"You use ostrich tuning? Oh my God!” Lou Reed’s face breaks into a smile and emits a chuckle as his right hand slaps his chest before exclaiming, "How fabulous!”

It’s been all too easy to take Lou Reed for granted but to make mention of the tuning used on many of the seminal recordings made by The Velvet Underground is to acknowledge one of the many facets of his genius. A point of interest to many sonic architects, it’s a process whereby all the guitar strings are tuned to a single note to create a rich, fat, ringing sound that can’t be achieved on conventional tuning. It also means that strings can be left open to give the added dimensions of drones to produce a more panoramic sound. Producer Mike Leander certainly knew the score when creating the incredible wall of sound achieved on Gary Glitter’s ‘Rock & Roll Parts 1 and 2′ and the tuning was used to devastating effect on My Bloody Valentine’s breakthrough, ‘You Made Me Realise’.

And right now Lou Reed is giving The Quietus some tips on this tuning style.

"You tune to D?” asks Reed. "I’m pretty certain that it was tuned to B. The strings will stay in tune longer."

We’re talking in the subterranean confines of Trident Studios in the heart of London’s Soho. A fitting location given that this is where Reed recorded 1972’s Transformer with the aid of uber-fan David Bowie and his right hand man, guitarist Mick Ronson.

To be precise, the PR informs The Quietus that interview will be taking place on pretty much the very spot were Reed recorded his vocals for that album. Over 40 years on, Transformer sounds as fresh and daring as ever. A paean to New York City’s nightlife and the colourful characters that emerge in the afterhours demimonde of the Big Apple, the album alerted the wider world of the existence of Reed and his incredible talents as a singer, songwriter and performer. His skills as a lyricist – an observer with an eye detail that utilizes the direct and hard metre of Raymond Chandler – cast a non-judgmental eye on an underworld that crashed through the essentially heterosexual confines of the so-called period of free love to create a polysexual universe that was at once seductive and alluring. Coupled with Reed’s innate songwriting ability, Transformer is an album that continued the work Reed started with The Velvet Underground and one that emphatically proved that rock & roll could also be art.

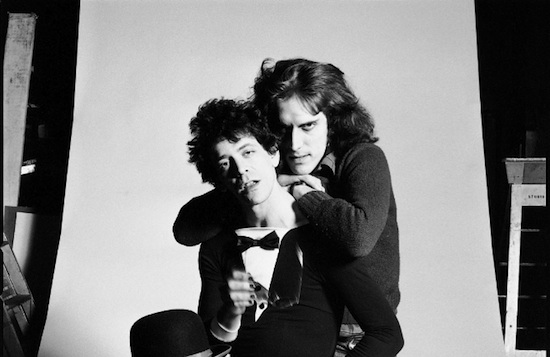

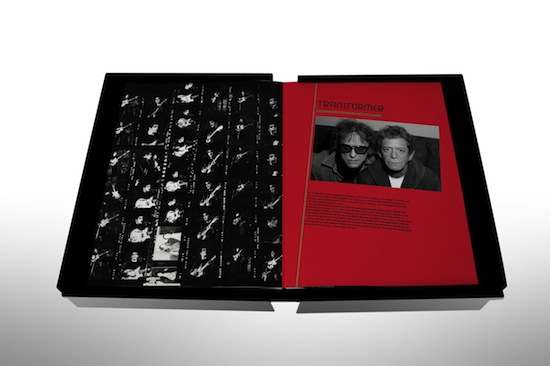

Crucial to the standing and enduring appeal of Transformer is the imagery of Mick Rock. As the only photographer present at Reed’s debut British concert at the King’s Cross Cinema (now known as The Scala) on July 14 1972, Rock captured the moment that crystalised the image of Reed in those heady and intoxicating days of lipstick, powder and paint. There it is – a study in monochrome, an unintentional pose frozen forever, the shot that finally makes the cover of Transformer is a thing of glorious wonder. His face a deathly white with eyes highlighted by dark mascara and eyeliner, it’s as if Reed is emerging from the night to tempt us into a world of illicit sexual delights, chemical thrills and an attitude that dares you to forget everything you think you know about convention, morality and mores. And by picking up that album sleeve, carefully removing the vinyl from the inner sleeve and placing it on your turntable and dropping the needle, you’re part of the way there. By the time you’re flipping it back over from the end of side two back to ‘Vicious’, the realisation creeps in that this is a world you don’t want to leave and hope that the sun never rises again. Or at least if it does, you’re going to sleep right through it. Looking at the contact sheet from this historic session, this is the image that stands out from the other shots and it’s clear to see why this is the one chosen for the album cover.

