For a while I couldn’t put my finger on what was so damn appealing about the new Finders Keepers release, Tape Recorder And Synthesizer Ensemble by the never before heard of synth pop group T.R.A.S.E.

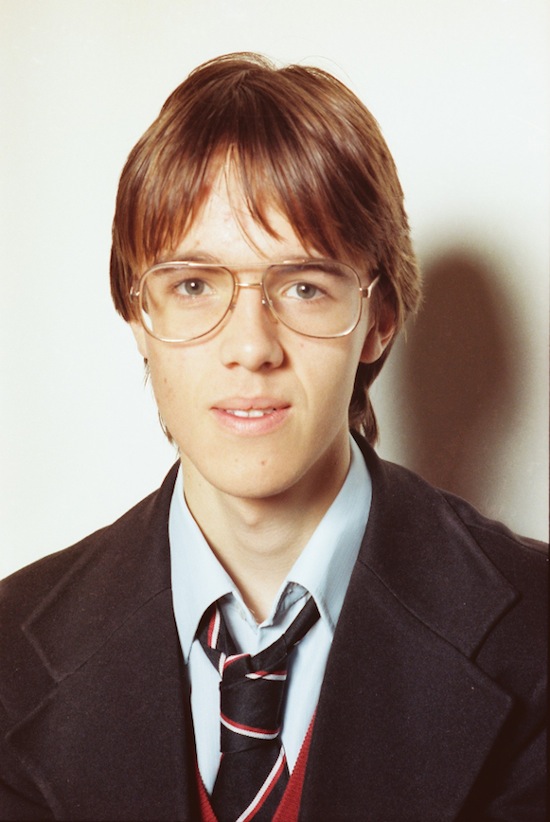

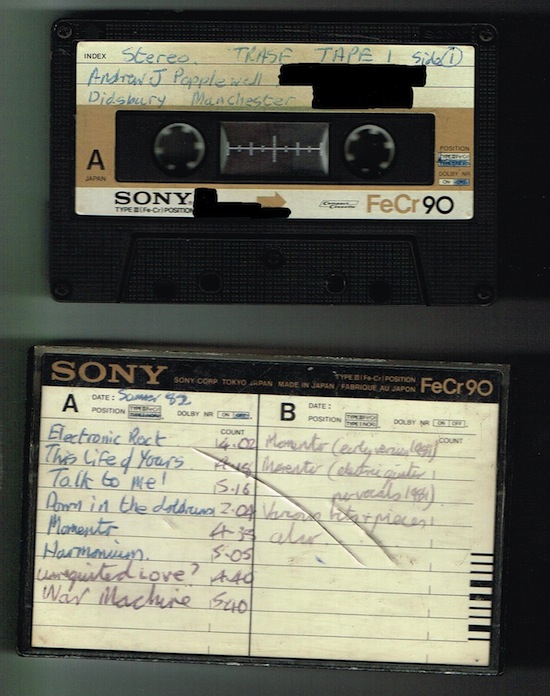

Sure the back story was pretty amazing. In 1979, a 14-year-old called Andy Popplewell started building his own six track mixer from a blueprint in an electronics hobbyist magazine. After it was finished he graduated to constructing his own synth before he turned 17 and then wrote a synth pop album in his mum’s garage and recorded it himself between 1981 and 1983; making one single cassette copy. Then due to a chance meeting with Andy Votel 30 years later in 2012, that cassette – not even a demo really as it never got sent to anyone – has now been released as an album.

And it doesn’t hurt that the album is actually good. The booming and moody homemade synths, icy syn drums and scratchy guitars call to mind album tracks from Tubeway Army’s self-titled debut as well as the instrumental sections of Replicas, not to mention Metamatic by John Foxx and sections of Travelogue and Reproduction by The Human League; albeit versions captured on two track (sometimes bounced down to three track) recordings in a mum’s garage in Didsbury in the early 1980s. But the low-fi recording adds to the recording not subtracts, giving it more of a fetish-worthy cold wave ambiance.

And some of the songs are better than good. When you listen to the track ‘Harmonium’ with it’s tape echoed guitar scratching and moody synths, you wonder where on Earth this slice of pre-shoegaze, pre post rock, outsider synth pop electronica has come from exactly.

But more than this, I realised after my fifth or sixth listen to this LP that someone had looked inside of me and realised one of my childhood dreams (by proxy) without me even having to ask. (Which pretty much means Andy Popplewell has realised the childhood dreams of thousands of others as well, I guess.) For I’d totally forgotten that when I was in school, this is what I dreamed of. Getting a band together that sounded like Ultravox! or OMD. Making synths. Writing songs. Recording an actual album that sounded like it did in my imagination. Doing the artwork myself. Doing it all just so I could say I’d done it. Just for the craic. It’s like looking across the multiverse and seeing the version of reality where I had the aptitude, the inclination, the inspiration, the talent and the energy to get it all done before hitting the age when being in band becomes all too real and ends up being about practice, success, ego, the slog and all of the distractions.

