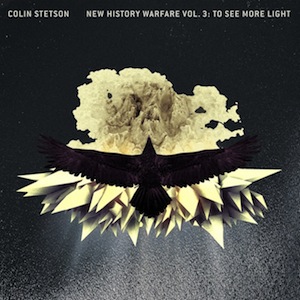

Sometimes, the search for decent music can echo the trials of a mud-flecked truffle hog. Snout-probing through fields of dung-laden musical dirt, so uninspiring that pouring boiled pigswill down your ears is preferable to the offal at hand (or trotter). When did music suddenly stink like the matted hair of a gong farmer? Snuffling out a premium-quality album is such a revelation it can invigorate even the most curmudgeonly of listeners. The most exquisite truffle found so far this year is Colin Stetson’s New History Warfare Vol. 3: To See More Light – a solo bass saxophone record that is so alien-sounding, there are only two logical explanations for its existence: Stetson is a newly-evolved species (that I shall call Homo saxaphonus) with larger lungs and even larger cheeks to rival the storage skills of a hamster, or secondly, he used to reside in Jabba’s Palace busting out solos in The Max Rebo Band alongside Sy Snootles and Droopy McCool.

To See More Light concludes his New History Warfare trilogy, which began in 2008. It’s possible that Colin Stetson is a name already nestled in your record collection, whether through his Bon Iver membership, or collaborating with Arcade Fire, TV On The Radio and even gravel-glands himself, Tom Waits. But his remarkable solo work has totally eclipsed the flare of these heavyweights with a series of brutalist yet ambitious and exhilarating records, the third being no exception. He is an altogether different, Liturgy-loving, sax-destroying manbeast of burden. This is no Kenny G dentist chair nightmare. Imagine a wake ceremony with Juan Atkins on the decks, Stephen O’Malley getting down to the Macarena, Krallice in a conga line and Steve Reich just hanging out, enjoying a mini scotch egg.

The multiphonics emerging simultaneously from this one man band are extraordinary. For starters, rhythmic tiptapping on the foghorn’s valves generates a percussive backbone. Sandpaper bass lines and metallic melodies blossom through overblows and cheek-huffpuffing. Finally, on top of everything else, Stetson also sings directly into the reed. First heard on the hugely impressive ‘Hunted’, it hits like a gushing geyser to the ears, and out-Framptons Peter Frampton’s ‘singing guitar’, giving his sax a raw voice swelling with sadness and fragility. Justin Vernon makes several appearances, most outstandingly on ‘Brute’, in which he sprinkles Stetson’s techno chainsaw-massacred melody with an unexpected bark that sounds akin to Jens Kidman of Meshuggah (who Stetson enjoys running to). Vernon’s normal choiry-manchild voice is present on other tracks of course, but Stetson is best left to shine alone. Case in point – the beautiful ‘Among The Sef’, a swirling tornado of valve-drum gallops and flowing arpeggios that surge like blackened blood through a body. The title track best exhibits his inhuman extended technique skillz (that I’m assuming he developed on Tatooine): fifteen powerful minutes of sax-sludge, thunderous ‘drums’ and lyricless reed-singing at its most woeful, channelling a diplodocus insane with grief after witnessing the slaughter of its family.

Astonishingly, these abyss-sized and multi-layered soundscapes were recorded live in single takes, with no loop pedals or gadgetry in sight. A smattering of microphones dotted in and away from the instrument, and one around his throat dog-collar style, were carefully placed to showcase each unique timbre and texture. He’s also fooled his own respiratory system into breathing out through the nose and into the nose at the same time as the mouth, which exerts a punishing amount of pressure onto the lungs and brain. Think about that for a second – it’s not unlike re-training your sphincter to urinate as well as crapola. Circular breathing is in no way new (and has been explored in various ways by Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Evan Parker and the bonkers bells of Borbetomagus, to name but a few) but Stetson has successfully pushed it in a direction of accessibility and warmth, like a big avant-garde apple crumble.

Mortality resonates throughout this record, perfectly capturing the absolute upsidedownness and emotional shitstorm that death is. And yet, amongst its lingering sorrow, an uplifting fistpump nonetheless emanates and, in turn, Stetson has composed eleven faultless funeral songs (any of which should replace my current choice of R Kelly’s ‘Bump N’ Grind’). It’s testament to his astonishing proficiency as a player and deconstruction of the instrument that Stetson has remoulded ‘the sax solo’ – intrinsically linked with ‘Baker Street’ and elevator smegma – into something completely new, like an Enola Gay blow to the neocortex. And at the very least, it thankfully halts wild bore syndrome from setting in.