Moby called Thom Yorke an old man yelling at trains the other week. Upon hearing the news, Yorke – the man who at the dawn of the 21st century loudly tossed away his guitar and embraced electronics – yanked his indie senior citizen bus pass out on twitter and proudly declared himself "A 45-year-old luddite and proud of it." No one should expect a Biggie & Tupac turf war to erupt off the back of this mild exchange, but if you’re looking for a 140 character or less summary of the year’s biggest debate in music and tech, then these two middle-aged musicians nailed it.

The debate, of course, is Spotify (now the de facto figurehead for all streaming platforms) versus musicians who’ve accused it of doing everything from not paying new artists to destroying creativity full stop. No other story has so perfectly dominated the axis between the music, technology and general press in 2013. At the centre of the ruckus lies a handful of music types, a bunch of bloggers and Spotify. The mud slinging has been fierce, and with it came a deluge of stories, erroneous statistics and opinions masquerading as hard truths. Now that we’re all essentially the media thanks to technology and social media, it’s become almost impossible for listeners to understand what impact their digital consumption actually has on the music they love. I’ve seen people on my own Facebook feed worryingly ask if they should stop streaming music, while others have turned into rabid streaming naysayers armed with bogus figures skimmed from the web during their lunch break.

The reality is simpler and also far more complicated than most of the pundits let on. For the sake of music fans, who’ve been forced to quietly sit through this like children trapped in the middle of a ferocious custody battle, here are some essential things you need to know about the great streaming battle of 2013.

Meet the Nays

Thom Yorke is the name most associated with pushing the Spotify debate into the mainstream spotlight last July, but it’s Nigel Godrich, long time Radiohead producer and member of Atoms For Peace, who was the most vocal driver of the criticisms against Spotify. His core argument is simply that the current Spotify payment structure is slanted heavily in favour of the major labels; labels who get a much larger share of the streaming rates, thanks in part to "secret deals for favourable royalty rates" and catalogues that include hugely popular artists like Katy Perry, Beyoncé and Led Zeppelin. Small labels and newer artists, he argues, have the odds stacked against them, in part because they’ll inherently have a much lower volume of streams and they’ve been given a far smaller share of the royalty pie thanks to those "secret deals". For Godrich, the main point here is that the system simply doesn’t work for catalogue AND new artists. They can’t be lumped together.

Godrich and Yorke, who also count Beck and most recently Johnny Marr among their number, are two of the most high profile critics of the streaming model. The debate really started in 2012 when Damon Krukowski of Galaxie 500 and Damon & Namoi penned this piece for Pitchfork. In it, he breaks down what Galaxie 500 earned from Pandora and Spotify plays in the first quarter of 2012. The results can’t even be described as meagre. Krukowski finishes the piece by announcing that all of Galaxie 500’s records are now available to stream freely (or buy) on the band’s Bandcamp, a platform that offers no payment for streaming.

Though Krukowski’s piece has been one of the mostly widely circulated – including by Godrich – it’s Cracker and Camper Van Beethoven frontman David Lowery who’s been the most active campaigner for artists’ digital rights. Over the past year he’s done everything from release a study of the most undesirable lyric sites – which led to the National Music Publishers Association filing take down notices with 50 sites – to arguing that Google supports piracy through Google Ads that appear on pirate sites. You could write an entire Wreath Lecture on Lowery alone, but in the streaming music debate it’s this post, where he shares his songwriter royalty statements from US streaming radio platform Pandora, that’s become another signpost for many in the anti-streaming camp.

And even with that many critics shouting from the castle walls, it was a piece published by David Byrne in The Guardian in October that blew up the streaming debate even more and brought it to the attention of people who think Yorke and Godrich are just types of ice cream. Titled The Internet Will Suck Creative Content Out of the World, Byrne’s article echoes Godrich’s claims that the streaming system is stacked against newer artists. As part of his argument, Byrne rolls out stats claiming even Daft Punk are set to only make $13,000 each from ‘Get Lucky”s 104,760,000 streams, a figure that by the time of its publication in The Guardian had already been disproven by the commenters in a post on Death & Taxes Mag. Their post initially attempted to make the same ‘Get Lucky’ claim as Byrne, before the writer realised his mistake. For the record, if you’re using the per stream royalty numbers shared in the Death & Taxes piece, Daft Punk will have made $966,947.68 for 100 million streams of ‘Get Lucky’.

