Much if not most of the music we consume in the West during these early years of the 21st century is of secular origin. The religious, sacred or spiritual motive for composition, which arguably inspired most rhythmic, melodic or sung composition from the moment that early humans started clattering sticks together to ward off evil spirits at night, has gradually faded from the pop consciousness, for reasons that would take longer than we have here to fully explore. This is, I feel, something of a shame, for as our list of tracks below proves, the sacred, spiritual, mystical and religious has given us some of the most beautiful and profound music ever composed or recorded.

I was especially struck by this on a recent Sunday afternoon, during a walk through a London market – wandering past stalls with transistor radios tinnily blaring national pop radio, I stopped for a while to look at something or other, only to find music bleeding into my ear’s periphery from two very different sources. From an open window above, the raised, ecstatic voices of an African Evangelical congregation. From a shop doorway, a cassette of Islamic chants, with each Arabic line followed by its translation into English in a calm, thoughtful voice. Our Western secular contribution to the ambient noise felt rather tawdry by comparison.

You shouldn’t have to be a believer to appreciate religious, spiritual or mystical music, to admire and respect the motivation for its creation, even to be moved by it. Our very own metal Vicar, the Rev Rachel Mann, put this very succinctly in this week’s Quietus Essay.

In this list we’ve tried to be as broad as possible in our reach, a multi-faith gathering from all corners of both music and belief, with the Quietus writers selecting everything from pagan folk to Sufi quawwali to Christian gospel, chant and techno, Rastafarian roots reggae to Buddhist funeral chant and electronic composition, Jewish psalms to New Age. It is, by its very nature, a subjective list and far from comprehensive – please do let us know what you’d have selected in the comments section below. Luke Turner

Words: Jude Rogers, Noel Gardner, Lisa Jenkins, Rory Gibb, John Doran, Luke Turner, Laurie Tuffrey, David Bennun, Mark Pilkington, Matt Evans, Sean Kitching, Sophia Deboick, Barnaby Smith, Charlie Frame, Wyndham Wallace, Tristan Bath, John Freeman, Jamie Skey, Ian Wade, David Bell, Nick Hutchings, Daniel Quinn, Stewart Smith, Lee Arizuno, Rev. Rachel Mann, Gary Suarez, Joseph Burnett, Kate Hennessy, Matthew Kent, Toby Cook.

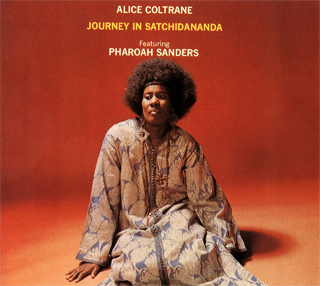

Alice Coltrane – Journey In Satchidananda

On a first listen, you might feel like you’ve stepped off the edge of the world and found a new home. Cecil McBee’s bass lullaby maps a benign darkness; Tulsi’s insidious tambura loop dissolves your sense of self; Alice’s golden harp flutters; Pharoah Sanders’ soprano issues softened solar flares. It’s like sinking into infinity, original bliss. Time feels cyclical rather than linear.

Satchidananda was a yogi who set up an ashram on the US West Coast and delivered a keynote speech at Woodstock (Jeff Goldblum was another devotee, hence that "I forgot my mantra" cameo in Annie Hall). But there’s no hint of period-piece sanctimony or naivety in this journey; this is the experience itself, the light, space and motion that searchers wanted a taste of. "Knowledge, existence, bliss," as Coltrane translated his name. Lee Arizuno

The Joubert Singers – ‘Stand On The Word’

I have Chris Lowe to thank for this. In 2005, the Pet Shop Boys curated a double CD for the Back To Mine series. Neil Tennant’s was a woozy trip through Edward Elgar, Etienne Daho and Harold Budd. It was music for the party comedown, gentle, classical and meditative. Chris Lowe’s was not. Here was the high-octane, Italian pop-opera of Matia Bazar. The sun-struck early 80s electro of The Flirts and Mr Flagio. Carl Bean’s 70s gay anthem on Motown, ‘I Was Born This Way’. And then came a bright, sad piano, its funky bassline descending step by step, every ring of an ivory key raising a hair on the neck. A simple drumbeat followed, like a handclap, then a sustained, wordless note sung by high voices, before those divide into louder, more sinewy harmony.

And then come the men: "That’s how he works. That’s how. The good lord. He works."

‘Stand On The Word”s history is hotly debated, so at the risk of the wrath of crate-diggers, here’s the best version I can find. Written by gospel choirleader Phyllis Joubert, this song was originally recorded in 1982, in the First Baptist Church in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. It is the opening track of a privately-pressed LP called Somebody Prayed For This, and credited on the inner label to the Celestial Choir. Initially copies were made exclusively for the church congregation, but one fell into the hands of DJ Walter Gibbons, the pioneering innovator of beat-matching, editor of the first commercial 12" single (Double Exposure’s ‘Ten Percent’ from 1979), and a man in the process of becoming a born-again Christian. Gibbons’ style and taste hugely influenced Frankie Knuckles as well as Larry Levan, who added this song to his sets at the Paradise Garage. A later version was recorded by the Joubert Singers, and Larry Levan’s name slapped onto the bootleg.

Ever since, ‘Stand On The Word’ has gained mythical status, and its current listing on Discogs shows its worth in dollar signs. As someone who found it years later, I find its worth in other ways. I find it in the way so many sensations of unbridled joy are dizzily, but skilfully, built up. I find it in the way its funky piano figure ripples like sunlight, while keeping a sense of deep yearning shimmering at its edges. I find it in the sweet, off-key delivery of the soloist singing "we don’t know how, we don’t know where", and in those handclaps with which you can’t resist joining in. I also find it in the sheer power of a chorus of amateur voices, who convey a real, profound sense of togetherness. Someone called Boxedjoy over on ixlor.com nails its impact perfectly: "Can’t we just credit this to God?" Jude Rogers

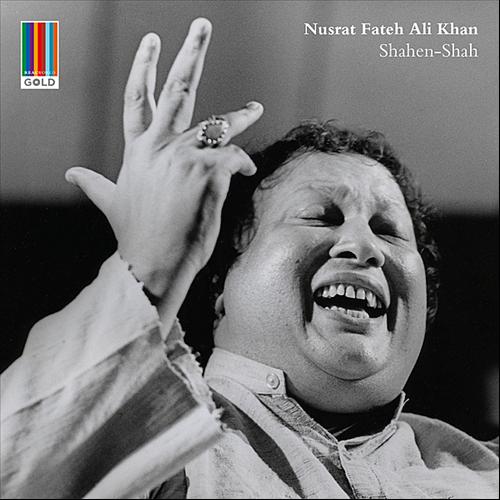

Nusrat Fateh Ali Kahn – Shahen Shah

The wonderful cover for this, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s second album, perfectly encapsulates the man as both singer and vehicle for intense, devotional emotions. Khan raises his right hand skywards, his eyes clenched shut as if enraptured, the intensity of the moment somehow amplified by the black and white grain of the photo. Famed as one of the great masters of the Sufi devotional music qawwali, while listening you get the sense that this is a man who rejoices in his music. Indeed, Shahen Shah has a joyful, exuberant energy running through it, as Khan’s backing vocalists and musicians come together to join in his open-ended prayers-turned-into-songs. Shahen Shah is an epic album in scale, running over an hour in length over six tracks, giving lucky listeners the chance to bask in one of the most deeply affecting, masterful voices ever committed to record. Khan’s delivery is precise, emotive and captivating, and rarely has it had such a fine vehicle to be shared with the world than it does here. Joseph Burnett

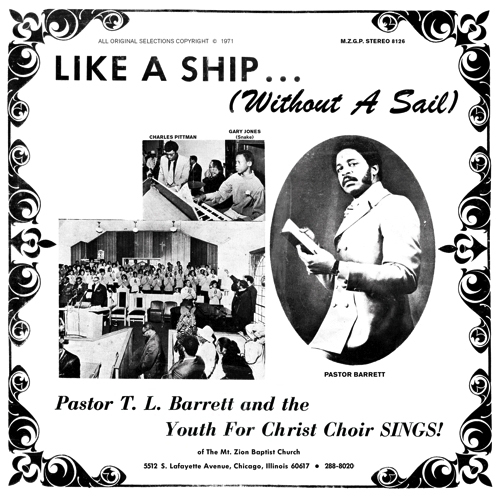

Pastor T.L. Barrett & The Youth For Christ Choir – Like A Ship… (Without A Sail)

When the founder of the Northern Californian State Youth Choir, Edwin Hawkins, recorded the 18th century hymn ‘Oh Happy Day, That Fixed My Choice’ (as a funkier ‘Oh Happy Day’) in the Ephesian Church Of God In Christ, at Berkley, Ca, in 1969, he inadvertently helped revive the fortunes of gospel music. In 1971, an observant Pastor T.L. Barrett knew what he needed to do in order to attract young people back to his under-attended Mount Zion Baptist Church, Chicago – and self-released Like A Ship Without A Sail. In the intervening four decades, this private pressing has achieved a well deserved reputation among collectors for its deep grooves (courtesy in part to the album’s sax player and arranger Gene Barge and guitarist Phil Upchurch both moonlighting from day jobs at Chess) and belting vocals by the righteous Pastor and his choir. Luckily for the rest of us, those lovely people at Light In The Attic have reissued the album in all its glory. Hallelujah brothers and sisters, hallelujah! John Doran

Arvo Pärt – ‘Magnificat ’ (Choir Of Kings College, Cambridge)

I was initially going to write about Arvo Pärt’s Cantus In Memoriam Benjamin Britten, but though it encapsulates a sense that in the composition of music and the creation of art, humans are able to attain a sense of immortality, I’m not sure it’s quite specifically devotional enough to warrant featuring here. Instead, I’ve chosen one of Pärt’s arrangements of Christian music that has resounded down the centuries. ‘Magnificat’ is often sung as part of the Vespers, the evening service shared by many Christian traditions, and referred to in the Church Of England as Evensong. It’s a quiet, reflective, thoughtful service that I think could be appreciated aesthetically by non believers and believers alike, especially when encountered in the darkened confines of one of our ancient religious buildings at dusk – those medieval architects knew what they were doing.

