In 1916, the Antarctic explorers Ernest Shackleton, Tom Crean and Frank Worsley were trekking across the glaciers and mountains of South Georgia Island in a last-ditch attempt to make it to the whaling station at Stromness. Having sailed through storms for two weeks, they were exhausted, starving and dehydrated. Edging around ravines in freezing fog and darkness, Shackleton became gradually aware of the presence of another person in their company, eerily walking alongside them. It remains unclear if the experience was due to hallucination, wishful thinking or, as some have suggested, celestial origin. The possibility of it being a diabolical presence was not generally considered. It’s a phenomenon which has affected mountaineers, aviators and astronauts. Psychologists call it the Third Man syndrome. As T.S. Eliot asked in ‘The Waste Land’, "Who is the third who walks always beside you?"

Being an inveterate coward, I am no explorer but in 2012, whilst living like a wretch in Phnom Penh, I wrote a study of the novels of an explorer of sorts, Jack Kerouac. Like many people, I’d read the Beats as a teenager but returning to their books after a decade was a strange and unsettling experience. Novels that had once inspired travel, hedonism and youthful abandon now seemed incredibly melancholic. On The Road, for one, seemed to be about loss and disappointment rather than friendship and adventure. The books had somehow changed as I had. During the process of writing the study, it appeared easy enough to work out the characters of the central figures of the Beat Generation. Kerouac was a bebopping hopelessly-alcoholic homoerotic mama’s boy (then there were his bad points), mistaken for a Beatnik when he fancied himself as a Catholic mystic. Despite all this, I ended up feeling sympathy for the poor deranged bastard by the end. By contrast, the poet Allen Ginsberg was an eminently likeable character on the surface but seemed to exist on the lengthy inertia that followed a brilliant initial burst (‘Howl’ and ‘Kaddish’ primarily), the indulgences of countercultural dilettantes and the vapours of Buddhism. There was however a third man in the peripheral vision, walking alongside like an undertaker to a duel, a man who the more I researched seemed to get further into the distance. Born before the First World War, he had cut his teeth in the underworld of 1940s New York and yet seemed perpetually five minutes in the future, to paraphrase J.G Ballard. El Hombre Invisible. Old Bull Lee. William Seward Burroughs.

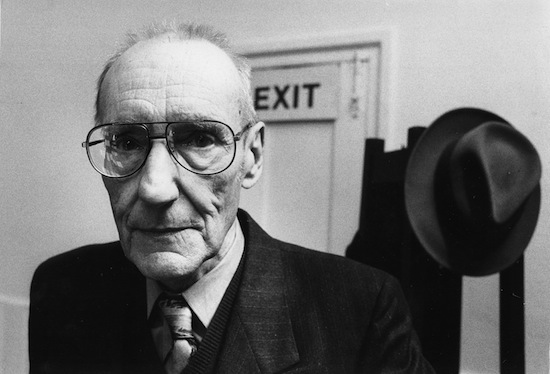

Who, or perhaps what, was Burroughs? He was a junkie for forty years by his own admission. He was a bug exterminator. He cut the top of his little finger off, claiming it was a Native American initiation rite. He studied at Harvard. He spent time in a series of hellhole prisons and psychiatric wards. He was queer, a term he preferred to gay (he loathed any suggestion of camp). He made arthouse films with Anthony Balch in the Sixties. He ventured off into the Amazonian rainforest to try the hallucinogen yage. He collaborated with Kurt Cobain on The "Priest" They Called Him. He tried to set up a farm in the Rio Grande valley. He once put a hex on Truman Capote. He’d lived in Nazi Germany and had saved the life of a Jewish lady, Ilse Klapper, by marrying and bringing her to the US. He shot and killed his wife Joan Vollmer at a party whilst drunkenly playing their "William Tell act”. He worked with Tom Waits and Robert Wilson on the Expressionist musical The Black Rider. He appeared in Gus Van Sant’s film Drugstore Cowboy. He collaborated with the artist Malcolm McNeill on Ah Pook Is Here, which was later made into a short film by Philip Hunt. He shilled for Nike. He released a spoken word album Call Me Burroughs in France in the summer of 1965. He was a member of the NRA who kept a loaded gun under his pillow, reputedly for fear of attack from, as he put it, ‘lesbians’. He lived in exile in Mexico, Paris, London and Tangiers. As an afterthought, he also wrote some books.

