Both July and August were all about sub-bass frequencies: thick, overwhelming pulses of viscera-vibrating sound that temporarily turn the senses to jelly. Similarly intense counterpart presences to the hottest summer we had in years, they rumbled through the backdrop of the last couple of months, which were a total blur of musical and music-related activity (one excuse, again perhaps, for this edition of Hyperspecific arriving as late as usual):

Hours spent hugging sound systems at St. Paul’s Carnival in Bristol at the beginning of July, a joyous reaffirmation of the importance of music as physical presence (made all the more crucial by the relative lack of such experiences in London’s current rather sparse selection of small, high-powered club spaces). Peverelist cutting into jungle for the final half-hour of the final set at Freerotation festival, a moment of collective dancefloor shock and awe that was still being discussed in hushed tones for weeks afterward. A subsequent week spent in Bristol trading thoughts and ideas with the city’s crop of current low-end practitioners (Pev included) for a lengthy feature in The Wire, serving again as a reminder that electronic music – and dance music in particular – is about more than passive absorption, it’s about engagement, in all senses of the word. Ishan Sound dubplate firepower and ‘Clash Of The Titans’ in the basement of the Exchange. Kowton’s ‘TFB’ still going off like "a plane landing in the club" (his words, not mine).

Playing a Chris Watson recording of Lindisfarne seagulls on Plastic People’s sound system and marveling at its sheer richness of sound. Revisiting Dizzee’s early output – which for some impossible-to-place reason has always left me slightly cold compared to the work of contemporaries like Trim, Ruff Sqwad and Wiley – thanks to Dan Hancox’s thoroughly recommended e-book Stand Up Tall: Dizzee Rascal & The Birth Of Grime. The romantic atmospheres conjured up by Galcher Lustwerk in his 100% Galcher mix of sensuous deep house and abstract, melody-saturated meanderings. A surprisingly punchy airing of Rhythm & Sound’s With The Artists on a pair of daisy-chained Minirigs in a field near Dartmoor. Surprise rewinds on a Thomas Bangalter classic versus the mind-numbing ubiquity of ‘Get Lucky’ as it pumped from every construction site, corner shop and market stall radio, every car window, every office stereo, every shitty set of leaky earbud headphones on the tube.

Some of the music that provided the summer’s backdrop has found its way into a new mix I’ve just recorded for the ongoing mix series by Colony, the London-based promoters with whom we’ve teamed up to host a Colony vs. The Quietus party at the end of this month (details of that here). It features recent and new/unreleased music from the people we’ve booked to play – Mark Fell’s Sensate Focus, Beneath (whose killer and brand new ‘Bored 1’ opens the mix in depth-charged grime style), TVO and Dom Butler of Factory Floor – as well as a host of exciting new music from the likes of Emptyset, Livity Sound, Production Unit, Katie Gately and Visionist (the latter two of whom appear in this month’s column). You can listen and download via the embed below.

Perhaps as a reaction to a rather dance-centric summertime, this month’s Hyperspecific is pretty shy on club-focused sounds, instead opting for more exploratory, in-between-zones material. Read on for virtuosic voice processing, the sound of alien colonisation in action, a long-distance eski affair and more lovingly packaged vinyl editions.

Visionist – I’m Fine

(Lit City Trax)

Rabit – Sun Showers

(Diskotopia)

NA – Xtreme Tremble

(Fade To Mind)

As if to emphasise its current position as a largely internet-disseminated genre, the grime community exploded into action last week when an opening gambit from Bow producer Bless Beats – a ‘war dub’, uploaded to Soundcloud – escalated into full-scale producer-on-producer warfare. What seemed like every beatmaker in the game joined in, from veterans to near-unknowns, each uploading their own war dubs in a massive game of global internet one-upmanship that swiftly became too large and convoluted to keep proper track of. I’ve admittedly only listened to a handful of the scores of brief war dub tracks that have been uploaded over the last few days, which vary from pretty great to sounding more like hastily knocked out sketches that could have used a little more work. (In terms of entertainment alone I particularly enjoyed a witty back-and-forth exchange of battle cries between Londoner Visionist and Bristol duo Kahn and Neek). There’s a nice collection of a few of the best over at FACT.

But aside even from its pleasing injection of a blast of energy into grime – a brief reigniting of the sort of rivalry that’s driven the UK dance music evolutionary arms race over the years – as a phenomenon it’s served to hammer home the broad, global nature of the genre in 2013. Having survived a series of dramatic plot-twists across its now teenage lifespan that’d be enough to sink most nascent styles – an explosion into the public eye off the back of Boy In Da Corner, pop flirtations and diversions into cookie-cutter electro-house, a several-year-long slump in listener interest and a recent, gradual return to (sort of) vogue – grime’s in much better shape than it has any right to be. Even more so when compared to the majority of other UK-borne dance styles, which tend to lapse into staid predictability by this point in their lives. By contrast, grime at the moment is more varied and volatile than it’s ever been – covering a wide tempo range, chewing up bits of other genres with pleasingly omnivorous glee and arriving from outposts all across the globe – making it difficult to pin down quite where its borders lie.