Composers including Bach have set the ‘Magnificat’ in rather exuberant style for the full orchestra; Stanford’s rendering, meanwhile, I find rather trill and fussy. Pärt’s 1989 interpretation of the Latin text, however, is for choral voices alone, and as such has a wonderful grace and power. He makes wonderful use of dynamics and drones, as well as an a method, developed by Pärt and based on his study of early music, which he calls tintinnabuli and explains thus: "Tintinnabulation is an area I sometimes wander into when I am searching for answers – in my life, my music, my work. In my dark hours, I have the certain feeling that everything outside this one thing has no meaning." As well as a musical technique, this to me rather beautifully sums up the moments of transcendence that can come with belief. Luke Turner

Lust Control – ‘The Big M’

Why, you might reasonably ask, have I chosen a semi-ironic punk song from the wasteland of late 1980s Christian rock? Well, partly because I am a hapless manchild left puzzled and embarrassed by sincere expressions of emotion. But also because the song is inexplicably great, and allows me to give a minute shoutout to the one form of spiritual music which almost no-one ‘on the outside’ takes seriously: contemporary Christian music, or CCM. Founded in Texas by Christian rock magazine editor Doug Van Pelt, Lust Control played basic, thrashy punk before the genre had developed a faith-rooted scene. Pretty much all their songs are rubbish, which I found out by buying a Lust Control CD after hearing ‘The Big M’ on a compilation of so-called outsider music. Aptly for a song which decries masturbation as a sinful act of non-procreative lust, I suggest you keep yourself pure and listen solely to the above YouTube link.

In its eagerness to adopt the tropes of punk, ‘The Big M’ gets them blessedly wrong, a recipe for many amateur classics of the genre. The backbeat is so rigid, I initially thought it was recorded with a drum machine. The guitarist alternates between rudimentary powerchords and teenager-in-bedroom wanking, an irony not lost on Van Pelt who yells "STOP! DO A GUITAR SOLO INSTEAD!" That Lust Control employed a degree of knowing humour does not preclude the sincerity of their message. "THE BODY IS NOT MEANT FOR SEXUAL IMMORALITY, BUT FOR THE LORD!" the singer proclaims, as serious as Crass urging us to "fight war, not wars" or Ian Mackaye explaining his avoidance of narcotics. Not that Lust Control bear too much comparison to anarcho or straight edge, didactic as these subsets of punk can sometimes be. ‘The Big M’ is more akin to the singular flashes of inspiration heard on the Killed By Death and Messthetics compilations; if it had been recorded a few years earlier, and emerged from a different subculture, it would surely feature on one. Noel Gardner

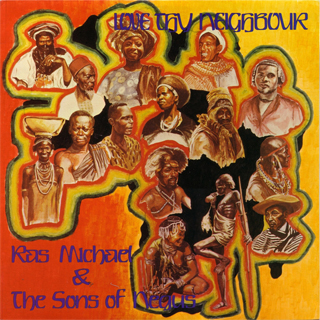

Ras Michael & The Sons of Negus – Love Thy Neighbour

As one of the branches of traditional Rastafarianism, Nyabinghi is deeply ingrained in Jamaican religious culture, and the hymns and chants from that particular sect have continually influenced more popular strains of reggae and rocksteady. Ras Michael might be considered one of the more classical proponents of the music, often performing using the traditional hand-drumming techniques and chants as a continuing of the religious recitations with his group the Sons Of Negus (this amazing warped VHS recording of the group performing for L.A. Reggae, and including an interview with Michael, is a must-watch). In their recorded work he consolidates these traditional methods with more popular aspects of reggae, and on Love Thy Neighbour in particular the results are spectacular, combining percussive complexity and dub essences (no doubt from the influence of mixing engineer Lee Perry) into a mesmerising work. Matthew Kent

Abhidhamma 7 Verse Incantation, Thai Buddhist Funeral Chant

I grew up with the West’s view of death: that it was one of the worst things that could happen to anyone. It was the end, finite and there was no other way to rid yourself of the pain of loss. My mother died when I was nine, and although she was agnostic, we put her to rest in a Christian church with all the tears and solemn ceremony that surrounded it. For me, even as a young child, something about the rituals of death brought me no comfort. Years later my family found themselves living in South East Asia, and in Thailand for number of years. My father, then in his fifties, converted to Buddhism – although it was less like a conversion and more an understanding of a different set of life’s lessons. It was peaceful, non-judgmental, guilt free and inclusive. After spending quite a bit of time in Thailand myself, I began to try to see life and death from a different perspective.

This piece of music is the perfect antidote to the visceral pain of death. Beautiful in its simplicity. Sombre but uplifting at the same time. This is a teaching of impermanence, suffering, that which is, and that which is not. It is intended to alleviate the suffering of those relatives and friends who are still alive, and in the knowledge that the suffering of those that have left us has indeed ended. It has always bought me peace at moments of sadness and, as much as anything, it is just a beautiful piece of vocal music to soothe the soul. Lisa Jenkins

Steve Reich – Tehillim

Following his groundbreaking music in the 1960s and 70s, from tape-phase pieces through to full ensemble works, Steve Reich’s 1981 piece Tehillim is at once a continuation and a shift from his previous work. It’s still immediately recognisable as his own, with those distinct, tightly interlocked pulses, and a chorus of female lead voices that weave gradually in and out of phase with each other. But it’s the first of his work to explicitly explore his own Jewish religious heritage, which Reich had become increasingly engaged with through the second half of the 1970s – his parents were Jews of European descent, something he alluded to again later, in 1988’s immensely powerful Holocaust reflection Different Trains.

For Tehillim he chose to set four Hebrew Psalms to music, a decision in part informed by the fact that by the fact that the traditional melodies for singing the Psalms had been lost in European Jewish traditions. "This meant I was free to compose the melodies for Tehillim without a living oral tradition to either imitate or ignore," he explained. So, while still drawing from the pulsing, minimalist approach to melody and rhythm he’d helped pioneer during the previous decade, he scored the piece in continuously changing metre, to follow the patterns of the human voice reciting the Psalms: "The heavens declare the glory of God / And the works of the firmament show His handiwork." The result is music of glorious fluidity that feels at once traditional – tied into a centuries-old religious history – and distinctly modern in style. There’s a gorgeous moment not long into the first movement where handclaps and drums drop out, and the voices soar, the phase effect multiplying four singers into an audio illusion of choir many people strong. Together they arc and wheel in joyful collective motion, like a flock of starlings over the sea at dusk. Rory Gibb

Gloworm – ‘Carry Me Home (Will’s Proscrastinatin’ Mix)’

This, right here, is why gospel, out of all forms of devotional music, is the one that appeals most to secular types like myself. Because it’s not, appearances to the contrary, about God. Or at least, not principally about God. It’s about the longings of the human heart. It speaks right to us. We all want to be consoled. We all want to be healed. We all want to be loved. We all want to be saved. And the absence of faith doesn’t alter that one whit.

Dance music went big on gospel in the 90s. Not surprising, given the parallels between religious ecstasy and… you know, being on the irreligious sort. This was one of its very finest expressions. A storming hard house tune by British producer Will Mount, and a magnificent vocal turn from one Sedric Johnson, of whom I know nothing else other than that he previously led the Long Beach Choir. When Johnson testifies, he links the sacred not with the profane, but the mundane, invoking "the life that everybody goes through" – at least, I think that’s what he sings – in details both quotidian and profoundly moving. Whether I’ve heard the words quite right never mattered. Because they’re the gospel truth, either way. "And Lord, oh Lord, I did everything I could do." Don’t we all. Preach, brother. David Bennun

Foster Manganyi – Ndzi Teke Riendzo

Like some of the best recordings on this highly subjective list, Ndzi Teke Riendzo was recorded with the practical aim of boosting congregation numbers in a specific church or denomination. Foster Manganyi is a pastor from Giyani, Limpopo who made this infectious album (originally dubbed onto cassette for his flock) in 2007. Those hearing a resemblance to the Shangaan electro sound aren’t imagining things – Nozinja produces both, and both styles of music share that hectic electronic marimba and whistle stomp, with catchy South African melodies. However, the elderly parishoners of Pastor Manganyi’s church must be relieved that his songs come in at a slightly more relaxed pace than Nozinja’s usual 190bpm fare. John Doran

Anchiskhati Choir – Polyphonic Voices Of Georgia

The pre-Christian choral music of Georgia is considered to be one of the earliest examples of polyphonic singing in Europe. Georgia’s location in the Caucasus, on the border of Europe and Asia, makes it a country rich in traditional music, with UNESCO even going so far as to give Georgian polyphonic singing the ungainly accolade of ‘Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity’. If that sounds excessive, take a listen to these recordings released through Soul Jazz’s World Audio Foundation sub-label. Researched and recorded by a passionate group of singers and ethnomusicologists, following the near-loss of the tradition at the hands of the Soviet Union, there is something genuinely moving about the ancient, complex harmonies contained herein; a music that epitomises the word ‘sacred’. Charlie Frame

James Brown – ‘The Old Landmark’

If ever a song is able to make you see the light, it’s this one. It certainly worked for Jake & Elwood in the Triple Rock Church, during an unforgettable scene from 1980 movie classic Blues Brothers. So well, in fact, that John Belushi as ‘Joliet’ Jake ends up flipping towards the altar – or at least his padded body double does. After all, when the inspirational preacher at the pulpit is Reverend Cleophus James, better known as James Brown, it would be a sin not to dance. Brown’s star was on the wane at the time, but his inclusion by director John Landis, in addition to Cab Calloway, Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin in speaking roles, caused costs to spiral and tempers to fray with the Universal Studios. Apparently, as Elwood is metaphorically "turnin’, yearnin’, learnin’, burnin’", at the front if you look down towards the knave you’ll catch a glimpse of a technician scurrying to get out of shot. But, truth be told, you won’t notice anything other than a resurgent Brown given a new lease of life.