We run the risk of diminishing Burroughs’ books through attempts at explanation; they are there to be read and should be. Junkie: Confessions of an Unredeemed Drug Addict (1953) [later Junky] and Queer (written at the same time but published in 1985) are immensely enjoyable and hyper-perceptive pulp semi-confessionals, in the style of a modern De Quincey. Naked Lunch is a part-lucid part-fevered explosion of what a novel can do, without the charade of declaring itself experimental (it shows rather than tells). His Nova Trilogy (The Soft Machine, 1961; The Ticket That Exploded, 1962; and Nova Express, 1964) is possibly the furthest out-there he ever went, setting himself up as a Duchamp of the written word (inspired and assisted by the artist Brion Gysin) and attempting to create "a new mythology for the space age."His late Red Night trilogy (Cities of the Red Night, 1981; The Place of Dead Roads, 1983; and The Western Lands, 1987) remains underrated, reminiscent almost of Borges in scope (the stories roam in space and time) and reflexivity towards literary history. Genres are spliced and turned inside out, elements of noir, sci-fi, smut, Westerns, pirate adventures, Egyptian mythology and fantasy quests are thrown together. There are worlds in those books.

How could a man born one hundred years ago today still seem to speak so urgently and radically to us? The first reason is a stylistic one. Burroughs found a fitting way of representing the overload of our times. In abandoning the solely linear idea of narrative for cut-ups, he became an heir to the Modernists and did a great deal to close the fifty year gap he saw between literature and conceptual art. He was able to show that the increasingly ill-fitting structures of the Victorian novel were in fact the pretence rather than their experimental opponents as often claimed. After all, life and how we perceive it are neither entirely linear nor Dickensian. There was an honesty and a method in Burroughs’ apparent madness.

Just as books seeped into his life, Burroughs’ interests seeped into his books. Traces can be found in the most unlikely of places of his studies in anthropology, arcane literature, esoteric thought, the psychiatry of Wilhelm Reich, the semantics of <a href=”http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_Korzybski”target=”new”>Alfred Korzybski, Spengler’s Decline of the West, Mayan mythology, botany, libertarianism and archaeology. Lines and asides bubble up just as they do in consciousness. He admitted to "an insatiable appetite for the extreme and the sensational, for the morbid, slimy, and unwholesome”. He found these naturally in literature and passed on the knowledge at a time when obscurantism was rife in academia. He had his literary flaws of course but he had the good manners to make even his failures and minor works interesting (his dream journal My Education, his feline The Cat Inside and his collaboration with Kerouac And The Hippos Were Boiled In Their Tanks for instance). It’s not often said but Burroughs’ writing can be very funny, in the same irredeemably-bleak way that Beckett is (the two met briefly). The gallows humour was literal. They both found a source of amusement, for example, in the tendency of hanged men to have erections (‘angel lust’ as it’s been termed). In both cases however, a smile does not at any stage break their stern weather-beaten faces.

Ultimately, Burroughs’ books are their own advocates. Yet he seems much more than simply the sum of his writing. W.H. Auden once said of Jean Cocteau that his collected works would require not a bookshelf but a warehouse, given he had explored so many mediums. The same is true of Burroughs. It would require perhaps an aircraft hangar with a mattress on the floor, a paint-spattered firing range, an orgone accumulator, collages of film projected onto the walls, a typewriter scuttling across the floor, Sonic Youth emitting feedback in the corner and an old man sitting at a desk.

Another reason for the continual relevance of William Burroughs is that what haunted him is also what haunts us, whether we are aware of it or not. The bugs and the feds. Need and control. He is the Virgil of our glittery modern Inferno. The symbolism of his background is striking. Part of his childhood landscape was blown up by an atomic bomb when his Los Alamos boarding school was taken over by the Manhattan Project. His uncle Ivy Lee was the father of PR, initially for the Rockefeller oil and banking magnates (at the time of the Ludlow Massacre) before undergoing ruin in the thankless task of acting as Adolf Hitler’s U.S. spin doctor. Burroughs’ grandfather and namesake had patented the Burroughs Adding Machine, a device on the pathway to the computer age and whose advert, published in the year of his birth, seems to contain some of the conspiratorial unease that would follow in William junior’s work, "Why do so many businesses fail? After investigations covering twenty years, we have found scores of common reasons – ‘leaks’, neglected details etc”.

