ethic on behalf of other artists meant that his own career always took second place.)

This perception has shifted somewhat over the last decade as he’s started playing live more frequently and even going on tour. He’s also no doubt been introduced to a whole new set of fans by his numerous appearances in HBO drama series Treme alongside other living legends such as Dr John and younger talents such as Kermit Ruffin.

You’re over in Europe playing what is a relatively rare series of live dates, but looking back at your touring history, it’s clear that you were a relatively late starter at playing live… in fact you only started playing live when a lot of people are thinking about cutting down on playing live or quitting altogether…

Allen Toussaint: [laughs] That’s a yes. I guess you could put it that way.

How did you start so late?

AT: Well, I never planned on being a live performer. My whole forte was about being in the studio, producing, playing the piano on recording sessions. I was all about the studio. That’s where I spent my whole life and I thought it would always be that way. This [touring] is something that came about in the aftermath of Katrina. And I have done some mini-tours since but I’ve always thought of myself as one in the background.

And when you started playing live and doing shows, what kind of perspective did it give you on music that you didn’t have before?

AT: It was wonderful, it was a blessing. In the studio you have take one, take two, take three… take twenty and you go at it and you want to still be very musical but you’re going to the painstaking trouble of getting everything correct and you’re trying to ultimately reach people. However, you’re doing it in an environment that the people who you’re trying to reach aren’t there. It’s just you and the other workers… musicians. However, when you’re playing live, those people who you’re trying to please and reach, they’re right there giving you feedback. And you don’t get that feedback in the studio. So it’s been quite rewarding since I’ve been going out playing live. It has enhanced my enthusiasm for one thing for what we do. It’s been very inspiring.

From the little I’ve learned about your childhood, it seems like you were around a lot of musicians when you were a boy and of course, you grew up in one of the most musical cities in the world. Was it always a given that you were going to go into music?

AT: Yes, always from the first touch I was hooked. Even as a very young child, I thought, ‘This is wonderful and it’s what I want to do.’ Even long before I thought about what rewards could come from it, it was reward enough just to be involved in making music.

Can you tell me how you first met Professor Longhair and describe what he was like as a piano tutor?

AT: Oh, he was a virtuoso and out on his own. You could tell that even if you didn’t meet him. But I met him as a teenager. I met him at what we used to call a ‘sock hop’. We’d hire schools to put on little dances. I was 16 when I met him for the first time but I had been listening to him since I was tot, for a long time before then. When I did meet him he was playing a Spinet piano, which was kind of short. But he was so massive in my mind, I could not believe he was playing such a small piano. And it still sounded like a whirley [Wurlitzitzer electronic piano]. I didn’t see him again until I was 18 and next time he wasn’t playing piano but working in a record shop called One Stop Record Shop on Rampart Street. I was sent to buy a recording and they didn’t have them out front so I had to go to the back of the store, and the guy who carried the records from the back of the store to the front was Professor Longhair. And when I saw him I couldn’t believe it, it shocked me that this man with all of his talent was a stockroom boy. But it was a delight to see him, and I saw him again several times of course.

What were the main lessons that you took away from your time with him that you still apply to what you do today?

AT: Well, the spirit of him and his unorthodox way of approaching the piano… he took liberties that other musicians didn’t take. He would often take an extra bar or an extra measure or even an extra two measures to make a statement. And he played so definitely, his rhythms were so definite. And he had a kind of rhumba bass and a junker right hand [after ‘Junker’s Blues’], that was so unique, unique to him. In fact it was so unique that even when we learned to play that style, if you heard him playing it you’d always know it was him. You would know that was the bop of the rock.

I’ve never been to a city where the piano player is treated as seriously in the field of popular music. I went to one bar where there were two pianos next to each other on stage and a bar man used to play percussion by beating his fingers with steel caps on them, onto a metal beer tray.

AT: Alright! Must have been Pat O’Brien’s…

That’s the one. It is hard to think of another city though where you had as many household name pianists working in popular music from one place at one time. Was there a lot of competition between you and, say, Huey Smith?

AT: It wasn’t competition. Everyone had their place and some followed others. Huey Smith was on the scene a bit before me and I followed Huey in some areas. The first time I played with Earl King, that was my first rite of passage from the teenage world to the adult world. And I substituted for Huey Smith who was ill one evening. I went to meet everyone at the Dew Drop Inn I had never been there before because it was for adults. So that night I played in Huey Smith’s place and a couple of years later, Smith was making a couple of hit records himself and he had to leave his band so they called me to take his place again. So it wasn’t competition, there was always a place for all of us.