Brown was born to do this. He was raised in the church and sang in church choirs for two-and-a-half years, later touring with the Reverend Willingham’s Sewanee Quintet and recording an album with James Cleveland’s South Californian Community Choir. It is the latter who back him up in the movie, alongside a youthful Chaka Khan, front and centre. Also known as ‘Let Us Go Back To The Old Landmark’ this song was originally written by W. Herbert Brewster in 1949, and has also been recorded by The Staple Sisters and Dionne Warwick, but Brown’s version is the hardest to ignore. Nick Hutchings

Mahavishnu Orchestra – The Inner Mounting Flame

Like The Beatles before him, Yorkshire born guitar maverick John McLaughlin sought creative and spiritual inspiration in the East, in his case through Indian guru Sri Chimnoy. But even before his first meeting with the sage, McLaughlin had begun immersing himself in Eastern mysticism around 1962, via London’s Theosophical Society, where, he later told King Crimson guitarist Robert Fripp in a 1992 interview, "I felt I was walking into a new world… everything was possible… everything’s magical, nothing’s ordinary". After McLaughlin, aged 27, finally met Chimnoy and asked him "what’s the relationship between music and spirituality?" the sage gave an answer that led the guitarist to become a devout disciple. Chimnoy replied: "Well, it’s not really a question of what you do. It’s what you are or how you are that’s important, because you can be making the most beautiful music sweeping the road, if you’re doing it in a harmonious way, in a beautiful way".

McLaughlin’s relationship with Chimnoy became equal parts blessing and curse. At first, it provided the driving force behind the guitarist’s vision, giving rise to the band’s name (which means "divine compassion, power and justice") and fiery, intense, Eastern-inflected sound, which was supreme in their 1971 debut The Inner Mounting Flame, an often-imitated-never-bettered, landmark fusion record. On the flipside, however, McLaughlin’s ties with Chimnoy incited outright "animosity" among the other band members, who rejected their spiritual ideas. The original line-up split in 1973, leaving in their wake a modest legacy, but The Inner Mounting Flame will always remain their fiercest, most enduring statement. Jamie Skey

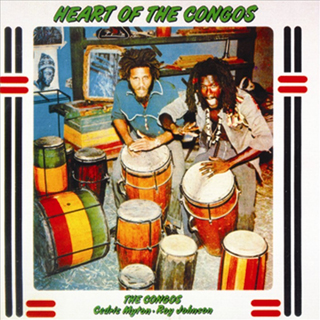

The Congos – Heart Of The Congos

Few records bristle with Old Testament fire quite like Heart Of The Congos. Thanks in no small part to the roots reggae scene, and particularly the rise to prominence of its poster boy Bob Marley, the Rastafari movement had by 1977 grown into a globally recognised belief system. Spiritual lyrics had been a common fixture throughout Jamaican music since the late 1960s, but while much of roots music concentrated on the social struggles of the urban tenement dweller, the Congos evoke a return to the rural beginnings of the Rastafari movement. Heart Of The Congos follows common themes of Bible stories (‘Ark Of The Covenant’, ‘Sodom & Gomorrah’), repatriation (‘Open Up The Gate’) and praises unto Jah (‘Solid Foundation’). However the songs themselves are elevated to new heights by Cedric Myton’s ringing falsetto and Roydel Johnson’s sage-like harmonies, making for some of the most heavenly voices heard in any genre. Add to this the dusty, ancient-sounding quality of Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry’s highly innovative production techniques: on ‘Congoman’, Perry manipulates traditional Nyabinghi drumming to create an almost techno-like rhythm on which to carry the Congos’ eerie chants. Meanwhile, the animal call of a toy moo-box fed through an echo chamber on ‘Children Crying’ has the peculiar effect of transporting us to the Jamaican hillside communities from where Rastafari originated, and across the ocean back to the movement’s African heartland. Charlie Frame

Coil – ‘How To Destroy Angels (II)’

"We’re trying to release something within the listener… we’re trying to put people in touch with something of their subconscious" John Balance, 1985.

Over their twenty-plus year career Coil always had one eye in the gutter, another fixed on the stars, and the third turned inwards to the heart of it all. As individuals, and as musicians, John Balance and Peter ‘Sleazy’ Christopherson set out on a Herzogian journey in search of… something. The quest cost the duo blood, sweat and tears in heroic quantities – and perhaps their lives – as they ingested uppers, downers and inside-outers, joined occult orders, absorbed recondite texts, pushed their bodies to the limits and, aided by a shifting pack of like-minded collaborators, produced some of the most beautiful, strange and haunting music of their time.

Any number of tracks, or whole albums (Time Machines and Astral Disaster at the top of the pile) qualify for inclusion here, but I decided to go right to the source with this smoky remix, by Stephen Stapleton, of Coil’s first release, ‘How To Destroy Angels’, from 1984. Dedicated to Mars, ‘How To Destroy Angels’ is a seventeen-minute ritual drone for gongs and bullroarers whose sparse, ancient instrumentation calls out across time. Intended "for the accumulation of male sexual energy", it’s an extension and refinement of their earlier neo-primitive experiments on Psychic TV’s Themes EP.

Where the original How To Destroy Angels recording is stripped down to its assets, Stapleton’s slow-pan, deep-phase overhaul sounds convincingly like being present at the original session while munching a lightly-dosed Mars bar. The atmosphere ripples, slides and shimmers with each gong wash; mosquitos whine and air elementals groan and gurgle about your ears, creating a potent, charged environment for the contemplation of form and emptiness, stillness and motion, life and afterlife. Mark Pilkington

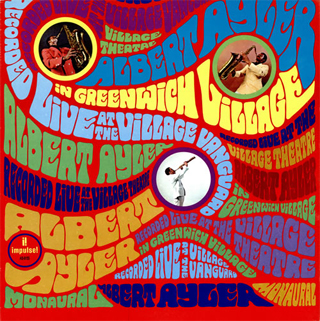

Albert and Donald Ayler – ‘Our Prayer’

"Trane was the father, Pharaoh [Sanders] was the son, I am the holy ghost", said Albert Ayler of his place in the trinity of spiritually-minded 1960s jazz saxophonists. Like that of his friend and mentor John Coltrane, Ayler’s music was profoundly spiritual. Music, as the title of his 1969 album proclaimed, was the healing force of the universe, a universal language which brings the truth marching in. "That truth is that there must be peace and joy on earth," he told Downbeat‘s Nat Hentoff in 1966. Raised in the Baptist church, Ayler brought an ecstatic gospel fervour to avant-garde jazz. As he explained to Hentoff, "It’s really free, spiritual music, not just free music… we are trying to rejuvenate that old New Orleans feeling that music can be played collectively and with free form. Each person finds his own form." To break free from the head-solo structures of bop, Ayler looked to the polyphony of New Orleans jazz, where players would improvise simultaneously around a lead melody. Ayler would often base performances around simple melodies reminiscent of folk songs, hymns or military marches, before exploding their harmonic and rhythmic structures in a rapturous free improvisation. How to listen to such music? "It’s a matter of following the sound… I mean, you have to try and listen to everything together," said Ayler.

The music Ayler was making in 1966 is arguably his most spiritually uplifting. Special mention must go to his brother Donald, who contributed one of the most beautiful melodies in jazz history, ‘Our Prayer’, to the repertoire. Donald, who died in 2007, is an unjustly overlooked figure, overshadowed by his charismatic brother. Some critics dismissed Donald’s trumpet playing as amateurish – he was an alto saxophone player who only took up the trumpet to join his brother’s band – but as John Litweiller notes, Donald’s sound recalls the best early lead trumpeters, with an expressive vibrato on sustained notes, and a piercing golden tone that cuts through the stormiest improvisations. The influence of New Orleans polyphony on ‘Our Prayer’ is clear. Donald Ayler takes the lead role, stating the main eight bar theme, around which Albert and violinist Michel Samson, as the other frontline players, improvise variations and counterpoints. Furthermore, the melody has a hymnal quality and the stately rhythm of a New Orleans funeral march; compare it to George Lewis & Euraka Jazz Band’s ‘Nearer My God To Thee’ from the 1920s. The brothers would go on to perform ‘Our Prayer’ at John Coltrane’s funeral in 1967.