So successful was this marriage of the audio and visual that it’s little wonder that Reed and Rock struck up a personal and professional friendship that continues to this very day. Alongside the enduring iconography caught by Rock of David Bowie in all his various guises and Iggy And The Stooges’ storming of The Scala in 1973 among many others – not for nothing is the photographer known as ‘The Man Who Shot The 70s’ – Rock was there throughout that decade to capture Reed’s giddy highs and floor scraping lows. Be it Reed’s descent during his Sally Can’t Dance period through the punk rock cabaret style of Coney Island Baby, the sobering shots of Growing Up In Public and all points in between, Rock has been there every step of the way to document Reed’s navigation through the 70s hi-octane excesses.

Reed and Rock have re-united to bring together the very best photographs from this period and house them in a single volume, the sumptuously packaged book Transformer. Weighing in at almost 200 pages, Transformer is an incredible document of a time when both rock & roll and rock photography were forging a trail for future generations to follow. Be it in the studio, stage or hotel rooms, Rock’s eye and camera offer an unflinching study of one of rock’s most singular and truly original innovators.

Now aged 71 and recovering from a life-saving liver transplant operation, Reed cuts a frail figure. Though his movements and speech are slow, his mind is as razor sharp as ever and the interaction between him and Rock is touching. With a just a limited amount of time available, The Quietus asks the pair if they view Rock’s work as that of a chronicler or an enhancer of imagery.

Reed’s eyes begin to sparkle and his lips move in an upward direction as he says, "You’re the first person to have asked that and it’s such an obvious question to ask.”

Turning to Rock he drawls, "What do you think?” Rock shrugs his shoulders and replies, "I’ve never really thought about it really."

Oh come on…

"No, I haven’t. It’s just what I do.”

Reed takes up the slack. "It definitely wasn’t enhancement because the image was already there. What Mick did was to be there and capture the moments as they happened and I think he did a really wonderful job. You see, the thing is, he’s really a guitar player but he uses a camera.”

"Ah, but he was an extraordinary subject,” offers Rock to which Reed adds, "And he’s a great photographer."

The affection between the pair is palpable and it’s difficult to disagree with Reed’s assessment that Rock is a guitar player with a camera. Tall with shoulder length hair and dressed in denim, Mick Rock really does possess the air of a rock & roll star.

It’s probably for this reason that Rock captures the very essence of stardom from performance through to the various guises that Reed adopted throughout the 70s. The Quietus wonders if these looks were a reflection of the music that was being made or the personality making it? Rock shakes his head as he points out, "It wasn’t the personality; it was a persona.”

For Reed, Rock’s contributions to enhancing the perception of this persona was part of a wider package: "The look and the persona were very much there to serve the music. What you’re talking about is the complete package – the words, the music and the look."

But what’s apparent throughout the Transformer book is just how different Reed looks from whatever else was happening in the rock universe at the time. One shot that perfectly encapsulates Reed’s difference is his very first appearance in the UK when he joined David Bowie at the Royal Festival Hall in 1972. There’s Ziggy, dressed in white, his hair a flaming red and dressed in a gleaming white jumpsuit while next to him is Reed dressed in his customary black. His outfit may be covered in rhinestones but his monochromatic image is in stark contrast to Bowie’s.

"I was doing was pretty much what I’ve always done,” states Reed when asked if the idea was to present a darker, more adult alternative to the glam of Ziggy Stardust.

"I know what I like be it leather jackets, jeans, distressed boots or whatever,” he continues. "But I guess that it did look different from the others. But you have to remember is that I was a product of Andy Warhol’s Factory. All I did was sit there and observe these incredibly talented and creative people who were continually making art and it was impossible not to be affected by that.”

Surely Reed is being modest here?

"Not at all; you look at Andy – somebody who created himself,” Reed counters. "You know, there he was as a balding commercial artist who took himself off to God knows where and he re-invented himself as this guy in a leather jacket and a wig. And I asked him about the wig because I thought it made him look older and he said, ‘Well, that’s fine because when I do get older it’ll perfect.’”

The Quietus suggests that this all sounds like the Robert Johnson legend – by all counts an average guitar player at the start of his career, he vanished for a year and returned a virtuoso after allegedly selling his soul the devil.

"Oh, you know that story? I wish I could tell you it was like that for me,” sighs Reed.

"You know, that I heard a voice at midnight say [adopts spooky voice], ‘Lou… Lou… this is what you’ll be doing for the rest of your life.’ No, it’s my kick, it’s what I love doing in the same way that your kick is to be here and talk with us about this book and then go and write about it. But it was Angie [Bowie] who gave me that rhinestone jacket and those velvet pants but really it was just a more glamorous version of what I was already wearing."