You mentioned being a teenager… you were friends with Mac Rebennack from your teenage years weren’t you?

AT: Yes, definitely. Mac Rebennack and I were in the studio together as young teenagers. And when we were together I was always the pianist and he was always the guitarist. And a wonderful guitar player he was… and still is. He can arrange, write and do all the things. Whenever we were called into the studio at the same time Mac – Dr John – was always the guitarist but he turned out to be quite a pianist as well, as we all know.

It’s interesting hearing you talk about him beacuse I guess the impression that people in Europe often have of him is of this really wild, larger than life, very eccentric character where maybe the impression we get of you is of someone who is very collected and level headed maybe.

AT: [laughs] Well, I don’t know how to take that… I think of myself as a level headed guy but then that’s how I think of Dr John as well. I know he has a persona that seems really far out there but he’s a very cognisant individual.

I’m sure he is. I think I’ve just let my imagination run away with me while listening to Gris Gris…

AT: Well, sure… he’s very hip. He’s very cool. And he can be very eccentric… I do know that. But he’s wide awake and all of that.

It’s really interesting to talk to you because you’ve lived through so many different crucial phases in the development of so many different musical styles. For example, when you were around with Fats Domino, was there a sense in which it felt like there was something very special happening?

AT: Oh yes, yes. Fats Domino and Dave Bartholomew put us on the map for one thing. It felt royal being around Fats and Dave. It felt like they were in touch with the world when we were very local minded. Many of us were just having a good time [locally] and we had never thought beyond our own box. Dave and Fats were appealing to the world very early on, years before the rest of us got the message.

How did you come to work for [record labels] Minit and Instant at the end of the 1950s? And You worked on so many big records during this period.

AT: Well, Minit was just starting and there were two gentlemen, one who owned a record shop whose name was Joseph Banashak and the other gentleman was Larry McKinley who was a popular disc jockey. When they started Minit they were holding auditions at a radio station and out of most of the young musicians – the young kids around town – I was known as someone who knew all the songs of the day. So if they wanted someone to play behind them as they would audition, then I was their guy. So I was there to accompany several of these singers who were auditioning. So when the day of auditions was over the two gentlemen called me in. At that time they had thought that Harold Batiste was going to be their A&R man, however he was on the west coast with Sonny & Cher who were having their hey day at the time. But they asked me to fill the role until they could secure Harold and they knew I knew all the songs of the day. I immediately said yes, and right away they were very satisfied with me and I was elated to be with them. Harold Batiste stayed on the West Coast and I stayed with Minit and then Instant Records. And one of the auditions at that time was Jesse Hill’s ‘Ooh Poo Pah Doo’ and another was Ernie K. Doe, so things got started straight away and the rest is in the annals.

I went to the Mother In Law Lounge when I was in New Orleans… Ernie’s widow passed away a few years ago didn’t she?

AT: Yes, she did. She did on Mardi Gras eve.

What happened to her bar? I went into the Mother In Law Lounge and it had all of his stage costumes in there…

AT: Well, it closed for a very long time after she died but another musician in town by the name of Kermit Ruffin who is making quite a name for himself, recently he opened it. In the last month or so. So there is now a Mother In Law Lounge once more.

Did you find it frustrating when you were drafted in 1963? Because you’d really built up a head of steam by that point…

AT: Well, yes I did. I had been deferred and deferred… and yes, it did kind of stifle what I was about because I had been so free to record and so busy doing that. So yes it did put quite a hold on me for some time. But I was able to come home some weekends and do a little bit but I really wasn’t as into the swing of it as I would have been if I hadn’t been in the military. And many things changed about Minit and Instant when I was in the military. And when I came out of the military soon afterwards I dissolved my relationship with Minit as well. Not in a bad way, we’d just passed our season.

But after the military you entered into one of your most significant relationships with Marshall Sehorn. I was wondering what was the key to the success of that partnership?

AT: Well, Marshall Sehorn was a go-getter. He came out of that old school where you would sell records out of the trunk of a car if you had to. You’d visit radio stations up and down the road. He might take off to do some promotion and drive from city to city. He would go to record companies to set up deals with artist. And that was the kind of guy he was. So when he knew that I had dissolved my relationship with Minit, he wanted to work with me in any capacity. So I said, ‘Well, how about us being 50/50 in a company?’ And that’s how we got started. He was vital to me because he was such a go getter. He understood the business. And he was a real Southern guy, very likeable. He had Southern charm. It was a good relationship, I miss him dearly.

