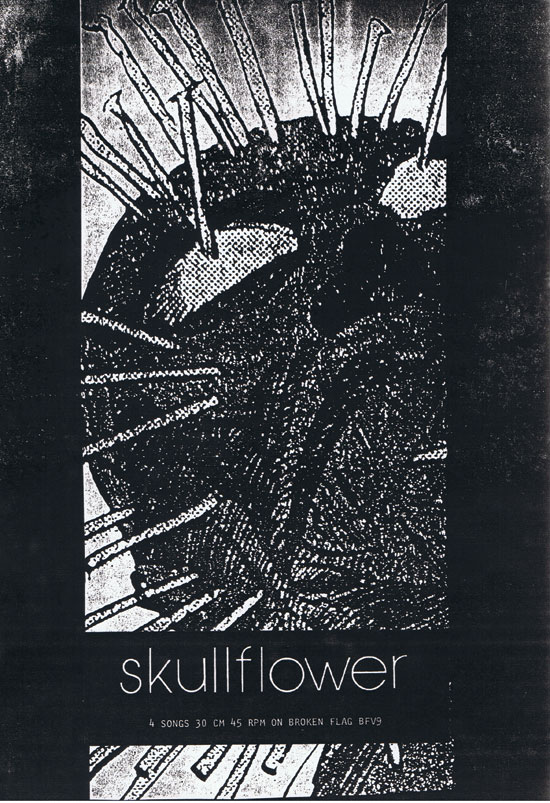

For more information on the Skullflower reissues visit Dirter’s website

…somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

‘The Second Coming’ W.B. Yeats

Skullflower were the sound of balefulness. A sneer turned into noise.

Slouching out of the squats of North London in the mid 80s, moving among the purveyors of noise, power electronics and industrial – while not really sounding anything like them – they mixed with the acid heads, the occultists, the drop outs and the horror freaks, distilling the bad vibes up into an anti-aesthetic.

Their music, from their initial phase, was a sickening edifice built from intransigence, tiredness, intolerance, angst and anger: a pair of taunting scare quotes hanging round nothing, framed by void. Untutored to perfection, their atonal no wave, post post punk, un-free noise rock, was the blueprint for something terrible and slightly brilliant that never really came to pass… maybe because no one was listening… maybe because they forgot to tell anyone what they were doing in the first place.

Sure, you can hear what sounds like their influence in the disparate likes of Godflesh, Terminal Cheesecake, Health, Khanate and Lightning Bolt (Justin Broadrick was certainly a fan, he released some of the band’s material on his hEADdIRT label – whether the others have even heard of Skullflower is a different matter however, I have no idea – you’d have to ask them) but nothing sounds quite like this first incarnation. (You can also draw very loose parallels to the Butthole Surfers at their most fierce and muscular – all sterile gated drum reverb and howling guitars – and Sonic Youth at their most urgent and clangorous, but these are only tangential comparisons at best.)

