Portrait courtesy of Edd Westmacott

People often say the Chatham Dockyards are docks; they’re not – it’s a dockyards. Originally they built warships there, going all the way back to the Elizabethan period, and the Dutch actually attacked the British fleet in Chatham in 1667. Volunteers from the yard were asked to help fight the Dutch, who were burning ships at anchor because they’d been laid-up. I think the idea was that the Dutch would drop back on the tide, then go up the Thames and take London, so they started evacuating London as well. But the Dutch decided they couldn’t be bothered and went home instead, taking the British flagship [HMS Royal Charles] with them. The stern is still in Amsterdam. Before they got to Chatham, they took Sheerness and landed in Lower Gillingham. The locals said the Dutch sailors were much more polite than the British ones.

HMS Victory was built in Chatham and offered back to the dockyard about 70 or 80 years ago. We’d be very pleased to have it, but it was restored in Portsmouth, where it remains. The Temeraire was built here, too, and my band The Spartan Dreggs did a little song about it, ‘The Fighting Temeraire’.

The yard closed in 1984 primarily because no real ship-building was going on

When I was working at the dockyards as an apprentice stonemason in 1976, they were mainly doing re-fits – of warships and also nuclear subs. No real building. Then, after there was a huge reduction in the naval fleet, there wasn’t any need for people to be doing up ships.

The closing of the dockyard devastated the area’s economy

It’s 30 years now since the dockyard was closed by Margaret Thatcher. After it closed, north Kent had the same unemployment rate as mining towns in the north of England, although we’re in the heart of the southeast. Everything fell away, because the dockyard was the main employer and many of the other industries around here supplied the dockyard. It’s a massive, walled dockyard with three huge basins and the whole thing was one big community that ran itself. My grandfather on my mother’s side worked there as a storeman, and his father was a shipwright. They’re the skilled side of the family. My father’s grandfather was Royal Navy. They were farmers, but he ran away to sea in 1913 as a ship’s boy and fought during the First World War as an AB [Able Seaman]. Then, after he retired from the Navy in the 1930s, I think he went and worked in the yard as well. My mother’s mother’s side – the Lovedays – they were all Royal Navy as well. There were about 13 of them.

The dockyard, and Short Brothers, connected all the towns around Chatham

Around here, you’ve got Gillingham, which is a bit separate, then you run down the A2 and you’re in Chatham. The high streets in Chatham and Rochester are now connected, then you go under the bridge and you’re in Strood. In the area, you also have Brompton, where members of my family also lived, but it feels like one big mass bunched round the dockyard, and also [aerospace company] Shorts, where they built flying boats and the Short Sutherland plane. Shorts moved to Belfast in the late-eighties, but if you ask almost anyone round here – if they’re from here – where their parents worked, they’ll say the dockyard or Shorts.

Working on the dockyard certainly wasn’t a job for life

I was told when I was working at the dockyard that I was stupid to walk out, because it was a job for life. But that was one of the things that encouraged me to walk out, and then it closed. I did the right thing and I had no sentimentality about the yard closing at all. It was boring, because you had to go to work, and when you worked at the dockyard, you were being made to be somewhere you didn’t want to be for a long part of your life, like with most jobs. I felt nothing when it closed, other than being self-satisfied that I was right about it not being a job for life. That wasn’t me being callous, that was me being smug.

The closing of the dockyard heightened my dislike of Margaret Thatcher

As far as other things going on, I was very anti-Thatcher and if I had been asked about it then, I would definitely had said closing the dockyard was the wrong thing to do. We had mines in Kent as well and I was supportive of them because, in general, I think people deserve and require meaningful engagement in their lives and most of us can’t manufacture that. In that sense, closing the dockyard and the mines was the worst possible thing that could have happened to the area – it caused massive economic decline. It’s the same thing that the whole country suffered under Thatcher, but it was heightened here and probably only comparable to mining communities in the north. It changed the character of the towns here; they became less violent and more scummy. When I was a kid you could get punched easier, but it was less yobby. No one at my secondary school took drugs. People like my brother, who went to a grammar school, might have – the pretend hippies, or wallies, as we used to call them. Now all kids take drugs. I think it might be a bit harsh to blame Thatcher for that, but I’m prepared to do it.

