Melville House is a rare thing amongst even the most powerful of its peers: a publisher that does a lot of things and, for the most part, does them all incredibly well. Simultaneously an avant garde-ist and a conservationist – very much an advocate of the present and staunchly dedicated to the preservation of the past.

Nestled neatly between the two and, perhaps, most impressive of all is its ability to predict the future – to find and foster talent of all sorts: a regular Brangelina. It is in this vein that the publishing house who, some seven years ago, for better or worse depending on still-much-discussed-and-continually-divided opinion, launched Eeeee Eee Eeee (the debut novel of New York’s literary enfant terrible, Tao Lin) upon the world, now gives us A Highly Unlikely Scenario and The Weirdness.

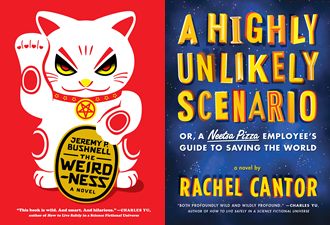

A million miles from the all-too-real austerity of Lin’s prose, Jeremy P. Bushnell’s The Weirdness and Rachel Cantor’s A Highly Unlikely Scenario – or, to give it its full name A Highly Unlikely Scenario: Or, a Neetsa Pizza Employee’s Guide to Saving the World – are, by all counts, sprawling romps through fantastical visions of vaguely familiar worlds populated with demons, totems, time travel and world-dominating fast food corporations. (Bushnell’s novel covers a struggling writer’s deal with the devil and subsequent quest to steal something like one of those cute waving cats that you see in the window of more-or-less every shop in every Chinatown in the world, and Cantor’s the coming together of a fast food complaint hotline manager from the near-future and an explorer, and whole host of other characters, from the distant past.)

They are, perhaps, candidates for the most appropriately-named novels in recent memory. And, while it may seem unlikely – Highly Unlikely, even – there is a Grand Unifier at play here: Cantor and Bushnell, like Lin over half a decade ago, are debut novelists of the highest order. By turns hilarious, bewildering and breathtaking in the scope of their imagination, the newest members of the Melville House family are a testament to its continued benchmark-setting for phenomenal new literary talent and to its prophetic abilities.

Rachel Cantor: Your main character, Billy, is an emerging writer who’s accused by a literary bad guy of stumbling "into the ravaged storehouse of tired forms and stale devices." But there’s nothing tired or stale about The Weirdness: the devil convinces Billy to retrieve the Neko of Infinite Equilibrium (the neko being one of those good-luck cat statuettes we see in Chinese restaurants) by promising him literary success. There are warlocks and the threat of world destruction through infinite heat. Billy smokes cigars with Lucifer at an Algerian creperie, for heaven’s sake. I love the imagination and humour of The Weirdness. Was coming up with all this invention as fun as I think it was? Was it important to you to have fun writing this book?

Jeremy P. Bushnell: In the drafting of this book I explicitly told myself that it was OK to have fun. "Fun," of course, being a relative term — I mean, when I’m writing what I’m doing actuality is spending hours at a time frowning at my computer, obsessively focused on a million little micro decisions — not really in the same category of fun as, say, spending a day playing video games. But with that said, what I really allowed myself to do in this book — what made it "fun" to write — was to write about stuff that felt crucial to my own lived experience, which has been a variegated and strange and kind of funny experience, I’m happy to say. So sometimes that meant writing about, I don’t know, Twitter, and sometimes that meant writing about German pyrotechnicians or Norwegian power electronics musicians or Algerian chefs, and sometimes that meant writing about the stock fantasy tropes that resonate with me, like a sorcerer in a tower or a guy making a deal with the devil. The freedom to embroider the basic plot armature with the particular and precise details that make up the world as I see it is what made it fun.

RC: Exactly! You wanted to write an adventure tale that’s fun, and the way you had fun is not just by adhering to, or even playing with, genre conventions but by following (I won’t say ‘indulging’) your literary, spiritual, intellectual, and I guess "real life" obsessions.

JPB: Speaking of genre conventions, when I first started hearing about A Highly Unlikely Scenario, I heard it described as a literary take on dystopian science fiction. As a fan of science fiction and literary novels I was like, that’s cool, sounds great! But before too long the book takes a time-travelish turn and becomes what one could fairly call a historical romp, featuring a cast of characters that ranges from the famous (Marco Polo, Roger Bacon) to the obscure (Zedekiah Anaw?). Did the choice to work with these characters derive from wanting to write something that involved time travel? Or was it the reverse: that you opted to write a time-travel book because you wanted to work with these historical personages?

RC: The characters came first; time travel necessarily followed. I knew that Isaac the Blind, the medieval father of Kabbalah, had the ability to read souls; some said he could also appear in two places at once. Because he was concerned that mystical secrets not be shared with the uninitiated, he had no choice but to travel both to the past and the future. Because saving the world turns out not to be a one-person job, Leonard also has to travel — in his case, to thirteenth-century Rome.

Your book is resolutely of our time, though, isn’t it? That’s one of the things I enjoyed about it: all those crazy things happening not in some distant future or alternative present, but on my turf. There are Starbucks (albeit in unlikely locations) and New York City traffic jams and roommates who get in the way of your sex life and literary blogs and, ugh, possibly under-attended readings. Were you ever tempted to situate your book in an unfamiliar or fantastic setting? Is this something you might want to do in future?

JPB: It was important to me that the parts of the book that weren’t fantastical be as realistic as possible. To a degree that’s because it creates interesting tensions with the genre elements, but to a degree it’s because I really do still love straight-up literary realism, and the trappings that we associate with it: a world that we recognise, populated by people with fleshed-out backgrounds and emotions that ring true. Some bad things happen in my book, and when my characters get hurt, I want it to matter. I had fun a few years ago making a sprawling science-fiction world in the form of a board game, Inevitable, and in that world people get killed or get driven insane and it’s all for laughs — but that type of world-building seems to be out of my system for now. (Come to think of it, there are corporate coffeehouses in that world, too.)

