"Jungle’s back? Ha ha ha. Back from where? Mate… it never went anywhere. It’s always been here."

On a cold afternoon in November, the last of autumn’s heat is leaching straight upwards into the darkening blue sky, and within seconds of the sun disappearing behind London shopping centre, it’s fucking freezing. I duck inside a small Burger King franchise and after buying a milkshake slip behind a greasy and yellowing plastic and formica table to wait for Imaginary Forces, an electronic music producer and drum & bass/hardcore DJ, to show up. When he arrives, dressed head to foot in black clobber, the large, bright orange Sainsbury’s bag for life which he is lugging looks incongruous. It’s clearly well-filled and causing his slight frame to list a few degrees to the right, but a folded coat protects its actual contents from view. He nods at the bag sheepishly: "You just can’t have a bunch of people turning up at a block of flats on the hour all night long carrying record bags. Management won’t stand for it. It’s one of the reasons Rude FM have been running so long. He analyses every single weakness in his set up and eliminates all of them."

Imaginary Forces has recently returned to a regular spot on the North London pirate station Rude FM after a break of 10 years. He plays between 4pm and 6pm on the last Friday of every month. And while some things are the same as they ever were – he’s still mixing a selection of classic hardcore rave, jungle and drum & bass on vinyl as well as some newer 12"s and dubplates – some things have changed. In his absence – the station has relaunched online as RudeFM.com. The management’s notorious carefulness means that unlike most of the station’s rivals – both larger and smaller – Rude hasn’t really been off the air for any length of time since the rave scene broke in 1992 and they went into the illegal broadcasting game. But even this enviable track record hasn’t stopped them from losing literally hundreds of aerials and transmitters to BERR raids (Department Of Business, Enterprise And Regulatory Reform, formerly the Department Of Trade And Industry) and the actions of rival stations. It is also the reason why the station has undergone many moves between abandoned factories, tower blocks, friends’ kitchens, attics above shops and warehouses. And even then, their impressive success at staying on air hasn’t stopped them from, eventually, moving with the times and broadcasting online.

After a recent spate of features in the national media on the so-called return of jungle and a number of fast, breakbeat-informed releases by arriviste DJs and trend-chasing house producers, I wanted to take a look at the actual, still existent jungle/drum & bass underground. After all, we’re in the weird position now that battle recreation style revivalists and surface-skimming trend hoppers don’t even seem to be willing to let the original scenes run out of steam before jacking the most obvious signifiers and production techniques from them.

The station management is coming over to meet me and suss me out before letting me visit his current studio. Even though he’s now broadcasting via the web, there are numerous reasons why he can’t suddenly go "Ta da!" and let his neighbours know that behind his front door and partition walls are thick layers of sound insulation, massive air conditioning units to deal with the intense heat created in the tiny studio, Technics DL-1200s, Pioneer CDJs, a mixer, a powerful PC, a microphone, a wall mounted screen showing real time listener stats and a (now decommissioned) transmitter.

Old habits die hard, it seems.

"Don’t take it personally if he doesn’t like you and says it’s off", says IF. "The radio station comes before everything else."

While we are waiting, the DJ tells me about his first ever slot on Rude, back in 1998 when he had just turned 19. To many of his mates the slot he was offered was an unenviable graveyard shift, but for him it was a golden opportunity: "It was six ’til eight every Sunday morning. It was a fucking nightmare slot, but I was like, ‘This is my chance.’ I thought he was testing me to see if I could hack it so I gave it my best shot to prove that I was really into it. At the time they were in a tower block that was due to be demolished, and as it happened my mate lived above a pub up the road from there. Every Saturday night I’d go up to my mate’s pub and have a few drinks. He pretty much had the top floor to himself, so we’d go up there, do a load of beans, mix all night, and as everyone was crashing and coming down, I’d walk up the road and do my spot… and it was exactly how I wanted pirate radio to be.

"You had to sneak into the block. At least half of the residents had been moved out because it was due to be demolished. Because of this there were local gangs of kids always hanging round, so they had a security guard on the ground floor. You had to turn up there with your bag hidden and sneak in when he wasn’t looking, jump in the lift and then get out either the floor above or the floor below and walk to the level via the stairs. You’d stand out on the stairwell, text the studio and wait listening for their door to open. When you heard it, you’d go through the doors and into the flat. You had to be really discreet, because there wasn’t supposed to be anyone living there.