feature continues after sleeve art

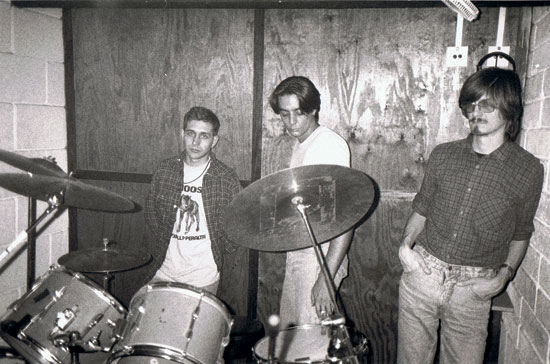

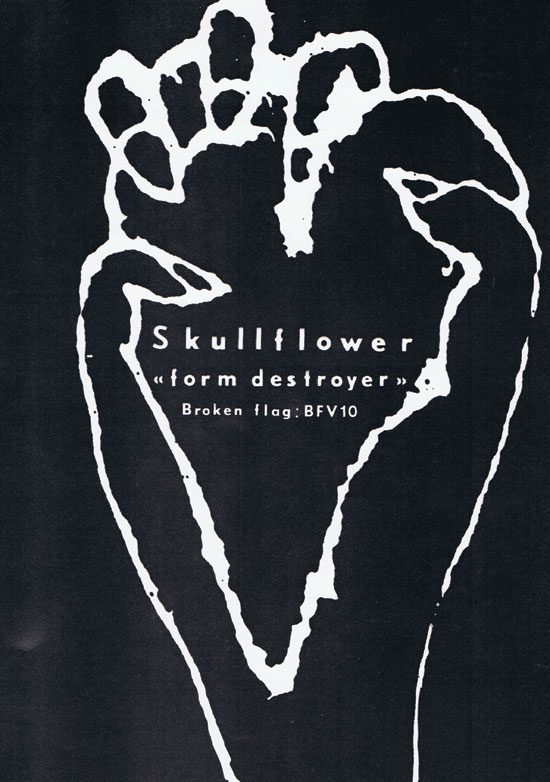

The band formed in 1986 and, in their first phase, operated round the core of Matthew Bower, Stefan Jaworzyn and Stuart Dennison, with Gary Mundy of Ramleh becoming a permanent member soon after. Who actually appeared on which track beyond this seems to have depended (to a certain extent) on who was in their Brixton rehearsal room when the tape was rolling.

Notable auxiliary members during this period included Mundy, Stephen Thrower of Coil, Alex Binnie and Anthony Di Franco. The material that they released during this period, BirthDeath (1988, Broken Flag), Form Destroyer (1989, Broken Flag), Xaman (1990, Shock), Ruins (1990, Shock), as well singles and unreleased material, have just been reissued on Jaworzyn’s recently reanimated Shock label, across four CDs KINO I – IV, with everything remastered and accompanied by sleeve notes.

They’re great albums. They document a bunch of people, who initially really have next to no idea what they’re doing, stumbling across a unique and unsettling sound; but we get to stay with them as they seize control of the process, observing them get better and better at what they do before splintering under the pressure necessary to create this suffocating racket. (Jaworzyn left in 1990 in relatively acrimonious circumstances, carrying on further out into the realms of the avant garde with solo material and as a member of the free rock bands, Ascension and Descension. Skullflower carried on heading out into uncharted realms of free noise themselves until 1997. They reformed in 2003 and remain operational to this day, playing live and releasing material on Cold Spring.)

There being little reliable information online about the band (apart from Matthew Bower’s Skullflower blog), I phoned Jaworzyn recently with the intention of getting some background information to use while reviewing the albums, but the quick chat turned into a 90 minute interview and the review got binned in favour of this feature.

(Should you be interested, my review would have gone something like this: these albums are fucking great, you should buy them – even though they’ve sent my tinnitus off the hook. A lot of TV commentators take the 1960s to be a short decade in the Eric Hobsbawm sense, claiming that it ended in murder at the Altamont Speedway on December 6, 1969. But how much resonance does this actually have for those watching their TVs in the UK? In Britain the last vestiges of 60s liberalism and utopian counterculture were ground into the dirt during Margaret Thatcher’s second and third terms in office, between 1983 and 1989. The 1960s were the most forward looking and inclusive time in living memory, promising a new dawn in civil rights, an end to racism, misogyny and homophobia, as well as fair treatment for the working classes, for the first time ever. The spirit of the 1960s was still just about alive by the 1980s, with radical political movements such as anarcho-syndicalism still promising that power could be seized from the capitalists and distributed among the people on the street. As much as they might seem like unlikely hippies in the sense of dress and music, politically and spiritually bands such as CRASS and Napalm Death were 100% children of the 1960s. This may seem far-fetched – and in some ways it is – but Thatcher, as well as setting her sights on crushing this country’s heavy industry and curtailing civil liberties, wanted to turn the clock back to before the Swinging 60s, believing in a mission statement which she summed up herself as: “Go back, you flower people, back where you came from, wash your hair, get dressed properly, get to work on time and stop all this whingeing and moaning.”