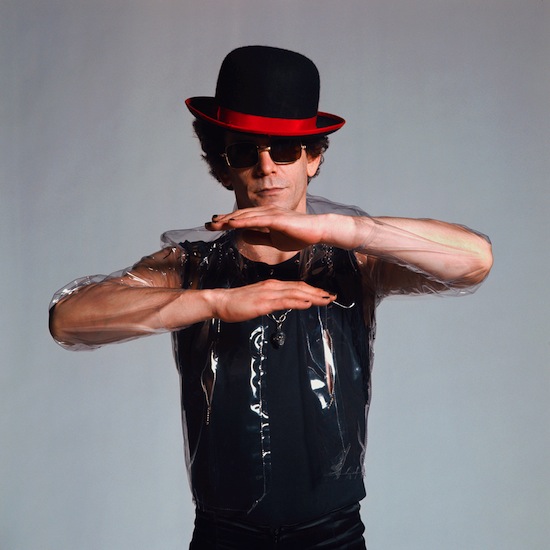

Indeed, looking at Rock’s shots of Reed around Coney Island Baby, it becomes evident that Reed’s preferred black clothing is still very much in place but here he’s getting very much into the fashion that came to dominate the punk era in the UK.

He’s there in a red-tipped bowler hat, dark sunglasses, a t-shirt that unzips to reveal his nipple, fingerless gloves that show off his painted nails, black jeans and Cuban heels all topped off with a clear PVC jacket. Redolent of an infernal version of Liza Minnelli’s Sally Bowles in Cabaret, this is a look that Reed insists that he put together himself.

"There was no stylist there,” confirms Rock. "These were clothes that Lou had brought with him."

"These were clothes and fashions that interested me at the time,” says Reed. "It’s funny; I now see women doing the things that I was doing then, like painting patterns on their finger nails or toe nails and that really does make me laugh.

"But yes, it was punk rock in the way that it should be; to be adventurous, to be creative and to offer something different. The problem is that no one is really making great art any more. The whole point of what I was trying to do was to smash through things. The music should come crashing out of your speakers and grab you and the lyrics should challenge whatever pre-conceived notions that listener has.”

Reed has a point. To look through Transformer is to be transported to a daring time and place of risqué fashions where sexuality was as much a statement as the music he was making; where something as simple as playing with gender roles could both shock and allure in equal measure. But it’s also to be reminded of the power of imagery and how much more striking these photographs look in their more natural environment of pages rather than pixels. Given that we’re now living in a digital age where images are produced and viewed more differently – would that smudged Transformer image have been the same if it had been made yesterday using digital technology? – and music is consumed in an a la carte fashion, could this book be seen as an elegy to a time, place and attitude that will never happen again?

"No, it’s not an elegy,” states Reed. "It’s a chronicle of a time and place that isn’t there any more."

"Or unlikely to happen again,” adds Rock.

"But you’re right,” Reed continues. "We are living in a compressed age where people are perfectly happy to listen to the worst kind of recorded shit imaginable. And who buys albums anymore? People are too busy downloading singles or just single tracks and that isn’t very healthy. I see people watching movies on their phones or iPads and don’t they realise that they’re missing so much?

"But you know what? I’m really proud of this book. This is my life and Mick was there to chronicle it. This isn’t a coffee table book. You wouldn’t put a bowl of fruit on it."

How about a banana?

For a moment, Reed fixes The Quietus with a stare before breaking into laughter.

"Hey, this guy is fast!” Reed tells Rock.

"Maybe we should punish him?” the photographer replies.

Reed shakes his head while still laughing, "No. He’d probably enjoy it.”

I probably would, too. But only if the PVC and the make-up came out again.

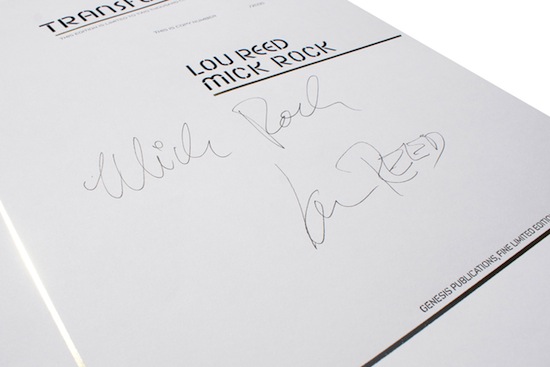

Each of the 2,000 numbered copies in the limited edition has been signed by both Mick Rock and Lou Reed and you can purchase them here