In the interview with Hentoff, Donald noted, "The thing about New Orleans jazz is the feeling it communicated that something was about to happen, and it was going to be good." ‘Our Prayer’, for all its elegiac qualities, conveys that sense of hope. In the Live at Greenwich Village recording from December 1966, the longest complete version at over four minutes, shimmering violin and bowed bass swell up around Donald’s dignified statement of the theme, while Albert provides harmonic counterpoint, before pulling away from the centre with heavenly glissandi and rubato variations on his brother’s eight-note fanfare in the sixth bar. The theme and variation structure continues for a minute or two, before a raw outburst from Albert takes the band completely out, with drummer Beaver Harris pounding out an open pulse beneath flailing cymbals and Samson peeling the paint from the walls. The brothers make like Holy Rollers, speaking in tongues and offering their music up to God, before returning to the theme. This time Donald remains constant while the other players move around him more freely, slipping in and out of the harmonic structure, before resolving on a gorgeous gospel cadence. Stewart Smith

Georgia Sea Island Singers – Join The Band

Em-eye-double-ess-eye-double-ess-eye-double-pee-eye! Mississippi – a tiny US based DIY label – have recently reissued some crucial 20th century recordings… and this collaboration with the Alan Lomax Archive can arguably be called the prime among them. On two different trips to St. Simons Island, Georgia, in October 1959 and April 1960, Lomax captured one of the definitive American folk artefacts. Very rarely is the live element of an album so immersive, with every handclap, every cough, every foot stomp, every exhortation, every creak of a wooden floorboard, dropping you into an amazing world that’s already all but gone. Bessie Smith is the star of this disc and her version of ‘Oh Death’ has to be heard to be believed; of course, it doesn’t feel so much as a shadow falling over your grave as it does weight being lifted from your shoulders. And yeah, it’s got that Moby tune on it, if that’s your thing. John Doran

Gamelan Munggang

Munggang is the most ancient gamelan ensemble of Central Java in Indonesia, and its melodies consist of just three tones. Because of the limited melodic scope of the instruments, Munggang is its very own mini-genre today, although it would have been the predominant gong music in Java when it first originated many centuries ago. The first set of instruments is said to have been constructed in the 4th century AD and used to accompany important social and spiritual rituals. Islam did not become the predominant religion in Java until well over a thousand years after this. The simple, repetitive, circling motifs played on the Munggang instruments are associated with the mix of local indigenous animistic beliefs and Hinduism prevalent in the era of the Majapahit empire.

The music is known also as Gending Lokananta – which means ‘supernaturally produced gamelan music from heaven’ in Javanese. That this music is particularly archaic has led it to become especially revered by both players and audiences. Passed down over millenia, these are not melodies to be played or listened to casually. It remains a mystery where the very first gong instruments in Java came from originally, although there are similar ensembles to be heard even today as far away as Mandalay in Myanmar. Daniel Quinn

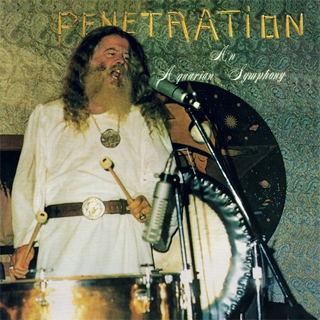

Ya Ho Wha 13 – Penetration: An Aquarian Symphony

Originally released in 1974 in a small run of around 500 copies on the Source Family’s own Higher Key Records imprint, and sold out of the back of their whole food vegetarian restaurant on LA’s Sunset Strip for $10 apiece, this delirious piece of sex magick infused psychedelia is generally considered the best of their nine albums, and one of the furthest out psych-rock records of all time. Recorded in their own specially adapted rehearsal room at Father House in the Hollywood Hills, a converted garage adjacent to where their morning meditation took place, listening to it with full attention is like eavesdropping on some intensely private, arcane ritual taking place outside of linear time.

Driven more by their daily practice of karezza (meditative, gentle sexual intercourse without orgasm) and a fully embraced love and respect for nature than by their modest drug use – a single inhalation of marijuana smoke held for six-seconds every morning – Ya Ho Wha 13’s music was a direct expression of their desire for spiritual liberation through the medium of sensual pleasure. This in itself made their mystical philosophy fairly unusual, as such intense somatic states were more usually seen as a barrier to spiritual illumination than a spur to its progress. Father Yod (born Jim Baker) was concerned with the creation of heaven for himself and his followers in the present moment and not in some hypothetical future afterlife setting. Adorned in white robes, a silver pentacle around his neck and a silver buckle engraved with the astrological symbol for mercury on the belt around his waist, Baker appears in mid-chant on the album’s cover, the first word of its title spelled out in bullets – itself more of a sign of the family’s fears of what was occurring in the world around them than any reflection of any personal, violent intent.

Given all of that, it might be supposed that this album is composed of the kind of drippy, new-age piffle that gives crystals and dolphins a bad name. Not so. Consisting of four parts, the album begins very quietly, Baker intoning Yod He Vau He – the four letters of the Tetragrammaton, the four-letter Hebrew name of God – against Djin Aquarian’s initially spare, chugging guitar work, which picks up pace around the halfway mark before lurching into full on distortion amidst martial drumming as it draws to a close. Baker’s spacious kettle drum initiates the second track, gongs resonating and percussion pulsating hypnotically as wildly harmolodic guitar lines stretch out into infinity. ‘Journey Through An Elemental Kingdom’ is all spooky bells and bowed string drones for its first six minutes, before the drumming slowly falls into place, turning it into something more akin to Tony Conrad and Faust’s epic shamanic trance suite Outside The Dream Syndicate. Final track ‘Ya Ho Wha’ utilises Baker’s eerie theremin-like whistling to great effect before climaxing in distorted, amplifier valve-threatening chaos. Although none of their other albums come close to this one in terms of their effects on the listener, the Savage Sons Of Yahowa and I’m Gonna Take You Home are both also worthy of investigation for anyone interested in further exploring this unique axis of hedonistic spirituality and psychedelic rock music. Sean Kitching

Floorplan (Robert Hood) – ‘Never Grow Old’

Robert Hood’s music stands alone in his field; you won’t quite find its particular atmosphere and blazing energy replicated anywhere else in techno. It’s born of Hood’s faith in both his God and his music; that elemental force unique to his tracks, sufficient to sweep you right out of yourself on a dancefloor, is the sound of total focus and conviction. For the purposes of this list it would be easy to select one of many Hood tracks from the Detroit native’s long discography. In sleevenotes he has suggested that his faith was central to his musical practice as early as 1994 landmark Minimal Nation, and far from the museum piece often implied by the notion of a ‘seminal’ record, that album remains a joyful, highly charged experience. But in the end I went for something more recent – last year’s ‘Never Grow Old’, a reframing of Aretha Franklin’s 1973 gospel record of the same name, taken from Paradise, Hood’s first album as Floorplan.

That side project, he said in an interview with the Quietus last year, began with "a vision in the middle of the night. I was lying in bed and I was awakened by a premonition about using gospel music in stripped-down techno. Infusing the essence of holy music with disco, coupled with techno." His treatment of his source material is particularly exquisite here: tiny eddies of piano, amplified vinyl crackle, the gleeful hubbub of the live crowd present in the backdrop of Franklin’s recording, all set in graceful orbit around a deliriously banging two-note techno stomp. It gathers velocity as it plays, working itself up into ever-greater heights of spiritual fervour, less passing through dance music’s typical peaks and troughs than continuing to ascend, higher and higher, until the intensity becomes almost unsustainable, and you imagine for a tantalising moment that the music will simply tear through the fabric of the world itself, taking you and the rest of reality along with it. Matching lyrical sentiment to sound, ‘Never Grow Old’ connects the Christian promise of life everlasting to the eternal now of rave ecstasy, to complete immersion in the moment and momentary loss of the self. It’s a beautiful thing, alive and livewire, surging with spirit. Rory Gibb

Alim & Fargana Qasimov – ‘Ey Encanlar (Tears Flow From My Eyes Like Rain)’

The more you look into the Azerbaijani mugham musical tradition, of which Alim Qasimov is considered the foremost exponent, the more it defies easy encapsulation. It’s largely improvised, yet within strictly defined modal and melodic sequential systems. It’s an ostensibly secular music, yet has deep religious roots, with much of Qasimov’s work based on texts from the ghazals of the progressive Islamic poet Seyid Azim Shirvani. Indeed, ‘Ey Encanlar’ was composed in tribute to the then recently deceased singer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, legendary master of qawwali, the devotional music of the Islamic Sufi tradition.

Like the Sufis, Qasimov sees music as a means of profound transcendence – as the realisation and expression of hal, a meditative state in which the soul achieves a spiritual awakening. As your tediously stereotypical Western atheist, I’m remote from and scarcely understand these traditions. But I’m nonetheless deeply moved by the power of Qasimov’s music, by its fluidity and intensity, its unbelievable virtuosity and its sheer emotional force, its honesty and openness. There’s an elusive sliver of space between the spontaneity of inspiration and the formality of studious intellect that has a potent but curiously ineffable quality. It’s here where this music resides. Were I to look for some kind of deity, this would be a good place to start. Matt Evans

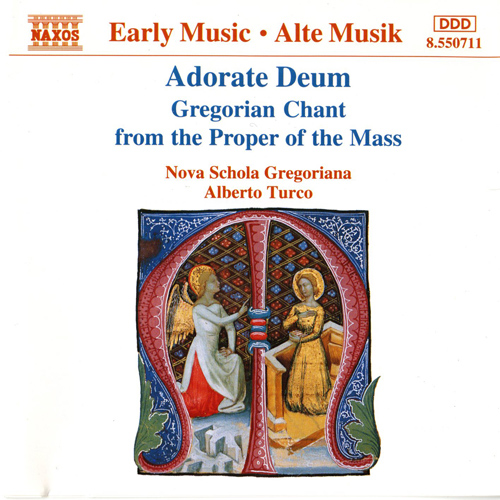

Nova Schola Gregoriana – Adorate Deum: Gregorian Chant From The Proper Of The Mass

Sung in Latin and entirely a cappella, Gregorian chant is sacred choral music which takes its name from Gregory the Great, who is believed to have regularised the disparate forms of Christian chant in the 6th century. The chant still has a function in the Catholic liturgy today, being used in sung masses and monastic divine offices, and such a modern rendering can be heard on the 1993 Naxos release Adorate Deum: Gregorian Chant From The Proper Of The Mass, performed by the Italian ensemble Nova Schola Gregoriana at the Church of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Mantua, whose acoustics are essential to the recording.