Following in their footsteps, Burroughs concerned himself with the insectile nature of society. He obliquely examined power, surveillance, coercion, shame, fear, excess and restriction, of how pliable and wilfully ignorant people can choose to be, of the psychopaths in charge, the fairytales we’re told to distract us and the morality, often self-administered, that hems us in. To Burroughs, it was all a question of manufactured need and control. He saw heroin, to which he was addicted, as a critical symbol, "Junk is a key, a prototype of life. If anyone can fully understand junk, he would have some of the secrets of life, the final answers…" In Ted Morgan’s biography Literary Outlaw, he elaborates, "The theory of addiction came into my head when the junk went into my arm. It was a metaphor for society. You start bending the word addiction out of shape and you see what it means. You can see withdrawal symptoms in the face of someone like Nixon, when the power ain’t there no more. Addiction means somethin’ that you’ve gotta have or you’re sick. Power and junk are symmetrical and quantitative." Burroughs was perceptive enough to see where this was leading – the very altering of the human being, "The junk merchant does not sell his product to the consumer, he sells the consumer to his product." It’s not unnoted that in the space of time between his writing this and now, we have gone from being citizens to consumers, almost without a gesture of resistance. It may only be language but as Burroughs repeatedly pointed out language isn’t just language.

Though Burroughs is an innately political writer, it would be a grave error to think of him as explicitly political. We could take a quote of his such as "A paranoid man is a man who knows a little about what’s going on" and apply it to the Snowden revelations for example but that is just the latest incarnation of a long-running problem. It has been before and it will be again. Kerouac hit on something when he claimed Burroughs was "the greatest satirical writer since Jonathan Swift." Like the Irishman, Burroughs could eviscerate indirectly, through allegory and without resorting to polemics. He was too much of a misanthrope or realist to hold much faith in the solutions offering by more dogmatic-types, seeing perhaps that in every revolutionary there is an inquisitor in waiting. At best, it was ignoring deeper, more pressing concerns. "To concern yourself with surface political conflicts" he said in a discussion for the Journal For the Protection of All Beings (1961), "is to make the mistake of the bull in the ring, you are charging the cloth. That is what politics is for, to teach you the cloth. Just as the bullfighter teaches the bull, teaches him to follow, obey the cloth." When his fellow Beat Gregory Corso asked him, "Who manipulates the cloth?"Burroughs replied, "Death." Take away that fear and you take away the control.

Burroughs could see that the issue was not simply the political or social macrocosm, it was the microcosm too. It lay in our heads. Puritanism is neurosis, outrage is obsession, control is fear. The modern world is not just sick, it’s poisoned and there are those who benefit greatly from administering both the poison and the cure. Burroughs’ clarity as to where the war on drugs and the need for drugs originates is not reassuring, "Every man has inside himself a parasitic being who is acting not at all to his advantage."We are partly the problem and we persist in shooting the messengers. Before his late canonisation, Burroughs was one such figure. Though censors helpfully point out the books we should be reading by banning them, their intention is not simply to restrict what is published but what it is possible to think. Through Naked Lunch and the resulting court cases fighting for its publication, Burroughs helped break the stranglehold on free thought, enquiry and expression. This was no small thing; at its simplest it’s the ability to write the word ‘fuck’ here and now and not find ourselves in court. His battle may have been won but it is a war which will always continue and should be fought, as he did, by advancing rather than in retreat.

There is a loathsome recent online trend for our favourite dead writers, a great many of whom were complex and difficult characters, to say nothing of their work, to be reduced to glorified self-help therapists ("What Susan Sontag can teach you about your inner child”) or creative writing tutors ("Ten awesome writing tips from the weeping ghost of F. Scott Fitzgerald”). Aside from my continued belief that Mephistopheles invented the listicle, the vacuous narcissism, spiritual horseshit and mercantile utilitarianism involved in such half-baked articles are sorry indictments of our times. This has led to reluctance on my part in acknowledging that any writer is or should be useful other than simply being free to write books. Usefulness is a censor’s way of thinking. Yet Burroughs, almost despite himself, is. Most obviously, he led by example in terms of what to do and what not to do. Long before Bowie (who he influenced with his cutup technique and subject matter), Burroughs, in a sense, wrote this life into existence. "The point is,"he told a Canadian press conference, "a writer can profit by experiences which would not be advantageous or profitable to others. Because he’s a writer, he can write about it." In his introduction to Queer, Burroughs makes the apparently brutally-honest confession, "I am forced to the appalling conclusion that I would never have become a writer but for Joan’s death, and to a realization of the extent to which this event has motivated and formulated my writing… The death of Joan brought me into contact with the invader, the Ugly Spirit, and manoeuvred me into a lifelong struggle, in which I have had no choice except to write my way out." Should we believe him? Did he believe himself? We might well ask these questions, not least on behalf of poor dead Joan, provided we accept that we’ve then cast ourselves as jurors rather than readers. "I’m creating an imaginary — it’s always imaginary — world in which I would like to live"he told The Paris Review in 1965.