Meet the Eks

Daniel Ek is the 30-year-old Swedish founder of Spotify. Even though YouTube, Pandora, Soundcloud, Rdio and Deezer, among others, are all digital streaming platforms, it’s his company that has become the lightning rod in the streaming debate. There’s been a lot of assumptions made about Spotify, but here are the basic facts you need to understand about how it operates as a business.

Spotify is a music on demand service, unlike Pandora, which is a personalised online radio service, or iTunes, which is a digital version of a bricks and mortar record store where you pay a one-time fee to own the music. A music on demand service does what it says on the tin. You want to hear a piece of music? Do a quick search for it. If Spotify has it, you can listen to it. Spotify makes its money in two ways. It offers a free version of the platform that includes ads you have to sit through. Or, you can subscribe for £10 a month to access an ad-free version that also gives you the ability to save playlists (which for many users simply means albums) on your mobile for offline listening – essentially the same thing as loading up your iPod or iPhone with music.

That’s how you or I understand and experience a streaming service like Spotify. Things begin to get complicated when you start poking around how the money Spotify pulls in gets paid back to the artist. Most people assume that when they hit play, the artist gets paid. That’s not the full story.

Spotify currently pays nearly 70% of their total earnings to rights holders and keeps the remaining 30%. It’s a pretty standard royalty breakdown in the digital space today. If you build and sell an iPhone app, for example, Apple takes 30% from every sale. The same applies to Amazon if you sell an eBook in their Kindle store.

The key word to remember in the above paragraph is rights holder. A rights holder does not automatically equal the artist. A rights holder is usually a record label or music publisher. To release their music, an artist will generally sign the recording and publishing rights over and agree to some kind of sharing of the royalties earned. The label holds the recording rights and is normally responsible for doing everything from funding and manufacturing a record, to marketing, PR and getting the music on the radio. The label will also typically work with a distributor, whose job is to get the record into stores and then takes a cut from the sales for their efforts. The music publisher holds the publishing rights, and they do things like collect royalty payments from radio.

Even after getting paid, the artist will also have costs they need to pay out from what royalties they finally receive. This normally means giving managers a cut, for example. There’s also a huge number of variables, including what can often look like an enormous amount of deductions for things like recouping recording costs and accounting for potential breakages during shipping, that affect how much money ends up in the artist’s hands. The contract terms an artist strikes with the rights holders will have a massive impact on their earnings. And while it might be easy to raise your fists in the air and shout "damn you labels-distribution-music publishers for screwing over artists", for every story you hear of a bad record company, there are many examples of good companies and people who provide a genuine service to the artist and work hard to ensure they get a fair deal.

Like a Facebook relationship status of yore, it’s complicated, and things have only become more complicated in the digital era. After all, who collects royalties from a streaming service like Spotify? Is it the distributor, who would normally have been collecting the money from album sales, or is it the publisher, who would have collected money from radio plays? And does a stream count as a sale, which normally means an artist gets a smaller cut as the label has to recoup for things like the physical manufacturing of the record? Or is it a radio-like play, where the publisher and artist normally split royalties 50/50? Beggars Group, home of Adele, Vampire Weekend and Atoms for Peace, give their artists a 50/50 split of streaming revenue because they can’t justify labelling a Spotify stream a sale. The fact that Atoms for Peace’s label gives them a generous split compared to the 10 to 15% you hear for other artists does raise some eyebrows, but more on that in a second.

In Spotify’s defence, they’ve been doing the right thing by paying out 70% of their total revenue to rights holders. Spotify’s challenge here is simply that they’ve entered an industry that’s historically operated through complicated relationships and a very, very tangled web when it comes to the money.

Some answers for the Nays

In order to get to where they are today, Spotify made various deals with labels, including of course the big labels with major catalogue artists. Though Godrich, in his attack on Spotify, labelled them "secret deals", the reality is that it’s been an open fact since at least 2009 that the big labels were all givensizeable shares in Spotify early on. They have a tangible interest in the company, and with Spotify now valued at $4 billion as of November 2013, it’s clear the labels could be set for a very big pay day if a tech giant like Google bought them out. Just so you understand how much of a drop in the bucket $4 billion is to big tech companies, Samsung spent £14 billion on marketing alone last year. The estimated total global revenue for the music industry in 2013 is £17 billion. Some argue that Spotify are simply taking the music industry for a ride in the hopes of cashing out in the near future, but there’s been no sign of this from the Spotify camp. Their focus, like Netflix, appears to be centred on becoming a media-tech giant in their own right.