Skullflower’s Xaman, the Jesus And Mary Chain’s Psychocandy and Godflesh’s Streetcleaner are the soundtrack to the death of 60s liberalism and optimism. They sound the retreat into nihilism and despair, which is not just to say that they are violent and inward looking, but that they also viciously parody the sun dappled psychedelia of 1967. This is the brown acid really kicking in. If you like this sort of thing, you’ll really like Kino I – IV a great deal. Instead of saying, well, it sounds a bit like a cross between early Big Black, Godflesh, Scratch Acid and Cabaret Voltaire, I’m going to make a spiritual comparison instead of a sonic one. At their best, these discs feel like one of those documents where you can sense the mental sickness, obsession, narcotics and physical unhealthiness that’s gone into a record, like you can with Electric Wizard’s Dopethrone, Eyehategod’s Dopesick, Mayhem’s De Mysteriis Dom Sathanas and even Sly & The Family Stone’s There’s A Riot Going On. To web literalists I should point out that it doesn’t sound like any of these albums; it sounds more like a cross between early Big Black, Godflesh, Scratch Acid and Cabaret Voltaire. But most of all, everyone needs a song called ‘Bo Didley’s Shitpump’ in their lives, right?)

feature continues after sleeve art

From what I understand, the genesis of Skullflower out of the groups Pure and Total seems quite convoluted. Can you break it down simply for me?

Stefan Jaworzyn: Pure was a trio that Matthew [Bower] and Alex Binnie had with another guy called Alex on bass. They were a performance art-ish, Virgin Prunes-y, confrontational type thing that was happening in the early 80s. They played quite a lot of gigs. Alex laid his bass on the floor and kind of scraped at it; they had a few actual songs. Matthew and Alex Binnie would paint themselves and roll around on the floor and do all kinds of shit like that. Total was originally a solo bedroom project of Matthew’s. At some point early in [Skullflower’s] history we called ourselves Total because we couldn’t think of a name but that didn’t last for very long. Coincidentally the live gig which is available on the 12” as part of the limited edition set, was while we were called Total. But we had numerous other names that we kicked around, and when we eventually called ourselves Skullflower, Matthew went back to calling his solo stuff Total.

Skullflower started in early 1986, and it was Matthew, Stuart Dennison and me, just as a trio. After we did a couple of rehearsals we realised that we needed another instrument, so Alex Binnie came in playing bass. At that point Matthew wasn’t really playing anything, he was programming drum machines and making various noises. Matthew must have asked Gary [Mundy] to come along and we all slotted together really well. We did one proper recording with the five of us, and not long after that Alex Binnie decided that he didn’t want to do it anymore and Matthew started playing bass, so that early nucleus of Skullflower was Matthew, me, Stuart and Gary. So we were a quartet for the first 12” and a lot of Form Destroyer. During the time we were doing Form Destroyer Stuart went AWOL for a bit, so different people came to sessions, including Stephen Thrower, who was in Coil at the time and was a friend of mine. During those first three years, the core was basically Matthew, me, Stuart and Gary… give or take one person depending on who did or didn’t turn up.

What about socially? Give me an idea what kind of people you were and how you all met?

SJ: Ah, Jesus! Funnily enough I have a CD of my early solo stuff coming out [on Shock], and I’ve just been writing notes for it which has made me remember a lot of this stuff. I’d met Alex Binnie while living in Cardiff in 1982. I was in a noise trio with Robert Lawrence who ran a cassette label called Quick Stab, some of whose stuff has re-emerged recently. First we had a trio, then Robert left and it was just two of us. Binnie was at college in Cardiff and we’d play in an art venue there – him and his friend Eddie came over after we played and talked to us. Nobody liked us. We dressed in black and played with our backs to the audience, blah blah blah. Alex Binnie said he thought we were pretty entertaining. He put us on at an arts event in Cardiff and Matthew Bower came up to play at it. That was the first time I encountered him, which would have been at some point in 1982. I didn’t really get to know Matthew until I moved to London, which was during 1983. Alex Binnie convinced me I’d be better off down here than up there. And I ended up living in a squat just up the road from Matthew so we got to know each other more.