And I’m not sure if there’s a better example of those hazy borderland territories than the current rapid exchange of frosty sound matter between the States and the UK. The shared territory currently occupied by UK residents like Logos and Visionist and Stateside producers including Rabit, Fatima Al Qadiri and Nguzunguzu suggests the honeymoon period of a transatlantic grime romance. (Much as he might vainly try to position himself as ever the outsider-auteur, UK citizen living abroad Zomby is part of this exchange too – and, in fact, can probably take some credit as an influence, given that he was doing something similar in around 2009.) If, indeed, you can get away with calling it grime: not quite brittle and bristly enough to inhabit many of the dancefloors typically associated with the genre, but absolutely drenched in stark, minimalist and deliciously chilly sonic trickery, the music emerging from that axis at the moment seems to inhabit some other place entirely. When I wrote about Al Qadiri’s Desert Strike EP at the tail end of last year I mentioned "yoga music for an ashram in Second Life", and while there’s an intriguingly new-agey, meditative aspect to these producers’ work, there’s also a distinct air of menace. Street music, perhaps, to soundtrack the darkened corners and back alleys of the pristine virtual cityscapes conjured up by recent James Ferraro and Daniel Lopatin releases.

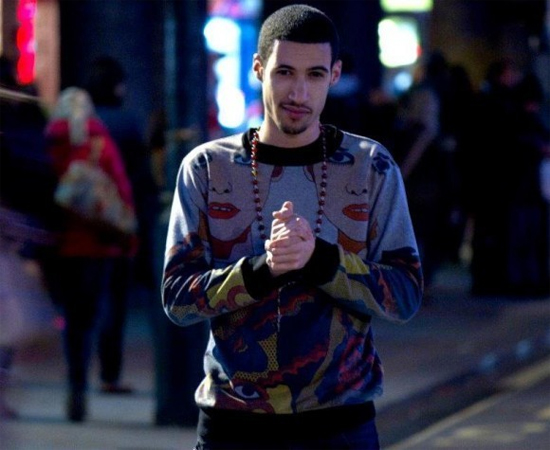

Indeed, the wordless vocal constructions of Visionist’s new I’m Fine EP, near choral in their grace and grandeur, are distinctly reminiscent of the intricately composed zones-without-people of Lopatin’s upcoming R Plus Seven album – a telling bit of convergent evolution. The EP itself contains six tracks cast in delicate miniature, including a collaborative work with Al Qadiri, and is, frankly, superb. Louis Carnell (pictured, top) is a shapeshifter by trade – with his output to date including dessicated drum machine tracks, murky-as-fuck recent banger ‘Snakes’ and plenty of impact-led club fare – and I’m Fine represents a temporary step away from dancefloor concerns and wholly into a stiflingly melancholy virtual urban world. For just over fifteen minutes, fractured drum machine patterns ascend Escher-like ladders to nowhere, melodies glint invitingly like neon signs through mist, and vivisected, pitch-shifted voices fret obsessively over tiny thoughts. Given its sparseness and sub-zero temperature, the obvious touchstone for Carnell’s work (and most of his contemporaries) is eskibeat – that clutch of infinitely influential early Wiley productions. But beyond the obvious surface influence it’s quite distant from those now decade-old tracks. Here, melodic elements are so drowned in effects that they become hazy and translucent gestures – less the brittle icicles hanging off the staircases of Wiley beats like ‘Ice Rink’, more the fog of breath on a freezing cold tower block window.

The same is true of Houston resident Rabit, whose new Sun Showers EP imagines grime as incrementally reshuffling four-dimensional sound sculpture, more exhibition curiosity than functional club form. Far from the heat implied by the title, it sounds as though each component has been dunked in liquid nitrogen. Compositionally, meanwhile, these four tracks don’t really travel anywhere, more create a space and loiter there stubbornly: the title track’s pinprick melodies and squared-off sub-bass gusts suggest Actress’ R.I.P album transposed into hi-def, while the reverb-laden ’40 Below’ sends smashing windows and phaser zaps echoing outward into empty cathedral space. It’s unsettlingly empty-sounding, a sensation heightened by the sheer disconnect between its ostensible origins in communal dance music and its profoundly isolated reality. To be fair, though, in the right context ‘Levels’ could send dancefloors into a delirium of delighted confusion, its dry twig-snap funk and rewinds-as-percussion sitting somewhere between recent Pearson Sound and A Made Up Sound and the drum-stacked DJ tools of Helix.

