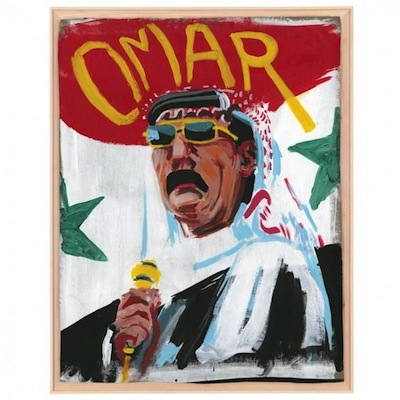

You can almost read the artwork of Omar Souleyman’s releases since his Western debut, 2007’s Highway To Hassake, as a prophetic storyboard. Those first two Sublime Frequencies releases still very much frame the man as the mysterious market stall cassette tape singer, while Jazeera Nights and Haflat Gharbia: The Western Concerts show Souleyman in sharp focus, emerging from the fuzzy analogue corners of the world as a tangibly real and living legend. In the latter he was already and perhaps tellingly standing defiant, his back to us as he faces the mirror to adjust the signature keffiyah. Now in 2013, the cover of Wenu Wenu quite literally paints the man as an icon, Spencer Sweeney’s sprawling graffiti headed with the single word: "Omar". The singer’s first name alone is now more than enough introduction.

Reactions to Wenu Wenu have already been for the most part positive, highlighting the newly clean production, and praising the continuing thrill of listening to the singer and his band play. Aside from the predictably excellent music, Wenu Wenu should be seen as something of a watershed for both Omar Souleyman himself and for western popular music at large. It’s satisfying seeing Souleyman as a labelmate of Django Django, Laura Marling and John Maus on Domino’s Ribbon Music imprint, continuing the breaking of a ‘western’ musical hegemony. It’s worth considering Slavoj Žižek’s claim that "we are effectively approaching a multicentric world", and hoping that this sort of jarring cultural penetration is going to become (hopefully) more prevalent.

Souleyman is the first major Syrian (or indeed Middle Eastern) musician signed to a British indie like Domino. Most striking is how he’s made this westward journey without sacrificing any of what made him quite so special in the first place. What has changed, though – and this is perhaps a key input from Wenu Wenu‘s producer, Four Tet’s Kieran Hebden – is the removal of that previously all-encompassing grit, decay and delay from the proceedings. The opening title track sets the precedent, kicking in with synth stabs before a face-melting saz solo and Omar Souleyman’s now crystal clear cries of "wenu wenu wenu?" ("where is she?"). The immediate clarity of the vocals – there remains of course some obligatory semblance of echo – in fact adds to, just as much as it detracts from, the urgency of the track. The music itself has certainly shifted its shape under Kieran Hebden’s guidance, but it’s lost none of that unavoidable, throttling, passionate tenacity.

In the mix, the instruments are now split, no longer the fuzzy analogue cassette tape that congealed into one impenetrable mass – and while this does cost the music some of that thrift store charm, it giveth in equal measure, particularly as call-and-response often plays such a vital role in these songs. The title track, ‘Warni Warni’ and ‘Nahy’ are perfect examples, as Souleyman converses almost directly with the band, swapping lines with Rizan Sa’id’s synths and flute samples, or shouting down searing saz solos like a sparring partner.

It’s certainly Omar Souleyman’s most user-friendly listening experience. Hebden’s democratic production style and mixing board economy, valuing every instrument equally, makes it less relentless than its ancestors. The keyboard rhythms and trancey samples that bed the majority of these songs were previously warped and muted, deadening that potentially fatal association with low grade dance music, but somehow Wenu Wenu manages to keep any such preconceptions at bay. If anything, the club-ready low end finally packs a much-needed punch that was arguably previously lacking. The countless additional synthetic percussion lines on ‘Yagbuni’ or the pounding kick drum at the heart of slow jam ‘Mawal Jamar’ show off Hebden’s ability to push and pull listener-focus, the former similarly demonstrating Souleyman and Sa’id’s almost superhuman marriage of composition and improvisation.

Omar Souleyman’s metamorphosis on Wenu Wenu is bound to raise some eyebrows, and perhaps lose him some of the musical explorers and global cassette collectors who made up his initial fan base in the West. Yet this clearly doesn’t fit with his ambition. This music transcends barriers of language and culture, able to inspire fans in both East and West – and at the same time, can help dissipate those increasingly outdated divides.