And there it was all along, on a single cassette, in a file, in a box, in an attic, in a house, in Greater Manchester: the proof that Andy Popplewell had already done it for me, done it for you as well probably, and done the whole thing like a fucking boss.

Whereabouts did you grow up?

Andy Popplewell: I grew up in Didsbury, Manchester. And I’ve lived here most of my life apart from the three years I worked for the BBC in London. I’m a Manc through and through.

In a bad turn of events for you, your dad died when you were ten years old. This must have been devastating.

AP: Yes it was. It was brutal. I used to play chess with my dad every night. After tea he would have a cigar or smoke his pipe and we’d play chess. I used to play football with him. And then my mum walked in one day and said, ‘Your dad’s dead.’ And that was it. No warning. No goodbyes. It was brutal. I don’t want any sympathy for it. It happens a lot to a lot of people. If you’re a parent and you have to give that information to your children, just imagine the damage done, psychologically speaking. Looking back – and hindsight is a great thing – the scars are there. You just end up thinking about what would have been, would I have made the same decisions, would I have ended up being the same person? And these are questions that I suppose will never be answered. You just have to muddle through. When I was a kid at school it was very difficult. Back in 1975 there was a stigma attached to it I guess. The teacher in my class at junior school said, “Never talk to Andrew about this ever.” And one of the kids sent me a letter – which my mum saved for me – saying that she disagreed with this and that she was sorry my dad had died but I didn’t see it until about 15 years later. It’s very different how people deal with bereavement today.

Where did the interest in electronic music come from? I believe your school was very important in fostering this interest…

AP: School was brilliant. Obviously we didn’t have a lot of money in those days, the mortgage got paid off because of life insurance but we didn’t have a lot. We had a “cardboard box corner”! Our imaginations were always nurtured. We were always allowed to think and create things. Me and my brother John just used to build things because in those days you couldn’t really afford to buy them, so you had to build them. I used to listen to radio a lot – Piccadilly FM. I just listened to music all the time from the age of four. And I listened to anything… classical or pop music. I had one of those stacking record decks which I was fascinated by. I went through the entire record collection in the house, 78s, 33s and 45s. I heard electronic music first on the radio. Kraftwerk. Vangelis. Giorgio Morodor. The Human League. John Foxx. Gary Numan. All those electronic pioneers of the late 70s and early 80s. It just did something for me. And of course in those days there were magazines flying round on the subject like Practical Electronics and Elektor and I started buying them. It piqued my interest. I thought, “I can’t afford to buy one of these synths so I’ll try and make one.” The beauty of my school – Parrs Wood High School in East Didsbury – was that it had a full engineering workshop. They were running lathes, milling machines, filing, anything to do with woodwork and metalwork I was doing all this stuff at 14. And I thought, “I can put these skills to use to do what I want to do.” So I had to learn electronics from scratch. Luckily for me my brother who was two years ahead of me was good with electronics and he really helped me out a lot. I copied the designs from the magazines, I learned how to make circuit boards myself and then assembled them. When they didn’t work, my brother would come in and help me work out what had gone wrong. We had access to the school’s physics labs, which was kitted out with equipment to test it all, oscilloscopes and oscillators. Fair play to the teachers; they were brilliant. I built everything from first principles. The six channel mixer if you look on the front cover of the album you can see it there. I built that from first principles in metalwork. I sourced the components by mail order and electronics shops and I copied the instructions. That was one of my first projects. It picked up radio really well [laughs] until my brother sorted that out. Again I was very inexperienced and there just wasn’t the information that there is out there now and I’ve been an audio engineer for a very long time. I learned a lot at the BBC, they gave me the professional training that I needed which I didn’t have when I was a kid. But I’ve always had this aptitude for practical things. I was taking cars apart when I was in my late teens and early 20s, stripping gearboxes, stuff like that. I had an innate curiosity.

What about the synths you made?

AP: With the Chorosynth that you can see on the cover of the album, I pictured the case for that in my mind, put it onto a blueprint, worked out what I needed in terms of front panel, user interface i.e. pots and switches, and after buying all the components from various electronics suppliers, I put it together. Alright, it didn’t work first time but after a while it did and this meant I could make music. We sort of improvised. Improvisation is how I work today. Improvisation on top of formal training. The formal training is important for what I do now. If you’re working on expensive kit you’ve got to know what you’re doing.