There was that London noise scene with Broken Flag, and we gravitated towards it and met a load of those people. Philip Best was crashing on the floor of my squat for a bit. A lot of people who are still active now were just finding their feet then. I guess we all got to know each other, not because of popular opinion, but because there weren’t that many of us around doing noise, noise rock, power electronics or whatever you’d want to call it at the time. Matthew must have known Gary Mundy from the early Ramleh stuff – he used to go and watch them live. He had an actual ‘rockish’ band called Sulphur Of Lions at one point in the early 80s. Everybody was just around, but it was a much smaller world than one might think. It might have taken on legendary proportions since then, but it didn’t seem very legendary at the time. It was a relatively small world. Everyone knew each other and bumped into each other at gigs.

When did you first play a gig together?

SJ: Well, Skullflower only did two gigs during the four years that I played with them. There’s the one that’s on the 12” – and that’s the entirety of the gig! And there was the one in Brighton with AC Temple around the time Xaman came out – there’s a poster for it in the CD. Me and Matthew played a “fake” Ramleh gig in Birmingham, which I believe he put out on some CD a few years ago. Ramleh were supposed to play but Gary didn’t want to go, and me and Matthew went and pretended to be Ramleh! That was the only thing close to a Skullflower gig during that period of time. We were much lower profile than you might think. We didn’t get out much.

Is the previously unreleased material on KINO I the oldest Skullflower material there is?

SJ: Yeah. There’s a version of ‘Slaves’ from May 1986 on there which is the earliest [usable] stuff we did, as far as I’m aware. There’s another version of ‘Slaves’ from the same session which I didn’t put on the CD. That’s the earliest decent sounding thing I could find on my cassettes. I have earlier stuff, including something with Alex Binnie on bass, but we just didn’t think that the stuff sounded very good. [It was] a bad recording done on a Walkman in a rehearsal room. It just sounds terrible.

When you were listening to those five initial tracks, did it remind you of how the sound came together? Was it organic or was there any kind of discussion?

SJ: No. No. It just happened. It was pretty organic. There were bands that we liked but I don’t think I would say that it influenced us to try and make music like them. We were also limited to a certain extent by our abilities, i.e. none of us were proper musicians apart from Gary Mundy… he could play guitar “properly”. The rest of us were just self-taught. We couldn’t have written a song with a chorus if we’d had guns to our heads. Yeah. Organic is a good way of putting it, as far as the birth and gestation goes.

Well, in a very tangential way there are resemblances to UK music that came slightly later, like Godflesh, Loop, Fudge Tunnel and Terminal Cheesecake, and one or two early tracks bear a passing – but only slight – resemblance to early Sonic Youth, Butthole Surfers and Scratch Acid. Did you see yourselves as completely insular and cut off from all other forms of non-electronic music around you?

SJ: I don’t think we ever even thought about it in those terms or in that way, to be honest. We used to do these all night sessions at a studio called JTI under the arches at Brixton. Kind of a hell hole. We didn’t do gigs. We weren’t mates with other English bands. All the other stuff we liked was American, very old or experimental music. We certainly weren’t part of an English scene. Jonathan Selzer [Metal Hammer, formerly Melody Maker and Terrorizer] was always really keen, on the occasions that I’ve met him, to tell me that we were part of the burgeoning disaffected noise rock scene of the late 80s, but we really weren’t. I mean, yes, we were active at the same time, so if you were compiling English underground bands from around that period then, yes, you would say that Skullflower were part of it, because it makes sense and I can see why people would do that. But we didn’t have any contact with anyone else. We felt like we were operating in a void of our own making.

feature continues after sleeve art

You just described your rehearsal room as a “hell hole”. Would you say that you were making “urban” music. I mean this in its truest sense; i.e. were you making music as a response to your high pressure, high density surroundings?

SJ: I think so. I think it was… Matthew might disagree with me, so this is only my opinion… I think that the shitty Thatcher Tory days and the horrible oppressive feeling of the mid 1980s had a lot to do with the headspace we were in. And you have to remember we were still pretty young. We weren’t even full of piss and vinegar. We were just full of piss. Maybe we were just a bunch of angry psychotics, smoking bongs and playing music all night in a hell hole in Brixton. But I think that living in London in the 1980s, we’d all lived in squats, housing collectives and dungeons in North London. I think it had a definite effect – if not on the way we thought, then definitely on our subconscious outlook.

