Such has been the long shadow of influence cast by the Cocteau Twins that it seems strange to think that even they had heroes who’d made a profound and indelible effect on them. Even more curious an idea to consider is that their primary role models were the Dadaist and chaotic car-crash that was The Birthday Party, a band hell-bent on leaving a trail of pandemonium, confusion and destruction in their wake as they dragged the battered and bleeding remains of rock & roll with them by its heels. And yet it’s all there in their 1982 debut album, Garlands. The bloodied finger trails of Roland S. Howard’s cheesewire guitars are daubed all over songs such as the title track, ‘The Hollow Men’ and ‘Wax And Wane’ as conventional notions of what a guitar could and should do in the seismic wake of punk are thrown to the wind like so much discarded garbage.

It’s a point worth noting as, just over a year later, the Cocteau Twins – truncated to the duo of sonic architect [see me after class, Ed] Robin Guthrie and singer Elizabeth Fraser following the departure of bassist Will Heggie after a 46-date tour with Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark – made such a huge leap forward that it not only showed where they were going but also did much to relegate their debut to the unfair status of a half-remembered long-lost relative. But those influences still loomed large over their second album, Head Over Heels, as the possibilities of sound were explored to create a new vernacular. And it’s within this world of aural exploration that rhythms are subverted to add colour and texture while in Elizabeth Fraser’s soaring and ethereal voice and damn near incomprehensible lyrics that a unique vocal delivery is announced to mesh with the instruments to birth an innovative delivery.

And what a difference a year made. In such a short space of time, Elizabeth Fraser’s singing had developed from a weapon given to frequent warbling to one of the most idiosyncratic voices of her generation. Navigating its way through sense and nonsense, heaven and hell, pleasure and pain and all points in between, Fraser’s voice became just as much an instrument as those played by her cohort. Though her speaking-in-tongues delivery had yet to fully develop and recognisable words appear throughout the songs like the briefest of glimpses of form in a swirling and dense fog, her lyrics are more like punctuating syllables that simultaneously blend and bounce with and against the instrumentation going on around her. As displayed by the fact that no two lyric websites can agree what’s actually being sung, the actual lyrical content doesn’t matter here. What is important is that, in tandem with Guthrie’s wall of sound production, a blank canvass is presented to the listener in order to project his or her own imagery and meaning.

It’s a device employed as early as opening track, ‘When Mama Was Moth’. Simply by delivering the opening words, “The sunburst and the snow blind,” Fraser is seemingly pointing us in right direction yet leaving us to determine quite what that direction is. To these ears, it makes sense of the huge percussive crashes that usher in the album; these aren’t drums but icebergs smashing into each other and dropping huge chunks of debris from their frozen hulks. Guthrie’s multi-layered and heavily reverberated guitars evoke frozen panoramic sweeps where distance becomes an irrelevance while the tinkling arpeggios could easily be the first flurry of winter snow.

Similarly the imagery of a sugar hiccup is given a beautifully hallucinogenic quality thanks to a lyrical juxtaposition of inconvenience and delight while the guitars shimmer and wink with the allure of hundreds and thousands on a celestial birthday cake. The swooping bass that underpins the song pushes and pulls whilst maintaining the ability to sooth and comfort. Theirs is a confusion that makes perfect sense.

Yet despite the mangling of conventions, there remain moments firmly rooted in songwriting tradition. ‘In Our Angelhood’ probably fits the bill best and it’s a track that wouldn’t have sounded out of place on Siouxsie And The Banshee’s Kaleidoscope. Yet for all of its straightforward dynamics, it serves to highlight the sheer swirling madness of ‘Glass Candle Grenades’ or the creeping menace and sense of threat that pervades ‘The Tinderbox (Of A Heart)’.

But it’s with closer ‘Musette And Drums’ that the album achieves a climactic flourish that tugs and pulls at the emotions and senses. Cinematic in scope, Robin Guthrie’s guitars sweep and scythe with determination and a power that threatens to overcome the drums that are buried further down in the mix. But it’s with the drop to the chorus that the song shifts a gear as the guitars relax their vice-like grip to offer a series of chimes while the keyboards take on the role of a digitised orchestra. As the track progresses, Fraser’s voice is split into two distinct sections before allowing Guthrie to take off with a series of squeals, shudders and shakes that transposes the divine sounds of Phil Spector into another decade.