Although claimed by New Agey electronica in the 90s, notably in Enigma’s ubiquitous ‘Sadeness (Part 1)’, Gregorian chant itself remains highly effective (and affecting) music. Its absence of meter creates a transcendental, ethereal, almost hypnotic effect, fitting for its original purpose of religious devotion and mystical contemplation – qualities it also shares with much modern ambient music. The rendering of ‘Da Pacem’ on Adorate Deum, for example, has something of the opening of Badalamenti’s ‘Laura Palmer’s Theme’ from the Twin Peaks soundtrack. Gregorian chant works on the generalities of atmosphere rather than the specificities of emotion, evoking Eno’s statement on the sleeve of Ambient 1: Music for Airports (where ‘2/1’, comprising only a looping, wordless vocal, clearly echoed Gregorian chant): "Whereas conventional background music is produced by stripping away all sense of doubt and uncertainty (and thus all genuine interest) from the music, Ambient Music retains these qualities." While in its original context Gregorian chant conveys the certainty of religious faith, outside of that setting its esotericism and lyrical unintelligibility gives it the essential vagueness that creates space for reflection. Sophia Deboick

Count Ossie & The Mystic Revelation Of Rastafari – Grounation

This album is essentially a live album; a recording of a Nyahbinghi ceremony of drumming, chanting, poetry and singing, and is probably an ideal example of the nexus between the religious beliefs of Rastafari and the pop culture of reggae. And while this is clearly a spiritual album, the group The Mystic Revelation Of Rastafari featured a rolling cast of musicians of fearsome ability such as Tommy McCook, Lennie Hibbert and Don Drummond, while this triple album features the evergreen pop song ‘Oh Carolina’. John Doran

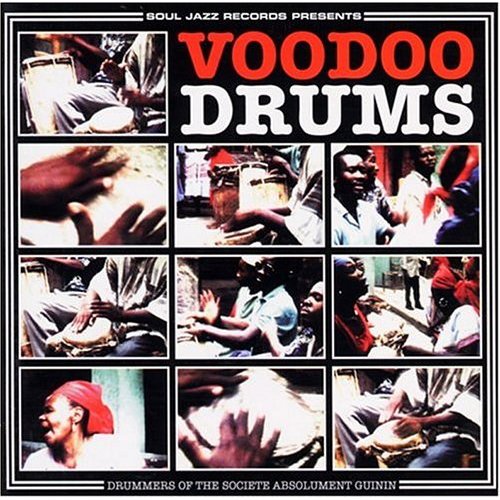

Drummers Of The Societe Absolument Guinin – Soul Jazz Presents: Voodoo Drums

This record, which consists entirely of recordings of voudou drumming made in Port-Au-Prince, is one of a series of Soul Jazz releases exploring Haitian music, all of which are worth your attention. Nonetheless there’s something about the intensity and virtuosity of this particular drums-based album that’s particularly transportive. Beautifully recorded so each strike of each drum punches with all the force of an electronic dance music kickdrum, it captures the extraordinary complexity and sophistication of these ceremonial rhythms, which shift, interlock and switch angle of attack with a logic that’s near-indecipherable as a listener unable to see visually how they unfold. These drum rituals are central to Haitian voudou, whose roots lie in closely related religions on the West Coast of Africa, and which originated in the 18th century when Haiti was a French slave colony. Their roles in ceremonies seem as complex and detailed as the rhythms themselves, involved in drawing participants together through the shared pulse of the beat and inciting spiritual possession. Yet their power to awe and mesmerise isn’t dimmed through being relatively unfamiliar with the traditions that underlie them; these recordings are dynamic and riveting in their intricacy and power. Rory Gibb

John Coltrane – A Love Supreme

The path to enlightenment clearly isn’t painless or plain-sailing. John Coltrane understood that only too well. In the liners to his gift-to-God, 1965 landmark recording A Love Supreme he wrote, in a kind of prayer: "No road is an easy one, but they all go back to God". Appropriately, Coltrane’s magnum opus, which deserves a space in every discerning music fan’s collection, can initially be difficult to penetrate. Coltrane’s blistering "sheets of sound" appear intimidating at first; pianist McCoy Tyner’s fourth chords sound abstract, and drummer Elvin Jones’ skittering free-jazz rhythms are difficult to get a handle on. But when it all clicks, it’s simply divine.

Coltrane was born and raised into a devout Christian family in North Carolina, but his renewed spiritual and musical transformation began in earnest in 1957, after a religious experience led him to kick heroin and alcoholism. A Love Supreme, then, was his personal declaration of his faith in God. It was written quickly, in a mere five days, after Coltrane cloistered himself in an upstairs room in his house with just a piece of paper, pen and saxophone. When he later re-appeared, his wife, Alice, noted: "It was like Moses coming down from the mountain". His declaration is most exquisitely embodied in the album’s fourth movement ‘Psalm’, where he ‘plays’ the words of the reverential poem he wrote for the original liners. Buy a copy, follow the words as Coltrane sings, and experience one of music’s most unforgettable spiritual moments. Jamie Skey

Grave Miasma – Odori Sepulcrorum

For many outside of the scene itself, the idea that any metal album could contain not just elements of genuine spirituality but could be born of a serious understanding and respect of ‘spirituality’, in its deepest, broadest and perhaps most abstract forms, is going to be a pretty thorny pill to swallow. That such an album has been created by a London based occult death metal band that for the first six years of their existence went by name of Goat Mölester is perhaps, then, a particularly blasphemous suggestion.

And yet here we, and here Grave Miasma are too. The perception is, of course, that death metal in particular treats death and the occult simply as a tool for cheap shocks: "dude, we draw stars upside down, get drunk and listen to metal!" etc – I don’t know Cannibal Corpse personally, but I’m fairly positive that neither ‘Skull Full Of Maggots’ or ‘Staring Through The Eyes Of The Dead’ are particularly spiritually inclined ruminations on the practices and historical philosophies of ‘death’. (Not that that matters especially). Not so with Grave Miasma, who with last year’s debut album Odori Sepulcrorum created something that whilst musically owing as much to the caustic, under-produced and relentless maelstrom of early Morbid Angle and Incantation as it does to the experimental bent of the likes of Portal, is also interwoven with a clearly obsessively studied aesthetic concerned with the various chronicled practices of the occult and death. That the quartet manage to incorporate sitars and Tibetan gongs too might seem cliché, but rather than simply wash them over intros or outros they’re masterfully suffused into the blistering chaos, most brilliantly during the unstoppable ‘Seven Coils’. Maybe experimentation, then, is the practice of death. Toby Cook

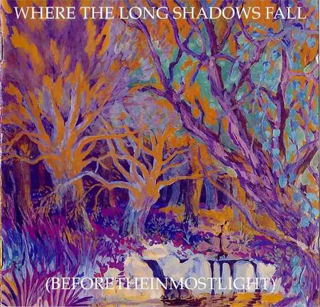

Current 93 – ‘Where The Long Shadows Fall (beforetheinmostlight)’

There’s no shorthand for David Tibet’s complex, allusive myth-world. Drawing connections between Noddy, Charles Sims and the Groundhogs alone, even while ignoring the hundreds of sacred texts, esoteric artists and under-sung authors he’s also evoked, would be a madman’s folly. But for the purposes of this article let’s laud him as pop’s finest outsider Catholic. A nineteen-minute sway built from a vocal loop, blurs of delayed guitar and altered choral interjections, this one could seem deceptively simple at first. But the loop is of Alessandro Moreschi, the ‘last castrato’, singing the word "Domine"; ‘The Inmost Light’ was one of Arthur Machen’s finest weird tales; and Tibet’s soft, mesmerising sermon promises unending mystery. It feels as if we’re actually in the numinous place his more overt songs can each only open a door toward. Lee Arizuno

Nikhil Banerjee – Ragas For Meditation

In 2010 I was hugely enamoured by one-time Vetiver guitarist Kevin Barker, and his solo album You & Me. The press photos for the record showed him sitting in his home surrounded by a vast collection of vinyl, and one in particular with its front cover on show: this hypnotically beautiful recording. Intrigued by the artwork and the record’s title, in the next few months I became an avid fan of Nikhil Banerjee. Consensus has it that Banerjee is at least the equal of Ravi Shankar as a sitar master, without embracing Western exposure to quite the same degree. Ragas For Meditation was recorded in 1969 and consists of two long ragas, ‘Bhatiyar’ and ‘Hemant’ – the former a morning raga, the latter a night raga. ‘Bhatiyar’ in particular is a staggering, moving piece of Indian classical music. Indeed, attempting to meditate to either raga can be a challenging business, as this is music your mind can’t help but pay attention to. ‘Bhatiyar’ is unexpectedly playful and hugely melodic, and when Ieramatullah Khan’s tabla joins early in the 25-minute piece, it is true electricity that does not beget calmness. Vinyl copies now do the rounds on Ebay. Barnaby Smith

The Pipes & Drums & Military Band of The Royal Scots Dragoon Guards – ‘Amazing Grace’

I’m not particularly religious. Never really had the drive to be so. I don’t know whether it was anything to do with not getting christened, whereas my four older sisters had been. I’m not sure if that has played a part in it. If having some water thrown at your head somehow makes you feel more akin to an idea or a feeling, then go for it. I’ve seen enough in my life to realise that God and his people move in less mysterious, more downright confusing ways. When a friend suddenly died last year, in a life too short to even counter the idea of how he wanted to be buried, knowing he was into Buddha and meditation, and then seeing him traditionally buried in a church graveyard, made me wonder if anything meant anything anymore anyway.

