The folk tales collected by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm in 19th century Germany have lost none of their power and symbolism down the years. In fact, repetition of the stories has merely strengthened their grip on the Western imagination; they were after all created through and for repetition, having been passed down orally through generations before being fixed in type by the Brothers Grimm. And the stories have continued to change and evolve since then, the mythic and psychological archetypes the brothers emphasised and embellished in the tales making them easy fodder for Hollywood blockbusters and nationalist propaganda alike. Walt Disney and Adolf Hitler were just two of the twentieth century myth-makers who successfully harnessed the seductive essence of the Grimms.

In 1971, the Grimm tales were taken up by the Pulitzer Prize winning American poet Anne Sexton, and were retold in verse form in her book Transformations. Sexton brought her knowing, half-ironic, late twentieth century tone to bear on the tales, a brittle, urban-intellectual, cosmopolitan voice that was midway between her two contemporaries Sylvia Plath and Dorothy Parker. Transformations was a smart, laconic re-telling that had picked up on all the Freudian, Jungian, Feminist and Marxist interpretations of the stories, absorbed them and come out the other side. The tales were held up to the cocktail party lights but then returned to the world of myth; their power still intact, but made relevant to the kind of early 70s New York hipsters who recognised themselves in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall.

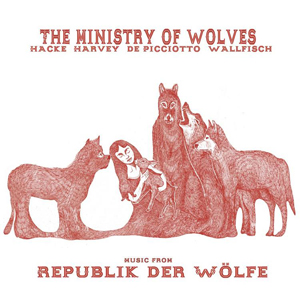

Sexton’s poems form the basis of this album, itself the soundtrack to a play inspired by Transformations and directed by Claudia Bauer for Theater Dortmund, described as "a fairytale massacre with live music." The theatre’s musical director Paul Wallfisch joins a trio of musicians whose common reference point is the elegantly gothic, post-punk aggregation Crime And The City Solution. Both Mick Harvey and Alexander Hacke were members of the band’s best known, European incarnation during the 1980s, while Hacke and his wife Danielle de Picciotto are both members of the current, Detroit-based line-up. Hacke was/is also a key member of Einsturzende Neubaten, while the American-born Di Picciotto is a veteran instigator of the Berlin art and club scene and a former singer for Die Haut, and is no stranger to theatrical multi-media performances.

De Picciotto takes lead vocals on the first number, ‘The Gold Key’, an introduction to the song-cycle that follows, in which she casts herself as a middle-aged witch and storyteller; warning us of the dark, mature and perhaps female / outsider perspective that will be brought to bear on these tales. Over a circular pattern of tremulous guitar and spare, thoughtful piano, adults are asked to recall being read to as children, and to willingly re-enter that half-forgotten space of imagination and terror. But they are also there to try to bring back meaning and significance to their present lives; the gold key of the title. "It is not enough to read Hesse and drink clam chowder," De Picciotto half-mockingly intones. "We must have answers."

‘Rumpelstiltskin’ immediately follows, tripwire tense like the horror-jazz soundtrack to a vintage noir thriller, chiming guitar and synth stabs clashing like gunshots over deep, rolling piano. Hacke growls like Tom Waits, presenting Rumpelstiltskin as the mean, vindictive freak within us all, a deformed dwarf that represents all of our worst impulses. Where ‘The Gold Key’ was a straight reading of Century Germany have lost none of Sexton’s poem, ‘Rumpelstiltskin’ takes greater liberties, cutting back the original to just the voice of Rumpelstiltskin himself and omitting the majority of the narrative, as well as period references to Truman Capote and Bond Street. The line "The devil told you that" is pulled out as a repeated hookline, and the result is highly successful, claustrophobic and menacing.

Sexton’s poems are used as source material to varying degrees throughout the record. The rhyming stanzas of ‘The Frog Prince’ lend themselves naturally to Harvey’s droning acoustic ballad, that shifts to a croaking, sinister piano chorus when the frog speaks: "let me eat from your plate, let me drink from your cup, let me sleep in your bed." The usual assumed moral of the tale, that we should refrain from judging by appearances, is ignored; the warty amphibian pest is presented as an unsympathetic and repulsive stalker, not to be kissed but (as in the original tale) thrown angrily against the wall. It’s then that he transforms into a handsome prince, but one who, in his jealous possessiveness, is little better than before.

‘Cinderella’ and ‘Rapunzel (As Isadora Duncan)’ are original pieces, inspired by but considerably departing from Sexton’s poems. In the former, De Picciotto breathily mocks our continued willing credulity for effortless rags to riches fantasies, as bought into with every hopeless lottery ticket. It’s another dark, languid waltz, with Leonard Cohen spiritually stood in the shadows; speeding up to near manic levels of wide-eyed excitement, before returning to reality’s slow, scornful two-step. Hacke’s ‘Rapunzel’ marries a spoken verse to a Bowie-esque chorus: "a woman who loves a woman stays forever young." Scrapyard drumming and dream-like harp passes set up a tension between cynicism and romanticism that accurately reflects the ambivalence of the lyrics. Odd images and lines are taken from Sexton’s poem almost as samples, to be used and re-positioned in a new piece of work. On the other hand, ‘Hansel And Gretel’ is a near-faithful adaptation, with Mick Harvey delivering every macabre variation on Sexton’s children-as-food theme with lip-smacking relish.

The fact that we all know – or think we know – these stories means that this theatrical soundtrack doesn’t feel like half an experience. We fill in the narrative and the visuals ourselves, and the songs are well-crafted enough to easily stand up in their own right. It’s not, incidentally, the first time that these poems have been adapted to music; Transformations was previously used as the libretto for a 1973 opera by Conrad Sousa, and Sexton also read her poems with a surprisingly funky jazz-rock backing band called Her Kind, though I’m not aware that any of these pieces were ever included in their set.

With fairy-tales there are no definitive readings; their mutability, the fact that they change to meet the needs of each succeeding generations, while staying essentially the same, is their greatest strength. But with this album, Ministry Of Wolves have done both Anne Sexton and the Brothers Grimm proud; bringing their own gothic legacy to bear, and returning their work to the dark forests where they belong.