In the power electronics scene, which you were loosely affiliated with, there was a lot of provocation. Some of the bands would use imagery, art, lyrics and concepts which would irritate and offend even the most liberal of people…

SJ: [laughs uproariously]

…but in Skullflower you seemed to be completely removed from this. I was just wondering what your philosophy was when it came down to packaging, art and the way you presented yourself.

SJ: I would say that Matthew and Gary liked as much obscurity as possible. I think there was a definite urge at the time for people not to get an explicit message from us about what we thought and what we were about. We weren’t attempting to be confrontational in the same way that the power electronic people had been. I think you could say that for “rock musicians” we were pretty confrontational and unapproachable anyway. That was enough. We definitely didn’t have any interest in manifestos or doing things deliberately just to piss people off… other than the fact we were maybe the kind of people who just naturally pissed people off in those days. I don’t know. I did a long interview with Dave Kerekes for the Headpress Xerox Ferox book about when I edited Shock Xpress, and we talked about my anger and how it manifested itself in that magazine and how it used to piss people off. I had issues! [laughs] Well, I guess we all did, but it just came out in different ways.

Can you explain, for the uninitiated, what Broken Flag was and what its loose aims were?

SJ: Absolutely not. No. You’d have to talk to Gary about that. He had a label and that’s why we put those two records out on it. We liked Gary. He was our mate and in the band. But that was it, from my point of view, essentially.

You said that you shunned all publicity, but you did know some pretty big figures. You’ve already said that Philip Best was crashing on your floor. How did you meet Stephen Thrower from Coil?

SJ: I met Steve through doing Shock Xpress magazine. For a while I used to work in the very old Forbidden Planet Two on St Giles High Street, and that was kind of a focal point for anyone who was interested in horror movies and this and that. So I got to meet Steve through there, and through him I met Jhon Balance and Sleazy. We were quite good friends. And at that point we all knew Clive Barker. Coil were pencilled in to do the soundtrack to Hellraiser. So a lot of people knew each other. I knew that Steve played a lot of instruments, so when we were minus Stuart I just suggested that he might as well come along to a session. Philip Best I met because of where I lived essentially. There were two or three houses on Liverpool Road, just off Holloway Road, where various people lived. Matthew lived a few hundred yards down the road from me, and loads of different people used to come round and hang out. So through Philip I got to meet William Bennett. Everybody lived fairly close to each other. I wouldn’t say it was a social circle, but you’d just hang out round at each other’s flats because there wasn’t anything else to do.

It sounds like a really terrifying sit-com.

SJ: [laughs] It fucking well was. A terrifying sit-com without the humour. It was like Til’ Death Us Do Part populated by people with shaved heads and copies of Psychopathia Sexualis tucked under their arms. [laughs] The horror movie scene was probably slightly healthier. The people I met through Shock Xpress were probably a bit more normal. The two areas that I worked in did overlap a tad, actually. The horror movie thing and the weird music thing did overlap. A lot of people were into similar things.

The aesthetic is pretty similar.

SJ: Yeah, I guess so. And during this time, in 1984, the Video Recordings Act had just been passed, so there was a real underground feel to trying to see and collect videos of stuff that had been recently banned. So there was a thing about tracking down video cassettes of crappy horror movies that were getting increasingly more difficult to find because they had been banned by the British Board Of Film Classification. So it was another thing that the weirdos had in common. Weird movies and weird music.

So compared to most of the people who were hanging round in your peer group, you had more of a rock band line up; but you weren’t really a rock band in the way that most people would perceive one to be. Were there any kind of interesting instruments used, did you salvage or build your own electronics, did you develop any recording processes or use any weird FX during this period?

SJ: As Skullflower I would say not. Apart from our limitations… and I think we did get slightly more professional as we went along… we did conventional eight track recording in a fairly standard way. We used to play live [in the studio]. Sometimes Matthew would turn up with a bassline that he had imagined at home; he would play it and we’d all join in – if it worked out we’d gesture to Ian to record it, and that was it. It was usually the first take that was recorded. The only thing we’d do afterwards would be that Matthew would record some vocals over the top of it. We didn’t do any electronic fuckery with instruments particularly. Some stuff at some point was looped. But most of the time it’s us playing live as a quartet, recorded live in one take, with Matthew doing the vocals later. It was an instant composition thing. That was just the way it happened. There was never any talk about what we were going to do. We would mostly just plug in and play and through serendipity all those tracks manifested themselves.