My Dad loved this tune. When I was old enough to rifle through the family record collection, there was a copy of this single (my Dad liked his music, and the likes of Klaus Wunderlich, Joe Loss, James Last and military bands were quite handy presents for Father’s Days and birthdays and Christmases). Being only about six, I wasn’t that interested in it, but when I started to learn about the charts, discovering that this spent five weeks at No.1 in 1972, between Nilsson’s Without You’ and T-Rex’s ‘Metal Guru’, pretty much blew my mind. ‘Amazing Grace’ just sounded a bit torturous and creepy, in a way, the hovering stillness of the arrangement making it sound almost ambient drone. It signified to me death and loss and the march of time. I couldn’t listen to it at all. But my Dad did. He’d retreat into the front room and play his music of an evening. Vibrating through the house with the bass distorting.

When I started to learn how to play the organ myself, one of the first tunes you learn is ‘Amazing Grace’. My mum and dad had spent a small fortune on a colossal monolith of a Hammond organ, the year all my mates were getting Casio VL-1s, and so whenever I’d practice in the evening, my Dad would come into the front room and make requests from my burgeoning repertoire – ‘Goodnight Sweetheart’, ‘I Love You Because’, the Hovis theme – and I would have to play ‘Amazing Grace’ at least three times. Obviously being a twelve year old who wanted to get back into his room and play his tapes, I didn’t regard it as cool or anything. I found quite dull really, if easy to play.

When the organ club held little concerts, my teacher wanted me to play my best stuff to the others, and an audience of their families and friends. ‘I Love You Because’ was one of my surefire winners, as was ‘Amazing Grace’. My Dad would drive me and my mum to the recitals, but would never actually come in. Preferring to wait in the car. I was a bit miffed by this, seeing as I was essentially doing all this for him. Then later during the evening, out of the corner of my eye, I would see him standing at the back, watching me play. Quietly proud of his son.

When he died in 2000, and my sisters and I were discussing music for his funeral, we agreed on ‘Amazing Grace’. There had been talk of ‘My Way’, but that was the undiscussable to me, being a sort-of get out clause for anyone who may have been a total shit in life to absolve themselves by saying they did it their way. There was no way I could’ve played it myself – the whole service seemed to blur with the tears, and I was grabbing my Mum’s hand tightly, trying to support her. I couldn’t cope when it came on, as again it seemed like a symbol of an ending, of times passing and the security, innocence and happiness that was being chipped away.

I’m still a bit weird when I hear it now. But then I remember my version being more subtle and less bagpipe-y, and groaning "oh DAD" and rolling my eyes when he would ask me to play it. Of course now I’d dearly love to be able to do it for him again. Ian Wade

Wardruna – ‘Heimta Thurs’

‘Pagan’ is a much-abused word in contemporary music, stripped of all meaning by various wally artists wafting around in a diaphanous cloak, getting a shit crow tattoo, and having a mutter about druidic forces. Norway’s Wardruna, though, are arguably more sincere. Featuring Mr Gay Bergen, Gaahl of Gorgoroth and his former bandmate Einar Selvik, Wardruna have released two albums based around interpreting the 24 runes of what’s known as the Elder Futhark. Far from their black metal roots, this is instead a potent folk music, created using field recordings from places pertaining to the runes themselves – forest, water, etc – and instruments recreated by master craftspeople, and based on ancient drawings and texts. Gaahl told the Quietus that his approach to Wardruna is more spiritual than archaeological, saying "My main source of knowledge comes from what runs through me. I’m trying not to be affected by things that are written – I have of course read a lot on this, but I try and approach Wardruna in a more meditative way, approach the runes with feelings rather than logic." We can of course never really know what music the ancient peoples of Scandinavia might have used to accompany their rites (much of what Wardruna use as source material comes from texts written only a few hundred years ago), but this feels like a creditable attempt to pay respects to the dark incomprehensibility of landscape and a pre-Christian past. Luke Turner

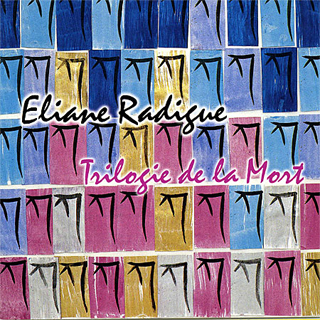

Eliane Radigue – ‘Trilogie De La Mort’

Eight years in the making, three hours in the listening, Trilogie De La Mort offers a uniquely perceptive take on that Technicolour funerary text, The Tibetan Book Of The Dead. It might seem an odd choice to render its elaborate lightshows and monstrous deities as a series of minimal electronic tones that fluctuate and transform with incredible subtlety. But Radigue was a practising Buddhist with an instinct for the message running through the book’s cosmic game of chicken: more or less "don’t get attached to any of this, and don’t freak out". Its drones maintain a total connection, holding small details and sublime emotions in ambiguous balance. After the final part, ‘Koume’, peaks with what feel like fanfares announcing rebirth followed by near-silence, you’ll want to go one quieter and meditate yourself. Lee Arizuno

Kirk Franklin – ‘Stomp’

On last year’s Trap Lord, one couldn’t help but notice the multiple references A$AP Ferg made to Donnie McClurkin, the New York-based minister and gospel singer. Yet those who paid closer attention to the self-described hood pope’s lyrics on ‘Murda Something’ were bound to come across the line "All my people say ‘Stomp’ like I’m Kirk or something". Though Ferg was likely no older than nine when he first heard it, clearly urban contemporary gospel artist Kirk Franklin’s album-length collaboration with the Dallas-based God’s Property Choir made an impression on the boy. (No stranger to rap attribution, Franklin has been namechecked in bars over the years by Cam’ron and Kendrick Lamar, among others.)

‘Stomp,’ that record’s remixed lead single, was a rare piece of overtly devotional music to climb the secular side of Billboard’s urban charts. A crossover hit with a music video that aired on MTV, the track made 1997’s God’s Property album a multi-platinum sales success, solidifying Franklin as one of the biggest names in Christian music. That’s no accident; the beat sounds like 1996, features Cheryl Jones (aka Salt from Salt-N-Pepa), and neatly encapsulates a sometimes controversial tack within Protestantism designed to connect with and evangelise to a wider audience. Still, ‘Stomp’ is the sort of feel-good, supremely soulful song that, regardless of your faith or lack thereof, that would be welcome in any throwback 90s hip-hop and R&B set. Gary Suarez

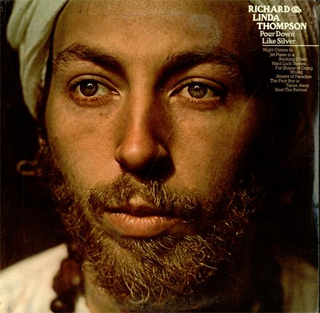

Richard & Linda Thompson – Pour Down Like Silver

Many see 1975’s Pour Down Like Silver as the third in Richard and Linda Thompson’s golden trilogy of albums, following I Want To See The Bright Lights Tonight (1974) and Hokey Pokey (1975). The former was their wonderful debut as a duo, full of typically exquisite songwriting, the second a more curious, misanthropic work that musically, with its inspiration from music hall and novelty songs, verged deliberately on the ridiculous. By mid-1975 and the recording of Pour Down Like Silver, the Thompsons were firmly entrenched in the Sufi faith, and following the making of the record would leave music behind entirely to live on a commune in East Anglia. On Hokey Pokey, Thompson’s Islam manifested itself through his apparent deflation at the grotesque excesses of those around him in the mid 70s, rather than anything more devotional. Pour Down Like Silver, however, is far more personal and with a marked emphasis on the couple’s dogma. Songs ‘Dimming Of The Day’, ‘Night Comes In’ and ‘Beat The Retreat’ seem explicitly addressed to god, representing more of a focus on what the Thompsons were embracing, rather than what they were disgusted by. Perhaps because of his increasing spiritual immersion, some of Richard Thompson’s most soulful, passionate guitar playing can be found on this album. Barnaby Smith

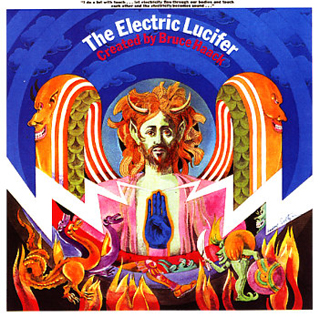

Bruce Haack – Electric Lucifer

It’s strange that one of the most level-headed explorations of actual Satanism wasn’t carried out by a black metal band, but by a children’s composer from the 1960s and 1970s. Of course, it didn’t hurt that Haack was an extremely forward looking, open minded musician who built his own synths, experimented with electronics and made muisque concrete outside of his day job. This album was made after Haack was introduced to acid rock, and he applied the techniques of the psychedelic era to his own outlier pop. Electric Lucifer is a concept album about planet Earth getting caught in the middle of a war that rages between Heaven and Hell. Late in the story he introduces his concept of ‘Powerlove’ – a force so strong it can redeem even the Great Horned One himself. So what is this LP? An album about Satanism or an album about Positive Humanism with an occult edge? Well, advocates would argue that they are one and the same thing, and that you should stop thinking in such a binary Judeo-Christian way anyway… Hail Satan! (He just needs a cuddle…) John Doran

