Once, before a concert, Laraaji contemplated a triangle. He spent “about half an hour, concentrating on the geometric form of a triangle,” before finally “letting go” and taking the stage to perform.

“After the concert,” he told me, “one person came up to me and mentioned that they kept getting a vision of triangles during my concert.”

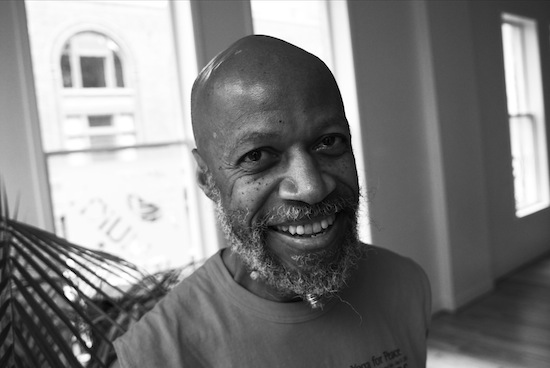

The zither and autoharp virtuoso, laughter therapist, and new age music pioneer Laraaji was born Edward Larry Gordon in Philadelphia in 1943 – or rather, as he says in the extensive sleeve notes to his new album, “the body was”. Celestial Music collects material from throughout Laraaji’s recording career; from the thrumming, scintillating minimalism of 1978’s ‘All Pervading’ to the heavy drones and skipping rhythms of his 2011 collaboration with Blues Control, ‘Astral Jam’. It’s one of three new Laraaji releases on All Saints Music. On the phone from LA, where he is in the midst of a US tour, he told me about his concept of ‘architectonal music’.

“I’m not sure of the way it’s used in the dictionary,” he qualifies, but for Laraaji the ‘architectonal’ is all about the power of sound to shape “the architecture of the imagination. Music can suggest the direction for the emotions or the imagination to go,” he continues, “whether in the form of geometrical forms or free open landscapes or vistas. That’s one of the understandings in consciousness music or healing music – that sound and music is a carrier wave of our intention.”

Growing up in North-West Philadelphia, Laraaji remembers his mother singing “television soap box themes or humming church music around the house”. He grew up steeped in the music of his

local Baptist Church. After studying composition at Howard University in Washington D.C. he eschewed the concert hall for the more immediate hit of solo street performance.

Writing for orchestra, he told me, “sounded like a lot of waiting between the conception of the composition and actually having it performed, and also putting a lot of trust in the hands of a

conductor and orchestra members.” As a solo act, “I can come up with the composition on monday and I can perform it on friday. There’s a tighter transmission of the intention into the actual

listening experience.”

These days Laraaji tours with an iPad Mini alongside his zither and his kalimba, so he can add “little seasonings of flute, oboe, or harp, and get an orchestra sound without hiring musicians”. He

has no truck with “purists” who poo-poo the infidelities of digital sound. “A musician,” he insists, “can take all that into consideration and use it as the content.” He will admit, however, that his early “vision” as a composer was “to represent the sound of a large cosmic orchestra” and from time to time he still hankers after sinfonia. Either that, or to work on a Broadway musical.

It was while performing on the sidewalks of New York that he met Brian Eno, in 1979. Since the early 70s, Laraaji had been “investigating different spiritual paths”, practising a cocktail of disciplines from yoga and meditation to tai chi. Sensing the “inner quietude” being transmitted through his music, yoga teachers began inviting him to perform during their classes to set what he calls “a meditative state” before they began teaching. Later, he would record himself playing and dub his own cassettes to sell to teachers for when he couldn’t make it in person. But it was the encounter with Eno that brought Laraaji’s music “to the global level of distribution”.

It happened like this: Laraaji was sitting in the lotus position on a little blanket in Washington Square Park, tapping out a delicate tintinnabulation on a zither plugged into a little practise amp.

His eyes were closed. The sounds wafted through the park and out onto the street, echoing against the apartment blocks and down side alleys. Eno was taking a walk in the park with Bill Laswell and, upon hearing Laraaji’s playing, drafted a quick note and dropped it in his case. At the end of the night, the busker found a sheet torn out of a note book amongst the night’s takings.

“Dear Sir,” it began, “please pardon this scraggly piece of paper, but I wonder if you would consider participating in a recording project I’m launching.”

That project was the Ambient quartet of albums on Editions E.G., of which Laraaji’s Day Of Radiance would comprise the third part. Recorded mostly with the zither and hammered dulcimer, the first side of the record consists of three tracks, each called ‘The Dance’ and numbered one to three. The name derives from an unusual aspect of their process of composition. “I used a visualisation,” Laraaji told me. “I visualised imaginary folk dances.”

Eno produced the record and applied some discrete electronic treatments to the performances. Laraaji remembers his producer as “very respectful, giving me a lot of space in the studio but at the same time he was courageous enough to suggest ideas that would take me out of any boxes that I was in. I’m using some of those suggestions even today”. And they’re still in touch. Eno paid Laraaji a visit in the spring while he was in the States for the Red Bull Music Academy and Laraaji returned the visit while in the UK in the summer. “The guy is sharp,” he tells me. “He has his brain wrapped around many subjects.”

If he first came to international attention as a purveyor of ‘ambient’ music, he would soon become indelibly associated with another generic tag that was poised to take over vast swathes of American airspace as the 80s progressed: New Age. The key difference, for Laraaji, is that while ambient may be “more poetic than new age”, the former does not always have to be pretty-sounding – just as long as it “supports the idea of being an immersive, total atmosphere.” New age, on the contrary, is always beautiful music. Easy on the ears. Calming. Whether that’s using electronics, or acoustic instruments or, as Laraaji tells me, “you might even use music that’s recorded from the stars”.

Laraaji is very comfortable with the tag. New Age, he says, “gave a name to what I was already feeling. It was a new age for me because the inner spiritual experiences and the epiphanies that I

experienced in the 70s were merging through my music. To me,” he continues, “new age means now. I was very much into now-ism. Through meditation and being very present. I still am.”