"During winter it would still be really dark, but you could see the red tail lights from the cars on the motorway out of the window, and I knew my mates up the road would be listening while they crashed and burned. It was very early, but it was also the time when everyone was coming out of the rave and driving home, or they were just coming in and having a spliff, listening in to your show and texting in for shout outs for their mates. At that time it was golden. I just fucking loved it. I was in my element."

Management texts eventually to say he’s in the car park outside. He is smartly dressed and drives an unprepossessing family motor, and even though he has a slightly geezerish Cockney patter, literally nothing about him says pirate radio or raves – which I guess is the point. We drive round for an hour chatting and bond relatively quickly over insomnia, workaholism and the joys of valium. He doesn’t say that I’ve passed his entry test, but without any warning he pulls over and says: "Right. You two get out here and start walking over to the studio – he knows where it is. I’ll text you when you’re right to come up."

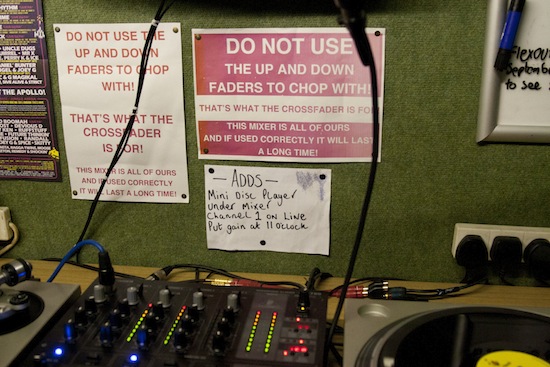

It’s nearly dark when we get to the housing estate, and we only have to loiter for about two minutes before we walk several storeys up the stairwell (he prefers ‘visitors’ to not use the lifts). The studio is essentially a room within a room, and all the walls, the floor and the ceiling are a couple of feet thick with insulation. The only decorations are a couple of vintage Amsterdam rave posters, signs reminding DJs not to answer the front door when there is music playing, and stern reminders about misuse of faders. We start unwrapping layers as soon as we get in – it is swelteringly hot. I can see why I was told to bring a bottle of water with me.

Imaginary Forces cues up a couple of dubplates he had cut recently and waits for a pre-recorded message about a Moondance Rave to finish. One of the big misconceptions about pirate radio two decades ago was that it was rolling in cash – while bigger stations such as Weekend Rush and Kool FM held regular raves and ran paying adverts, probably no one (or hardly anyone) got rich by running or DJing at a pirate alone. This notion may have come from sensationalist news reports running in the mid-90s which claimed that illegal stations got their money by playing adverts for drug dealers. Management grins when I bring this up and says: "I don’t know much about drug dealers, but I’m pretty sure that the last thing they’d want to do is to take out an advert on the radio and say, ‘Here’s my phone number – give me a bell if you want some ecstasy.’ Just think about it – it doesn’t make any sense."

Rude doesn’t really run many ads, but he will play the odd bit of promo for mates throwing raves and parties. This, he says, happens for the price of "a drink" and is certainly not enough to cover the bills. The station is maintained out of his and all of the DJs’ pockets. Everyone who has a regular slot pays sub money, which goes into maintenance and paying bills.

Imaginary Forces starts playing a track that is unmistakably jungle, but quite sparse and brittle sounding – it begins unfolding slowly in an icy manner – it’s punchy but lacking in knuckleheaded machismo. He starts checking the studio’s mobile and PC for messages from listeners. He picks up the mic and introduces himself: "This is Imaginary Forces with you ’til Eight. Big up the Menk in the studio tonight. A shout out to Kodiak listening at home…"

Management ushers me into a space no bigger than a broom cupboard for a chat in the relative quiet and relative cool. He explains that when he was in school he was a fan of house, electro, rap and hip hop, but it was the advent of acid house hitting the UK which really altered the course of his life: "It was because of my passion for the rave scene that I moved to London in 1991 when I was 16. I started listening to a couple of pirate stations that I could pick up. Weekend Rush, Kool and Pulse FM were the main three that were around back then doing hardcore and early jungle. Eruption as well. It just used to fascinate me – I started listening at first because of the music, but then there was another side to it that really got my attention. ‘How do they make these broadcasts? What equipment do they use? How does it all work?’ I realised that I wanted to do my own station.