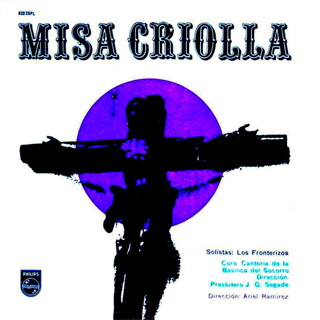

Ariel Ramirez – Misa Criolla

Keep an eye out next time you’re digging through the LPs at Sue Ryder, because among those decaying copies of Herb Alpert and Mantovani, you may come across this arresting little gem. Following a ruling by the Second Vatican Council in the early 1960s, Ariel Ramirez’s Misa Criolla was one of the first masses to be written in a modern language. Not only did Ramirez compose his mass in Spanish, but he combined influences and instruments from around the Latin American folk tradition to create a truly unique piece of work. From the stately chorale of the ‘Kyrie’ to the expansive, jubilant chacarera trunca rhythms of the ‘Credo’, Ramirez’s mass spans a range of emotions over its short runtime. With few moments that could be classed as anything less than startling, the Misa Criolla is enough to make even the most un-enlightened listener stop and pay attention. It has been recorded a number of times since its inception, but I’d especially recommend the version performed by Los Fronterizos and the Argentine Choir of the Basilica del Socorro. Charlie Frame

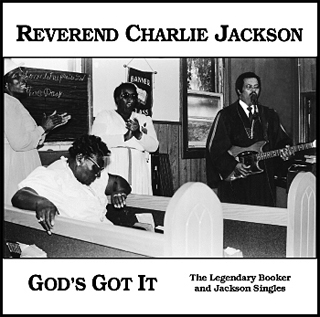

Reverend Charlie Jackson – ‘God’s Got It’

Rev. Charlie Jackson (1932-2006) was without a doubt one of the all-time greats of American gospel guitar. With neither the gruff voice nor the lightning guitar chops of John Lee Hooker, he nonetheless chose to praise Him through the medium of rough-edged blues boogie. His voice often sounds on the verge of total self-destruction, such is his aggressive delivery and commitment to spreading the gospel. Frequenting churches up and down the Mississippi for most of his life, Rev. Jackson was known for his ability to woo congregations into a stupor with off-the-cuff interaction and uproarious energetic jams, with crowds often supplying hypnotic impromptu 4/4 handclaps and footstomps behind the Rev’s swampy guitar runs. The title track from this 2003 compilation of lo-fi recordings made during the 1970s sees Jackson declaring "God’s got it" with such vigour that it’s pretty tough to argue. Tristan Bath

John Zorn’s Masada – Live at Tonic 2001

There can be little doubt that John Zorn is one of the most prolific, talented and stylistically diverse composers of his (or any other) time. Although he is probably best known for his punishing performances in groups such as Naked City and Painkiller, he appears as either composer or performer on several hundred recordings crossing innumerable genre boundaries. With his own label, Tzadik, Zorn has done more to explore the connections between symbolic mystical systems – including his own Jewish heritage as well as more occult based paradigms such as Aleister Crowley’s Thelema and 17th century astrologer/mathematician John Dee’s Enochian language – than any other musician I could name.

Taking its name from the ancient fortress in the Southern District of Israel on the eastern edge of the Judaean Desert, Masada is Zorn’s title for his ‘songbook’ of over 500 brief compositions, written in accordance with a set of specific rules, and inspired by his desire to combine the music of Ornette Coleman with the scales of traditional Jewish music. To listeners only familiar with the incendiary style exhibited by Zorn on albums such as Naked City’s Grand Guignol, the immediacy, beauty and spaciousness of some of the tunes on this live album – recorded at Tonic in New York’s Lower East Side in 2001 – could come as something of a surprise. The history that provides the inspiration for this music may be born of cultural genocide and considerable carnage, but it’s one which has contained strong creative, spiritual and community values as a reaction to those events. Performance wise, the band are on incredible form, with Zorn himself on saxophone, Greg Cohen on double bass, Dave Douglas on trumpet and the always incredible Joey Baron on drums all having spent much of the previous decade honing their craft with their studio recordings. Highlights are almost too frequent to mention, but seventeen-minute opener ‘Karaim’ with its complex interwoven melodies and wonderfully rolling drumbeats, the intensely cool downtown NYC beats and stratospheric sax of ‘Ner Tamid’ and the propulsive bass and percussion driven epic journey of ‘Lillin’ rank highest among my personal favourites.

Given the esoteric element inherent in Zorn’s Jewish heritage – for example Gematria, the system of interpretations based on the numerical values of the Hebrew alphabet, or the complex reality-encompassing filing system known as the Qabalah – it is perhaps unsurprising that someone with his restless inquiring spirit would turn in time to exploration of other occult systems. When I bumped into him on the Lower East Side street where I was staying in NYC for my fortieth birthday in 2009, Zorn seemed surprised to be recognised by a vacationing Brit. I was less surprised myself, but only because I had heard that he lived in the area, and had seen him performing a few weeks previously alongside the ritualistic master of percussion Z’ev at the occult-centric Equinox festival in London. For anyone with an interest in such matters, synchronicities such as these are the very spice of life. Sean Kitching

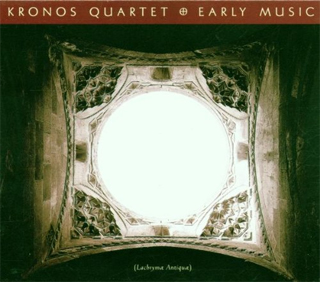

Kronos Quartet – ‘Perotin – Viderunt Omnes’

It starts with a perfect fifth and a lilting melody that sways like dancing clouds in a limpid sky. At 11:47, ‘Viderunt Omnes’ is the longest track on Kronos Quartet’s 1997 Nonesuch release Early Music by a good three minutes. Its history is at least as momentous: an adaptation for string quartet of Perotin’s 12th century polyphonic variation of an 11th century Gregorian plainchant. And yet none of this weighs it down – the recording is suffused with both light and lightness. Perhaps it’s because it’s all strings and no voice, perhaps it’s the tenderness of the arrangement, or perhaps it’s simply the grace these four exceptionally dextrous musicians bring to the piece, but it’s as if Kronos Quartet somehow manage to take this ancient discant outside – beyond the stone and the filtered half-light of the Gothic cathedral where it was born, and into the quiet above it. The intertwining melodies describe patterns as playful as a feather mid-air, lifted up and tumbled about, turning this way and that and looping back on itself. Even in those passages where intricate polyphony gives way to a single unadorned line, the path it follows is just as unexpected. The original Latin chant, taken from Psalm 98, is an open call for all the ends of the earth to celebrate, and this sense of timeless rejoicing underpins the music itself. If faith is the "spacious place" spoken of in Psalm 18, this piece is exactly how I imagine that space to feel. Dale Berning

John Tavener – ‘The Lamb’

Written almost effortlessly during a car journey from Devon to London in 1982 according to the late composer, ‘The Lamb’ realises the musical intentions of William Blake’s poem, published in the Romantic poet’s first collection, Songs Of Innocence from 1789. Tavener taps into the poem’s simple piety, setting up a comparison between the lamb and Christ over rhyming couplets, and sets each line within a gentle surge of melody, which is, depending on the performance, usually rendered in wonderfully heaving slowness. The opening bars ring out a delicacy fitting for Blake’s words, but as the voices mass, Tavener underlines the gravity of the poem with very slightly jarring harmonies, before the male choristers join, freighting the piece with the glorious heaviness of a requiem.

While its source is written in an 18th-century language of devotion – "Little lamb, who made thee?/ Dost thou know who made thee?" – the overall sonic impression Tavener makes is of something that feels like it exists outside of time, the lines’ rising and falling inflections simply sitting in space. The last time I heard the piece was at the beginning of Wild Beasts’ FACT mix, where its closing bars segue into the band’s own cover of Leonard Cohen’s ‘Hey That’s No Way To Say Goodbye’. The ease with which the tracks sit together points to Tavener’s brilliance in forging a piece that feels deeply emotionally affecting, no matter where you stand spiritually. Laurie Tuffrey

Constance Demby – Skies Above Skies

Though an evaluation of new age might now encompass the ropey aesthetic values of rainbows and unicorns, whale song cassettes and blokes in flappy trousers selling you healing crystals, its original virtue was in aiming to reconnect with common elements of spirituality that were pluralistic and intercontinental in breadth. In terms of musicality, the movement tended to draw inspiration from a diverse array of cultural devotional music. Indeed here, from 1978, Constance Demby’s Skies Above Skies is a central consolidation of a nexus of inspiration points, with focus coming from her particular involvement then in Sant Mat, a school of Indian teaching (or "…a discipline based on the yoga of mantra and the eternal Sound Current") which, when channelled into hymnal song, creates something rarely and startlingly heartfelt. The music is slight and sensitive – often using little more than her voice, the radiations of a hammered dulcimer and layers of cello to weave what she refers to as "prayers turning into song" – but the effect is profound and sublime enough to be revelatory again and again. One of the tracks, ‘Om Mani Padme Hum’, is was recently a particular highlight in the excellent re-evaluatory new age reissue I Am The Center: Private Issue New Age in America: 1950-1990, which hopefully means her work has found a few more listeners again. Matthew Kent

Crumbling Ghost – ‘The Old Way’

A reworking of an 18th century Primitive Methodist hymn via doom metal and Wicker Man folk – what’s not to love? London’s Crumbling Ghost may draw on paths pioneered by the likes of Agalloch and Chelsea Wolfe, but this version of a forgotten hymn is a revelation. It takes conventionally religious, unpromising lyrics ("Lift up your hearts, Emmanuel’s friends") and twists them, via horror movie drone, into something sinister. The kind of congregation who’d sing this version would be as likely to throw you onto a sacrificial fire to the fertility god as pray to the Lord for your immortal soul. I suspect next to no-one sings ‘The Old Way’ in Methodist churches these days, but Crumbling Ghost have achieved a rare thing – not only have they’ve offered a lost hymn a second life, they’ve revealed the hidden menace at the heart of English Pastoral. Rev. Rachel Mann

Ayahuasca Medicine Ceremony Song

I guess I’d always considered music and drugs to be important, yet recreational, pursuits until they united in a shamanic healing in Peru’s Sacred Valley in 2011. In a small temple in Pisac, thirty minutes from Cusco, I drank ayahuasca with a shaman called Diego Palma, while researching an article about shamanism. Ayahuasca is made from Amazonian plants, which combine to make the psychoactive compound DMT active, inducing lengthy internal meditations, usually with intense visions. In Peru, ayahuasca isn’t a recreational drug: it’s a medicine that’s been used widely for thousands of years. Shamans, who drink too, use it to deepen their connection with the spirit world, ascertain the source of illnesses or seek answers to people’s problems… though people often find those answers themselves, for better or for worse.