A further way Burroughs might help is in rethinking the wretched binary nature of so much of Western civilisation. Since Aristotle’s De Interpretatione, we have been cursed by an either/or outlook that has led to virtually every discussion being framed in terms of false dichotomies. Often, all nuance, complexity and sophistication of thought is lost before a word has been uttered because of the framing of the debates. Everything that falls outside male/female, left/right, good/evil and so on is left to fall. You are with us or you are against us. A world of infinite shades of grey is portrayed as black and white. It is the continuing source of incalculable misery. "The mark of a basic shit" Burroughs writes in The Adding Machine: Selected Essays (1985), "is that he has to be right." Again, he suggests there is a control mechanism at work and it’s taking place in our heads. "A functioning police state needs no police" Burroughs pointed out in Naked Lunch, with the implication that the police are already installed in the minds and behaviours of the population. The source of its power is our insecurity, as pattern-craving mammals, when facing a world that is more unstable, complex and contradictory than we might like. It leads us to be susceptible to those offering reassuring infantile ways of explaining things, whatever their ulterior motives. Need and control. With most writers likewise urging us to aspire to dribbling childlike wonder, Burroughs urges us to be brave and adult, to confront the chaos. He is cruel to be kind, affording his readers a respect that more accessible and condescending writers deny. When we forgo the juvenile desire to have heroes and villains, we might see what’s really happening more clearly. "The title means exactly what the words say," Burroughs said of Naked Lunch, "a frozen moment when everyone sees what is on the end of every fork." There are no lessons, solutions, journeys or self-help he suggests and those offering such things are snake-oil salesmen, charlatans, hustlers, dealers in short, including perhaps Burroughs himself. Yet once you know how the trick works, you’re less likely to be fooled again.

William S. Burroughs was a high modernist and a writer of complete trash; the two are by no means mutually exclusive. He was a genius and a bullshit artist. If his books prove anything, it’s that profundity and inanity can skip along merrily arm in arm. Sometimes his work was heavyweight, sometimes dumb. To borrow a Freudian analogy, sometimes a cigar really is just a cigar and sometimes a man who taught his asshole to talk really is just a man who taught his asshole how to talk (what it’s saying and why is a different story). The paradox of the freest writer being a lifelong junky is really no paradox at all. As a user and pedlar, he understood the mechanics of how it all worked and kindly pointed it out to us, even as he was picking our pockets. He was a stiff morose patrician figure in a suit (so much so his friend Herbert Huncke initially took him for an undercover agent) with books and a history full of debauchery and depravity. If there seems a contradiction there, it’s in the eye of the beholder. What makes Burroughs’ work seem prophetic is that he was perceptive enough to see that people don’t change, the secret to all successful prophecies. We’re still continually re-enacting Greek myths on a daily basis and always will. Psychosis may mirror the zeitgeist (whether it’s paranoia of witches, Jews, communists, drug fiends, Islamists or whoever next) but its essential character doesn’t alter. The bugs and the feds are always with us and there’s only so much one man can do, calling door to door with an extermination kit.

Perhaps that toad fashion will tire of Burroughs and the revisionists will come along. He’ll be called a degenerate, a misogynist, a phoney and a hack, as if being any of these things could exclude him from also being a great writer. His more esoteric interests will be taken at face value and ridiculed, whether his claim that language is an alien virus, the future can leak out from cut-ups, there are no such things as accidents or dying mobsters are capable of glossolalia. "In my writing" he claimed at the 1962 International Writers’ Conference in Edinburgh, "I am acting as a map maker, an explorer of psychic areas, a cosmonaut of inner space, and I see no point in exploring areas that have already been thoroughly surveyed." There are more interesting things than reason, whether they are true or not is an issue only for pedants. Terra Incognita is, after all, a fictional place and there is a poetry and freedom in exploring it, which is the essence of Burroughs’ work and where it might lead us. "Most of the trouble in the world has been caused by folks who can’t mind their own business" he reminds us in The Adding Machine, "because they have no business of their own to mind, any more than a smallpox virus has. "Yet another world is possible. "Drunks slept right on the sidewalks of the main drag" he wrote in the introduction to Queer, "and no cops bothered them. It seemed to me that everyone in Mexico had mastered the art of minding his own business. If a man wanted to wear a monocle or carry a cane, he did not hesitate to do it, and no one gave him a second glance. Boys and young men walked down the street arm in arm and no one paid them any mind. It wasn’t that people didn’t care what others thought; it simply would not occur to a Mexican to expect criticism from a stranger, nor to criticize the behaviour of others." The utopia of being left the fuck alone might be the only utopia we deserve.