Being a dockyard stonemason is not a job for an artist

St Mary’s Island is near the dockyard and that’s where they used to dump the nuclear crap. They’ve now built an expensive, exclusive village there, but people aren’t allowed to grow vegetables. Lumps of old stone were dumped there, too, and I used to go out and do carvings in my lunch hour because it felt a bit like doing art. I’d left school at 16 with no qualifications and wasn’t allowed to go to art school. But then I started getting sent to London – to building college in Stockwell, where you had to know geometry and maths, which I don’t know at all. I was being taught how to carve perfect blocks and cubes, and doing identical little mouldings. That was not my idea of fun.

In its own way, being an apprentice stonemason led me to discover me to punk rock

I used to stay up in London with my brother, who was studying art at Slade, and that’s how I got to hear punk rock. He lived in a squat in Chalk Farm and I heard the Sex Pistols on the jukebox at the London University student union. I was 16.

Journalism headlines are as bad now as they were in 1976

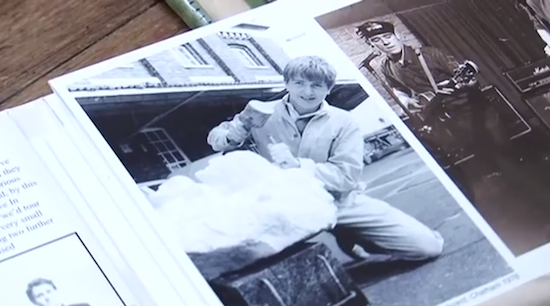

It’s a bit unusual that there’s a photo of me as a stonemason. There was a NATO exercise in the North Sea where a minesweeper got dragged underwater and several fellas were killed. They brought in one of the nuclears from the exercise with the coffins on the back; the admiral was there, they did the ‘Last Post’ and we all stopped work. The photographers all walked back from this event and took a picture of me doing my carvings in my dinner hour. It went in the newspaper with a headline like, ‘Chips With Everything’, then something along the lines of me not being able to stop working at his new job and making my carvings in my dinner hour. And here you’re calling this section ‘Billy Holiday’. Clearly, journalism hasn’t increased in wit at all in the last 35 years.

The council have no regard for the towns around the dockyards

The great thing about the Historic Dockyard is that we’ve got one and they’re preserving the older part of the yard. It adds a huge amount to the area having that; it’s a tourist destination and a film set. It isn’t the best result for the dockyard, but it’s the obvious result. I’ve got a big old, draughty studio there, so I’m back in the yard again and have been for the last four years. It’s a fantastic space; unfortunately, though, it’s outside the town – between Gillingham and Brompton, ten minutes brisk walk from Chatham town centre – and all of these places were devastated by the end of the dockyard. The council had already started kicking the hell out of the town centres before the yard was closed, and now it’s getting worse. Medway is a very strange place; it’s 40 minutes from London and even Rochester, which has one of the best Norman castles and a fantastic cathedral, doesn’t have any serious gentrification. But now a Costa is opening where the flower shop is, or was; a McDonald’s is coming; and a Subway has opened where there used to be a little independent greengrocer. What we really need, and I’m sorry I [have] to say this, is some ponces from East London, who have got mates who are lawyers, to come down here, buy nice cheap houses [and] set up some decent places to eat and have enough power to stop this council from destroying the infrastructure. We need a few ponces; I can’t do it all by myself!

Preserving the dockyard gives it meaning

Unfortunately for the dockyard, they’re in somewhere of a nowhere zone, but, apart from that, it’s good for tourism and it should be preserved. It’s very easy to get picky about these things. My son Huddie, who’s 14, came and did some painting with me yesterday. He’s got a very gentle aspect – he’s not as jagged as me – and he wasn’t over-plussed with his picture. I said to him, ‘You’ve got a picture there that wouldn’t exist if you hadn’t done it, and that’s its meaning; that’s why it’s worth doing.’ You could say how you think the dockyard should be, but debating how it should be is better than not having it, and that goes for a huge amount of stuff in the world. I think it’s very important to have a sense of history. There’s a balance, though – we needn’t be jingoistic; we just need to show an aspiration towards learning and intelligence.