Having been fairly subdued in their response to critics, Spotify finally offered up a dose of real transparency a few weeks ago with the launch of Spotify Artists. The website is designed to explain to artists how Spotify works and how its earnings are divided up among rights holders. Having looked at their revenue sharing model, the truth is that when it comes to the sharing of earnings, Godrich is right. The total amount of money generated each month by Spotify is paid out to rights holders based on how many streams they contribute to the monthly pot of streams. Which means Spotify doesn’t really pay out on a per stream basis, they divide up the pie on a monthly total. So, if you’re a label with a huge catalogue of classic artists and current superstars, you’re far more likely to get a bigger piece of the pie than the small indie label with a new underground artist, simply because your catalogue is contributing to more streams. Other factors also have an impact, including what territory the music is streamed in (artists will often have different royalty rates for different territories), and whether the listener is a free or paying user – Spotify pays rights holders a higher royalty rate for subscriber streams.

The fact is that big labels make more money because they have more popular artists. The smaller artists make less money because they’re simply not as popular. Reduced like that, it’s hard not to see something that looks an awful lot like the pre-digital status quo. Where things become harder for the indie artist as it currently stands is that, in a streaming environment like Spotify, there is no room for a DIY music economy to flourish outside of the mainstream. To participate, you have to enter into the same ring with the heavyweights.

You can light your torches and start burning your iPhones now if you like, but there’s one key point the anti-streaming brigade continually ignore when discussing the streaming music issue…

…the ring they refuse to step into is tiny.

Even with a valuation of £4 billion, Spotify is not a globally mainstream platform. The last time Spotify officially released user numbers in April 2013, it announced 24 million global users, with six million of them paying subscribers. To put that into context, 47.7 million Brits (90% of the population) listened to radio in the third quarter of 2013. Appleannounced in June that it now has 575 million active iTunes users. YouTube currently lists its monthly user numbers at one billion, with over six billion hours of video watched each month – that 2013 viewing figure is up 50% from 2012 – and it is officially the largest streaming music site in the world.

Spotify is small. But even at its current size, Spotify has paid out $1 billion to rights holders over its short lifetime, with $500 million of that in 2013 alone. What a lot of the critics complaining about streaming services keep missing is simple:

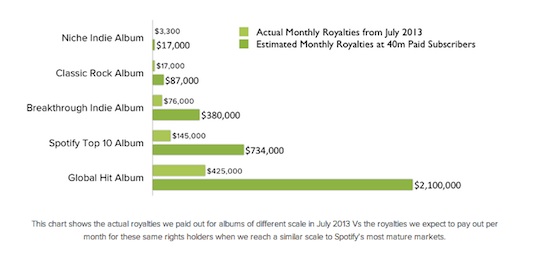

The first thing is scale. The more a platform like Spotify scales – meaning the larger it gets – the more it can pay out to rights holders. If Spotify has paid out $500 million in 2013 off the back of 24 million users with only six million of them paying subscribers (remember that Spotify pays out a higher royalty share for subscriber streams), imagine what it could pay be paying with 40, 60 or even a 100 million users. The monthly royalty pot available to all musicians becomes much, much larger.

This chart from Spotify highlights how much they paid with six million subscribers to five different types of albums in July of this year, and what they could pay out for those same albums with 40 million Spotify subscribers.

When it comes to the numbers, a lot of of what’s been recently slung around as sacrosanct data in the debate is old. The royalty numbers from Krukowski’s piece, for example, were taken from the first quarter of 2012. In that same quarter, Spotify’s official user numbers were still 10 million with three million paying subscribers. There’s a reason why long time streaming holdouts like Metallica, Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin are finally appearing on Spotify – the 2013 numbers point to them making a lot of money as legal streaming grows. The once anti-streaming Dave Stewart of the Eurthymics told The Guardian last September that if Spotify had 100 million subscribers, the Eurthymics would be making as much money as they did in their 80s prime.