There was something in the air in the late 70s in a very arts and crafts sort of way as regards electronic music. I think Steven Morris built a kit synth while Joy Division were still going in the late 70s…

AP: …Yeah and I think I know what synth it was, a Transcendent 2000, a mono synth. I’ve met Steven Morris and done a bit of work for him. I think I remember reading an interview about this. It was done by a company called Powertran and they did a polysynth as well designed by a guy called Tim Orr. The do-it-yourself thing really was in vogue at the time because some of these synths were so expensive… if you wanted to buy a MOOG or an ARP back in the day it was way outside my price range. I was a school kid doing two or three paper rounds and doing odd jobs just to cover the cost of what I built at home and it took up all of my money and all of my time. To be fair the teachers at school gave me bits of wood and aluminium to help me build the casings. I can’t thank them enough really.

Were you building all of this equipment with a view to making music or did T.R.A.S.E. happen later?

AP: It all sort of evolved. I used to bash out tunes on the piano in the back room of my mum’s. I’m not formally trained. I can’t read music. But I go by ear and feel. I like making noise. It’s odd. These ideas just poured out of me over 18 months, inspired by Numan, Tubeway Army, Human League. I can’t deny that I was highly influenced by those guys. I went to see Gary Numan play at the Apollo Theatre in Manchester on the Teletour in 1981. What really got me though was the single he released in 1979, ‘Cars’. That song is brilliant. I still think it is now. When I bought The Pleasure Principle it just blew me away. But all of that synth music sent shivers down my spine. I just wanted to do my own stuff in that genre. The whole thing with T.R.A.S.E. is very odd, I didn’t have any desire to be famous. Sure, when I was a teenager there is the ego and you want respect from your peers and you want to be a pop star and get girls, blah blah blah. That’s what everyone wants when they’re a teenager. It’s just part of growing up. But for me I just wanted to do it. And I did it. And now, 30 years later, people are buying it. Which I’m gobsmacked about! I’m still reeling from it to be honest! Even though the deal was done last Decebmer. Life is very strange. [laughs]

You started recording this material at home because you were only a teenager and didn’t have access to a studio. I take it a lot of it was recorded live but what techniques were you using to make the most of what you had?

AP: Well, I was splicing tape to make loops. There was no multi-tracking involved at all. I had two stereo reel to reel domestic tape machines which were not in peak condition I have to admit.

Could you do sound on sound with them?

AP: Well, most of the time I didn’t. There was one exception, the song ‘Harmonium’. That’s a very odd song. That was improvised. I’d learned about tape echo in 1981. I had a guitar and I’d learned a few chords and rather than playing the chords I was scraping the strings with a plectrum and with the tape echo it created this very interesting effect. I recorded that song in 1981 and I put the tape to one side. Before I did the album I was just messing about for six months, while I was still constructing the Chorosynth. I was essentially just constructing ideas. But the recording techniques were very simple there was no multi-tracking. I recorded the drums on one track and at the same time played live on the other track. I played it all back through the mixer onto the other tape machine and played live over that. So essentially I had three parts on the second machine. Sometimes I’d go a third time and master it onto another cassette. I’d bought the Sony TC-FX2 cassette machine from Comet in Northenden brand new, so at least I had a decent bit of mastering kit. So everything was second or third generation and played live, apart from the drum machine of course. I came up with a clever way of triggering the synth by the drum machine clock clock so when you held a note down it was in time with the click on the drum machine. From there I just came up with a load of ideas. For recording ‘Harmonium’ I had a Roland string synth which I borrowed off a mate from school and I was just ad libbing. I literally lifted the tape off the erase head and added the drum machine on randomly, trying to get a decent drum sound. It was all very trial and error. It was very painstaking. If I made a mistake I had to go back to the beginning and start again. There was no multi-tracking and no MIDI – MIDI hadn’t been invented. It was hard work. In three weeks I had eight tracks.

I really like the track ‘Harmonium’ – it’s not just synth pop, it’s very reminiscent of what would become post rock as well.

AP: This stuff just poured out of me, I wasn’t really thinking about labels for it. If people buy it and they like it, I’m very happy. I’ve never met Gary Numan but I was reading an article on him and I can relate to the guy. I could sit down and have a cup of tea with the guy because he’s been very candid about his problems he’s had with his life because he’s got Asperger’s. I did some online tests… I didn’t even know what Asperger’s was five years ago. But I’m on that spectrum. And also someone who I know who has an autistic child said, "Andy, you’re high functioning Asperger’s." I didn’t even know what she meant but I do now. They say, “Know thyself” and I do now. I’ve sussed it. I know I can be a bit eccentric but that’s part of who I am.

What about other music you were into?