I don’t want to be too obsequious but you have written some of my all time favourite songs… And one of them would be ‘Hercules’ by Aaron Neville. When you were writing a track like ‘Hercules’ would you always know who was going to sing it?

AT: Yes. Whenever I wrote songs – particularly back then – it would always be for a particular artist. And Aaron is a very hip guy and very streetwise. If there was such a thing back then, then Aaron could have been the poster child for hip, street guys. Y’know, streetwise people. And the things that I said in ‘Hercules’, well, Aaron would understand that and would distribute that message with all the bravado it required and he did so very well.

Like a lot of people, I’m a fan of Lee Dorsey. From the little I know about him he strikes me as quite a forceful personality. Was it true he was quite a reluctant performer?

AT: Well, Lee Dorsey was a wonderful, high spirited, fun guy who always carried a smile. He carried a smile in his talk, on his face and in his heart. He had a wonderful time in his life. He was very good to work with. Very inspiring because he had such a happiness about him. He loved what he was doing when he was singing. He was a body and fender man when he wasn’t singing and even at his peak, when he would come off the road at the end of a successful tour, he would go and get into his grease clothes, his dirty work gear and go and work on cars. Straightening out fenders and painting bodywork. But really it was his finest hour when he was singing. He was a very good person for me to work with and he totally trusted me every step of the way.

And I’m guessing neither he nor you had been down a coal mine in real life?

AT: Never. We didn’t know anything about a coal mine.

You’re playing tomorrow night in Ronnie Scott’s in Soho. Now London is a very musical city. Prince had his residency in Camden recently, there are great heavy metal venues, great funk and soul venues etc. but all of these scenes are apart from one another. I get the sense that musicians are much closer together in New Orleans, that the genre boundaries are there to be crossed.

AT: Well, in New Orleans there are certain elements that ties us in. There are some ingredients we share. That second line brass band parade thing. The syncopation. The humour. And also the pace… our pace is a bit slower. But as for us covering the genres like that I think we’ve held onto the old world charm longer than most other places in America… maybe in the world but definitely in America. We take longer to get to the future than anywhere else in America. It took us longer to get from the upright bass to the electric bass guitar; it took us longer to get from the acoustic guitars to using amplifiers; it took us longer to get from a twin reverb to a Vox amp, which was as tall as a man sometimes. So we have held onto the old world charm more. As far as the genres go, we haven’t had to keep up with the speed that the other cities have, we didn’t have to keep up with being hip so we still have all the genres as part of our daily lives.

Another one of my favourite songs is ‘Break In The Road’ by Betty Harris…

AT: Good heavens! You mention that song…

I think it’s a perfect 7”. I wouldn’t change anything about it. Yet still the urgency of it, suggests that it was recorded in a very short space of time. Was it almost like a production line, they way that you worked around that period?

AT: Well, I was doing lots of things and trying to get everything done at once. I wasn’t mixing up a lot of concoctions if you see what I mean. There wasn’t a lot of time for bringing in an extra instrument to [dub over] the top. I was very, very busy and we worked hard. Lee Dorsey was very inspiring so I wrote a lot of songs for him very quickly. I was quite busy and there was quite a turn out of work if I look at it retrospectively. At the time we were just having a good time.

When you have a tune like ‘Break In The Road’, how long would it take from start to finish to get it recorded?

AT: Not long at all, something like ‘Break In The Road’ was very quick along with some other songs that day. Yes, we did a few songs that day. Always.

I’ve really enjoyed watching Treme. Along with the Spike Lee documentary, When The Levees Broke, it seems to tell a story that wasn’t getting told much in the mainstream media. What do you think of Treme and do you think it’s helping to redress the balance in the information that’s getting out there about life in New Orleans post Katrina?

AT: Treme has been wonderful for New Orleans, just wonderful. It has drawn attention to New Orleans that it wouldn’t have gotten otherwise. Also it’s a snapshot of the whole situation, because how much can you get into a TV series even, given how much history New Orleans has. But they rolled out the red carpet and they did a wonderful job on the genres that they covered and the way that they covered it. I thought it was a first class job and I feel very good about the show. It made people who hadn’t previously given it a thought think, ‘I must get there.’ And of course, we love that.