The Olympics feel like a long time ago. Stratford is arguably now regarded primarily as the site of a future stadium for West Ham United and of Westfield, a mall which has embedded itself into the national consciousness as a synonym for spending through the recession. Bradley Wiggins no longer heads up the peloton of UK cycling, and Mo Farah’s recent press has centred on his links with a controversial coach rather than his athletic proficiency. More generally, Britain’s sporting focus has switched back to the underwhelming showings of its national football teams, and there are profound doubts about the success of the Games’ so-called ‘legacy’.

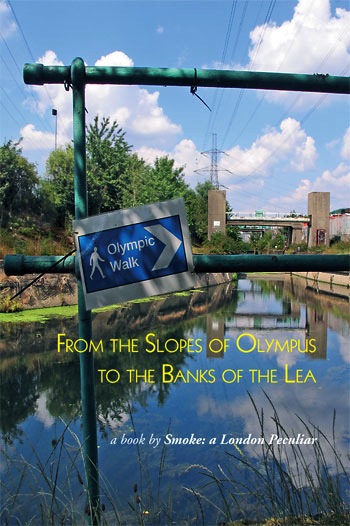

Because of this, there’s something curiously nostalgic about reading Smoke: a London Peculiar’s new book From the Slopes of Olympus to the Banks of the Lea. Assembled by Quietus regular Jude Rogers and fellow scribbler Matt Haynes, the work is a compendium of writings taking a slanted look at what happened in East London during and in the run-up to July and August 2012. The emphasis is not on the events themselves but on both the social shifts they occasioned and on what took place peripherally to the sport in Stratford and other London locations such as Greenwich. As such, what the reader is presented with is a window which opens onto the political landscape of last year: the security paranoia encapsulated in the SAM missiles on Blackheath, the debates around austerity politics which Danny Boyle’s social democratic son et lumiere contributed significantly to, the Londoners shifted away from the area in which they were born and raised under the aegis of a Mayor fighting the corner of a new aristo-plutocracy.

Rogers and Haynes started Smoke up in 2003 as ‘a love-letter to London, to the wet neon flicker of late night pavements, electric with endless possibility, and the soft dishevelled beauty of the city’s dawn’. The magazine had clear consonances with the psychogeography of Iain Sinclair, which, after years of stirring beneath the cultural plimsoll line, achieved real visibility with the publication of the Hackney-residing author’s London Orbital in 2002. Since then, psychogeography has proliferated to the point at which the word has lost much of its currency: nowadays, every writer and artist in the city seems to have something to say about the ley-lines of Bermondsey, the ghost stations of the Underground and the broad magic of the urban everyday. It’s almost hard to believe that the movement – if that’s the best term – arose out of the radical thought of late-sixties Situationism, such is the degree to which its efforts to substantially alter the way in which the city and its processes are perceived has given way to whimsy.

This book is, to a degree, guilty of not noticing the gradual transformation of the psychogeographical worldview into an off-the-peg way of seeming interesting. Its primary tropes include the chanced-upon conversation, the low-level gesture of subversion and the inadvertent surrealism of the metropolis, all of which are familiar to seasoned readers of Sinclair and those writing in his shadow. That’s not to say that most of what has been drawn together isn’t moving or amusing, just that it comes over as a little belated. Many of the things it covers would have worked better had London hosted the Olympics in 1996 or 2000. That being said, there is always something to be said about London.

One of the main ideas that implicitly carries this book regards a city in a state of perpetual flux, an idea that also came to the fore in Julien Temple’s film London – The Modern Babylon, another piece which used the Olympic year as a crux for its investigations of the genius loci. Rogers and Haynes have done well to represent the dynamism of a section of Europe’s largest conurbation, and to at least point towards the political and economic processes which underpin this.

What is captured best, though, is the gradual shift in the capital’s attitude towards the Games that took place as they progressed. Up until the bombastic first night, the national mood had contained a large degree of scepticism, and many on the left were concerned that the Olympics were being used as a distraction by a government pushing through public sector cuts on a huge scale. Once Team GB started to win medals, however, a number of those who had previously been grumbling began to be captivated both by the energy which emanated from Stratford and the way in which Britain’s successes mirrored the country’s increasing diversity: Farah in particular was embraced as a representative of the country’s immigrant population, a short answer to the idiocies of UKIP and the BNP. From the Slopes of Olympus to the Banks of the Lea uses a largely chronological structure to index the warming up that occurred during the competition, and both editors – who contribute a good deal of the material here – are unashamed to imply that they were drawn in by the spectacle.

One wonders, however, if the Olympics has been given a retrospective free pass thanks to the successes of Farah, Wiggins, Jessica Ennis and Nicola Adams. The fact that the medallists were drawn from a relatively diverse spread of economic and ethnic backgrounds has possibly papered over the fact that the Games did obscure widening inequalities under the Coalition. Since then, things have only got worse. A year down the line, London is a site of latent – and sometimes not-so-latent – hostility and anxiety, as the far right march on Whitehall and rent prices continue to rocket with no obvious sign that any of the major parties possess the political will to do anything about it. The regeneration of Stratford and its environs in the years leading towards 2012, captured very well in the book, involved developers riding roughshod over communities in East London; what we need to remember is that this is still happening, and very probably on a greater scale.

From the Slopes of Olympus to the Banks of the Lea is available now, from the Smoke website