I think both of us appreciate that one doesn’t need to look to an alternate universe to find things that are striking or bizarre. This point is made, poignantly, towards the end of your own book when (spoiler warning?) your protagonist, Leonard, reflects on the "strangeness and wonder of the world." This really resonated with me: it’s what the "weirdness" in the title of my book refers to, and I feel like both of our books encourage readers to try to recognise and appreciate those strangenesses and weirdnesses. How do you do this in your own life?

RC: I love this question: it was this similarity between our protagonists that first struck me about your book. In the first scene of The Weirdness Billy gets distracted while looking for an ATM. He leaves his friend in a bar for twenty minutes because he’s thinking about bananas in the corner shop: who grew them, just how weird is it that we can walk into a shop in Brooklyn in the middle of November and buy bananas! Which causes him to think about the strangeness of commerce — and he’s off! So, yes, our characters don’t take reality for granted. I think your character, though, is more weirded out by the everyday: Leonard finds himself fascinated by the unfamiliar — the fantastical worlds Marco Polo describes to him in the first pages, or the oddities of the stronghold of the latter-day followers of medieval scientist Roger Bacon, or the magnificence of a medieval basilica inhabited by thousands of manic pilgrims. Coming up against these things that he never imagined occasions an awakening of sorts, which allows him finally to realise his extraordinary potential.

For myself, to answer your question, I think the practice of art — making it, appreciating I — contributes to a sense of wonder by helping us to see things new. Literature gives us a window into the unlimited otherness of other people; visual art allows us to see our surroundings — colours, forms, landscapes — differently. My book is light-hearted, but for me, experiencing this kind of wonder, this kind of appreciation, is a moral imperative. Do you cultivate the weirdness? Or is it something that comes naturally for you?

JPB: I remember, many years back now, when I was just beginning to identify as someone who wanted to be a writer, reading an interview with someone — I think it was Martin Amis. And Amis said that a writer was someone who needed to be able to look at the world and say "Wait— why cars?" That really struck me, although probably because I was a person who was already deeply puzzled by the opacity and mystery of the world — sometimes distressingly so — and it flattered me to think that this might, in some context, be considered a skill.

In my adult life, I’ve tried to move from being overwhelmed or paralysed by the mystery of the world to being appreciative of it, interested in it. And I felt a kinship with you there, because it’s evident from your novel that you have a real love of the varied things that make up the world.

RC: Wonder, and a willingness to hold and investigate the mystery of the world, is important to us as writers — we agree.

JPB: Yeah! I see this manifest in A Highly Unlikely Scenario in the way that it’s full of great, oddly specific nouns. You turn the page and you encounter a scramasax or a skirlie or a lakh or a fleeming or a necessarium. I never felt like you were deploying these nouns as a way to show off or make the reader feel dumb, though, quite the contrary: I got caught up in the palpable delight you seemed to take in them. Am I right in thinking that you want to get the reader excited about the very existence of these things?

RC: Thank you for loving my nouns. I sought out unfamiliar nouns (and I never thought about the fact that they’re all nouns) as a way of emphasising the strangeness we talked about before — the strangeness to Leonard of the worlds he must investigate and become a part of, and also the strangeness to us of Leonard’s world. Thus, when the Bad Guy fantasises about using various medieval weapons on Leonard, he speaks of the scramasax and brank and flail, and when the owner of the pilgrims’ hostel hard-sells Leonard on the advantages of his establishment, he uses words like necessarium. I’ve always loved the magic of words I don’t understand, even as a kid. What’s a sugar plum that it should dance in your head? Just how delightful is the Turkish delight in C.S. Lewis’s Narnia books?

JPB: I knew flail from my time spent playing Dungeons and Dragons, where it does 1d6+1 points of damage. But now onward, to the future. If I’ve heard correctly, Melville House UK is also putting out a second book by you, in 2015. Is this a sequel to A Highly Unlikely Scenario, or something different?

RC: It’s completely different. Briefly, it’s about an underachieving translator who hears, out of the blue, from a Nobel Prize-winning poet, who hopes she’ll translate his latest work, which is related to an early work of Dante, which she’d translated as a graduate student. She’s stunned, but of course agrees. Gradually, as the poet begins sending her pieces of this work, we begin to realise that he has another agenda, one that involves her personally. So the book shares A Highly Unlikely Scenario‘s obsession with medieval thinkers (in this case, Dante), but it’s set in a recognisable world – even if I have messed a little with the geography of Manhattan’s Upper West Side. What about you? I’m sure you’re busy with The Weirdness, but I have a feeling you’re working on another terrific thing. Give us a hint?

JPB: I’m about twelve chapters into a new novel, which is set in the same world as The Weirdness, although it has a different cast of characters and it is much darker. It centers around a butcher at a high-concept Manhattan restaurant, who is eventually put on a collision course with a bunch of malevolent individuals, including most prominently a European psychic who has the ability to discern the history of objects just by looking at them. This psychic ends up painfully aware of just exactly how much exploitation goes into just about everything that’s for sale anywhere, and it kind of cracks her ability to empathise with other humans. Fun stuff!

RC: Fun, dark stuff! Will you set your book on the Upper West Side, so maybe we can do this again?

JPB: Sorry: Midtown.

The Weirdness, by Jeremy P. Bushnell, is published 20th of March and A Highly Unlikely Scenario , by Rachel Cantor, is available now. Both are published by Melville House