AP: I didn’t stop with Gary Numan. I like a lot of Depeche Mode. Some of their later albums like Violator and Songs Of Faith And Devotion are really from the heart. I’ve watched YouTube clips of John Foxx playing live recently and I loved it. I was really into Ultravox! when he was the singer, I bought Metamatic when that came out. He was so ahead of his time. I grew up in pioneering period – punk, post punk, synth pop. The Sex Pistols, Public Image Ltd… It was almost like this was a nexus point in music and I feel privileged to have lived through it all.

Did all of this experimentation at home and in small studios lead on to your work at the BBC?

AP: No, I was mitering the BBC when I was 16. I have an engineering mind. I wouldn’t say I was born an engineer but I have an enquiring mind. I always think, “How does that work?” I wanted to be an engineer and the BBC had a training programme, I wrote to them when I was 18 and I got the job! It was like a sandwich course back in those days. You did three months training and then three months on the job with guys who were 20, 30, 40 years older than me and then back for more training. These guys were the guvnors and I just soaked up as much information as I could but I wasn’t really happy with London and the commuting. It just wasn’t for me.

How did you get into the specialised field of tape restoration?

AP: The tape restoration business started in about 2004. I knew about gluey tapes in the1990s and it was a problem and Ampex used to bake tapes as a free service. No one ever asked me to repair tapes, it was just studios, recorders, mixers, stuff like that. But then in about 2004 someone approached me and said, “I’ve got all these tapes I can’t play any more…” So I went on the internet to find out what other people were doing. The Americans have been doing this for some time. There are various methodologies, so I chose one and built my own baking machine out of a hair dryer and a timer and I tested it on some tapes that I had from the 1980s. I prototyped everything using my own tapes so I didn’t destroy anyone else’s music and tapes. And it all worked! And word got out.

How did you meet Andy Votel and everyone at Finders Keepers?

AP: Chance meeting really. I work for a company up here called Advanced Media Restoration. I’m helping them out at the moment to expand their business. They have every tape format apart from a couple which are very rare indeed. They’ve got a huge archive here. Andy booked a suite to transfer a couple of quarter inch tapes. We were just talking. Just two weeks previously I’d been going through my own archive transferring the tapes – and I’ve been making music for about thirty years now on and off, so my own archive is pretty big. Andy asked me if I’d ever done music and I said, “Well actually I’ve just transferred my own archive. Have a laugh at this mate.” He was stunned. I just said, “Here’s all the files. Here’s all the paperwork. See what you think.” I just gave him the whole lot. He and Doug Shipton got back to me – I’d dug out some photos by then. I found some negatives – the picture on the front of the album was taken by my mum on an old instamatic in our garage. They offered to release it and I was dumbfounded. “You’re telling me you want to release this stuff I did 30 years ago?” And they said, “Absolutely.”

Have you still got the Chorosynth?

AP: I’ve still got it but it’s in need of restoration. It’s in a state electronically. The pots and switches are all worn out. For me it’s a standard servicing job – I’ll re-pot it, re-switch it, re-cap it, upgrade the power supply, clean all the keyboard connections and see if it still works. Most people don’t realise but it was a pain in the arse to retune. It kept on going out of tune. I had to coax those tunes out of it. It’s a unique instrument. There’s only one like it on the planet, as far as I know. It was all fully customized.

Are you pleased with the response the album’s been getting?

AP: It seems to have struck a chord with people and I’m having trouble getting my head round it. I’m a bit out of touch with the music industry at the moment. I enjoy peace and quiet to be honest. Andy and Doug have done a brilliant job on it. It’s a wonderful looking record.

Has this impacted on you as regards to your music? Are you going to make any more or reissue any more?

AP: Well, the deal with Andy and Doug was that I gave them 27 tracks and said that they can do what they want with them as long as they keep me in the loop. I mean I trust their judgement on this. Musically… I don’t know… it’s all on the backburner really at the moment. I did a lot more music but it wasn’t really the same as T.R.A.S.E. so I don’t know really. That was me letting out my emotions but I guess I got more into writing tunes and melodies.

You’ve said that you’ve had psychological problems over the years. Would you say that your interest in music has helped alleviate them or helped you understand them better?

AP: Yes. Music should touch you in some way, either emotionally, spiritually or intellectually. It should make you go, “Wow.” I find that a lot of music these days doesn’t have the same impact for me. I’m not saying it’s bad – music is music. But I feel that nowadays there are unlimited options. Unlimited plug ins. Unlimited channels. Unlimited amounts of music you can access. It’s just that when I was making music I had a lot of constraints on me and I pushed the limited equipment I had to the absolute limit of what it would do. And sometimes I think working within constraints can make you more ingenious and more creative. But that’s just my opinion.

Tape Recorder And Synthesizer Ensemble is out now via Finders Keepers