Something that often comes up with bands who play music where the emphasis is not on the lyrics or the singer, is that they often find it a pain to name songs. I was just wondering what happened in Skullflower. I can see one’s called ‘Solar Anus’, which is a Georges Bataille reference, right?

SJ: Yeah. Occasionally Matthew would produce titles like that one from stuff that he had been reading. But the titles were definitely added afterwards. We recorded the tracks, and this would become a cassette of rough mixes of material. Then, when we were trying to work out whether we liked any of it or not, we would sometimes give them random song titles or names so we could identify them. ‘Solar Anus’ was definitely a “proper” song title that Matthew came up with for that album, but some of the titles were instant compositions as much as the music was. We would listen back to the music in the studio and free associate or pick something to do with whatever we were particularly obsessed with at the time. ‘Grub Song’ on the first EP came about because I’d been in LA working on some crappy teen zombie movie as a publicity assistant; I’d been to Mexico and brought back some mescal, and we were sitting round bullshitting in the studio about eating the grubs at the bottom of the bottles, so it became a song title.

What was it about being in Skullflower that made you never want to play the guitar again?

SJ: [laughs] I don’t know. I just decided, “Fuck it. I’ve had enough.” I was so pissed off when I left Skullflower. And then not long after I bumped into William Bennett in Vinyl Experience on Hanway Street. I hadn’t seen him for about five years. He said, “I’m thinking of starting Whitehouse again. Do you want to be in it?” I said, “Oh yeah. Sure!” And that provided me with a good reason not to play guitar. I hadn’t picked up my guitar in three years when I met Tony Irving, the Ascension drummer. He literally bullied me into coming down to practice for that band. And he really did bully me into doing it. I really wasn’t into it. I kept on saying, “No. No. No. I don’t want to do no rock & roll shit man.” [laughs] In the end I took my guitar down and it was still in the same case where I’d left it after Skullflower, not tuned or anything. Then I played along with him and I was, “Wow, this is great…”

Was it Skullflower that kickstarted your interest in free music, or was that because of something else?

SJ: That was happening during Skullflower, but it wasn’t Skullflower that kickstarted it. It ran parallel. Earlier in the 80s and even back as far as the 70s I’d been buying things like Fred Frith’s Guitar Solos and I’d been getting stuff on Incus records by people like Derek Bailey. There was one particular album that made me want to play in a certain way. The first Massacre album, Killing Time, was essentially the rock music I wanted to make. I just used to play that all the time, bonged out. There was one particular track on the first side with this insane bit of feedback, and I just used to think, “This is the greatest thing ever. If only all rock music – or improvised rock music – could be like this.” And the way that Frith approached his instrument with Massacre had really left a lasting impression on me.

And as Skullflower went on I wanted to [do something else]. I’d been listening to a lot of free jazz and I had less time for structured rock music. Well, for playing it anyway. I was still a massive fan of the Butthole Surfers and Sonic Youth and what have you in the late 80s, but more and more it was impinging upon my consciousness that there was more to be done with the guitar than playing the way I had been playing it. I have thought about how this affected Skullflower, and I can’t come to a decision, I don’t know how much of a detrimental effect this had on me in my later days with with the group. I haven’t been able to compute it; whether my subconscious desire to be doing something slightly different was manifesting itself in dissatisfaction at what we were playing. I also thought that we were going to keep on playing the same thing forever, unless we made a conscious effort to become more professional or something like that. In retrospect I might say that I felt I was progressing, perhaps… some idiot notion that one shouldn’t keep on doing the same thing all the time…

How important was the use of narcotics in Skullflower?