But even away from how much money a handful of music dinosaurs could make off streaming, the key second issue rarely discussed is repeatability. Historically, money on music sales was made by a one time transaction. You paid for the record in a store and that was it. The only money made was at one single point. A streaming model offers something different. Every time you play your favourite artist, they get paid. Which means that even a niche artist with loyal fans could potentially be making money through streaming for years instead of just at the single point of sale. While the exact value of a lifetime of streaming versus a single purchase is still being established (if it’s of interest, I’d recommend economist David Touve’s look at the issue), at this exact moment in time this does mean that a ‘new’ band like Atoms for Peace will potentially make far less money upfront than they would on the old model of single transaction sales. If you’re on tiny label and need a lump of cash to help fuel your new album, touring etc, then it’s going to be a challenge if you’re counting on just streaming royalties. But the point still stands that this is likely to change sooner rather than later. Spotify and its direct competitors are volume businesses and the larger they grow, the more smaller, newer artists will get upfront and potentially over time.

Bit of the hard stuff

As much as I’ll raise my pom-poms in support of streaming platforms, as the numbers currently stand, we are still straddling an abyss (even if it’s an increasingly narrow one). But pulling music from streaming platforms isn’t a solution to the problem. Former Gang Of Four bassist Dave Allen has been very vocal in his rebuttals of Byrne, Godrich and Lowery, and rightfully points out that all three are failing to accept we’re in the middle of a transitional state where new markets are being formed and evolving. And like any new market, you can’t wilfully ignore what users are telling you they want in the hopes they’ll somehow revert to an outdated system that was more lucrative for you. No other industry would tell you that ignoring what your customers want is a good idea. The bottom line, and what’s been most lost in the debate this year, is that for most listeners it’s not a choice between streaming or buying music.

It’s a choice of streaming or stealing.

For many music lovers I know, their first experience with Spotify was a revelation, like suddenly being given access to the great cosmic jukebox they previously could only dream of. My 62-year-old father understood this when I showed him Spotify a few years ago. Outside of radio, it’s now his sole means of listening to music, and he’s a paying subscriber. This from a man who regularly asked me to grab albums off Napster for him at the start of the century.

And that’s where the real power of platforms like Spotify, Deezer and Rdio lies. The true appeal of Napster when it first launched wasn’t simply that it was free music, it was the fact that you suddenly had access to huge libraries of music almost on demand. Spotify and co. have beaten the Napsters by removing the ‘almost’ and provide music literally on demand. And it’s done through services that only allow you to listen to official releases and every play equals money earned – something that isn’t always a guarantee on streaming video platforms.

As a defence, some of Spotify’s supporters have attempted to argue it exposes listeners to music they might eventually buy. Byrne, in his widely shared piece, couldn’t fathom why the average listener would buy if they already have it in front of them on demand, especially if they’re able to save that music to their phones for offline listening (which, again, you can do on streaming subscriptions). On that, I agree with him, as does Dave Allen. And with new streaming services set to launch in 2014, most notably the Dr Dre backed Beats and a streaming subscription service from YouTube, all of it points to a likely future where streaming digital music, not buying, is the norm.

Billy Bragg recently said "Artists railing against Spotify is about as helpful to their cause as campaigning against the Sony Walkman would have been in the early 80s". He’s right, and the reality is that in the short term, smaller, newer acts will simply have to keep struggling along to find a way to survive, something that isn’t exactly a new experience for independent musicians. What is likely to emerge in 2014 is a larger debate between artists and labels over royalty rates from contracts written in the analogue era. It’s already started in Sweden. A group of musicians in Spotify’s homeland are filing a lawsuit against various labels over their split of Spotify royalties.

The debate will continue in 2014. As it should. Progress is something that should always be met with a close look at how it impacts all of us. But for those feeling guilty for their use of Spotify or Rdio or Deezer – don’t. Napster was a disruptive force, but we’re now faced with a model that may well be a solution to the problems it caused, or at least the start of one. Don’t forget, radio executives once dismissed TV as little more than a passing fad, and in the early 80s it was claimed cassette tapes would destroy the music industry. Things evolve and we adapt. Ever the story goes.