Xtreme Tremble, by Nguzunguzu’s Daniel Pineda under the guise of NA, sits in the same space. It contains three tracks of spring-loaded, bolshy club music, driven along by cheese-wire handclaps and pirouetting sino-grime-esque melodic flourishes. Trap’s ubiquitous rolling boom-kicks find their way into the mix too, undulating throughout ‘Flute Gasp’ with an intensely threatening swagger, as if something’s about to kick off at any time. (In that manner it’s also reminiscent of D1’s precocious drum machine-led dubstep productions, which did an impressive job of anticipating what was to follow in UK club music.) Like the others I’ve discussed here, despite its air of aggressiveness it’s marked out by its beguilingly freaky spatial properties, where swathes of reverb and delay rebound through environments that are unsettled and prone to rapid flux. Is it grime? Does it even matter? Your guess is as good as mine, but it’s certainly not not-grime, and if these hybridisations continue to pump energy and inspiration into the genre from elsewhere, then so much the better.

Helm – Silencer

(PAN/Alter)

Rashad Becker – Traditional Music Of Notional Species Vol. 1

(PAN)

If you’ve been reading Hyperspecific for a while you’ll know that one of its predominant running themes is information overload. Like a lot of people, I have a fraught relationship with the internet that extends far beyond my initial unwillingness to relent and get a smartphone (which eventually happened earlier this year) because I didn’t want to feel umbilically connected to the digital world all the time. On the one hand, there’s a lot of great music that wouldn’t exist were it not for the net, and digital musical distribution makes both my job and my hobby (for what it’s worth drawing the distinction) far easier. On the other, consuming music while you’re staring at a screen doing something else – answering emails, most likely – is tedious and unrewarding in the extreme (and does feel like consuming). And while the internet has certainly allowed great gyres of uninteresting material to pass into common circulation and clog the inbox like so much partially digested plant matter, what’s actually proving confounding above all else is an overwhelming quantity of good music. From every angle we’re informed of the existence of new and ‘essential’ 12"s, albums, unearthed lost gems, reissued classics, entire new genres invented by a bedroom producer somewhere in Venezuela, TIP! – all worthy of attention in their own right. How is anyone supposed to sift through that amount of material without sacrificing their sanity, their social life or their love of recorded sound? The answer, of course, is that they’re not – but that doesn’t stop you as a listener from feeling a vague sense of unease that there’s all this great music you’ll never have the time to experience. It’s rather like that sensation of walking into a massive bookshop and feeling that twinge of guilt as you shuffle through all the novels you’d like to read or are supposed to have read, and know you’ll never manage to get through even one per cent of them.

All of which is a rather long-winded preamble to saying that therein lies the value of a good record label. Although the advent of platforms like Soundcloud and Bandcamp has made it easier than ever for artists to self-distribute without an interim figure (entirely a good thing), it remains a unique pleasure to follow a label you trust religiously and allow its curator’s tastes to guide you to new places. As much as anything else it imposes its own narrative upon your listening, which has (for me at least and I’ll wager many others) never felt more important at a time when the pure music itself can be accessed totally free of back story. Which is why certain labels go through phases of cropping up repeatedly in this column – Hessle Audio, for example, or more recently Morphosis’ Morphine – they’re guides towards music I might not have come across otherwise.

The same goes for PAN, which has attracted a perhaps surprising amount of attention across the past 18 months considering the often challenging nature of its output. (Admittedly, the amplification effect of self-curated social networks – which bear little resemblance to the interests of a real life populace – can easily make even modest interest in an artist seem like everyone’s hyping them.) But there’s a simple enough reason for the amount of love given to Bill Kouligas’ label. It’s well presented, with releases each coming in their own printed polyvinyl sleeves that make them irresistible to those (like me) with a magpie-like attraction to prettily packaged records – but above all it’s well curated. By mixing up freeform experiments in noise, psychoacoustics and improvisation with more easily accessible forays into dance, ambient and drone, its output possesses a distinct character but remains varied enough to make each new release as intriguing as the last. Having taken most of the first half of this year off to hold the PAN ACT festival in New York, the label’s release schedule has abruptly fired up in earnest, with a salvo of material just released and lots more imminent. Chief among them have been three additions to its great 12" series (which kicked off in fine form in last year with SND/NHK, Lee Gamble and Heatsick), from Regis and Russell Haswell’s Concrete Fence project, Black Sites, the Hamburg duo of Helena Hauff and F#X, and London noise artist and sound manipulator Helm – the latter of which has been on continual rotation these past few weeks.