SJ: [laughs] We liked our crappy blotter acid. There was a lot of low quality acid about. Matthew, Stuart and I liked to drop acid at our recording sessions; Gary absolutely didn’t. He didn’t take any kind of substance at all that I can remember. But we liked to bong load it, and we liked cheap blotter acid. I guess we imbibed reasonably, but not so much where we couldn’t stand up and play. And that acid wasn’t very strong, it just gave you a good, hefty paranoid buzz, which no doubt contributed considerably to how we constructed our music. I don’t know what it was like for Gary to be trapped in a studio for eight hours with three psychopaths tripping balls. [laughs] Rather him than me.

feature continues after sleeve art

Were Skullflower a heroin band?

SJ: No. In the very early 80s there’d been that flirtation caused by the influx of cheap skag. It was happening around the time I moved to London in early 83. But no, no, no, definitely not. Not in any way. We liked to smoke dope and drop acid. But even then, once I started breeding, I stopped doing because it freaked me out. One night a friend had been round and we’d done some acid – my kid wasn’t even a year old and the wife was asleep, I went up to check on him and I realised that it was fucked up, it was ridiculous, you can’t be tripping balls and changing nappies at the same time. So I knocked it on the head, it had phased out before I left Skullflower even.

So what can you tell me about Xaman? If I make it right, when you listen to these CDs back to back you can hear that something has changed by the time Xaman comes out, even if it’s only that something has changed in the way that you are recorded or produced. It’s certainly Skullflower’s most “rock” album. How did that happen? Did you record in a better studio?

SJ: No. Everything was recorded in the same place. It’s interesting… one of those tracks, possibly ‘Wave’, we did as a day time recording with a different engineer, Joe [Steele] instead of Ian [McKay], and perhaps it was his way of mixing that made the instruments clearer. There was always a slight friction, because Matthew and possibly Gary as well liked the murkiness of the early stuff, and I always felt that I wanted the instruments to be clearer in the mix. ‘Wave’ is something that we’d been playing since our first session and was written when Alex Binnie was in on bass. And that was one track that we decided that we would record “properly” for the album. So yeah, that was a deliberate act of recording. We set out to play it for as long as we could until we all collapsed on the ground, essentially. 27 minutes was as long as we could manage before Stuart, the drummer, just collapsed.

Maybe it’s because we’d stopped tripping balls… who knows? Maybe that was the music we made after sobering up. It is a noticeably different sounding recording, it has a different feel to it, it hangs together well. It was made from three sessions with the old song in the middle. We were down to a trio, Matthew had stopped singing and Stuart had taken over on vocals, so when you deconstruct it like that, there were a lot of different forces at play to make that album. But then again you could just say that it’s a logical progression. You have to develop. If we’d made three albums that just sounded like Form Destroyer, I don’t know if we would have been as enthused about it as we were. Man, you’ve got to move on, as Malcolm Mooney said.

I was 19 at the time when Xaman came out, and if I had heard it back then I would have loved it. It would have been my favourite album of that year. Were you still that anti-publicity at this point?

SJ: Well, I wasn’t, and this was another straw on the camel’s back. I used to send out review copies and Matthew really didn’t want to. I remember talking to him about this constantly and saying, “If we want people to buy this album then we have to get it reviewed. We can’t just keep on taking five copies a time down to Vinyl Experience and having people say how cool it is. If we want to keep on putting out records we need people to pay attention and say how great we are and that people actually need to own this record.” And grudgingly eventually this was agreed on, which is why we eventually agreed to do an interview with a fanzine with a readership of about five people when Matthew and I were at the height of our psychosis. [laughs]

That interview [included in the CD sleeve notes] is hilarious. I almost feel sorry for the interviewer. True enough his questions are a bit shit, but the levels of balefulness he gets in return…

SJ: Oh, he was a prat though! Our responses were sent in by post, neither Matthew or I saw each other’s responses. So in a way it makes it more entertaining that it ends up like that without us even colluding. That guy’s fanzine was terrible. I guess you could say he had the best will in the world, but it didn’t work on us because we weren’t full of good will at the time. I guess all of this stuff helped to spread word about the band a little bit, but things moved so slowly then. I was friends with Savage Pencil [Edwin Pouncey] and he reviewed Form Destroyer in the NME. Forced Exposure loved us from the get go. It was Edwin who suggested that I start a label. I’d done a festival for Shock Xpress and for once actually made a profit. I said to Edwin, “What am I going to do with all this money?” And he said, “Why not start a label and call it Shock?” Serendipity. So much of this stuff didn’t happen with any intention.