"One day I bumped into a friend of a friend and he mentioned about radio and how he used to run a little station. Well, as soon as he said that I was on the guy. I got chatting to him and we became good mates in the end, and eventually we became partners. I approached him with the idea, ‘How do you feel about starting up a station?’ He had money. I didn’t have any money but I had certain skills to offer, as in doing quite a big workload to keep the station running if he was willing to put in and fund it. He said yeah, and so I started learning about it. My friend had done it all before, so he taught me how to put up aerials on tower block roofs."

In the early 90s the set up was pretty basic: "Back then there were no CDJs, so all we needed was a pair of Technics 1200s, a mixer, a microphone, a stereo and speaker. Then on top of that you need a transmitter and the other bits and pieces that you need to get on air. We never broadcasted ‘direct’ from the studio. You’d get the odd station that would do it, but that was a silly way to operate because when the authorities would come and find you, then you would lose all of your decks and everything like that. So right from the beginning we got into ‘linking’.

"Basically we’d have the studio in one location which could be anything from one mile away to eight miles away. So we’d have an output site – normally a council tower block, because there were lots of them around. You need a high point to transmit from, and the higher up you go the further your signal can reach. You have a smaller transmitter in your studio called a link box, not on FM but using other frequencies, and that would send your music across to your main transmitter and then it would go out from there, and it would sort of make it a bit safer for your main studio.

"Originally when we first set up it was called Raw FM, and we were getting a team of good DJs together, but we didn’t take it that seriously. It was a bit like the rave scene – it was like a party on air all weekend long. Loads of people up there – not like how we run it now, which is very professional. We did that for about a year, and it was more of a fun thing. And then we realised that we had something a little bit special, and we thought let’s just switch off and we’re going to come back on, on a different frequency, have a bit of a tidy up, get rid of some DJs, get a few new ones and come back a bit more professional, and that was when we came back in 1992 as Rude FM."

Over the years the station has been host to some renowned names inside the scene. Dylan and Facs are two notable DJ/producers signed to Danny Breaks’ label Droppin’ Science, who came up through the Rude ranks. There was also Fracture and Neptune, who started as a DJ duo and ended up signed to Droppin’ Science, but then went on to form their own label, Astrophonica, with Fracture graduating to Metalheadz recently. Another Rude alumnus Dylan ended up forming his own label Freak Recordings, which became a huge deal in pushing the much harder/darker side of D&B. Other former DJs turned label founders include Break, DBR UK, Psylence, Sabre, Alix Perez and many more. The station has also seen guest shows from the likes of Klute, dBridge, Skeptical, Anile, Genotype and Phil Source, to name but a few.

That these people – even though obviously talented and forward looking folk – went on to bigger and better things was more by accident than design, as far as Management is concerned. He refuses to book circuit DJs, prides himself on always working with fresh talent, and would sooner nurture younger, harder working bedroom DJs than already established names – even though they would undoubtedly attract more listeners. At any one time Rude has 25 – 30 DJs who all pay subs toward the upkeep of the station. And it isn’t just knackered old cheesy quavers who are beating a cautious and discreet path to his front door – there are a surprising amount of younger recruits, which points to the relative health of the scene.

He laughs and says: "I was talking to our youngest DJ recently and we worked out that he would have been three years old when I first got involved in radio!"

I mention that, like other people who lived in the Home Counties twenty years ago (I lived in Hertfordshire and Essex when jungle was morphing into drum & bass), radio was my lifeline or vicarious contact with what was going on in London. It felt important because it was literally the only medium that let you know that there was life beyond the warehouse you were working in and the Britpop being played on the legal stations. "Yeah, I used to have listeners who lived out of town, they couldn’t pick us up and they used to drive to certain hills or spots where they could receive the signal and sit there for two hours doing a tape and then take it back home with them."

When asked if he knew how far Rude broadcasts could be picked up, he says: "Back in the good old days, when we could get up on spots that we can’t even get a look in on now, we would go out to Luton, South End, deep into the south, fly over west… we used to fly out to a big area."