Because I don’t make electronic music, I’m still more often than not pleasantly clueless as to the actual technical approaches that went into its creation. As Helm, much of Luke Younger’s practise involves taking acoustic sound sources and using various processes to twist them out of all recognition. Beyond that brief summary, I have very little clue as to the intricacies of what he does in order to create such strange, earthy yet urban music, which only serves to heighten its appeal. Like last year’s unsettling Impossible Symmetry album, Silencer‘s palette of background electrical hum, clanks and shrieks, metallic echoes, dripping water and ambient sound suggest that he’s cracked the surface of the city and inserted microphones right into active infrastructure, building up an imaginary perspective of a city’s activity from the unseen underground upward. It’s oppressive and vaguely seedy stuff, and as with its predecessor I can’t help but hear facets of London (and our current grim sociopolitical situation) encoded within it, but equally there’s a strangely grandiose and triumphant air to parts of Silencer that Impossibly Symmetry lacked: the huge, hard-edged drums that propel the title track along, for example, or the towering brass section drone that rises stately from the wreckage of ‘Mirrored Palms’.

Another recent PAN release, even more impossible to decipher, feels like a low-key revelation. It’s actually been out for a couple of months now, but I’ve been intentionally holding off writing anything about Traditional Music Of Notional Species Vol. 1 – the debut album by Rashad Becker, the renowned Berlin mastering engineer whose name is probably etched into a fair proportion of the records you own – until I’ve had the time to fully digest and internalise it. As befits a musician whose day job requires impeccable attention to textural and spatial detail, the first thing that hits you about Traditional Music Of Notional Species is its virtuosic sound design and depth of field. Its tracks – tightly meshed assemblies of squelching electronic tones, synthetic brass and reedy drones, swampy and mossy masses of background noise – are intensely humid and absolutely loaded with detail, but never once sacrifice clarity; hitting play is like passing through a portal into another space entirely, where the calls of unseen and unimaginable creatures mingle with a haze of ambient environmental sound.

Becker’s is among the most fleshy and organic-sounding electronic music I’ve come across. Its rhythms don’t so much beat as pump and lurch in weird time, rippling like soft tissues as blood pulses through them, while its lead melodic motifs – slippery, spaghetti-like squiggling tones – might be synthesised but blur the lines, sounding played from horns and pipes carved from bone, sinew and skin. But whatever they are, these are decidedly other forms of life – in its skin-prickling heat, humidity and and unsettling unfamiliarity, listening to Becker’s sound worlds here feels akin to being dropped into the middle of an alien hive on a distant planet somewhere, where everything is slimy, moving and alive. The title, then, is perfect: these pieces play like archaic folk forms from some distant imaginary civilisation, wrung from unknown instruments by unknown players. It’s a jarring listen at times but a spectacular one, and as a demonstration of the potential of electronic music to subvert the laws of our world and envisage a completely new one, it’s unparalleled, making it one of PAN’s best releases to date. Volume 2, if indeed there is one, can’t arrive soon enough.

Katie Gately – Katie Gately

(Public Information)

And while we’re on the subject of trips into unfamiliar territory… Vocal science has long been a central trait of dance music, so much so that violent electronic manipulations of the human voice have become emblematic of certain styles: the drug-addled, manic and paranoid timestretched voices of hardcore and jungle, for example, or the delicately sliced vocal shards that dance weightless through garage and two-step. Equally, the ubiquity of autotune in recent years has represented an even more overt and mainstream merging of human voice and machine. Los Angeles-based Katie Gately, however – a recent signing to London’s Public Information label who has apparently only been writing songs for a year or so – comes from an academic background in sound design, and her debut mini-album contains six examples of exquisitely weird, vocally vivisected songwriting.

One obvious comparison that’ll be made both here and elsewhere is with Holly Herndon, another academic composer who attacks her own breath and voice with heavy digital processing and whose Movement album was a favourite from last year. And while there are certainly parallels between their work, where Movement (save one track, ‘Fade’) eschewed song structure, Gately’s music is very different, turning kindred techniques towards frostbitten but playful forms of pop. Even just in terms of composition and technical skill alone it’s a formidable debut, but it’s also possessed of an unusually strong personality for a first release – in a way that reminds me slightly of Becker’s album, it establishes and inhabits its own separate world for the duration. Opener ‘Ice’ set out the album’s store, its jagged hi-frequency icicles piercing through chilly background ambience in a manner that brings to mind the extreme noise/techno percolations of Metasplice. The five tracks that follow find Gately’s voice wandering through this hazardous environment: drifting freely through space on ‘Last Day’ ("I awoke from a little hole underneath the earth") while tectonic plates grind deep below; twisted into uneasy, wordless harmonic alignments in ‘Stings’ and blasted into tortured shreds on ‘Dead Referee’. Closer ‘Stems’ is a highlight, for its jarring presentation of pastoral imagery – "Nightingale, in a little hollow" – in a voice so brutally wracked with effects that its edges shimmer like a fresh razorblade. With another new release on Blue Tapes upcoming, it’ll be exciting to see the direction that Gately takes this aesthetic in future.

Hyperspecific returns in October with another selection of new electronic music for heads and feet