And you’ve revived Shock now to put out these Skullflower reissues, haven’t you?

SJ: Yeah. Originally it was revived to do the Skullflower CDs and I’ve been doing a bunch of new stuff myself as well after going through my archives. I started playing music again, this time actually sticking to my original post Skullflower intentions and not playing guitar. I’ve been friends with Steve Pittis at Dirter for years and he always used to say, “What are you going to do with all that Skullflower stuff?” And I was like, “Just fuck off and don’t ask me about it again! I won’t put it out unless I can work with Matthew, and I just don’t see him speaking to me. I can’t imagine that either of us would speak to the other one. It’s been so long now I can’t see it happening.” And then out of the blue I got an email from Matthew saying, “Just to let you know Justin from Cold Spring wants to put out a compilation of early Skullflower stuff, what do you think about these tracks?” And I thought, “Well, this is a gift from the gods isn’t it?”

So I emailed him back and said, “How about we do the whole fucking lot, including all the crap that’s sitting round in my basement, and we can do it properly? I can do it with Steve because he’s OCD like I am. And then we’ll just sit there agonising over it for ages, just so we know we’ll get it right.” And he said fine, so we decided to revive Shock to do it. It took 18 months to get it right, and during that time, coincidentally I ended up buying a lot of electronic equipment, laying it all out on the floor and ended up doing a lot of noodling around on synths and doing a lot of electronic recordings on synths. Going through the Skullflower tapes made me go through my stuff from the early 80s. So the label is now actually going again.

What stuff of yours is coming out on your label?

SJ: I’ve got a solo 12” out on Shock. It’s still sort of instant composition using two sequencers and a bunch of synths. It might take me a full day to find some noises that I like, because I like working with analogue synths, and obviously there are no presets on them. It’s easy to get sidetracked into just entertaining yourself. I’m doing quite a lot of home recording. I’ve got another 12” that I’m just waiting for test pressings of, and I’ve already got an album’s worth of stuff ready to go for next year. I didn’t think I’d ever feel confident enough to release solo material [again]. But your attitude changes over the years… I’ve been using a ton of synths, my favourite two are an an MFB Urzwerg Pro sequencer and an MFB Dominion X SED. I’m using a Moog Minitaur bass synth, a Waldorf Blofeld, an Access Virus TI and a Dave Smith Mono Evolver PE. I’ll use the sequencer to programme up to two synths and manipulate them live with rhythms and then generally dump another one on top of that. I don’t use a computer or editing software. I play it live, or as live as is possible. And again, whatever happens is what happens.

Where can people find out about these releases on the web?

SJ: [laughs] There isn’t anywhere! I don’t have any kind of web presence…

Well how do people buy it then?

SJ: Well, Cargo are distributing my stuff and I’m doing it mail order via Shock (shockrecs@gmail.com), but yeah, it’s kind of a struggle not having a web presence and I’m going to have to drag myself into the 21st century. Everyone tells me it’s what I need to do, and that I’m a fool for not doing it. Boomkat, Norman and Forced Exposure have the 12” as well…

Going back through all this material for the Skullflower reissues, did it give you any fresh insight into what you were doing, or did it remind you things you’d forgotten about?

SJ: Yeah. Absolutely. Weirdly enough, I had a 99.9% positive reaction to hearing it all again. I think I had become quite scared of listening to the tapes over the intervening years. I was so pissed off by the time I left Skullflower [and] Matthew and I didn’t part on particularly good terms… but dragging those tapes out of the basement… I always thought those tapes in the basement would have some prime Skullflower on them, and they were wildly exciting to listen to. I really did enjoy it. There were so many times listening to them when I would think, “Jesus Christ! I can’t believe we were doing this… What the fuck was going through our heads when we were recording it? This stuff is unbelievable.” It made me realise that we were doing something right when we were recording this stuff, even if we weren’t fully aware of what it was while we were doing it. And amazingly enough, Matthew and I agreed on everything. Everything about doing them apart from the horrific 18 month production time, was an incredibly positive experience, which I just wouldn’t have thought would have been possible.