Talk turns to the actual illegality of the FM broadcasts, the popular misconceptions surrounding them, and the skewed arguments used in the mainstream media to turn public feeling against the practise. The most ridiculous assertion – that the stations were all fronts for drug dealing operations – reveals a massive failure of the imagination on the part of the authorities (then the Department Of Trade And Industry or DTI): namely that young, low income people living in urban areas aren’t capable of expending such amounts of time and ingenuity simply in the support of culture, and that all this effort must be connected in some way to an illegal get-rich-quick scheme. And I use the word culture advisedly – hardcore, drum & bass and jungle remains one of the truest high water marks in post war British art and culture. But on top of the ridiculous bogeyman of the rave MC as FM frequency drug pusher, we had the oft conjured image of a packed jumbo jet full of screaming holiday makers flying straight into Canary Wharf because the pilot had caught an unexpected blast of ‘Original Nuttah’ in his headset.

Management, to be fair, doesn’t outright ridicule this idea. "It’s not really dangerous. I’m not saying you never get stray transmissions but there aren’t many, and when you look at the number of years pirate radio has been going for and how many people have been involved during that time period, the actual number of incidents is very low. But I won’t say that radio signals never get picked up by the aviation industry, because it has happened once or twice at Heathrow and Luton. But that’s mainly due to certain people buying dodgy transmitters that are not built right so they’re sprogging – which means they’re broadcasting on the frequency that they think they are, but they’re also generating noise on other frequencies that they’re not aware of and they’re cutting into other, legal, broadcasts. [The DTI] want the public on their side, so they bring this stuff up all the time. I know for a fact my transmitters don’t interfere. I used to have long runs of seven or eight months and not get taken down. Do you think they’d leave those transmitters up if they were interfering with commercial air traffic? They wouldn’t. They’d take them down immediately."

He seems to have much more time for the people who were tasked with shutting him down, however, and he speaks fondly of the ingenuity that they were forced to employ to stay one step ahead of the DTI. "Back in the beginning it was very basic. We just used to bodge the aerial up and go on air. We didn’t really have a sophisticated an approach. We’d go out on to a roof and gaffa tape an aerial to the structure, just tie a mast to some bracket with a bit of cable wrapped round it. The transmitter itself you’d chain it up to something. But back then there weren’t that many stations around so you could leave your rig sitting round on the floor and no other station would come and take it. It wasn’t like it is now – it’s very popular. Everyone’s doing it.

"But then over time you start to think about how these units are costing money and how you are essentially just giving them away. So you start thinking about how to hide them away a bit better. One day I came up with an idea… On the tower block roofs there used to be ventilation shafts and I had this mad idea for putting the transmitter down the shaft. I knew I’d have to fix it in place and I came up with the idea of using a car jack – just a normal one from the boot of your car not a hydraulic jack. So we started hanging transmitters off jacks and then putting the jacks down the ventilation shafts and winding them out so they’d be braced against the walls. And after a while we’d be going up to the roofs after we’d been hit and the transmitter was still there and the wires have been chopped and you’d be like, ‘Ah! That’s a bit nicer, not having to come up and buy a new transmitter.’ But then after a few months they’d work out how to get it out and then you’d have to step up again. They would often leave evidence of how they dismantled it and once you spotted that you could work out how to tackle the problem."

He is quick to admit that there was a game logic element to this need to keep switching up designs and procedures: "I’m mainly a radio engineer (by day) and I loved that challenging aspect of it. It was a bit like the rave scene in the early days. I used to love going raving because it was an illegal party but they’re both victimless crimes. I’m sneaking on to a tower block roof but I’m not stressing anyone out or giving tenants grief or causing a problem. I was always very quiet – you had to be.

"I’ve bumped into the authorities and we’ve had a chat. Sometimes a transmitter’s gone off and we’ve turned up and we’ve seen him come out with it under his arm. They know who you are. They’re not bad people and I’ve had some quite good chats with them in the past. I’ve always kept it friendly with them and respected the fact that they’re just doing their job."

He talks with pride about his longest unbroken run on the air without losing an aerial – a year – and admits that the whole process is quite habit forming: "The radio’s like a drug. You want to give it up but it keeps calling you back. You do come close though. You think ‘What am I doing this for?’ It pushes you to your limits and the stress… But it’s a hard thing to pull away from. I know plenty of people who gave up but they always come running back to it and start up again."

