So, I could tell you secondhand stories about Manchester, the Hacienda, failed attempts to get Brian Eno to produce, more besides. But… you might have heard too many of those already. Or you can read them elsewhere, or see the films or documentaries or more. You want New Order, you got it. You want Madchester, you got it. Heck, stepping back a bit, I already talked about Power, Corruption And Lies in detail here the other year. So for now – and openly reworking/reusing some thoughts I’ve had from past discussions of and about this album and time – let’s talk Los Angeles.

It would have been almost exactly this time of year, 30 years ago. I was a freshman at UCLA, had befriended a slew of people on my dorm floor, hadn’t yet started at the radio station, feeling my way through classes, still a bit self-isolated. But I had discovered plenty of great record stores down in Westwood Village, both chain and independent, and a lot of the time I spent Friday nights down there scrounging a bit. Anyway, I was coming back from that and was just in front of my dorm, Sproul Hall.

On the way out were a group of guys I didn’t recognise offhand, probably from another floor of the hall. My quick impression wasn’t much, but they were all fairly crisply dressed, young and out on the town circa 1989, LA style. Asian American in background from what I remember, maybe a bunch of dudes who had already known each other from high school – pretty common at UCLA – or just friends from that year. We didn’t exchange more than a glance, they were all in conversation with each other or just walking along. But I vividly remember one speak/singing as I passed:

"You’re much toooooo young."

I puzzled a bit on that on my way up to my room. Wasn’t it a line from a Spinal Tap song? Then somewhere I went "Wait, DUH." I had only been hearing it for a few weeks now, but that was the first – and so far, only – time I ever heard ‘Fine Time’ completely out in the wild, divorced from any direct musical context. It was one of those weird shocks of recognition, but it made sense that they would be randomly encountered like that, somewhere in LA. New Order weren’t just New Order when it came to Los Angeles. They were NEW ORDER, and they were English and remote, and they were distant gods. But they were gods.

A little context might not hurt – when it came to so many of us in Southern California growing up in the 1980s, there were two stations: KROQ in LA, 91X in Tijuana, serving San Diego but powerful enough, due to being cross border, to be heard a good way up the coast. Well scrubbed, safely quirky perhaps, definitely as cryptoracist as anything else out there in the city – the audience wasn’t lilywhite, but the playlist denizens mostly were – but open enough to go in whole hog on ‘alternative’ throughout that decade, creating an alternative canon in much the same way that so many stations had codified ‘classic rock’ the previous decade. But they were already calcified and dull, and something like KROQ and something like 91X made you feel hip! young! alive! – the usual selling points, however shifting the contexts. It wasn’t KDAY, playing hip hop and predicting the future, and it wasn’t KNAC, high on hair metal but about to crash big time.

Instead it was the home of, incubator for, breakout vectors aligned with all sorts of bands, whether bubbling up through college radio’s own matrix or deemed worthy by Rodney Bingenheimer or who knows what else. And it had settled into its own pattern by the end of the eighties, had its own bands that had broken out bigger. And for those with a particular Anglophilic bent, there was a bit of a holy quartet, you could say, when it came to acts from the UK. Sure, U2 were bigger than all of them by that point, but they were Irish and into their own universe. Instead, four English bands, all of whom were on Warner Bros. affiliated or distributed labels and always seemed to have something new out and all of whom often had obsessed fans. The Smiths (now broken up but Morrissey had kept a lot of that audience and was about to expand it), The Cure, Depeche Mode and New Order – all of whom were all pals and lived in a house together and loved us all. Surely?

Of course, nothing further from the truth, but distance flattened distinction, and what would have been huge gulfs in experience and expectation and upbringing was only the narcissism of small differences to those of us looking at sunsets towards the ocean and choking on the smog. I wasn’t anywhere near a total nerd about such things yet, so labels like Factory and Rough Trade and Mute and Fiction weren’t as important as Sire and Qwest and Elektra, at least, to a degree. But at the same time, there certainly wasn’t uniformity in fandom either – I ended up fairly well obsessed with all four acts and so did a lot of other folks, but you’d have people raging about Morrissey’s voice, or noting disdain for anything with electronics in the arrangements, or feeling squashed by Depeche’s near total dominance above all else, the most ‘rock’ of the bands in a get-the-crowd-going stadium sense and well transitioned towards that role they’ve since more or less maintained.

And in fragmentation further distinction – if you thought of it all as elegant mood music or avoided it as miserable mope music, time and reflection pulled out further clarities and distinctions. Depeche were the rock stars as noted, Morrissey the self-willed icon, dropping references and waspishness in equal measure, The Cure losing themselves in themselves, Robert Smith’s hair the real forest. And… New Order? What WAS New Order? Who were they? By the time Technique emerged, I knew something of who they were, their history, had made the Joy Division connection, had a sense of what more was happening…but I still didn’t know, except they sounded most like what I wanted to be at the time, engaged and immediate and danceable and known and quietly sitting in the corner, all at once. Substance had already primed the hell out of me as a relatively new fan, and still feels like a massive achievement, a summary of intent and development, a new peak at every step. That’s what makes Technique so great to me still, that it took all that, took new things where it was at, hotwired it and took it further. That’s a gift.