It was 10pm when, in turns, we drank the bitter brew from a soapstone cup, before crawling back to our pillows, vomit buckets and visions as palo santo smoke curled through the blackness. (Vomiting and diarrhoea are welcomed as part of the medicine’s work to expel parasites and negative energies.) This side effect also meant that after my visions had mostly ended – too vast, life-changing and terrifying to go into here – for the next two hours I listened to people laugh, sob and retch in the darkness, wracked by their visions – like dreaming whilst awake with no way to wake up – of heaven, hell and everything in between, but through it all I was anchored by Diego and his wife Milagros playing guitar and a shapaka (leaf rattle) as they sang icaros (medicine songs). Chants, mantras and folk songs, wistful inhaled rhythms and throat singing, in Spanish, Quechuan and English, held me as I flickered in and out of a spirit world like no other. Both deeply functional and deeply spiritual: never have I needed song so much. Live recordings of the medicine songs are here, but for me they belong embedded in the experience, and disassociated from it are bound to disappoint. Kate Hennessy

Dadawah – Peace & Love

"Without love, we are nothing at all," states Ras Michael in the final minute of Peace & Love‘s opening song ‘Run Come Rally’. Mantra-like, he repeats it, pauses to consider its significance then reiterates again, more firmly each time. Around him his band craft a music that breathes with as much depth of purpose as the players themselves: hypnotic, lulling patter of hand-played Nyabinghi drums, heartbeat throb of bass, and Willie Lindo’s awesomely free and exploratory blues guitar playing, almost unstuck from the rhythmic pulse containing it, looping languid through the air like wisps of smoke. Studio-assisted with effects from Lloyd Charmers and engineer George Raymond (who, according to the text accompanying the album’s reissue, stayed up all night after the session to mix it and heighten the mood), the group conjure up mirage images, shimmering landscapes of sun-scorched desert stretching to the horizon in all directions, sweat and toil, the burden of physical existence.

Michael is a guide of sorts through the album’s dazed, sprawling expanses, praising Jah and reflecting upon human suffering and the need for kindness, peace and unity. As with all the best roots reggae, his lyrics’ spiritual considerations are not simply matched by the music – they’re inseparable from it, with the group together conjuring up a world that’s deep and reverberant in sound, but also considerate and meditative, its tempo and energy level grounded in the pulse of the human body. The result is music that swallows you whole. Originally recorded and released in 1974 through Wildflower, I have Mark Ernestus and Mark Ainley of Honest Jon’s to thank for discovering this wonderful record (as I suspect did many other listeners) when they reissued it in 2010 through their excellent Dug Out label. As a result copies are easy to get hold of, and I strongly suggest you do so. Rory Gibb

Arvo Pärt – ‘Spiegel Im Spiegel’

Some have called Pärt’s music from the late 1970s ‘holy minimalism’, a term the Estonian composer apparently abhors in favour of ‘tintinnabuli’ (from the Latin for bell, tintinnabulum). There’s some truth in that first description: the essence of his music from that period is often so slight as to be almost absent, yet its potency to move is overwhelming, and thus it remains utterly mysterious. 1978’s ‘Spiegel Im Spiegel’ – eight minutes of sparse piano and violin tracing a melody whose simplicity and restraint are, quite honestly, transcendental – is one of Pärt’s finest compositions, but I can’t explain how it’s able to burrow deep inside me and provoke the extraordinarily profound sentiments it does. Some, including most likely Pärt, would ascribe this to God. Personally, I don’t need to. Being unable to comprehend its workings is exactly what makes it all the more awe-inspiring.

In a comment that recalls Mark Hollis’ belief that "I would rather hear one note than I would two, and I would rather hear silence than I would one note," Pärt once said that he wants his music to "express love for every note", and this is the way it sounds. (In fact, I often find myself thinking of Talk Talk’s Spirit Of Eden as being a distant relative of much of Pärt’s work at this time). In so doing, however, Pärt seems to express love for every single, tiny detail in our lives, with sadness and joy side by side, inextricably intertwined, useless without one another. Wyndham Wallace

Prince – ‘The Cross’

To my eternal damnation I’m not a religious person. At all. I’m a scientist by training and put my faith in what I can see and touch, and I live a life ruled by logic. But I’m fascinated by the concept of religion and at times envious of those who draw strength from their belief in a higher being. I’ve never felt the need to go to a church, mosque or synagogue and while I think Buddhism sounds rather groovy, I’m perfectly content in my personal spiritual vacuum. However, in April 1987, aged 16, I nearly underwent a conversion. I had locked myself in my bedroom to give a first play to Prince’s mighty Sign O’ The Times album, which had been released earlier that day. After three sides of the double album I realised I was listening to one of the decade’s greatest records, but it was the first song on the final stretch of Sign O’ The Times that blew my juvenile mind.

The track started gently. Over an acoustic guitar, Prince – sounding resolutely forlorn – sang "Black day, stormy night / No love, no hope in sight / Don’t cry, He is coming / Don’t die without knowing the cross." A lonely sitar then took centre stage and Prince upped the ante with talk of "starving mothers", and within four minutes and 48 seconds ‘The Cross’ became the closest I’d ever come to wanting to believe in God. By the time the acoustic strummings had been overridden by an apocalyptic storm of electric guitar – almost as if Prince had personally contacted The Lord and ordered a mid-song Armageddon as a defiant display of omnipotence – I was all for running out of my house to the nearest place of worship and demanding to be christened, ordained and circumcised. I was momentarily enlightened; if you only ever hear one Prince song, don’t die without knowing ‘The Cross’. John Freeman

Sharakan Early Music Ensemble – The Music of Armenia, Vol. 2: Sharakan

An album that instantly made me want to travel to Armenia. The basis of Armenian hymns is the expansiveness of the vocals; there is usually only one voice at a time on Sharakan, which reverberates through a minimalist backing of violins, flutes and woodwinds, allowing the soloists to fill the remaining spaces with their singing. There is a distinctly melancholic shade to these songs, not all of which are overtly devotional (although always based on the hymnal tradition), and which carry titles such as ‘My Heart Trembles With Fear" and "Lord Have Mercy’. These hymns feel timeless, as if based on musical traditions that pre-date the arrival of Christianity, and as such are steeped in mystery and enigma. Joseph Burnett

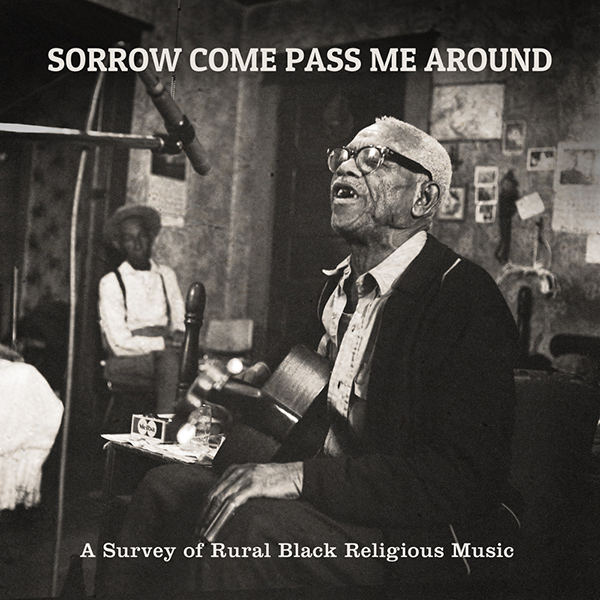

Various – Sorrow Come Pass Me Around: A Survey Of Rural Black Religious Music

The so-called "greatest LP of gospel field recordings ever produced" really does a lot to deserve its billing. The compilation first came out in 1975, having been recorded mainly by ethnomusicologist David Evans, with some help from other notables such as John Fahey and Cheryl Thurber between 1965 and 1973, across the southern states of America. (Dust To Digital put out a great reissue last year.) The songs benefited from being recorded mainly in domestic settings rather than during actual religious services at the request of Evans. They have an intense intimacy, given that most are just the unaccompanied voice or voices with guitars or banjos, and audibly recorded in small rooms. There’s just as much pleasure to be had in standards such as ‘Glory Glory Hallelujah’ and ‘When The Circle Be Unbroken’ as there is in relatively obscure material like ‘The Ship Is At The Landing’ and ‘Can’t No Grave Hold My Body Down’. An essential religious recording, regardless of the listener’s beliefs. John Doran

The Carter Family – ‘No Depression in Heaven’