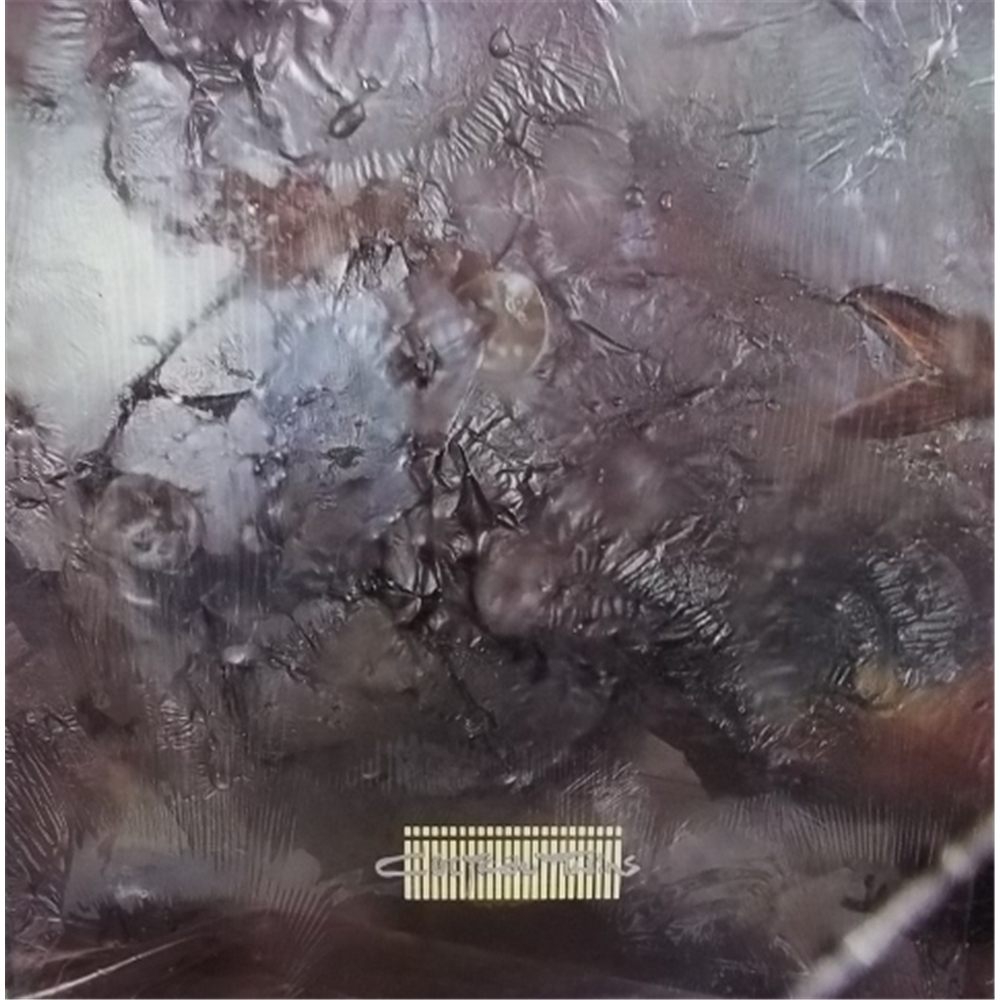

But there’s more to Head Over Heels than just music. Crucial to the album was the packaging and art design by 23 Envelope, the graphic design partnership of Vaughan Oliver and Nigel Grierson. This was perhaps the first of the album covers that truly gave label 4AD the imagery that it became known for and it was a relationship that would seriously rival that of Peter Saville and Factory Records. This was a visual aesthetic that mirrored the contents of what was contained within the sleeve and in this respect, the glacial tones and images of what appear to be frozen leaves preserved in permafrost while the droplets of water that have randomly fallen on them are crystalised tears forever captured for posterity. Save for a band logo towards the bottom of the cover, this is a wordless image that still manages to speak volumes. This wasn’t just a record that was held in eager hands but also a statement and package that meshed sound and sight as effortlessly as the fusion of musical ideas contained with the grooves of the vinyl.

To listen to Head Over Heels from the vantage point of 30 years is to rediscover an album that at once is a bold step forward in establishing a unique identity in British independent music as well as building a bridge to a place of odd and strange beauty. It doesn’t matter now any more than it did then that the songs are shrouded in a wilful and perverse mystery that will forever elude interpretive consensus. What is important is that this remains a unique collection of music in a body of work that’s often been imitated but rarely equalled. Moreover, the Cocteau Twins’ power to enthral and beguile with their second album remains undiminished and subsequent visits prove as enriching as when they first revealed themselves to an unsuspecting world. Head Over Heels rarely tops anybody’s list of favourite Cocteau Twins albums but it’s probably the one that should command the most respect. Created in the face of adversity, the album remains a perfect example of how the influence of heroes doesn’t have to mean creating a facsimile; it means sharing an aesthetic and a determination to forge ahead, develop and grow. As Mark Lanegan pointed out to The Quietus, you can’t escape your influences. Quite so but Head Over Heels demonstrates emphatically how to transcend them.