There’s a splendid unity when it comes to Technique, how it feels of a piece. This is a unity that has become, if anything, stronger with time, something the album’s brevity brings through to the full. One time in recent years I was honestly startled when I noticed that not even half an hour had passed by the start of the next to last song ‘Vanishing Point’, a fact which I don’t think I had ever noticed about the album before. Following the eras of CD bloat and constant complaints about "only the hits being good" (then again, when wasn’t this always the case?), the briskness is something which stands out all the more – but even at the time it had to be an album notable for its relentless focus.

It’s hard to say that there’s anything extraneous on the album as a result – about the only thing I can actually think of that is is intentionally so, that cough and drone at the start of ‘Love Less’, a "mistake" or fillip that calls attention to itself by being there. Otherwise, the album is rigorously, almost maniacally precise, and though the comparison is not exact it calls to mind the particular precision of so much 21st Century pop, where the beats and space and delivery are all so tightly wound to achieve an often brilliant perfection. The ‘rock’ songs do not sprawl, there is no sloppiness, the ‘solos’ – think of the break on ‘All the Way’ – fit tightly within the songs, everything is a specific piece to the puzzle. The "dance" songs similarly seem to draw on everything they had done before and increase the impact to a slippery, endless shifting that is so fantastically and frenetically effortless.

This applies to ‘Round And Round’ in particular. After the stop-start-shift of ‘Fine Time’ – itself a razor-sharp exercise in element interacting with element and then spinning off from it at a right angle – this is even more insanely spot on. Listen to the difference in rhythms between verses and choruses, how Bernard Sumner has a ridiculously good ‘anti-flow’ flow (and even a call and response with himself at one point, all the more striking for being the sole moment like it – if it wasn’t there it might never have been missed, now that it is there it can’t be ignored), and how nothing stops – everything is pure fluidity at high speed. Compared to, say, the slow burn build of the extended ‘The Perfect Kiss’ or the triumphalist progression of ‘True Faith’, this is spiralling choreography that gets more involved as it goes until it smashes into echo and dies.

The division between ‘rock’ and ‘dance’ is ultimately artificial though, thus the quotes. The fluidity of this album, how it does feel of a piece, lies in how easy the whole idea between switching from, say, live to synth drums and back again is, how sometimes synths are more prominent and sometimes the guitars are and sometimes it’s all a specific balance and then it changes again. It’s so ridiculously unforced.

Also, this album is so beautifully bright. It is not without darker moments, the unnerving sense of threat and desperate clawing back in ‘Guilty Partner’ led specifically by Peter Hook’s bass, but something about it calls to mind the description, however inaccurate, I read once about eighties pop being an incarnation of the reflection of CD lasers bouncing off glittering piles of cocaine. The high synth melody on the second verse of ‘Round And Round’, Sumner’s ear for lovely acoustic guitars, the sweet rising/falling electronic chime on ‘Vanishing Point’ and much more. Combine that with the sense granted by the album’s precision and one can imagine this as a high-flying instance of collage, like the album was never written and conceived as a series of songs in a ‘classic’ sense, however you wish to define classic. And then of course there’s ‘Run’, their "John Denver song" – except John Denver never made so perfectly on-point melancholy as that part where it all strips back to synth string and drums and then Steven Morris quickly switches to a louder but just as steady beat.

As I mentioned earlier, I was making friends at that point in freshman year but I still felt a little self-isolated. It seemed like others around me were going but I almost didn’t know who to ask. So that meant if I was going to get to see New Order in concert a little later that year, with Throwing Muses as their openers, touring for Hunkpapa, well, I’d have to take a bus.

Looking back over all these years of slow accumulation of figuring out public transportation, to the point where I’m not only utterly comfortable with it but can’t figure out why more people don’t take advantage of it, I have to keep in mind the still pretty insular, kind of unsure person I was having to take what seemed to me like a big step. It wasn’t like I could call up the Internet to figure out the routes or anything. So with whatever resources I called on I determined that there were two lines I would need to take there and two back, and that they seemed to run late enough.

Getting to the show is all something of a blur, I just know I did, and this time around I was on the floor of what was then called the Universal Amphitheatre, looking more or less directly at the stage. I ended up chatting a bit with the people sitting next to me — I think I was right on the aisle, which I remember thinking was convenient for getting out quickly, since I knew I’d have to make the proper connections back and I wasn’t into the idea of being stranded… somewhere, someplace.