He adds: "But there’s also a need for it. There are no legal stations where you can hear what we play. Even the legal drum & bass stations that are round or have been round, we always come at it from a different angle with our music policy. We’re playing the stuff that the other drum & bass stations weren’t playing. And that’s why I keep on doing what I’m doing to this day."

Management says that if anyone is thinking of running a pirate station they should be aware that it’s a 24/7 kind of lifestyle that by necessity trumps everything else in your life. "It plays havoc with your romantic life", he sighs. "It used to be that I’d never have a girlfriend for long. They’d love it at first, the idea of the radio station but they’d grow to resent it because it takes up all of my time. And unfortunately I have to put the radio first. It may sound selfish but when it’s off air it needs to go back on immediately. My partner now is a DJ on the station herself; that was a good connection for me to make because she understands what is involved."

It’s getting on for 6pm and Imaginary Forces is playing his last 12" while the next DJ up, Sweet Pea is flipping through her records and CDs in preparation.

When he’s finished and all packed up, we wait til we’re sure the coast is clear, kill the studio speakers, slip out onto the landing and then down the freezing stairwell and out into the night. As we walk back up to the main road, Imaginary Forces, who has been DJing since his family moved to London when he was 13 tells me about his first exposure: "The first pirate station I got into was Unity on 88.4 based out in Romford or thereabouts. It was my sister’s station and they had really great DJs like Scooby. They’d always have the mic open so you’d always hear them laughing and joking and there was this vibe… this atmosphere… I had this idea of what radio was like but it was a very juvenile idea of what it was – naturally as I was only 13 but I knew it sounded exciting."

Of course, being a school boy, it was his only access to the music because he was too young to even attend raves. This narrow window of access fired up his youthful imagination: "I had no idea what raves were actually like. I remember I had a tape of a Mickey Finn set at Telepathy and I would try and work out what they would be like… latterly when I actually went to a rave, it was totally different to how I’d imagined but when I was a kid… radio was my lifeline."

One thing that people often don’t reference is the big gulf between pirate radio and raves. Pirate radio DJs tend to take more chances and make more radical selections: "Being primarily a pirate DJ has completely influenced the kind of DJ I am and the sort of music I make myself. Pirate DJs always took more risks and played tunes you wouldn’t hear in the raves or clubs. I think the radio always showed a much more diverse spectrum of what jungle was and what it could be."

IF was still a bedroom DJ when he turned 15 and his family moved to Hainault where he hooked up with people who had slots on a local pirate called Force. He sent them a demo in 1998 when he was 17 and got called in. And then it wasn’t long before his try out on Rude, 16 years ago, when he was still mixing under the youthful moniker, Kudos.

Imaginary Forces on Rude FM – 27/09/2013 by The Quietus on Mixcloud

He left Rude in 2003 but went back in 2013 due to a love for jungle and hardcore: "My own music has taken a very different path but those formative years being a pirate DJ were really important to me – for how I make music, how I look at myself and how I present myself. It gave me this real, ‘Fuck you, I’m going to do it’ attitude. Recently I’d just got back into buying D&B music and drifted back into mixing it at home. Then it was a case of, ‘What’s the point in just doing it at home?’ And then I started hearing some more new D&B coming through which really wowed me – like really amazed me. It was the best stuff I’d heard in ten years. A lot of stuff on Exit Records, which is dBridge’s label and on Samurai is great. There is FIS who has a very singular voice and he is doing stuff that no one would have played in a set or put out on a D&B label ten years ago. And I was always a fan of what Loxy and Ink were doing.

"When I first started following Loxy, his music was really heavy, breakbeat stuff but it’s developed into this music which is really sparse. They’ve taken a lot of the breakbeats out – they use smatterings of them here and there – which has really opened up the space. You’ve got to bear in mind that when I started the tempos were much slower about 130 to 150bpm so you had more space for everything to breathe. By the time it was 2000, we were up to 175, 180 bpm and it was just flat. Everything was squashed together. But by taking the first and third snare out it leaves loads more room for it to breathe. The music becomes much more experimental again.