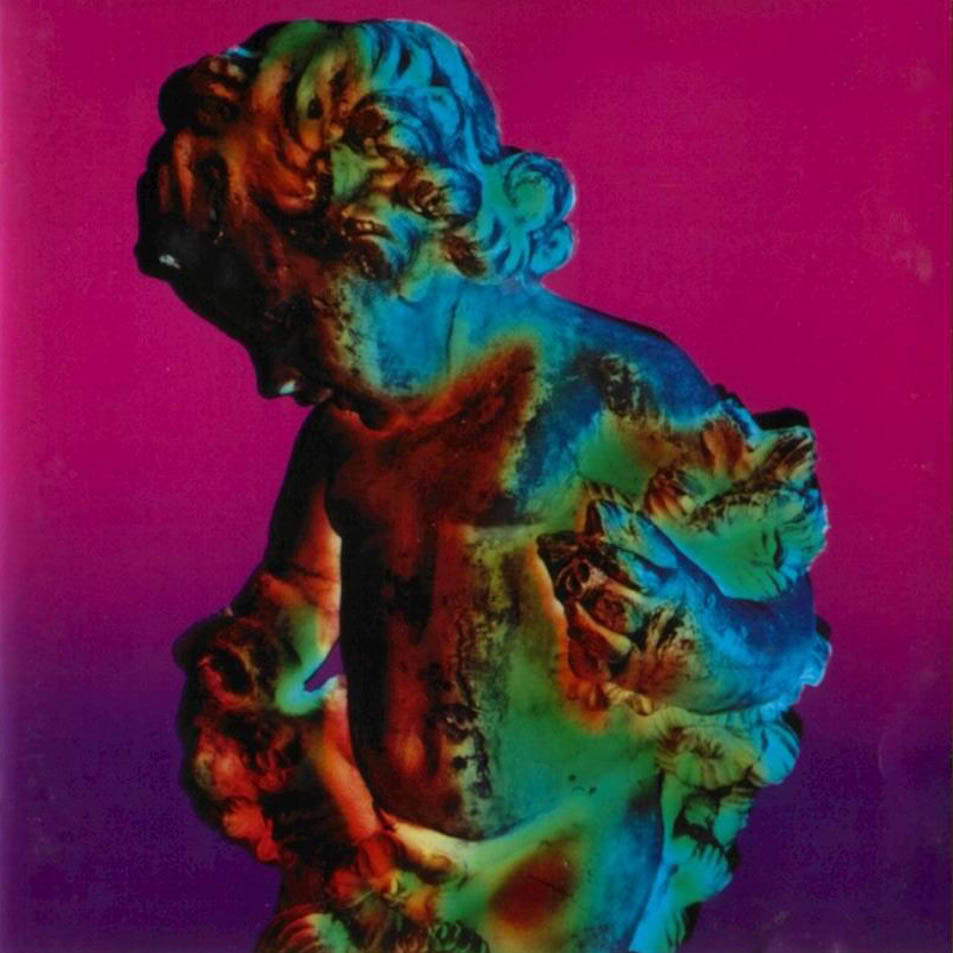

The show is mostly colours in my mind, perhaps influenced by that amazing cover for Technique, perhaps simply a sense of how the songs should be (I can’t say I have synesthesia but it would be wondrous if so). Gillian Gilbert had a purple shirt or blouse on, I recall — and I remember being surprised when they started up that she was on guitar, that in fact they were ripping into Technique‘s closing song ‘Dream Attack’ in a take that lingered in my memory for years as a rough, feedback-heavy blast, quite unlike the much more measured version on the album aside from that spindly guitar line, here given a much more prominent spot. Some very snobby (or snotty?) part of me was perversely amused and wondering how many people realised the band had ultimately started as a punk act – me, who had only learned about all that just one year earlier at most. As if everyone there had to know something like ‘Warsaw’ or the earlier demos, as if everyone had to care, as if it really mattered — still, not surprising I thought that way.

‘Temptation’ is what really still feels immediate and there from that show, the way the crowd reacted to it, the dancing, the singing along — everything really connected there to something bigger than oneself. If there’s a key vision, a stereotype, of New Order as the awkward voice amidst the slickness and the crowd while trying to be part of it as well, and how this tension plays out constantly, then perhaps I romantically thought of myself as the stereotype of the stereotype, if not in those terms, alone in a huge crowd. But I don’t remember feeling ‘alone’ then in that sense, I was just really, really loving this performance by this band I’d come to adore, the way the lights changed appropriately as Bernard sang “Oh you’ve got green eyes” and more.

I remember the encore, then I remember later asking the bus driver as I got on to see if he could announce the intersection I needed to get off at to make my connection, which he did. I remember sitting at a bus stop in a bright enough light, looking around whatever intersection with Sunset in the Hollywood area it was, probably wide-eyed, feeling a touch nervous. Sure I was sheltered, I’ve never denied that, after all. But it was definitely more than that, a sense of being out of a very specific comfort zone — at the same time, again, I can’t overdramatise it, but then again, I was alone and it was late at night, so hey. And I made the connection and got back to my dorm room and life continued on. Though I sure hope I didn’t have an early class the next morning, I would have been a wreck… actually, was that the quarter I took four classes? Including the one on Russian science fiction? Maybe?

Many years later I tracked down a good recording of the show and gave it a relisten. It turned out ‘Dream Attack’ live, that night at least, wasn’t all that much different from the album version. Was it the mix, was it the recording, or was it just me?