"And it was experimental music. If I drag out an old record like 4 Horsemen Of The Apocalypse and on the b-side to that there’s a Michael Nyman sample from one of his Peter Greenway soundtracks. That’s a really mad thing to crop up in the middle of a really dark jungle tune. And these days I think people are taking those risks again. Obviously it’s a lot slicker now and not as rough and ready as it used to be but they are the same kind of risks and I find that exciting."

It’s hard to pin down exactly why D&B has become such an evergreen sound. Even though there is more to the sound than the Amen break (and as Imaginary Forces points out – for some producers, there really isn’t anything outside of the Amen break) it still doesn’t explain its longevity: "I think, when you look at the evolution of it from acid house to hardcore to D&B every month it would change, it would mutate into something else. And then around 2000 it kind of stagnated – there was a blueprint, a template to which you could write tunes to and everyone started sticking to that formula. But D&B is a trend based music which is its downfall and its saving grace. So every few months someone would come up with something that nobody had done before and then everyone would copy that for a while and that would become the new trend until that stagnated and then someone else would come up with something new and people would copy that. So in a way it constantly reinvents itself. If I played you a track from 1990 and then played you a track from last month on Samurai, they’re a world apart but then if you trace them back there are also obvious aesthetic connections.

While we’re waiting for a bus, I ask him about the 2013/2014 jungle revival, which has been mentioned everywhere from fashion mags to The Daily Telegraph: "This whole wave seems to be old house music producers who have suddenly gone, ‘Oh, we’ll just throw in a few breakbeats.’ And for me it’s an insult. And worse, it’s a throwback. Four Tet just recently called a tune ‘Kool FM’ and that’s just crass. It really bugged me. All he did was take a crappy loop. That’s it. There was nothing in that tune at all. For me there’s no substance there. It’s just vicarious cool.

"If you look at Mumdance & Logos – those guys who pushed that kind of dubstep beat forwards by using loads of old jungle breaks and D&B basslines – that’s cool because they’re moving things forwards. It’s not the same as some old house producer going, ‘Well I’ve been making house for years but I’m bored of that now so I’m just going to throw some breakbeats in.’ It’s not necessarily a bad thing on its own that these guys are pillaging a heritage that doesn’t belong to them but they are not putting anything back into it. They’re taking from a community that still exists.

"They swoop in and say, ‘Oh, this is cool now, let’s do this for a bit.’ And they do this music and get bookings in these white boy, hipster venues. Those venues and that crowd are like, ‘Well I like this music but this is safe. I like this music and this way there is less chance we’ll have to rub shoulders with any chavs. It’s really beige. There’s no energy in it. Sure when I was young and I went to Telepathy there was that feeling that if I mixed it up with the wrong person I might get stabbed but at the same time I was having the time of my life listening to the most amazing sounds. These new guys are like the Dire Straits of jungle revival. It’s awful.

"When it comes to big clubs like Fabric – they’re all over this shit. Yeah, sure they’ll book the big names like Randall, Grooverider or Goldie but why not also tune into some of the heads who have been doing this for years, someone who is really fucking good and on the cutting edge of D&B instead of someone doing a throwback revival thing?"

I bid goodnight to Imaginary Forces and eventually when I get back home I look up Four Tet’s ‘Kool FM’ single and Beautiful Rewind album online and am quite dismayed to see what Boomkat have written about his foray into drum & bass:

<a href: "http://boomkat.com/downloads/824940-four-tet-beautiful-rewind" target="out">Beautiful Rewind: "Kieran Hebden… is appropriating and reworking the sounds’ signifiers to alter their original purpose, dosing their mania with a wider appeal for those who want to rave but without all the nasty bits…"

‘Kool FM’: "Four Tet dials into Kool FM’s jungle heritage with the first whiff of his upcoming ‘Beautiful Rewind’ album. Amen appropriation is all the rage right now and Kieran Hebden’s having his slice of the fun…"

I mean, you don’t need to be Umberto Eco to parse the sense out of this. And I don’t blame Boomkat for describing this exactly as it is. I believe in calling a spade a spade and this is what they’re doing.

I close down the window and open up RudeFM.com. They’re still transmitting rebel bass live and direct from the underground: exhilarating, awesome, rough neck, innovative and future facing; nasty bits and all.

You can catch Imaginary Forces between four and six on the last Friday of every month. Click here for the rest of RudeFM.com’s timetable